Books

Book Stack

Recommended summer reading from Ursula’s editors and contributors

Cover of Lili Is Crying (New York: New Directions, 2025)

Cover of John Gregory Dunne, Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season (New York: McNally Editions, 2025)

Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season by John Gregory Dunne (McNally Editions)

The theme of Las Vegas as a Lourdes for the contemporary condition has been around practically since the first casinos opened on the Strip. As Hunter S. Thompson wrote: “Every now and then when your life gets complicated and the weasels start closing in, the only cure is to load up on heinous chemicals and then drive like a bastard from Hollywood to Las Vegas.” John Gregory Dunne’s rollicking paean to Sin City, first published in 1974 and long out of print, inevitably reads as a kind of rejoinder to Play It As It Lays, published by Joan Didion, his wife, four years earlier. Both novels feature protagonists in the throes of nervous breakdowns. Both are set amid unmoored Western sprawl. Both concern a character’s divorce—in Dunne’s case, a darkly comic attempt to stave off divorce; in Didion’s, finalized. How much of each book spoke to the couple’s actual marriage? Part of the joy in revisiting Dunne’s picaresque is the speculation. “What you have read,” he says, “is a myelogram of six months of my life. I can offer no guarantee that everything you read actually happened, only that insofar as it was perceived by my fractured sensors it was true.”

—Randy Kennedy

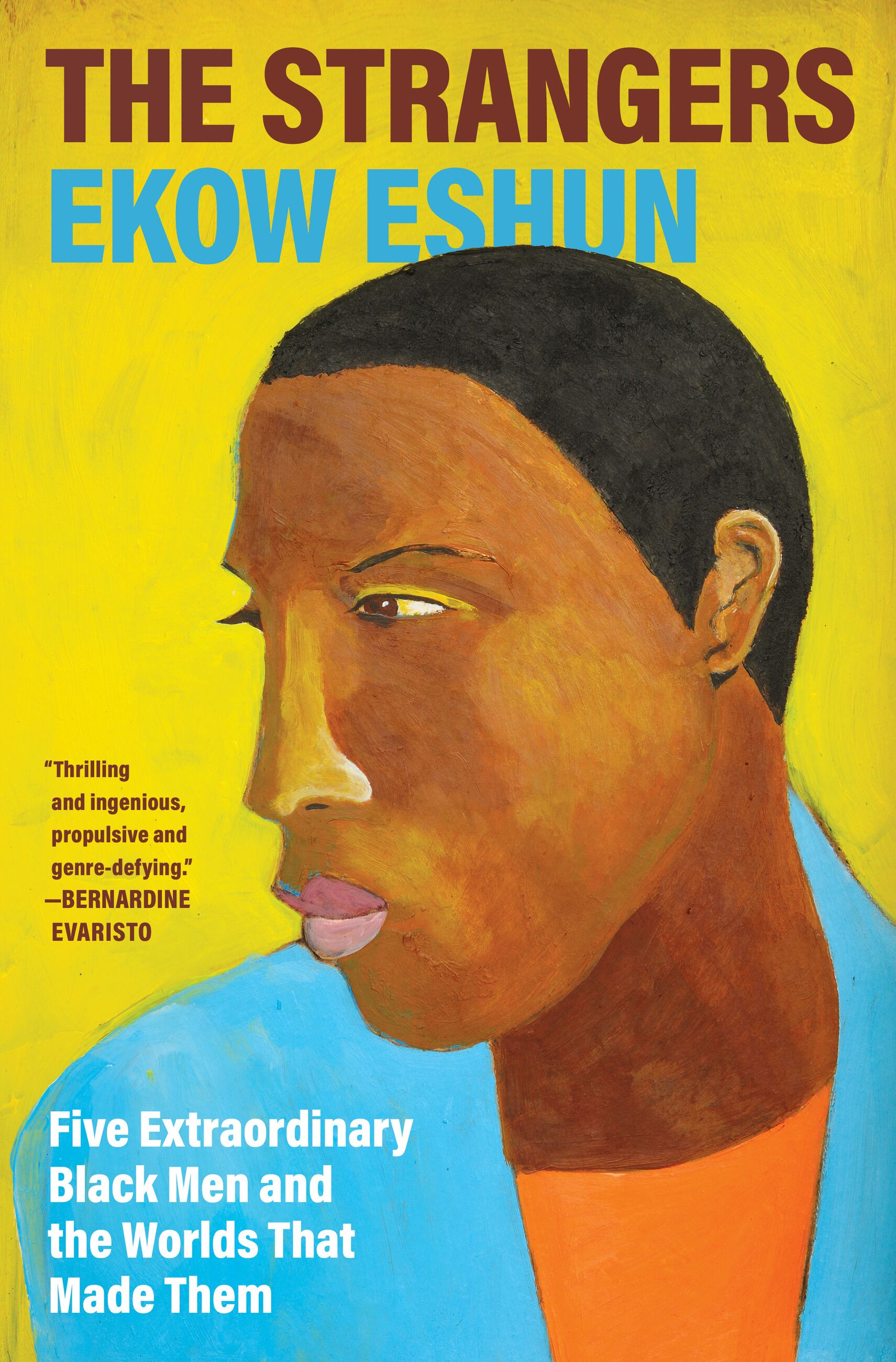

Cover of Ekow Eshun, The Strangers: Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds That Made Them (New York: HarperCollins – US release, 2025)

The Strangers: Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds That Made Them by Ekow Eshun (HarperCollins – US release)

In The Strangers, Ekow Eshun turns away from conventional biography toward something looser and more imaginative, akin to portraiture in painting. Taking as his subjects five Black men who moved through life with extraordinary presence and a deep sense of dislocation—among them, the 19th-century Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge and the English footballer Justin Fashanu—Eshun sketches lives shaped by brilliance and an unyielding desire to be seen.

The book is genre-defying, part history, part fiction, part memoir. Eshun, born in London to Ghanaian parents, threads his own experiences of racial estrangement into his subjects’ stories. What continuously binds these men together is the solitude of being singular in a world that insists on sameness. Eshun doesn’t attempt to resolve this tension. Instead, he leans into the gaps—the silences in the archive, the unknowable inner lives—and fills them with empathic and inventive insights.

The result is more than a ledger of recovered histories. It offers a new blueprint of how such life stories can be meaningfully told. In navigating the blurs of fact and fiction, Eshun finds his truth.

—Alexandra Vargo

Cover of Lili Is Crying (New York: New Directions, 2025)

Lili Is Crying by Hélène Bessette, translated by Kate Briggs (New Directions)

Hélène Bessette. I say the name aloud, as if the words are new. Have you heard of Hélène Bessette? I ask around, to be sure. The words are new. The work is like this, a revelation. Its effect reminded me of something a painter once told me when I asked if he’d read something good lately: If a book was good, he’d stop reading. Start painting.

Lili Is Crying has that kind of energy, like a baton. “Living literature,” as described by Marguerite Duras, it is partly a kind of theater—a dialogue between a mother and daughter and others who get in the way—and also a poem and novel. Naturally slipping into a point of view in one sentence and out the other, at times it even speaks for itself (“The novel is taking its leave” / “The novel is over, but we—we’re not dead”).

While her editor, Raymond Queneau, a founder of the experimental writing group Oulipo, was alive, Bessette published thirteen novels. When he died in 1976, she was left without support and, in time, forgotten; only recently has her work been found again, and never before published in English. Specks of Marie Redonnet’s Hotel Splendid, perhaps, but really not like other things. I’m telling everyone I know!

—Jana Horn

Cover of Parable of the Sower (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2019)

Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler (Grand Central Publishing)

Octavia Butler wrote Parable of the Sower more than thirty years ago, but it is still eerily resonant, reminding us of the importance of language and how the personal is always political.

The book, which I’ve been reading as research for my current exhibition at Hauser & Wirth London, takes up a somehow-familiar scene of life in the aftermath of apocalypse—a world where wealth inequality, corporate greed and climate change have run rampant.

The story is seen through the eyes of Lauren, a hyper-empathetic young woman who is forced to evacuate her Los Angeles home after fire destroys her community. Along the way, Lauren spreads word to new comrades about "Earthseed," a religion she has developed on her own. The novel is an inspiring look at faith and the importance of community—for survival and rising above adversity.

—Michaela Yearwood-Dan

Cover of Arshile Gorky: New York City, edited by Ben Eastham (Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 2025)

Arshile Gorky: New York City, edited by Ben Eastham (Hauser & Wirth Publishers)

In a metropolis defined by change, Arshile Gorky found his match. Marking the centenary of Gorky’s arrival in New York, this volume traces contours of formation— both parallel and intersecting—of an artist and his place.

Through various lenses, the newly commissioned essays in the book expand the bounds of Gorky scholarship, suggesting that his notable ability to confound categorization made him the quintessential New Yorker. He performed masquerade as a mode of self-determination: borrowing, adopting, not assimilating but subsuming, as city- dwellers are wont to do. As essayist Adam Gopnik observes: “His art is busy, busy as New York is busy, busy as his mind was busy.”

The alternating tempo of images—of better- and lesser-known paintings, works on paper and realized and unrealized murals by the artist—allows us to see a symbiosis evolve between Gorky and his city. Iconic cityscapes by Berenice Abbott (who arrived in New York five years after Gorky) are interspersed with archival imagery and photos of the artist in his studio and on the street, showing his progress in parallel with that of his

surroundings.

—Jessica Eisenthal

Cover of William Kentridge: Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot (Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 2025)

William Kentridge: Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot, edited by Karen Marta (Hauser & Wirth Publishers)

In Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot, William Kentridge compresses his nine-part film of the same title into a still-gargantuan image and text meditation on the role of the artist’s studio. Created during the pandemic as a dialogue between Kentridge and his doubles, the book is about what happens when an isolated self is left to multiply across canvases, blackboards and notebooks. The question, says Kentridge, is whether the fragments “eventually add up to an image we can make sense of.”

The studio is a space of accretion, free association and roaming. As time trudges on and restrictions lift, assistants and collaborators begin coming back into the fold, ending Kentridge’s enforced solitude. Yet the query remains the same: how to mediate between inside and out, between the studio, where everything is permitted, and the gallery, where finitude is precisely the point? The hybrid form of Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot is one possible answer to the impossible predicament of the artist— make something of yourself and send it out into the world. Then do it again and again.

—Canada Choate

Cover of Pat Steir: Paintings 2018–2025, text by Colm Tóibín (Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 2025)

Pat Steir: Paintings 2018–2025, text by Colm Tóibín (Hauser & Wirth Publishers)

Speaking with Pat Steir at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden on the occasion of her 2019 exhibition “Color Wheel,” curator Evelyn Hankins astutely summarized the basis of Steir’s momentous contributions to the history of painting: Painting can be a gestural practice, and gestural painting can also be a conceptual practice. For more than forty years, this notion has guided Steir’s working methods. In Pat Steir: Paintings 2018-2025, the past eight years of her rigorous practice are on display in full, glorious detail.

The monograph features a meditative essay by author Colm Tóibín and an interview with Hankins published in print for the first time. The reproduced works, carefully sequenced, allow us to see the ways in which Steir has built and expanded upon her signature method of dripping, pouring and splashing paint, and her singular understanding of color. In its rhythm and pacing, this volume also reflects Steir’s skill as a book designer, her close attention to detail and her facility with the page.

As we learn from her conversation with Hankins, Steir models her studio discipline after that of her friend Agnes Martin. “She made work the way the birds make music,” Steir explains. “She just worked every day. Even at the end of her life, she went to the studio.”

—Alexis Lowry

–

"Michaela Yearwood-Dan: No Time For Despair” remains on view at Hauser & Wirth London through August 2.

Book covers courtesy publishers.