Essays

We Have to Imagine Something Else

Site-specific art therapy: The story of Hospital Rooms

By Charlotte Jansen

Miranda Forrester, Rooted, 2024. Sandwell CAMHS in West Bromwich © Hospital Rooms. Photo: Patrick Dandy

The 19th-century French psychiatrist Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol was an early pioneer of the institutional model of care for psychiatric patients. In 1801, he established a private asylum, championing the idea that the architecture of the therapeutic space should work symbiotically with treatment. In the mid-1800s, the American psychiatrist Thomas Story Kirkbride pursued a similar approach with the construction of seventy-three psychiatric hospitals across the United States under the Kirkbride Plan. Built with high ceilings and large windows, the spaces were to be “tastefully ornamented” and comfortably furnished. Design was considered an integral part of psychiatric care.

When psychiatric institutions were gradually taken over by the state across Europe and the US beginning in the mid-19th century, the ambitions of Esquirol, Kirkbride and others to revolutionize the design of hospitals hit a stumbling block— budget cuts were imposed, and design was no longer a priority. Private asylums, once sites of radically progressive ideas about care, became sources of fear in the collective imagination.

In London, some two centuries later, artist Tim A Shaw was working as a freelance art technician when he met Niamh White, a Goldsmiths graduate working at the front desk for Hauser & Wirth. The two became a couple and produced exhibitions and projects together, for a decade running the Dentons Art Prize for emerging artists. Then, one day in 2016, they received a life-changing phone call: A close friend was in the hospital, having attempted to take her own life.

“We hadn’t been to an inpatient mental health unit before,” Shaw recalls. “It was a shocking experience, seeing someone we loved in a space like that . . . The whiteness, the starkness, the sounds, the smells. Every sensory experience felt aggressive and reflected back a lot of the negative things this person thought about themselves.”

Chantal Joffe, Venice Window 1 and Venice Window 2, 2023. Carbis Ward, Longreach House in Cornwall © Hospital Rooms. Photo: Oliver Udy

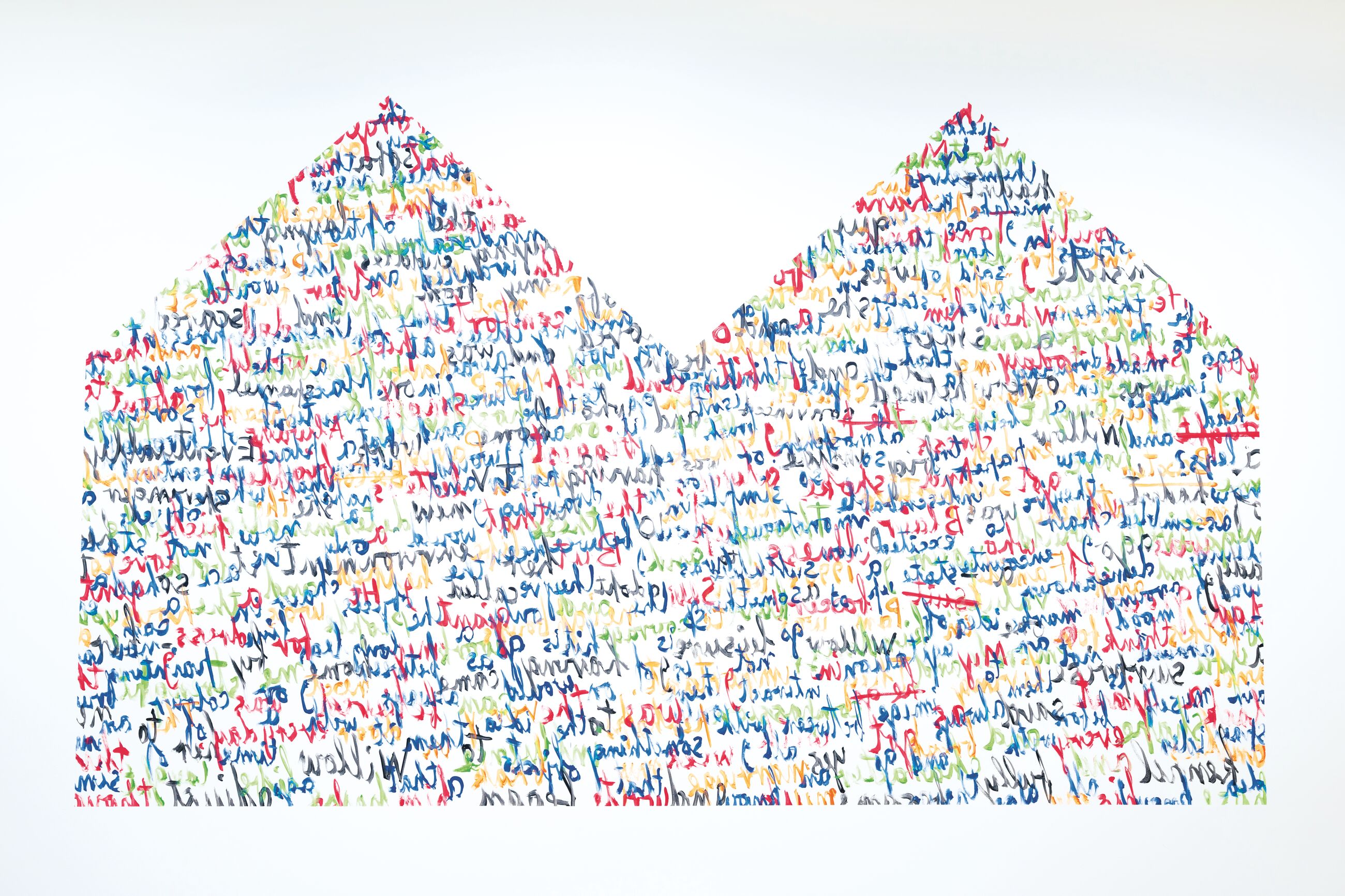

Christian Marclay, Untitled, 2024. Sandwell CAMHS in West Bromwich © Hospital Rooms. Photo: Patrick Dandy

“We hadn’t been to an inpatient mental health unit before. It was a shocking experience, seeing someone we loved in a space like that.”—Tim A Shaw

The very night of their visit, Shaw and White devised a plan to try to fill such spaces with the kind of art one might find in a museum, bringing color and beauty from the outside to the inside of the locked doors. “We thought, ‘There has to be another way. This can’t be the only way these environments can be. We have to imagine something else,’” White told me in a recent interview, with as much passion as she felt on that day almost a decade ago. “We were driven by anger, in many ways, that they could get away with holding people in spaces like that. In some reports, those spaces are cited as retraumatizing people.”

White and Shaw shared a vision not simply to enliven the spaces with color and design but to bring the highest-quality artwork into underfunded and neglected hospitals. In the beginning, they had little idea how difficult their mission would be. They began by contacting National Health Service (NHS) hospitals about organizing an exhibition.

“It quickly became apparent that what we had seen wasn’t an isolated incident,” White says, from Hospital Rooms headquarters in Bow, East London. “This was a well-documented, national problem.” Shaw adds: “We hadn’t quite appreciated how difficult it would be. Almost anything you want to bring in is contraband.”

It was a battle to get even a first project off the ground. NHS psychiatric hospitals conform to a strict color palette and uniform architecture. Often overworked and understaffed, their teams had little time to consider design, with health and safety rules adding further barriers.

Sovay Berriman, MESKLA | Rag Porth / For Cove (Liwyow a Gernow), 2023. Cove Ward, Longreach House in Cornwall © Hospital Rooms. Photo: Oliver Udy

Then came a breakthrough. A medical director at the Phoenix Unit at Springfield University Hospital in Tooting—a rehabilitation ward for patients with schizophrenia—agreed to give the project a chance. Shaw and White brought in artists Nick Knight, Gavin Turk and Assemble, the Turner Prize-winning collective, to create new site-specific works for the spaces used by eighteen patients. “It wasn’t immediate,” White says, “but the tide slowly started to turn. NHS staff began approaching us and saying, ‘Our ward is also terrible. Can you please come and help us?’”

White and Shaw’s work in the art world shaped the way they approached Hospital Rooms, combining creative ambition with a practical understanding of how to realize complex projects. Their mutual and longstanding connection with Hauser & Wirth proved especially significant. In 2022, Hospital Rooms entered into a three-year fundraising partnership with the gallery, which pledged to raise £1 million in support of the charity’s expansion. The partnership has been transformational, turning what began as a grassroots initiative into a nationally recognized model for creative mental health care, now supported by a staff of twenty.

The collaboration began with a series of exhibitions at the gallery’s London space. The first, “Like There Is Hope and I Can Dream of Another World,” opened in 2022 and reimagined the gallery as an NHS ward, with beds, furniture and immersive works created in partnership with artists and patients. A second exhibition, “Holding Space,” followed in 2023. Works from both shows were sold through charity auctions, and by 2024, the fundraising target had been surpassed.

Fabian Peake, The Forest, 2024. Kester Family Room, Hellesdon Hospital in Norwich © Hospital Rooms. Photo: Damian Griffiths

Ben Sanderson, The Blue Between Two Greens, 2023. Cove Ward, Longreach House in Cornwall © Hospital Rooms. Photo: Oliver Udy

“It wasn’t immediate, but the tide slowly started to turn. NHS staff started to approach us and say, ‘Our ward is also terrible. Can you please come and help us?’”—Niamh White

The raised funds enabled the launch of Hospital Rooms’ Digital Art School, a national program delivering monthly artist-led workshops and bespoke art materials to mental health hospitals across England. In 2024, all fifty-eight NHS Mental Health Trusts—the public bodies responsible for inpatient care—joined the initiative. Each Trust now receives custom packages, designed with clinical safety in mind, along with regular creative sessions for patients. Originally piloted during the Covid-19 pandemic, the current program has become central to Hospital Rooms’ mission, offering consistent access to high-quality artistic engagement in settings where such experiences have been historically rare.

A few weeks after we spoke, Shaw was awarded an MBE for Services to the Arts, a public acknowledgment of the organization’s outstanding contributions. And yet, Shaw says, smiling tersely: “We still get told, ‘There’s a reason why the walls are magnolia.’”

Hospital Rooms is not only socially conscious but also a deep collaborative effort between artists, NHS staff and patients, known as service users. After conducting research to determine which artists are the best fit for each site, the charity invites the artists to spend extensive time at the facilities and run workshops with service users. Then the artists return to their studios to create work informed by their experiences. Even when taking into account the strict rules about the kinds of materials and images that can be brought into a mental-health ward, Shaw says, the collaborative process creates something “exceptional and extraordinary for a space that usually has nothing.”

Phillippa Clayden, The Patient Man, 2024. Bowman Ward, Bodmin Community Hospital in Cornwall © Hospital Rooms. Photo: Oliver Udy

Dolly Sen, Daisy Ways, 2025. Hellesdon Hospital in Norwich © Hospital Rooms. Photo: Damian Griffiths

“Why shouldn’t we have world-class art in spaces where people are trying to recover?”—Katharine Lazenby

“It’s chilling when you see the list of things you can’t use,” the artist Chantal Joffe tells me on the phone. “It has to be wipeable, splashproof, anti-ligature.” Her contribution to the Carbis Ward at Longreach House, an acute psychiatric ward in Cornwall, is a serene diptych painting that offers patients a view of two vistas in Venice, where she has spent time working.

“I thought if I could provide the view to a place you could imagine going, it might offer some comfort,” she says. “When I went to install the paintings in the ward, a man who was clearly in distress came up to me and said: ‘Is it Venice?’ He was pleased to have identified the place. I thought, ‘If one person could be taken away from the thinking they do when they’re distressed, even for a minute, just by the act of looking—that would be amazing.’”

The workshops also left an impression on Joffe, with their emphasis that little things, in dire times, mean a lot. “They serve tea in china cups,” she says. “They bring in chocolate and biscuits and flowers. It creates an atmosphere where people are treated like they are valuable human beings. Everyone should feel they’re worthy of beauty.”

Many of the artists Hospital Rooms have worked with are art-world celebrities, but, Shaw says, “when you bring them into a mental health unit, they become human. There’s a kindness and generosity.” (And there’s no fanfare—lunch might be “some bread with hummus on the couch.”)

–

Charlotte Jansen is a British Sri Lankan author, journalist and critic. She writes about art and photography for The Guardian, The New York Times and British Vogue. She is the author of Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze (2017) and Photography Now (2021).