Elisabeth Frink: Transformation

Elisabeth Frink, 'Goggle Head I', 1969 © Frink Estate. Photo: Dominic Brown

Elisabeth Frink: Transformation

This resource has been produced to accompany the exhibition, ‘Elisabeth Frink, Transformation’ at Hauser & Wirth Somerset. This publication is designed for teachers and students, to be used alongside their visit to the exhibition. It provides an introduction to the artist Elisabeth Frink, identifies the key themes of her work, methods of practise and makes reference to some of the contexts in which her practice can be understood. It offers activities that can be carried out during a visit to the gallery and topics for discussion and additional research. The exhibition ‘Transformation’ focuses on a selection of Frink’s distinctive bronzes produced in the 1950s and 1960s as well as works from the 1980s, alongside a series of drawings that highlight the artist’s skill as a draughtsman. The works are displayed in the Rhoades and Bourgeois Galleries. Outside in the Cloisters Courtyard are some of Frink’s most important sculptures from her later life, including the celebrated Riace figures.

About Elisabeth Frink

Elisabeth Frink was born in 1930 in Thurlow, Suffolk. Her father was an officer in the 7th Dragoon Guards and the Indian Army cavalry regiment, Skinner's Horse. She was nine years old when the Second World War broke out and living near an airbase, it had a direct impact on her lifestyle. Growing up in the countryside meant that Elisabeth, or Lis as she was known, developed a love and fascination with the outdoors.She was taught to ride and also to shoot for food. In order to escape the dangers of living so near to the airfield, she was moved with her brother to Exmouth in Devon. Here they continued their education at a local school and Lis attended drawing lessons at a nearby convent. However, it was a trip to Italy to visit her father in Trieste, when she was a teenager, which included a visit to Venice, that really inspired her. It was here that she was so excited by what she saw that she declared her desire to attend art school.

She went on to study at Guildford and The Chelsea School of Art between 1947 and 1953, where Bernard Meadows and Willi Soukop were her tutors. In adult life, Frink herself taught at Chelsea (1953 – 60) and St Martin's School of Art (1955 – 57). Frink’s early work, in particular her birds with their threatening beaks, can be seen within the Surrealist-influenced English sculpture that was named the Geometry of Fear. These attitudes reflect the styles and trends of her teachers at Chelsea School of Art in the 1950s. Elisabeth moved to France in the late 1960s; she felt that her work was out of fashion in Britain as it was not following either the reworked European modernist sculptural trends coming from America towards assemblage, or pop art. Frink was among those contemporary artists who continued to be fascinated by material and process.

Most significantly her interest in using figurative shapes as a vehicle for expressing humanitarian concerns was very different from the growing use of imagery from popular culture within the pop art movement. Elisabeth Frink was only 22 years old when she achieved her first commercial success. In 1952, she had her first solo exhibition at the Beaux Arts Gallery in London and the Tate Gallery purchased a work entitled 'Bird' (1952). Frink soon became known as one of Britain’s best post-war sculptors and figurative artists; she also worked in drawing, printmaking and produced illustrations. She is especially well known for her public commissions, for example ‘Risen Christ’ in Liverpool Cathedral, installed a week before she sadly died from throat cancer in 1993.

Elisabeth Frink with Birdman c. 1960 © Frink Estate. Photo: John Morley

Frink’s early work is characterised by a rough treatment of very fluid plaster surfaces. From the 1960s onwards she evolved a very different method of working, using plaster in a drier state, developing smoother surfaces upon which she could bring into relief more subtle textures and marks. This was allied to her growing interest in the potential of mass and volume to express inner and outer states of being. Each of her sculptures embodies her creative process and personal impression. She gradually began to introduce carved chisel marks, using them as rhythmic patterns.

At the same time she began to play with colour, first by applying metallic paints and then through using chemicals to create different coloured patinations, see ‘Fish Head’ (1961). The methods she used made familiar subjects such as men, horses or birds become abstract. Her sculptural language addressed her concerns about what it means to be human and our capacity for aggression. For Frink being a woman did not mean that she had to associate her practice solely with the concerns of the feminist movement. In 1980, for example, she exhibited in ‘Women’s Images of Men’ at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London. In 1977 Frink was elected a member of the Royal Academy. Her achievements also earned her a CBE (1969) and in 1982 she was made a Dame of the British Empire.

Elisabeth Frink, ‘Birdman’, 1962. © Frink Estate. Photo: Ken Adlard.

Elisabeth Frink worked as an artist from her early 20s and she produced over 400 sculptures during the course of her career. She made all of the work herself without the help of studio assistants. Frink worked alone mainly because she saw sculpture as such a tactile activity, she needed to feel the creation of her work herself; she also said that she worked quickly and felt that there was not time to get anyone else involved. Elisabeth Frink’s work does not necessarily fit into a specific movement or style. She followed a very individual route to making her work, independent to the styles and fashions in sculpture practised by her contemporaries.

In particular artists such as Anthony Caro and other sculptors known as the New Generation working in the 1960s, who experimented with materials, forms and colours with the shared aim of ridding sculpture of its traditional base. However, influenced by her tutor Bernard Meadows, Frink was acknowledged as being part of the avant-garde, post war school of expressionist British sculpture. This included artists such as Lynn Chadwick and Kenneth Armitage. Elisabeth Frink was an ambitious artist and from the beginning of her career made a commitment to investigating male figures, animals and birds. These subjects have become well known as the themes of her sculptures; her work always expressed the nature of the human condition.

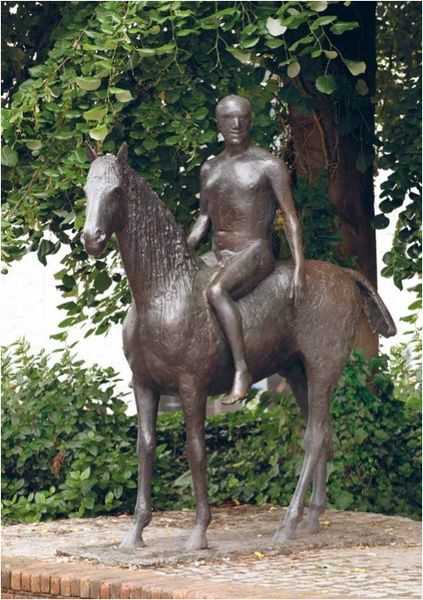

Elisabeth Frink, 'Horse and Rider', 1974 © Frink Estate. Courtesy of Beaux Arts

Public Sculpture

Frink’s figurative sculptures immediately caught the attention of the commissioners involved in rebuilding Britain’s cities after the war, and the building of New Towns. She was only in her twenties when she received her first commission. Her capacity to produce traditional sculptures, that at the same time captured the modernisation of the twentieth century made her work popular for civic and religious commissions. In the South West you can see ‘Walking Madonna’ (1981) at Salisbury Cathedral; ‘Dorset Martyrs’ (1986), in Dorchester; and ‘Horse and Rider’ (1974) in Winchester as well as in Dover Street, London.

Process and Materials

Whilst Rodin exerted a powerful influence on those 20th century figurative sculptors who followed the classical tradition, Frink rejected his handling of material and tried to keep her sculptures wild or natural. She modelled in plaster rather than using clay, and sought to represent a universal humanity, rather than individual personalities. Elisabeth Frink’s preferred working method was similar to Giacometti’s technique of building up directly onto plaster on an armature. This involved using metal rods and wire, then wet plaster with bits of wood and paper and studio debris incorporated into the mass, then working back into the dry form. She often used an axe, then chisels and files.

This method of working results in very expressive surfaces, they record Frink’s own hand and marks, and the energy that she had to put into this style of making sculpture. She did not want her work to be calculated, or too worked out beforehand. By working so quickly directly into her materials she could keep her work exciting and energetic; it was as if she could bring to life an otherwise inanimate material. Most of her sculptures were made in this way and they were then cast in bronze. However, some of her early sculptures were also made in concrete. Elisabeth Frink, Lynn Chadwick and Barbara Hepworth, all working during the post-war period, are characterised by the exploitation of new, often industrial materials such as plastics and concrete, as well as new techniques in welding and casting. Frink used concrete in particular because it would have been more affordable at this time than bronze.

Elisabeth Frink, 'Birdman', 1960 © Frink Estate. Photo: John Morley

Themes Human Condition

Frink’s interest in animals lay in their relationship to man, believing that all life forms were equal; if mankind could see himself as equal to animals, then it would follow that there could be no injustice between men. She reminds us of our dependence on the natural world, which we are part of and not superior to.

Religion

Elisabeth Frink was raised as a Catholic. As she grew up she moved away from religion but never lost her sense of the spiritual. Her work was anti- intellectual but passionate, and this may help to explain its popularity; it appeals directly to the senses and emotions without being didactic like religious art of the past.

Myths & Shape Shifting (Transformation)

The impact of her experiences of living in the countryside with the backdrop of war as a child influenced Frink’s approach to her work. It led to a life-long preoccupation with conflict, injustice and man’s capacity for brutality. She had an interest in how man expresses complex issues through myths and metaphors, notably in relation to war. She said that she ‘created her own myths’ by which she meant that she didn’t re-present earlier myths but worked within that language and way of thinking.

This was closely allied to modern literary techniques used by writers such as Günter Grass and Latin American writers such as Gabriel García Márquez and Jorge Luis Borges to explore political humanitarian themes, by subverting the normal through the inclusion of mythical elements. Frink’s range of subjects included men, animals and birds, exploring their shapes to convey tension, aggression and vulnerability.

War

Her family home was near an airfield where bombers often returned from the war, sometimes in flames, and she remembered hiding from a machine gun attack from a German fighter plane when she lived in Devon. The countryside influenced both her love of nature but was also a place where she experienced the horrors of war. Frink felt a deep concern for the fragility of the post war period, the looming cold war and ongoing nuclear threat – all atrocities created by the human species. She expressed these feelings through her images of birds. ‘Vulture’ (1952) has an ancient, fossilised quality, hunched over awaiting its prey; it represents many of the artist’s deep held feelings about war and aggression. The warped body and twisted limbs of ‘Dead Hen’ (1957) conjure up images of the concentration camps that Frink must have viewed as a teenager.

Elisabeth Frink, 'Vulture', 1952 © Frink Estate. Photo: Dominic Brown

Subjects Birds

In Frink’s early work, animal forms were given a powerful, often menacing, appearance, such as ‘Bird’ (1952), which, despite its small size, appears intimidating and defiant. Reminiscent of the ravens and crows she saw as a child. The bird theme occupied Frink for many years; ‘Harbinger Bird III’ (1961) is a development from the earlier bird series and is constructed from more slab- like, solid forms reminiscent of armour. The birds adopt more explicit military references in the Standard series – vultures poised atop their perches, representing those who have been honoured in the armed forces for their part in the killing of other men.

The continuing preoccupation with flight and transformation or shape-shifting is apparent in the Birdman series, which begins with the erect ‘Birdman’ (1960), a spindly, helmeted character, standing tall as if preparing to take off. The origin of this series came from Frink’s interest in the 1956 attempt of Frenchman Leo Valentin to fly like a bird, using wooden wings. The image of this bird-like figure in the sky resonated with the artist and drew on her memories of planes tumbling from the sky and most significantly became a metaphor for man’s capacity to feel that they are invulnerable. This corresponded to the time of the testing of nuclear bombs and the growing threat of the cold war.

Elisabeth Frink, 'Bird', 1952 © Frink Estate. Photo: Dominic Brown

Horses

Elisabeth Frink learnt to ride a horse when she was three years old. She spent much of her time as a child enjoying the outdoors and her experience of nature led her to draw animals, often from memory. On the walls of the Rhoades Gallery are a series of works on paper, including ‘Horse’ (1958), like the sculptures they appear with, they are semi-abstract in nature, skull-like and often foreboding. These are not preparatory works for the sculpture but are nonetheless related, see ‘Winged Beast’ (1961), another predatory birdlike figure. As with her sculpture, Frink explored a theme through many drawings, before moving on to a new subject.

Heads

On display in the courtyard are ‘Desert Quartet III’ and ‘Desert Quartet IV’ (1989) from a series of four oversized heads inspired by a visit to the Tunisian desert. On entering the Rhoades gallery, the viewer is met with a series of abstract heads belonging to both man and beast. Frink consistently found inspiration in the head, regarding it as the centre of emotion and the seat of the soul. For example, the semi-abstract head of ‘Soldier’ (1963) guards the space, sentry-like. A trio of heads just beyond, appear brutish and intimidating, the heavy jaw and scarred face of ‘Soldiers Head IV’ (1965) a stark reminder of Frink’s ongoing preoccupation with war and brutality. A pair of killers ‘Assassins II’ (1963) stand opposite, their faces obscured behind armour and masks. Fused together, the pair have lost their individual identities and are forced to take on the role of the assassin. Their spindly legs a reminder that they are sensate beings, vulnerable yet capable of killing in cold blood and responsible for their own actions. Next to them a possible victim, ‘Falling Man’ (1961), tumbles to earth.

Elisabeth Frink, 'Desert Quartet III', 1989 © Frink Estate. Photo: Dominic Brown

Masculinity and the subject of Man

As a child, Frink was competent in riding and shooting, and adored dogs, all of which were considered at the time to be male activities and attributes. It could be said that this fascination with masculinity would become a dominant feature of her art. She used the male form as a vehicle for expressing vulnerability and aggression, in stark contrast to the tradition of the male form as an ideal of beauty or hero. Although not overtly feminist this is also very different from the tradition of the male sculptor’s gaze upon the female form.

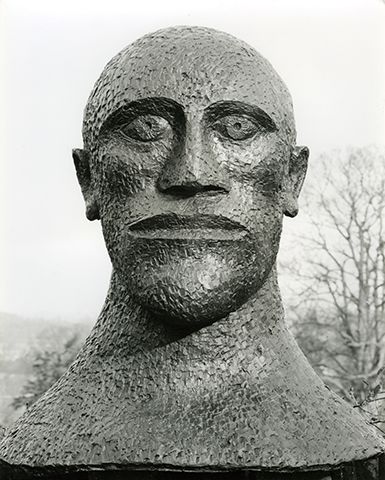

Goggle Heads

In the late 1960s whilst living in France, Frink began work on a series of sinister oversized male busts known as the Goggle Heads, their eyes concealed behind polished goggles. The heads appear smooth and impermeable, representing their strength and lack of humanity, different to artist’s earlier highly textured works. This series was inspired by a prominent figure in the news at that time: General Oufkir, a captain of the French army of Morocco, who allegedly arranged the ‘disappearance’ of left-wing politician Mehdi Ben Barka. Oufkir, who always appeared in dark glasses, was feared by many dissident groups and seen as extraordinarily close to power. Frink’s Goggle Heads show the very worst side of mankind; power hungry, murderous and inhumane.

Elisabeth Frink, 'Goggle Head I', 1969 © Frink Estate. Photo: Dominic Brown

Riace Figures

Visible through the windows of the gallery in the Cloister Courtyard are the menacing figures of the Riace men, inspired by the discovery in 1972 of two full-size ancient Greek bronzes, The Riace Warriors (also referred to as the Riace bronzes or Bronzi di Riace) found under the sea off the coast of Italy. Frink viewed the original Riace Warriors on display in Florence and was struck by their sinister appearance. The introduction of colour and the painted faces can be traced to Frink’s visit to Australia and an interest in aboriginal art.

Elisabeth Frink, 'Riace Warriors', 1986 – 1989 © Frink Estate

Related Artists to Consider

Kenneth Armitage (1916 – 2002)

Kenneth Armitage belonged to the movement known as Geometry of Fear. It was a term coined by the critic Herbert Read in 1952 to describe the work of a group of young British sculptors characterised by tortured, battered or blasted looking human, or sometimes animal figures.1 Like Frink, Armitage made sculpture that was mainly figurative and showed a concern for the human condition.

Anthony Caro (1924 – 2013)

‘Early One Morning’ (1962) is a major example of the kind of sculpture that established Caro as the leading young sculptor of the 1960s. In this work, his arrangement of planes and lines along a horizontal axis gave greater freedom in creating different rhythms and configurations. The work has no fixed visual identity and no single focus of interest. Rather, it unfolds and expands into the spectator’s space, its appearance changing with the viewpoint. The individual elements are unified by the bright red colour and Caro sees the way they cohere, making a sculptural whole, as being like the relationship of notes within a piece of music.

Lynn Chadwick (1914 – 2003)

An early training as an architectural draughtsman together with his practical skills in welding gave him the basis for his individual approach to sculpture. His work was constructed from welded iron rods to form an exoskeleton, which delineates the planes and establishes the stance of the piece. With this unique and singular language he evolved a range of his own archetypal figures and beasts. Throughout a long and distinguished career Chadwick’s work kept a relevance and individuality.

Jacob Epstein (1880 – 1959)

Jacob Epstein made his name as a sculptor of monuments and portraits, and as an occasional painter and illustrator. In his lifetime he championed many of the concepts central to modernist sculpture, including ‘truth to material’, direct carving, and inspiration from so-called primitive art, all of which became central to twentieth-century practice.

Alberto Giacometti (1901 – 1966)

Alberto Giacometti’s work creates a profound experience of figure and space. Focusing on the space immediately surrounding a person or object, his work is at once conceptual and emotional, anonymous and specific, ancient and modern. From 1947 he started to make figures that were very tall and thin.

Barbara Hepworth (1903 – 1975)

Born in Yorkshire and trained at Leeds School of Art and subsequently the Royal College of Art in London, Hepworth left London at the outbreak of the War and established herself in St Ives, Cornwall. This was to be her home for the rest of her life. Many of the simplified, organic, abstract forms and themes found in Hepworth’s work can be linked to the Cornish landscape and coastline, which were a source of inspiration throughout her life.

Hans Josephsohn (1920 – 2012)

Josephsohn’s art is devoted entirely to the human form, the classical theme of sculpture: standing, sitting and recumbent; as full or half figures, bodiless heads or reliefs in which figures are positioned in relation to one another. Formed out of plaster, they are then cast in brass. The artist has said of his figures that ‘they must be enduring in their expression, in their stance’ and his sculpted beings convey an intensity that speaks of stoicism and dignity in the face of suffering. Further reading.

Henry Moore (1898 – 1986)

Henry Moore came to prominence before the 2nd World War through his interest in Surrealism and ‘Truth to Materials’. Moore and Hepworth are seen as being responsible for re-establishing British sculpture through their modern approach to handling material and developing form. Further reading.

Germaine Richier (1902 – 1959)

Germaine Richier was a French artist who also worked with animals and figures. Elisabeth Frink’s technique of building up the sculptural form directly in plaster was a method first employed by artists such as Alberto Giacometti and Germaine Richier in France in the mid-1940s.

Auguste Rodin (1840 – 1917)

Rodin was an extraordinary creative artist and a prolific worker. His discovery of Michelangelo, during a visit to Italy in 1875 - 76, was a decisive moment in his career. Rodin would, in turn, break new ground in sculpture, paving the way for 20th-century art, by introducing methods and techniques that were central to his own artistic aesthetics.

Mark Wallinger (born 1959)

A contemporary artist who represents the human condition is Mark Wallinger, his work describes key events, and situations which compose the essentials of human existence, such as aspiration, conflict, and mortality. Further reading.

References

Suggested Activities

In addition to speaking, the interpretation of art works is enriched by practical activities; educational visits to the gallery often involve creative workshops, particularly drawing.

Drawings

Working in pairs, one person wears a blindfold and their partner guides them into the gallery, chooses a sculpture and starts describing it. Assist the person wearing the blindfold to hold a pencil and to draw from your description. What words can accurately describe what you can see to someone who can’t?

Negative space is the space that surrounds an Just as important as the object itself, negative space helps to define the boundaries of positive and negative space. Look through a viewfinder at one of the sculptures and rather than drawing the sculpture itself, try and draw the space around and in-between it.

Select one of Frink’s sculptures and use pipe cleaners or paper straws to produce a 3D drawing of the shape. Using modelling clay, make a solid sculptural form in the shape of your pipe cleaner or straw 3D

How can a line drawing show different material qualities and emotions? After looking at Frink’s drawings, find a sculpture and make three drawings:

( a ) A drawing that demonstrates the material that the sculpture is made ( b ) A drawing with a line that shows aggression. ( c ) A drawing with a line that demonstrates

Words

1) Choose one of Elisabeth Frink’s sculptures of a bird; how many words can you think of to describe it. Use these words to create an acrostic poem for bird:

B I R D

2) Split into small groups, find a sculpture of your choice, discuss it and in your group select the best five words to describe Then return to the whole group, each small group has to share their five words and the other groups have to work out which sculpture they were looking at.

Elisabeth Frink, 'Harbinger Bird III', 1961 © Frink Estate. Photo: Dominic Brown

Discussion Questions

Key Stage 1 & 2

What is a sculpture?

What things do you usually find made into sculptures?

If you had the opportunity to make a sculpture of an animal, what would you choose?

Key Stage 3

One of the themes of this exhibition is war, how would you make art to address war in the world today?

Animals are often used as metaphors to convey emotion, what animal would you use to represent: anger, fear, peace or reconciliation?

Key Stage 4 and beyond

How would the artworks look in a different space, both inside and outside the gallery?

Do you know of any other artists who create public sculpture? Is there a public sculpture near where you live, what do you feel about it?

Why do you think certain works are displayed in the spaces that they are? E.g. cities, parks, housing estates. How might these create meanings?

Elisabeth Frink, 'Head', 1959 © Frink Estate. Photo: Dominic Brown.

Practical Activity Prompts

Key Stage 1 & 2

Make your own animal or human figure using found objects or by scrunching and folding and twisting newspaper and securing with

Key Stage 3

What animal did you choose as a metaphor for an emotion? Make a sculpture of your chosen

Key Stage 4 and beyond

What is the difference between monuments and sculptures? Collect images as

Sketch or design a monument to celebrate the human

Elisabeth Frink, 'Head', 1967 © Frink Estate. Photo: Dominic Brown

Supplementary Research

Annette Ratusznaik (Ed.), ‘Elisabeth Frink: Catalogue Raisonne of Sculpture 1947-93’, Lund Humphries in association with the Frink Estate and Beaux Arts: London, 2013 Edward Lucie-Smith, ‘Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture Since 1984 and Drawings’, Art Books International: London, 1994 ‘Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture and Drawings 1950-1990’, The National Museum of Women in the Arts: Washington DC, 1990 ‘Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture and Drawings 1952- 1984’, Royal Academy of Arts: London, 1985 Yorkshire Sculpture Park https://www.ysp.co.uk/ Imperial War Museums https://www.iwm.org.uk/

Resources

1 / 10