Henry Moore

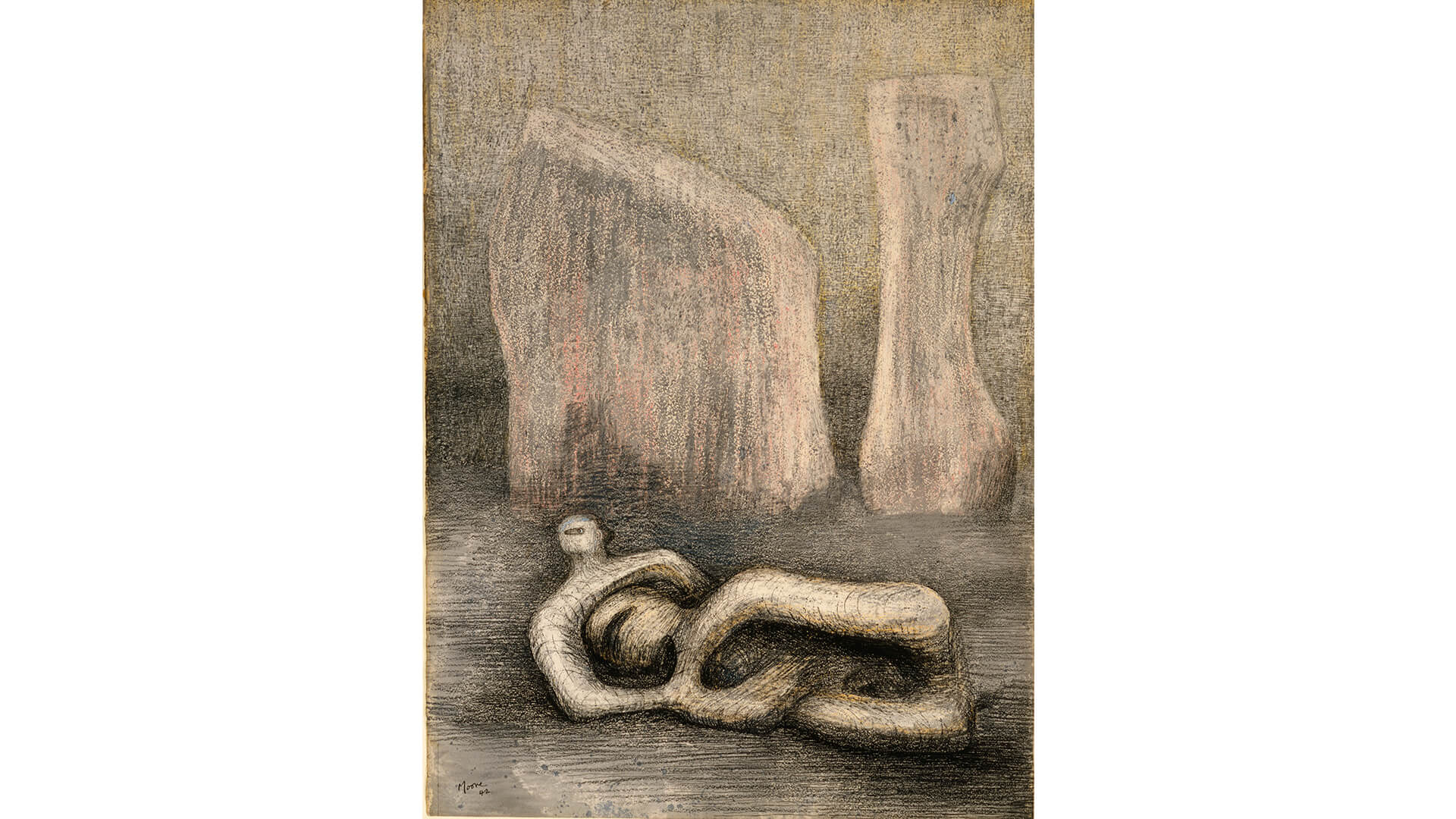

Reclining Figure

Reclining Figure

1945 Terracotta 8.5 x 17 x 7 cm / 3 ⅜ x 6 ¾ x 2 ¾ in

Evoking gestations of the natural world through an elegant intertwining of solids and voids, nested forms, ovoid shapes, and curvatures, Henry Moore’s ‘Reclining Figure’ (1945) exudes a sense of warmth and immediacy that could only manifest through the direct relationship between artist’s hand and clay. Unified here, we find Moore’s signature themes of female form and mother and child, represented in one of his most enduring subjects: the recumbent body, a timeless composition that yielded a lifetime of variations.

Leading up to the Second World War, Moore’s output was almost entirely dedicated to direct carving, primarily working with wood or stone. [Fig. 1] However, with the advent of war came imposed changes to his production. After their London flat was damaged during a bombing in 1940, the artist and his wife Irina relocated to Perry Green, Hertfordshire, where they rented out a farmhouse and ultimately settled, acquiring the property upon which they later erected numerous studios.

[Fig. 1] Reclining Figure, 1945-6, elmwood (LH 263) Photo: Henry Moore Archive

Although his large-scale sculptural practice was stymied during this period, Moore produced numerous drawings, and began experimenting with lead, which he was able to cast domestically, and also made small terracotta maquettes, resulting in ‘Reclining Figure’. Between 1943 and 1945, he generated approximately 28 ‘Family Groups’ and ‘Mother and Child’ works, as well as 14 ‘Reclining Figures’, all rendered in reddish earthenware. [1]

‘I want to be quite free of having to find a ‘reason’ for doing the Reclining Figures, and freer still of having to find a ‘meaning’ for them. The vital thing for an artist is to have a subject that allows to try out all kinds of formal ideas—things that he doesn’t yet know about for certain but wants to experiment with…’—Henry Moore

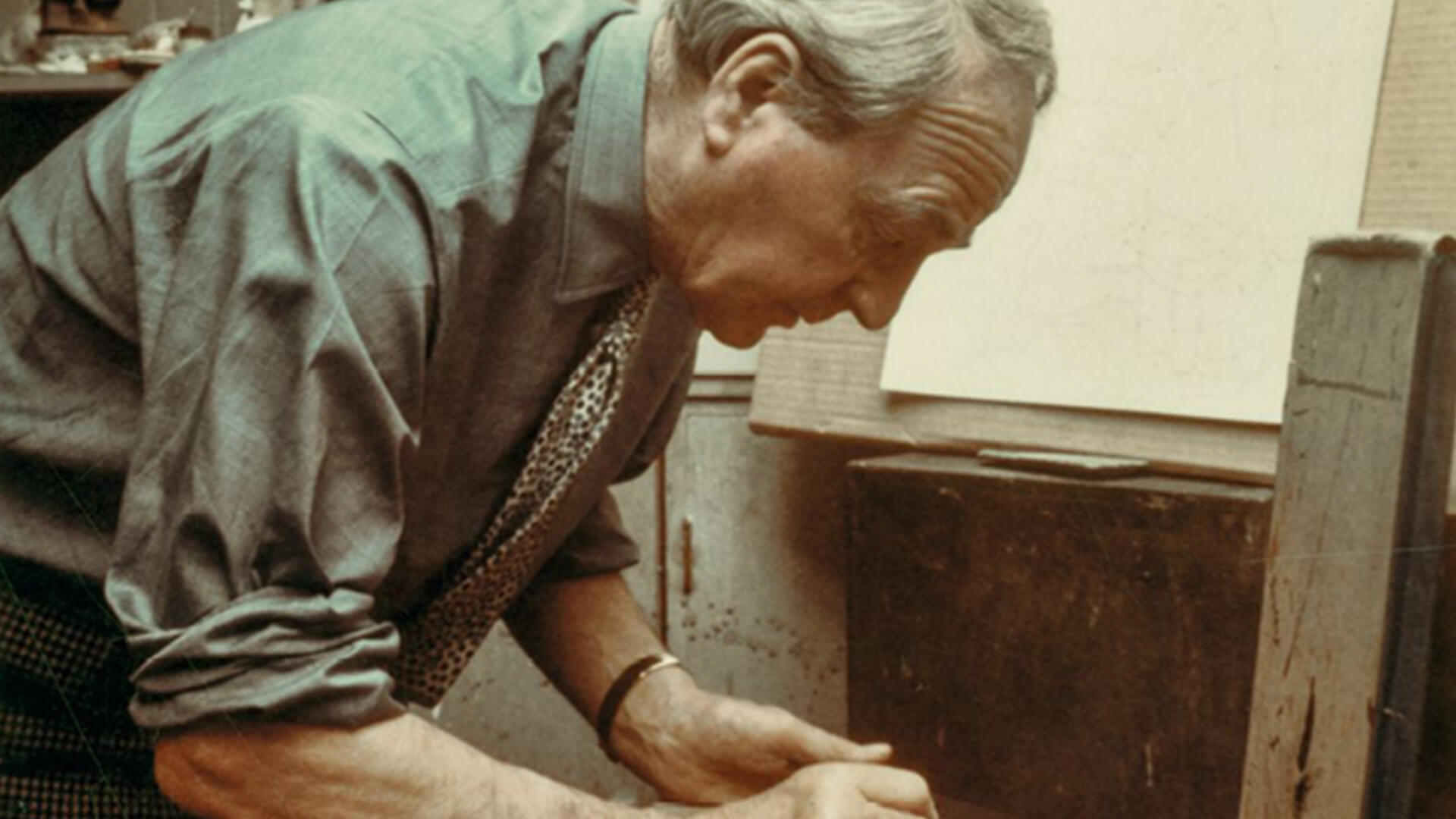

The malleable nature of clay allowed Moore to translate his ideas freely, forming maquettes, as he described: ‘not much bigger than one's hand so that you can turn them around as you shape them and work on them. And you have a complete grasp of their shape from all around the whole time. But all the time that I'm doing the small model it's the big sculpture I intend to do… then it's only carrying out one's original idea in reality.’ [2]

Clearly pleased with the terracotta ‘Reclining Figure’, which initially surfaced in his 1942 drawing ‘Reclining Figure with Pink Rocks’, Moore subsequently cast the work in bronze, leading to the sensuously carved Elmwood version, a monumental rendering created between autumn 1945 and October 1946. [Figs. 2-3] Moore documented the development of the Elmwood version, which was ultimately acquired by the Cranbrook Art Museum, Detroit, and later sold at auction to raise funds—achieving a record price for a sculpture by a living artist. [Fig. 1]

[Fig. 2] Reclining Figure with Pink Rocks, 1942 Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Room of Contemporary Art Fund, 1943 (RCA1943:13) © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Biff Henrich.

This celebrated terracotta version of ‘Reclining Figure’ exemplifies an integral part of his sculptural process. And as his later small-scale maquette explorations of the 1950s and 1960s were made of plaster, his surviving terracotta examples are all the more exceptional. Testament the importance of this work, nearly three decades after its creation, Moore’s terracotta ‘Reclining Figure’ was included in what would be deemed the most significant solo exhibition of his lifetime, held at the Forte di Belvedere in Florence, in 1972.

[Fig. 3] Reclining Figure, 1945-46, elmwood (LH 263) Photo: Henry Moore Archive

The human figure, enigmatically isolated or in relationship with others, is both the stimulus and the crux of all Henry Moore’s works. For him, creating his sculptures was not so much an abstract exercise in looking at the human figure, but a personal investigation and violation of the artist’s own body: ‘When I carve into the chest,’ he commented, ‘I feel as if I were carving into my own.’ Moore’s large-sized abstract sculptures can be encountered in numerous international public places (like Reclining Figure, 1956–58, UNESCO, Paris). Overlooked sometimes, are his fascinating drawings, often inspired by poetry and mythology.

Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Bahnhofstrasse 1

Located in Zurich’s historic central cultural district, the gallery’s new space at Zurich, Bahnhofstrasse 1 is open Tue – Sat, 10 am – 6 pm. Henry Moore’s ‘Reclining Figure’ can be viewed by appointment at the gallery.

[1] Email correspondence between Artist’s Estate and Hauser & Wirth, 18 January 2021. [2] Henry Moore quoted in Warren Forma, ‘5 British Sculptors (work and talk)’, New York NY: Grossman, 1964, pp. 63, 67. Quote: Henry Moore quoted in John Russell, ‘Henry Moore’, London/UK: The Penguin Press, 1968, p.28.