Conversations

Go Tell It on the Mountain

A conversation about art education, professionalization and the unorthodox history of Los Angeles’s Mountain School of Arts

Jorge Pardo, Untitled (The Mountain Bar Installation), 2009. Courtesy the artist and Petzel Gallery, New York

If, as The Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight once observed, “modern art began as an assault on the academy but post-modern art might be described as a return to the academy,” then Los Angeles has long been one of the world’s most important incubators of art, along with Dusseldorf and London. While the art world in New York is propelled primarily by the market and powerful museums, Los Angeles has provided an intellectual home and source of teaching income for generations of artists at schools like Otis, Chouinard, CalArts, Pomona and ArtCenter—attractive in large part as havens of experimentation, dialogue and determined nonconformism.

In 2005, the artists Piero Golia and Eric Wesley began to discuss their mutual feeling that this great art-school undergirding of Los Angeles was showing signs of erosion and that graduate art programs in particular had veered too far toward professional training, career planning and conventional pedagogy. Looking to free-spirit historical models of art education like the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College, the short-lived modernist hothouse in Asheville, N.C., the two artists founded the Mountain School of Arts (named because its first classes were held on the second floor of the artist-founded, now-defunct Mountain Bar, in Chinatown) as a radical alternative, or maybe just adjunct, to an institutional art education.

With no permanent location, no tuition, no paid faculty and an ambitious, highly unpredictable curriculum, the school has functioned for eighteen years now as something like a floating seminar and a permanent field trip, offering an ongoing, on-the-ground critique of both the art world and the idea of art education itself. Over the years, it has brought together students and thinkers from numerous fields, as well as established artists like Dan Graham, Pierre Huyghe, Henry Taylor, Simone Forti, Paul McCarthy, Richard Jackson, Tacita Dean and Myriam Ben Salah. (A book published on the school’s fifth anniversary, in 2010, provides a clear sense of both its approach and its irreverent personality; alphabetically organized by topic, the book, under the letter “T,” includes a fictive table of contents with headings like “Happy Hour Hermeneutics: The (Mountain) Bar as Classroom” and “Reflexivity and its Discontents: Breaking the Art-About-Art Cycle.”)

Recently, Golia sat down in the Los Angeles studio of Richard Jackson, one of the Mountain School’s earliest and most active teachers, and Debbie Hillyerd, the senior director for learning at Hauser & Wirth, to talk about the history of the school and the ever-evolving notion of what constitutes an art education. These are edited excerpts of their conversation, moderated by Julie Baumgardner.

“People go to school in kindergarten, and they get out when they’re twenty-nine in serious debt with a master’s degree. And their experiences are highly similar. They get out of school to find a world that’s unstructured.... What we’re trying to do is show them other kinds of experiences, experiences they haven’t had in ‘regular’ school.”—Richard Jackson

Julie Baumgardner: You two have been good friends for more than twenty years, and working artists in Los Angeles. Where does community fit into being an artist? What does an actual artist community look like in the 21st century, especially here in Los Angeles?

Richard Jackson: It’s hard to have art friendships in Los Angeles. Because, look, I live out in Sierra Madre. Artists are all over the place here. If you want to visit a friend, you have to get in the car. Yeah, so it's a little difficult, but people do go to openings.

Piero Golia: I always thought the magic of L.A. was exactly this. When I arrived here, L.A. was completely unevolved, socially. All galleries would do an opening, but it would be only the artist's friends. There were so few artists, so you could go to all your friends’ openings. Sadly, it’s not like this anymore.

RJ: It’s really hard. Here’s the whole thing about it. The art world is saturated with money—the only thing that seems to matter now. But we created the Mountain School and have kept it going despite that fact. Nobody gets paid. Good people are involved. The students don’t pay anything. And maybe they also don’t get what they pay for, which is nothing!

PG: You can’t complain and say, “I want my money back!”

Dan Graham (left) and students, 2010. Courtesy Mountain School of Arts

Simone Forti (right) supporting a group of huddled students, ca. 2000s. Courtesy Mountain School of Arts

RJ: I asked John Mason one time, “How are you doing?” Johnny says, “I’m doing okay.” I said, “You don’t make any money.” And he said, “Yeah, but I can’t be fired.” I said, “Well sure, but you can’t be promoted either.” The thing is for me, when you look at it: People go to school in kindergarten, and they get out when they’re twenty-nine in serious debt with a master’s degree. And their experiences are highly similar. They get out of school to find a world that’s unstructured. They’ve never been taught how to structure the world and go on without something like school around them. So they’re looking for things like the Mountain School. What we’re trying to do is show them other kinds of experiences, experiences they haven’t had in “regular” school. By the way, most of the people who give their time to the Mountain School average about seventy years old. They’re bringing a lot of experience and life and perspective.

PG: The people we invite to teach are all really good at what they do; they are people who have dedicated their lives to what they do. And I will say that in eighteen years, I’ve only gotten two hard no’s from people I’ve asked to teach.

JB: Have you had any other difficulty bringing in talent, convincing people that the school is absolutely serious?

PG: Well, Dan Graham would teach every time we asked him. But on one condition: The only pay for Dan was mandatory architectural trips, meaning that every time, we had to take him to see a new architecturally important home. At one moment, he was in a John Lautner period. I remember that I was so desperate, because I had burned all my Lautner connections. So I call Richard. I'm like, “Richard, how do we get Dan to fucking do this?” He’s like, “Go call Dagny Corcoran, the great Los Angeles book-seller. She knows everyone in town.” So I call Dagny. And I’m like, “Dagny, please, do you know a good John Lautner house?” And of course she got us in with Jim Goldstein, whose Lautner house is so great that it’s going to the collection of LACMA when he dies, though I don’t think he will ever die. And that’s how Dan Graham kept being a professor.

Debbie Hillyerd: What do you feel is important to impart to students at the Mountain School? I don’t want to use the word “teach” because I don’t think it is about teaching, as commonly understood. It seems to be more about sharing, guiding.

RJ: Number one: You have to tell them about content. Art is a serious matter and there’s content. It’s not just splashing around making something pretty. So you give them a little bit of history. So you show them work and you tell them about the content. You tell them to challenge authority. The whole art community is like what Ed Kienholz told me once: “It’s a balloon and you’re on the outside, pushing, trying to get in. Next thing you know, you’re inside pushing to get out.” I didn’t go to school. The reason was because I realized the people who were teachers weren’t really artists. I try to make the best work that’s possible for art’s DNA. And I want to be known for that. I don’t want to be known for how I blew warm milk up everybody’s ass and they bought my work. I think you have to challenge authority. Things are screwed up. And you have to confront them. I mean, the thing that I’m afraid of is people coming to Los Angeles by the thousands with master’s degrees. They want to be here for the same reason people want to be here to get into the movies or the music industry, same damn thing. And this is the place that washes them out.

Paul McCarthy (left) with students at The Mountain Bar (constructed by Jorge Pardo), 2011. Courtesy Mountain School of Arts

Richard Jackson (middle) and students installing the Mountain School of Arts tent on the beach during Art Basel Miami Beach, ca. 2003. Courtesy Mountain School of Arts

PG: It is very complicated. The concept of school is usually: You go to Harvard Law School. You come out. You pass the bar. You are a lawyer, officially. You go to court. If your client goes to jail at the end of the day, it’s very clear you lost. If the guy is out robbing another bank, you won. You are a good lawyer. Right? But art is something different. There is no way to know if what you do is right, there is no winning or losing. Art is about the experience you create for people. Doing Mountain School is about always trying to do something that we’ve never done before. Every time starting from scratch with a full new experience, a new format, a new building, a new story. We do things because they need to be done. We try to bring incredible people together and build something that people will never forget. Something that will stay forever. I don’t think you’re going to get something like that at Harvard.

RJ: There are a lot of parents now who think it’s all right for their children to go into the art world, a place very few parents would have once thought of a responsible field, a good vocation, a normal thing to do. A guy who worked for me told me: “Well, it’s a big industry.” I never thought of art as an industry, but now it is. And there are a lot of jobs that revolve around it. And you can see these normal fucking people creeping in now, polluting it. But then again, that’s what’s good about those people—they give you something to push against, you know what I mean? Normalcy. And not only that, they support me. I mean, somebody has to make the money.

“We have an advantage. You didn’t give us any money. You don’t have any debt from us. And I think this puts you in a condition of freedom. The magician knows who is the real magician; the artist knows who is a good artist.”—Piero Golia

PG: Every artist who doesn’t do highly commercial work needs at least one very expensive painter to pay for the gallery ... like to pay for all my Fedex. [Laughing.]

DH: You can’t teach students to become the big blue-chip artist or to become the artist who wants to work under the radar, either, I don’t think. You can only make them aware of those contexts; which part of the art world they aspire to be part of. And, as you say, it’s now a massive industry.

JB: The school has been around long enough now that people do talk about it as making a kind of magic against the backdrop of this growing industry.

PG: Don’t give away the secret! Everyone will try to copy us.

JB: What kind of criteria do you use to determine who you let into each year’s classes?

RJ: Number one: Do they really want to do it?

PG: There’s been a change in expectations. Capitalism has established a mentality: “Here is what you need. You have to pay for it.” If you paid $200,000 for the education, you expect to make at least $200,000 a year from it or you feel like it failed out. We have an advantage. You didn’t give us any money. You don’t have any debt from us. And I think this puts you in a condition of freedom. The magician knows who is the real magician; the artist knows who is a good artist. How do we find students? Maybe we don’t find them. Maybe people are meant to find each other.

JB: And what about the students? How do you want them to contribute?

DH: Can I interject with a question? Do you call them students?

PG: Yes. Very much. And maybe they don’t like it. If you want to be loved, you call them artists, you invite them to join as artists, not students—but then you are baiting. It’s the Instagram thing: If you post the cat pictures, you get more likes. At the end of the day, here, they are students.

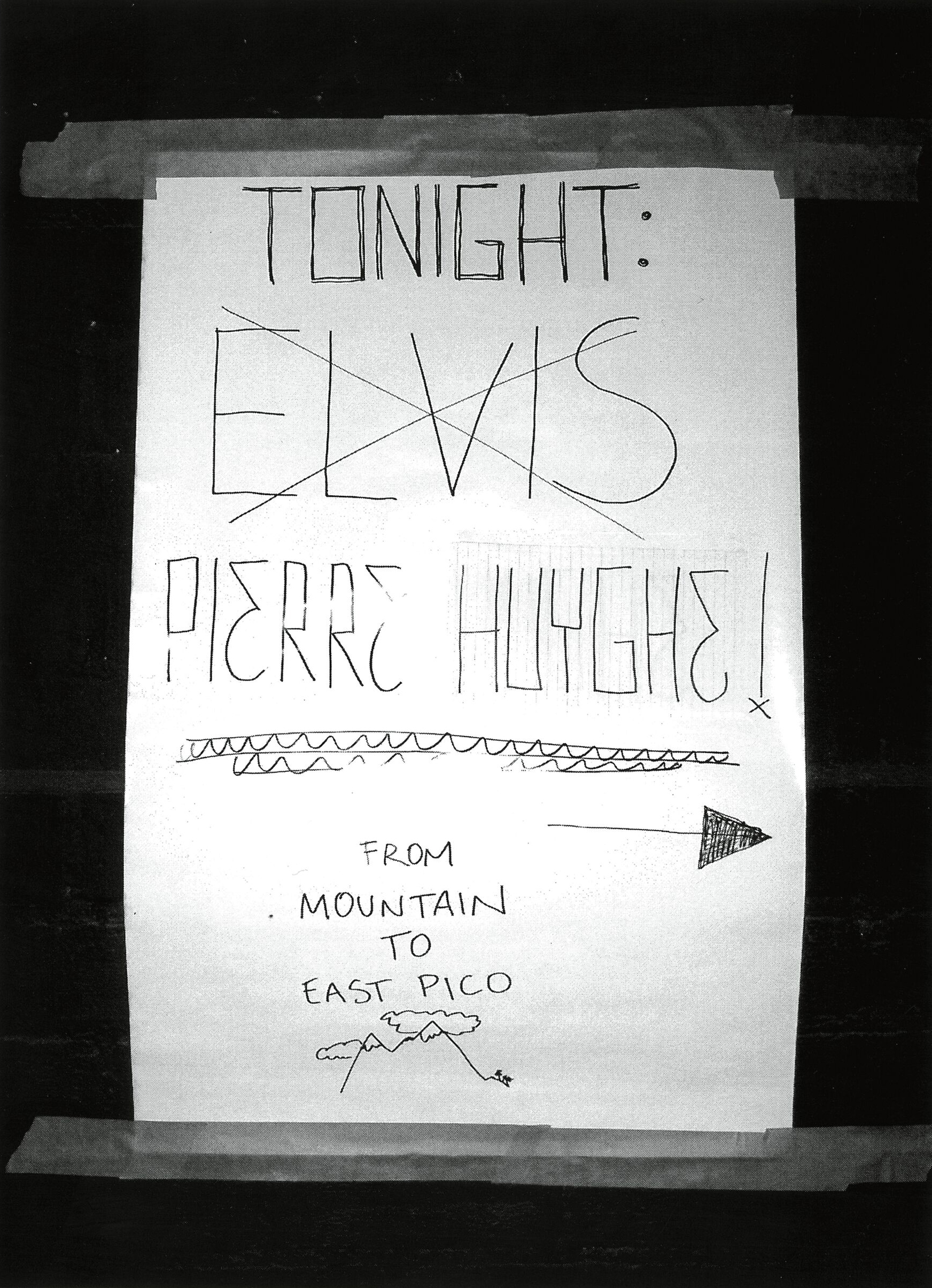

Pierre Huyghe poster, 2007. Courtesy Mountain School of Arts

Mountain School anniversary poster, ca. 2000s. Courtesy Mountain School of Arts

RJ: We have fifty people with very different backgrounds, and we put them all together, and they kind of inspire and push each other and give each other something, learn from each other. I’m only one person. I only have so much I can teach. And I end up learning, too. The students I once had at UCLA, they didn’t know how to make anything. They grew up in families that had libraries and were very, very smart, but they couldn’t make anything. Everything looked like shit. They had great ideas, maybe, poorly executed. But in retrospect, maybe that was better. Because now in art school you get these really shiny, nice-looking things coming out of those programs—things that look like they’re polished up and ready for the market.

JB: When you started the school, did you feel that graduate art programs were becoming too much about career, about professionalization? Were you pushing against that system?

PG: We’re not just about reacting against a system. But at the same time, we do not wear ties. We do not have a website, or least we don’t have a good one. We don’t give you a degree. We don’t give you a studio. We don’t give you any money. It is a completely new universe with no model, no structure. This gives you the chance to create something that is a human experience for students. For me, art is about the future. You can learn it only from those people who can see things that other humans cannot see yet. Artists belong to the category of encyclopedia, meaning: You have to know the world to be able to build the future. When I think about the Mountain School, I also think about the difference between a model and a platform. In a model, you have an organization, and people are obliged to follow that organization. A platform, instead, is like an open landing field. I invite you to do what you believe you’re very excited to do. So there is no model, because I don’t know what is going to happen—and I always assume that everybody knows that. That’s part of it. You should be doing it for free. Because it’s part of what you choose to do in life. You are here for other people.

RJ: That’s why they call it the humanities.

PG: It’s a big misconception if people think of this school as a kind of hippie thing. I’m an ’80s kid. I believe in hard work. I wake up at four-thirty in the morning and work. I think probably that’s why Richard and I are friends. We call each other at five-thirty, six in the morning and have long conversations while everybody else is sleeping. Education, at the end of the day, is work. And also, what you really learn from school is: You make friends.

RJ: I’m a perfect example. You know what my school was? I’m Bruce Nauman’s friend. I was Kienholz's friend. I’m Paul McCarthy’s friend...

PG: The grumpy motherfuckers’ club! [Laughing.] I don’t want to be the waiter coming to that table!

–

Julie Baumgardner is a writer and editor who has spent nearly fifteen years covering the arts. Her work has appeared in Bloomberg, Cultured, Financial Times, The New York Times and other publications.

Piero Golia, born in Naples, Italy, lives and works in Los Angeles. Golia pushes the boundaries of art, blurring the margins between sculpture, installation, performance and architecture. Golia’s work has been exhibited at LACMA; the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam; MoMA PS1; the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas and other major museums. He co-founded the Mountain School of Arts in 2005.

Debbie Hillyerd is Hauser & Wirth’s senior director for learning, overseeing the development of education and charitable projects across the organization. Previously, she lectured at Bath Spa University in England. She writes and consults for various institutions in the education sector.

A preeminent figure in American contemporary art since the 1970s, Richard Jackson is influenced by both Abstract Expressionism and action painting. His performative process extends the potential of painting by upending its technical conventions. Jackson responds to the high-mindedness of painterly practice by repositioning painting as an everyday experience, drawing on the visual lexicon of domestic environments, basic human activities and aspects of everyday American life such as hunting and sports.