Essays

The Frisson of Difference

A reading of the intricate sculptural language of Thomas J Price

By Charlotte Jansen

Detail of ‘Signals’ (2021) © Thomas J Price

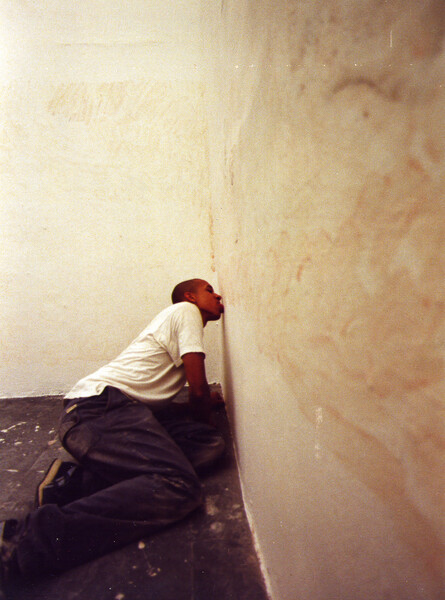

At a student house party in London some time in 2001, a boozed-up stranger started talking to Thomas J Price about a radical performance-art piece he’d heard about, one in which ‘some guy licked the walls of a gallery for three days straight until his tongue was bleeding’. It turned out that Price was the ‘some guy’ and that it was his blood and saliva that had accrued on the walls of that gallery.

Then a 20 year-old student at the Chelsea College of Art, Price had booked a gallery space at the school for a durational performance piece that was intended to become an invisible installation by the end, the only residue being the imperceptible coating of his saliva on the walls. Visitors were invited to stop by and gawp at the action through a gossamer sheet of plastic. People did come to watch, and as Price stooped and craned his neck to make contact with the wall, daubing a wet flannel as he moved along, his mouth full of the iron taste of blood (he hadn’t anticipated the bleeding) he recalls clearly, with anguish, the sounds of revelry that came from the surrounding studio spaces: ‘There I was trying my hardest—mentally and physically I'm exhausted—and people around me are laughing. And I just thought: This is my life.’

Thomas J Price, 2021. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

The artist’s 2001 performance, ‘Licked’

The performance was titled ‘Licked’—the past tense intended to direct the viewer to the action of a body that had passed through the space. This was two years after Tracey Emin’s blood-stained underwear was exhibited at the Tate as part of her installation ‘My Bed,’ and six years after Franko B’s cleansing bloodletting in his performance ‘I’m Not Your Babe.’ The previous year Price had seen ‘Sonic Boom,’ the Hayward Gallery’s big group show devoted to sound art, which had opened his eyes to the possibility that art could be an idea or an experience. Those were the halcyon days of the YBAs, who helped pave the way for working-class artists to make it in an art world that had long been rigged in favor of the few. ‘Licked’ resonated with the YBAs’ signature shock tactics, but as Price explains, he was less interested in provocation than in exploring the unconscious. ‘Licked’ was conceived as an expression of presence in absence, of being in a room but not being seen, as well as a demonstration of a deep desire to connect, to become literally a part of a place and its physical, material history. Although it is the only performance work that Price has made, it constituted a breakthrough, and has continued to shape his work and thinking to this day.

Twenty years later, I’m watching the video documentation of ‘Licked,’ and it still emanates a gut-wrenching power. It takes me back to my own experiences in 2001, as an awkward fifteen-year-old, growing up as a mixed-race woman in a shithole in the southwest of England; an entirely different world from Price's childhood spent in southeast London, where he was exposed to art from a young age and was well acquainted with galleries and museums. And yet ‘Licked’ taps into something we shared: a desire to be believed. Watching Price lick walls is an excruciating sensation, like nails on a chalkboard. It’s the way that the rhythm of the simple, repeated gesture becomes stronger and more emphatic as he breaks down, depleting himself. It’s an effective metaphor for the crisis of the human condition—what Camus meant by the dialectic of absurdism, that the more desperate we are in searching for meaning, the more we discover there is none. In its raw, sensual urgency ‘Licked’ is an attempt to bridge the unbearable void between language and meaning, to find a visual form for the subliminal.

‘[Price’s sculptures] are Duboisian representations of misrepresentation, psychological portraits of the white psyche.’

In Somerset, ‘Thoughts Unseen’ presents two decades of works by Price. Photo: Ken Adlard

The series of figural sculptures Price has made since 2013, ‘Network’ (2013), ‘Within the Folds’ (2020) and ‘The Distance Within’ (2021) now installed in Marcus Garvey Park, Harlem, monumental in scale and stature but as intimate in feeling as ‘Licked,’ are often misread as the very thing they critique: the harmful stereotyping and persistent profiling of Black men. But these are not representations of athletes, as they’re often misinterpreted. They are amalgams drawn from the essentially abusive images of people of color in the public realm, a history that reaches back to ancient statuary. They are Duboisian representations of misrepresentation, psychological portraits of the white psyche. For us, the others, they are also affirmations, allowing us to imagine what it would be like to inhabit space neutrally without the frisson of difference that fizzes around our bodies when we step into white-dominant spaces. They are nuanced statements about simply being. While it's impossible to ignore the politics inherent in any figurative work seen within a systemically racist society, to view depictions of people of color only through the prism of race reflects the same issue of endemic racism. In fact, when Price is most explicit about racism, it’s in his abstract works, the luxurious polished bronze ‘Power Object (Section 1, No 1)’—a direct reference to the police’s power to stop and search any person they suspect of carrying dangerous or prohibited items—in other words, the ability to detect threat in abstract form. The overly large, lumpen ridiculousness of the sculpture parodies the Modernist sculptures of white male artists, reimagined from the knowing perspective of someone who has experienced the malevolence of objectification.

Though Price hasn't returned to performance, performativity—exposing by showing the moments where the mask drops—remains important in all of his works. In his stop-motion ‘Man’ series (2005 – 2012), he explored the inner workings of the soul that surface in the eyes; each film portrays a male protagonist, a head moulded in plasticine, the only movement being the blinking and shifting eyes. Each of these men is once again a composite, generically titled by number, but they are based on Price's observations of real men when they weren't aware of being watched: a hotshot gallerist spied in his office, staring into space; a gentleman lost in thought while eating on the bus. With his intense focus on facial expressions, eye movements and the emotions they evoke, Price digs deeper into the subconscious, suggesting that ‘freedom is to not have to pretend,’ as he puts it.

‘When he asks in his sculptures ‘What if, instead of celebrating excellence, we acknowledge the ordinary?’ he turns the grand gesture of the monument on its head.’

Thomas J Price, Power Object (Section 1, No.1), 2018 © Thomas J Price. Photo: Damian Griffiths

Thomas J Price, Corrance Road, Figure 1, 2008 © Thomas J Price. Photo: Ken Adlard

I see Price as aligned with feminist ideals, in that his works reflect the emancipatory effect art can have. In his focus on the construction of male identity, his work is anti-patriarchal as well as being anti-imperialist, and he has recently begun to work with women figures, too. When he asks in his sculptures ‘What if, instead of celebrating excellence, we acknowledge the ordinary?’ he turns the grand gesture of the monument on its head. The statue gains the ability to be liberated from its past, ‘not having to be something spectacular in order just to be seen as marginally valuable, or marginally okay,’ as Price says. They are indeed sometimes spectacular in their size: the 12ft bronze sculpture first installed in Somerset, ‘All In’ (2021) towers above the viewer, but in doing so it does not suggest that dominating space is a solution to being understood. In their making, the sculptures speak partly in the language of sculpture’s past. Price employs the classical craft of lost wax casting, whereby molten metal is poured into a mold made with a wax model that melts and drains away. But the pieces function as something beyond markers of craft and career and monumentality.

The vitality in the work lives in its attention. In a highly networked world of crossed wires and mixed messages, pithy captions and comments, truncated texts and disembodied voices, Price's work tries to re-establish human contact and context. In ‘From the Ground Up’ (2016), a 26-minute dual-screen video work in which Price tends to his shoes, from Nike trainers to leather dress brogues, he acknowledges that in a consumer-lead, material culture, such objects have a talismanic quality. The repetitive, meditative effect of cleaning and lacing shoes evolves into a meditation on the ways in which we create value for ourselves within the oppression. For me, the footwear can also be coded, signaling classism and racism. By dismantling the conventions of communication, the subliminal messages, signs and symbols, Price renders the machinations of society visible to all. In considering him, another existentialist thinker comes readily to mind, Italo Calvino, who wrote that ‘everything can change, but not the language that we carry inside us, like a world more exclusive and final than one's mother's womb.’ Price’s entire body of work reflects profound empathy for people who must numb their truth in order to survive, and in doing so it comprehends that language within.

–

Thomas J Price’s first exhibition with Hauser & Wirth, ‘Thoughts Unseen,’ is in Somerset, 2 October 2021 – 3 January 2022. View ‘Thomas J Price: Witness’ presented by The Studio Museum in Harlem, at Marcus Garvey Park NY, 2 October 2021 – 2 October 2022.