Essays

Zadie Smith on Henry Taylor’s Promiscuous Painting

Henry Taylor, Cicely and Miles Visit the Obamas, 2017 © Henry Taylor

- 15 October 2020

- ‘Henry Taylor’s Promiscuous Painting’ by Zadie Smith. Published by Rizzoli US, 2018. Copyright © Zadie Smith. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN

- Related Artist

- Henry Taylor

The California artist’s subjects are drawn from wildly divergent walks of life—the famous and the down-and-out, the sane and the mad, the rich and the poor.

Not quite two months after the Presidential Inauguration, a Henry Taylor painting appeared on the cover of Art in America: ‘Cicely and Miles Visit the Obamas’ (2017). In this portrait, the Obamas are invisible, represented only by the house they’d just left, while the actress Cicely Tyson and her lover Miles Davis have been transported from a long-ago black-and-white society photograph onto the green impasto glory of the White House front lawn. Transported? Transmogrified. The original paparazzi snap is from the 1968 première of ‘The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter,’ a film in which Tyson had a supporting role—in 1968, a black actress could rarely expect more—and she is playing a supporting role here, too. The nature of this support is interesting. Her hand is on Davis’s sleeve, a gesture somewhere between solidarity and protection. Her gaze is steely: as proud and firm as it is guarded. (Meanwhile, his shades are on and his arms are crossed, as if the camera were some sort of weapon.) The support she offers is not meek or retiring (‘Behind every great man . . .’), nor is it hidden or oblique (‘The power behind the throne’). Instead, it speaks of a double consciousness. On the one hand, her lover is that unimpeachable thing: an American genius. Why should Miles Davis need anyone’s help or protection? On the other hand, he is a black man in America. The same black man who, nine years earlier, found himself beaten up by a New York cop for the twin crimes of escorting a white girl to a cab and not ‘moving on.’ (He had been standing outside Birdland, where he was playing a concert for the U.S. armed forces.) Davis’s name was up in lights, but Davis himself was laid out on the pavement: blood ‘running down the khaki suit I had on,’ as he later recalled. If you can be assaulted outside your own show, you might come to experience many apparently benign situations as rife with the potential for humiliation or violence. It’s 1968: best be on your guard. But to be on your guard—unsmiling, self-possessed, not in need of anyone’s approval, and dressed like you know your own worth—is also to be cool. Cool as a motherfucker. And surely one obvious way to read this translation of Miles and Cicely to the Obamas’ front lawn is as a form of transhistorical wish fulfillment. What if these cool cats met those cool cats? Yet to speak of this painting as I have—conceptually—is to pass over the difference between thinking with language and thinking in images, and no narrative explanation of the relation between these two pictures is as compelling as the horizontal line that marks the credenza in the photograph and the edge of the White House gardens in the painting, or the verticality of the white man in the photo’s top-right corner—with his squared-off shoulders—and his painterly analogue: a blue flagpole, with its crossbar and absence of flag. Taylor thinks primarily in colors, shapes, and lines—he has a spatial, tonal genius. Form responds to form: the negative space around Cicely and Miles in the photograph suggests the exact proportions of the White House, yet in the transition the abstract sometimes becomes figured, and vice versa, as if the border between these things didn’t matter. A burst of reflected light in the photo decides the height and placement of the windows in the painting, while two round signs at the movie première—one for Coca-Cola, the other for ‘Orange’—which can have no figurative echo in the painting, turn up anyhow on the White House façade as abstraction: a red sphere and an orange sphere, tracking the walls of what, in reality, now belonged to Trump. Like two suns setting at the same time.

Henry Taylor, Screaming Head, 1990 © Henry Taylor

Henry Taylor, The Darker the Berry, The Sweeter the Juice, 2015 © Henry Taylor

What kind of a painter is Henry Taylor? He is described by others with labels he mostly rejects—outsider, portraitist, protest painter, folk artist. ‘I think I just hunt and gather,’ he has said. ‘I feel sort of voracious.’ It’s his practice to seek people out—in the street, at an art fair, at his mama’s house—and figure them in paint, but each person is configured differently, sometimes hewing closely to verisimilitude, sometimes ignoring it; sometimes attending to the proportion of limbs, other times leaving them out entirely. This variousness of approach finds its mirror in his life, which has also been a story of many different elements combined. Born in 1958, the youngest of eight children (he often refers to himself as Henry the Eighth), Taylor was raised in Oxnard, California, where the pictures in the fancy houses his mother got paid to clean provided some of his earliest exposure to art. Paint itself he might be said to have come to know through his father, a commercial painter employed, for a time, by the U.S. government at a naval air station in Ventura. (He also painted local houses and bars.)

His subjects are drawn from wildly divergent walks of life—the famous and the down-and-out, the sane and the mad, the rich and the poor...

Taylor spent many years in community-college courses—in subjects as disparate as journalism, anthropology, and set design—before taking a job as a psychiatric technician at Camarillo State Mental Hospital. At Camarillo, where he worked for a decade, he began, in his free hours, painting portraits of patients and studying for a B.F.A., at the California Institute of the Arts. He has been painting ever since, at a prolific rate, and on many surfaces besides canvas, including cereal boxes, suitcases, packs of cigarettes, bottles, furniture, and crates. The materials and the style may vary, but the inspiration stays constant: people. (‘First of all, I love other people,’ he told Hamza Walker, the executive director of LAXART, in a recent conversation in Cultured magazine. ‘I love to meet them, and the fact I can just paint them.’) His subjects are drawn from wildly divergent walks of life—the famous and the down-and-out, the sane and the mad, the rich and the poor—and the work they inspire has been similarly unpredictable: poignant faces and blank masks; social realism and fantasy; the handmade, the readymade, and the mixed-media sculpture; the multimedia ‘happening’ (featuring real-life Rastas smoking real-life weed); as well as eclectic borrowings from Alice Neel, Basquiat, Degas, Rauschenberg, Matisse, Goya, Whistler, Alex Katz, Cubism, Constructivism, Congolese sculpture, and more.

Henry Taylor, Man on Horseback in Naples, TX, 2015 © Henry Taylor

Henry Taylor, I Am a Man, 2017 © Henry Taylor

If it has been the tendency of African-American artists to stray heedlessly across academic borders and genre demarcations (rap is popular poetry; jazz produces improvised symphonies; gospel is the sexual sacred), then Taylor is firmly grounded in the African-American aesthetic tradition. His greatest subject is human personality, although, in his portraits, personality is not a matter of literal representation but rather a vibe, a texture, a series of vertical block colors laid out on a horizontal plane. This re-states the obvious fact that seeing is never objective, but the intense level of empathy we meet with in Taylor’s portraits, especially between the artist and his African-American subjects, determines everything we see, from brushstroke to framing to gaze. Take ‘Elan Supreme’ (2016). Elan is that admirable friend: a sista who has her shit together—despite all obstacles placed in her path—who is permanently glued to her iPhone, working at the top of her game, with no time at all for anybody’s nonsense. There are echoes of Cicely here (the word ‘support’ seems to be etched along the horizontal. Or is it ‘suppress’? Or is it ‘supp’?), but the energy is different; Taylor’s brushstrokes tend frantically rightward, as if his subject were about to walk out of the frame at any moment to take a conference call. ‘A young master’ (2017), meanwhile, is your wiliest little cousin, the one who plays 4-D chess in his mind and may yet grow up to possess the kind of Machiavellian mastery of the streets that will mean, in turn, that the streets can’t defeat him. ‘My Brother Randy’ (2008)—one of multiple portraits of Taylor’s sibling—looks like one of those naturally buoyant brothers, filled with wild philosophy, whom you can only pray that no oppressive counterforce will ever step on or stop.

‘To be known and seen’ is swiftly turning into a twenty-first-century cliché, but, as far as it regards black life in America, it remains an urgent necessity.

Which is all to say that there is a profound sense of recognition and familiarity in Taylor’s work, not only between painter and subject but between painter and community, there being so little anthropological distance between the two. (Taylor, who used to live in a loft studio in downtown L.A. and now lives in West Adams, regularly invites neighborhood types to hang out in his space, to drink and talk or be painted—often all three.) There is, additionally, an interesting division between Taylor’s paintings of local subjects, frequently homeless or otherwise down on their luck—and usually black—and the art-world denizens, mostly white, he sometimes paints. In the first group, he captures the unstudied openness of those who have no sense of formally presenting themselves. (One painting, from 2014, is called ‘You Really Gone Pay me to Sit?’ . . . said the panhandler.’) In the second, we can observe what it means to present oneself as a subject for a portrait by Henry Taylor. Here arms or legs get crossed, eyes turn a little wary or defensive. There is a difference, perhaps, between self-presentation and being present. ‘To be known and seen’ is swiftly turning into a twenty-first-century cliché, but, as far as it regards black life in America, it remains an urgent necessity. ‘why look, when you can see’ is a recent Taylor title but might also serve as a ruling principle of his work. He paints children at play with their toy guns, undercut with explanatory titles (‘I’m not dangerous’ and ‘Girl with Toy Rifle,’ both from 2015) intended, perhaps, for those who can’t see a black child for what she is—i.e., a child. And Taylor knows that it’s all too easy to look but never truly see the ‘Haitan working (washing my window) not begging’ (2015), whom he paints in rough but affecting profile, capturing so much: pride, intensity, stoicism, and simple beauty.

Henry Taylor, THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!, 2017 © Henry Taylor

Other people look; Taylor sees. He puts himself in the way of people. His door is open to all kinds of folks at all kinds of hours.

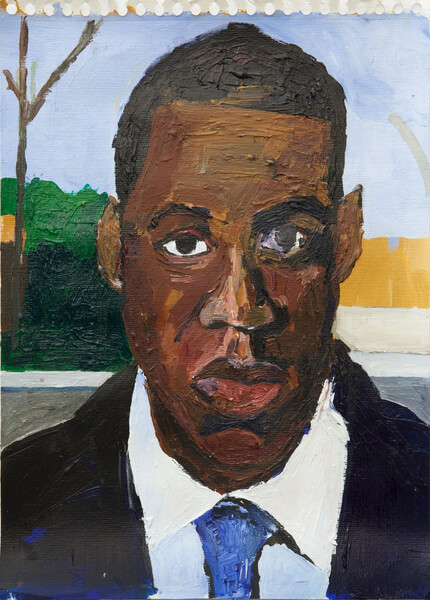

This is painting that goes way beyond the brute fact of a body. Other people look; Taylor sees. He puts himself in the way of people. His door is open to all kinds of folks at all kinds of hours. In a different place, this simple fact wouldn’t feel so surprising, but in twenty-first-century L.A.—as throughout America—cross-class and cross-economic encounters are regulated and separated by gates, districts, ghettos, railway tracks, walls, and income brackets. Skid-row strangers rarely cross these lines except to be utilized in some form of transaction, often exploitative (prostitution, drug dealing). Taylor, by contrast, asks nothing of them but their presence, and in a heavily defended culture, rendered potentially lethal by the Second Amendment, this rare openness (‘I love other people’) feels pointedly radical. The poor, the marginalized, the addicted, the mentally ill, the desperate and forgotten—everyone is of interest to Taylor, and whatever is risked by this faith in strangers (‘So far so good,’ Taylor told Modern Painters. ‘One girl stole my CD player.’) is laughably minimal when placed next to the gains, both artistic and personal, from the encounters themselves. And, of course, they’re not always strangers. As Taylor has explained, ‘Every successful black person has eighteen members of his family living in the projects, and we all know someone who’s in the system.’ This unique aspect of African-American life means that getting to the ‘top’ never entirely shields you from the ‘bottom’ (or doesn’t allow you, in good conscience, to forget all the people you’ve left behind). It is a painful fact that functions structurally, in his work, to create interesting time signatures, where the past, the present, and the future meet in traumatic collisions. ‘Go Next Door and Ask Michelle’s Momma Mrs Robinson if I Can Borrow 20 Dollars Til Next Week?’ (2017) is a reference to Michelle Obama’s mother and features a figure in a Colin Kaepernick jersey looking keenly through bars at two buildings: the White House and Marcy Projects, the Brooklyn public-housing complex in which Jay-Z was raised. Elsewhere in the painting, a gaggle of men are about to enter the county sheriff’s department’s white van, followed by an ominous-looking black horse. (Horses, in Taylor’s work, appear sometimes as a symbol of freedom and power and sometimes as an expression of the opposite: power restrained, power trapped and fenced in.) It is a painting that exists in many moments in time—in a moment of success and in one of struggle, in the everyday present/past of black oppression and imprisonment and in the aspirational present/future of black success and freedom. Horizontal strips of tree and fence and pavement mark these divisions, but not cleanly. If Marcy were on the prisoner side of the fence, for example, it might be possible to separate the painting out chronologically, into the dark past and the bright future. But Taylor depicts black history the way many black people actually experience it: as simultaneous change and stasis, revolution and stagnation, one step forward, two steps back. In Taylor’s work, the dream is not to finally and speciously separate these two worlds of struggle and success, as O. J. Simpson notoriously attempted to do, but to insist on their relation. The individual black success story—including Taylor’s own—is not sufficient. An awareness of the proximity and the ever-present threat of poverty and abjection connects Taylor’s work to the hip-hop that he loves and references, mining Kendrick Lamar’s lyrics for titles or using Tupac’s face for an installation, and painting several lively portraits of rappers themselves. A 2017 portrait of Jay-Z, neither sat for nor gleaned from a photograph, was instead constructed from memory, and so we can rightly describe it as an imagined portrait of an Old Master: besuited, unruffled, arrived. And, considering the way that Taylor plays with time, it’s pleasant to think of this portrait as existing in a fantasy chronology with ‘A young master,’ as if that determined young boy might be another kid from Marcy Projects with big plans, one of the future black success stories Jay-Z himself anticipates in the song ‘Murder Excellence’: ‘That ain’t enough—we gonna need a million more.’ But even Jay-Z, in Taylor’s version, has not escaped the strictures of racialized America. The confidence of the portrait is deliberately undercut by its title, ‘I Am a Man,’ which, with its mixture of pride and a still necessary defensiveness, has melancholy roots you can trace all the way back to the abolitionists: ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’ Celebrating black success is one thing, but Taylor never seems to forget the many other possible futures awaiting a boy like this young master, possibilities that are, statistically speaking, far more likely than a superstar rapper’s miraculous trajectory. Take Taylor’s neighborhood friend Emory, painted multiple times over the years but never more movingly than in the canvas titled ‘Emory: shoulda been a phd but society made him homeless’ (2017). Was he once a young master? In this portrait, we find him an old man, in utter isolation, gray-haired, raggedly dressed, barefoot in a motorized wheelchair. But he has been seen by Taylor. Known and seen.

Henry Taylor, See Alice jump, 2011 © Henry Taylor

There is a Picasso-like restlessness to Taylor, a determined promiscuity of intention and execution. You can well imagine a gallerist pleading with him to slow down. The artist who once, back at Camarillo State Mental Hospital, painted a suffering patient synecdochically, with a screaming mouth for a head, could have easily become a commercial artist, using the part to represent the whole, pitching and selling on either side of the horizontal line that bisects so many of his canvases. He could have been a maker of icons and iconography, like Warhol, who made a Campbell’s soup can a metaphor for capitalism and made repetition itself a metaphor for fame. Instead, Taylor has chosen the road of chaos—that is, the road of paint. Freewheeling through references in his voracious desire to render his subjects truly visible, he retools Degas’s existential mixture of boredom and desire in ‘La Coiffure’ (circa 1896) so that a bored homey can get his braids freshened (‘Gettin it Done,’ 2016), and borrows some of Barkley L. Hendricks’s graphic flair and advertorial slickness for his portrait of the ice-cool drummer/rapper—and his fellow Oxnard native—Anderson .Paak (‘PAAK,’ 2017). In ‘Two brothers (Afrikans) Relaxing in a Paris Park’ (2014), you sense that you will surely find Manet’s luncheon just out of frame, in the next clearing, while elsewhere, in ‘Before Gerhard Richter there was Cassi’ (2017), Richter’s famous ‘Betty’ becomes Cassi, with an Afro. The influence of the masterly Kerry James Marshall—Taylor’s contemporary and fellow L.A. painter—is many times explicitly quoted, with something of the same guilelessness and love with which Taylor opens his doors to his neighbors. In paintings like ‘Fatty’ (2006) and ‘The Darker the Berry, The Sweeter the Juice’ (2015), Taylor’s subjects are so dark that they appear, as they often do in a Marshall canvas, almost as silhouettes. But the most affecting works see the world in a manner that is wholly Taylor’s own.

The challenge is to see how it feels to be shot—the world-destroying pain that arrives with the bullets, as reality streams away from you—and the way that people and things begin to dissolve, becoming colors and shapes, then outlines, then nothing.

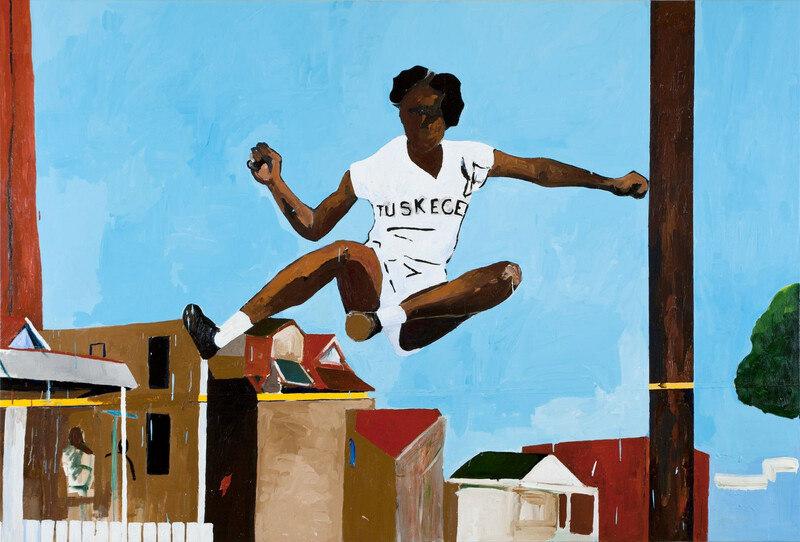

No one else could have painted ‘See Alice jump’ (2011) or ‘The Long Jump by Carl Lewis’ (2010), in which African-American sports stars leap through the artist’s beloved horizontal, and thus through time, through neighborhoods, through black history itself, offering a vision of the heroic that lives alongside the prisons and the projects, and that exists despite those things, yet does not, could not, erase or justify them. Taylor sees in the round. And he sees most acutely the things from which we may wish to turn. Things like Philando Castile bleeding out in the driver’s seat of a car (‘the times thay aint a changing, fast enough!’). The first time I came across that painting, at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, I thought for a moment that it was a presentation of a single eyeball—which, like all Taylor’s eyeballs, reminded me of the eyeballs found in Congolese nkondi statues—existing independently of a face, set instead within a frame of collagelike colors and shapes. Then I saw the face, then the car, then the blue twist of the seat belt, and only after I’d read the title did the little black rectangle atop the pink ball of paint resolve itself into a gun in a white cop’s hand. But I don’t think my first instinct was entirely wrong. As viewers, we are being asked to do more than merely look at an infamous shooting. The challenge is to see how it feels to be shot—the world-destroying pain that arrives with the bullets, as reality streams away from you—and the way that people and things begin to dissolve, becoming colors and shapes, then outlines, then nothing. For Taylor, this outrage from the newspapers becomes a pietà, driven by an intimacy based not on actual acquaintance but rather on personal identification. And this identification must be intense: his own grandfather, Ardmore Taylor, a horse trainer from East Texas, was ambushed, shot, and killed, back in 1933, when Taylor’s father was only nine years old. But many African-Americans will recognize the catechism: Could have been my cousin. Could have been my brother. Could have been me. – This essay is from the 2018 Rizzoli monograph ‘Henry Taylor’, with additional contributions from Sarah Lewis and Charles Gaines. Zadie Smith is the author of novels ‘White Teeth’, ‘The Autograph Man’, ‘On Beauty’, ‘NW’, and ‘Swing Time’, as well as two collections of essays, ‘Changing My Mind’ and ‘Feel Free’, and the recent publication ‘Grand Union: Stories’ (2019).

‘Henry Taylor’s Promiscuous Painting’ by Zadie Smith. Published by Rizzoli US, 2018. Copyright © Zadie Smith. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN