Conversations

Roni Horn and Matthew Barney in conversation

‘Well the illusion of going back is just that, it’s never more than an illusion, it’s a desire, it’s a wish, but it’s not an option’

Matthew Barney talks with Roni Horn in upstate New York from the Sawtooth Valley in Idaho, where the surrounding nature seeps to the surface of conversation, drawing out the textures of vast landscapes across Iceland and the US, in memory and imagination. In acknowledging the strangeness of disembodied Zoom communication and the subsequent disruption to our reality, ‘the sense that meaning is shifting’ as Horn says, the artists turn to the view from their windows: ‘there is that lake that you cannot get lost on… A lot of birch trees, white birch, really delicate clumps of birch. They’re very erotic and they're very tender and vulnerable.’

Excerpt from Roni Horn and Matthew Barney in conversation from upstate New York and the Sawtooth Valley, April 2020

Matthew Barney: You're upstate, right?

Roni Horn: I am, yeah.

MB: You haven't been back to the city in what, in how many weeks?

RH: Well I went up before this quarantine thing hit, which was mid-February. I came up here to work on some drawings. I'm thinking I better get them done soon because in May the show opens out in LA and fuck, I was worried because my hands are so screwed up, and I finished them before the quarantine.

MB: Excellent.

RH: I like this idea of imagining your physical reality, which is a vintage experience now. Do you know what I mean? It’s like the fact that you're actually somewhere—that’s already very abstract in today's dynamic. Everything's disembodied with regard to anything physical, including place and nature. The setting and all of that seems to be becoming irrelevant. I thought it would be nice to start with where we are physically in the world at this moment. I have this feeling that fills me with dread, the sense that meaning is shifting, this really basic meaning. Maybe not just shifting but disappearing. For me, it's happening because I don't have any confidence in the sources of information, I don't even have any confidence in who I'm dealing with in many situations. I feel that so much information is being put out there in real time, local and non-local information. If you go back a couple centuries, the big thing was to walk to your neighbors and tell a story or something. That level of physicality was closer to what I grew up with. Also, today knowing, in great detail, about things across the world—_as they happen—_versus not knowing what was going on in the next village for weeks. That kind of erosion of time and space is changing meaning completely. I feel very crowded in a way I never have because I've never limited my intake when it comes to what's going on in the world or culture. Now I feel like there's a leveling going on.

MB: Yes.

RH: I don't know how to use a critical facility to determine where is this information coming from? Is this valid? Certainly, in politics and history and all of these things—the doubt is coming so strong that it's eroding meaning for me. It's becoming so acute.

MB: Yeah.

RH: You have this endless demonstration going on with the President of nonsense– being purveyed as a thoughtful commentary, and it's being reinforced and validated by the politicians and by the media by showing it. Somehow the criticism or questions are never up to the content of what he's saying and the nihilism of what's really going on. It feels to me like there's no push back and whatever resistance there is, it doesn't have traction.

‘...the direct experience or the oral history of what's going on is far more meaningful and useful than what’s being reported.’—Matthew Barney

Photograph by Matthew Barney by his home in Sawtooth Valley; Photograph by Roni Horn in upstate New York

MB: I’m thinking about what you said about how important the news from the next village used to be, particularly in terms of where I am now in a remote area in central Idaho. Nobody seems to understand exactly what we're dealing with right now, and so somehow it can't be instrumentalized the way so many other things are in the media, even though it’s ubiquitous. There's no shortage of information about it, but none of it is definitive. So In fact, the person's experience on the other side of the mountain is as relevant as anything you hear on the news. I'm in a situation here in this county, for example, where there are no cases that I'm aware of, whereas over the mountain is one of these ski resort towns where they have one of the highest per capita rates of COVID-19. There are things to read about that but it's way more meaningful to talk to the people over in that county and get an understanding of what’s going on. In Boise, there was a rally the other day that was attended by members of the Bundy family and other separatist organizations protesting the shutting down of business in Idaho. My mother-in-law went grocery shopping later that day, and was verbally abused for wearing a mask and gloves by somebody left over from the rally. A fucked-up situation, but important information in terms of understanding the range of ways how Americans are dealing with this problem. There's that kind of leveling that seems to be happening, and that's what I thought you were talking about, that the direct experience or the oral history of what's going on is far more meaningful and useful than what’s being reported.

RH: Well for our generation it still is. That kind of experience is a quality of life issue really. I do mean that, but I'm also in this conceptual head space of ‘what does it mean when you collapse time and the energy so severely that things are just... like wallpaper’? It's the same everywhere you look. There's something coming at you of equal immediacy and scale, scale’s gone as well. Everything's an extreme situation, everything that's coming at you. There's no subtlety, the qualitative range of things is compressed as well. I feel that for me I base so much of my life and my work in the experiential realm and now I feel that my idea of the experiential realm includes dimensional space. It’s not a purely conceptual thing. It's in the physical world. This is where I feel like I'm having a hard time because I'm not interested in giving up nature and I feel like most of the younger generation is in effect giving up on it. They're in a way dreaming of going to other planets and that's another way of saying, ‘well this planet's fucked and we can't do anything about it so we're moving on.’ I'm not there yet. Are you? What's your feeling about nature?

MB: Like you, I need to be hands-on with it. I grew up around a fairly extreme version of it and so I think the suburban or countryside version of it that is available in and around New York City hasn’t worked for me when I’ve tried it... The ocean's a little foreign to me too. I think my nature's a little more of an inland mountainous one. That's the landscape that I feel most connected to, the vertical one.

RH: Is that because you grew up in a place like that…

‘I think of Iceland as big enough to get lost on and small enough to find yourself.’—Roni Horn

Roni Horn, Man in Hot Pot, 1991/94

MB: I think so. It's the thing that I really felt like I needed, since I moved to New York. The way I've set up my life and work, it's harder to afford the time to get back to that. I've tried to set up a situation here in Idaho where I can do it more often, which is important to me.

RH: It seems like in your last film you were definitely situating yourself in a very specific setting. I don't know about Sawtooth specifically, but definitely there was an idea of silence and of places that have a certain kind of open silence, the places that don't need language as much to communicate. There’s a sense that mountains are landlocked. I feel I go the other way to you, in that, even though I didn't really grow up with the ocean, I am drawn to it and I find my greatest peace near the ocean as opposed to the mountains.

MB: I know that you spent so many years in Iceland, and of course the water there is so present. It's been some years since you've been spending time there, hasn't it?

RH: Yeah unfortunately I've withdrawn a bit from it and I miss it terribly. Originally, I withdrew because it was becoming something more like the things I already knew, I didn't need Iceland in the same way. Part of this was tourism, but I miss the landscape a lot. To be honest, I even miss the culture to some extent although I could never live there. I still think of myself as a permanent tourist even though I'm not going as much.

MB: Has there been a shift since those years? Has that energy been put somewhere else?

RH: Well I think having this studio upstate has been part of it, although there's no ocean here. But now I'm thinking about spending time in Maine on the ocean and I think that will also provide me with some of that energy, but I don't think anything would replace Iceland. Because that island identity and so much of my identity is originating in a way from my experiences in Iceland. That is not going away, but my need to go there has shifted. I don't have the same need I did.

MB: There's the thing about an island that's as small as Iceland where you can account for all of it in your imagination. It's a small enough form that you can understand it as a land mass.

RH: Exactly. I think of Iceland as big enough to get lost on and small enough to find yourself.

MB: I was thinking about how your place in Maine, it's kind of a... What's the word called? The little thing that sticks out into the water?

RH: Peninsula.

MB: It's a peninsula, isn't it?

RH: You could call it a finger, babe. But it's a little peninsula, yeah.

MB: It's a little peninsula, so it has a more understandable form, which is interesting.

RH: Yeah, that makes sense what you're saying.

MB: It also has the violence that the ocean has up there.

RH: Yeah in certain parts of Maine it's very similar to Iceland. My location's a little bit more protected, it's more like a bay area. I think I'm drawn so much to the weather, even now. I mean, it blows my mind what's going on up here where I am now, in this pastoral setting, which on one level gets on my nerves and on another level, I feel like I'm seeing things I've never seen before often. Whether it's what animals are doing with the weather or what the weather is doing in the form of the wind and the temperature gradients. What you sent me the other day with the ice coming off the roof in curls, that was so beautiful. I couldn't believe it. It still must be cold out there huh?

MB: Yeah, it's still cold. The snow is melting off a little bit everyday but it's still very cold, and it remains cold throughout the year. You'll have days here in the summer, in August where it's below freezing at night and then 85 degrees during the day. The differential temperature here is extreme.

RH: But you're high up, right? How high?

MB: 6,500 feet.

RH: Yeah, because that's high... I know that when I would go down to southern Texas, which was 7000 feet up or so, it had that kind of... extreme. You'd go down to the 40s at night and you'd go up into the 90s during the day. it would really get quite hot. Quite beautiful I think and I like that. It meant that I was out more at night than during the day.

MB: Yeah, there's something about the Sawtooth Valley that it's often one of the colder places in the country, at least in the lower 48. I think it has to do with the topography and how extreme the high and low elevations are and how close they are together. It functions something like a heat sink does where the landscape has this dynamic range of surface area holding pressure and temperature. You'll get these extremely low temperatures here. It's not uncommon to feel 30 or 40 below zero in the mornings in the winter and yet it'll come up above freezing often on the same day. It keeps this place pretty unpopulated, which is great.

RH: I love that. Are you spending a lot of time in that freezing cold or do you tend to wait for it to get a little warmer?

MB: I'm coming out whenever I can. I suppose I spend a little more time here in the warmer months, but we did all that filming for Redoubt out here in the winter and I've been coming here each winter since I've had this place. Another thing I like about your idea to describe the view from the window is that while I've known about your place upstate for many years now, I've never been there. I've known about your place long enough that I have a picture in my mind of what it's like and—

RH: So tell me about it.

MB: —It's probably nothing like it is. I know that there's a body of water, there's a canoe. I know that it's densely wooded. I have a fairly good picture in my mind of that lake. But now I’m seeing your picture now on the Zoom screen and trying to imagine what that structure is like from the outside that you’re standing in. Already that doesn't fit with the image in my mind.

RH: Imagination is a good thing to correct for all the qualities of the world. I remember that conversation we had about the canoe because I remember you asked me, ‘can you disappear on the lake in the canoe or get lost?’ I can't remember what word you used, and that was a great way to visualize the scale of the lake because it doesn't give you that option.

MB: Yeah.

RH: I guess that's why you never came, huh?

MB: Right, I wanted to get lost.

RH: What a great privilege to get lost these days.

Matthew Barney, still from ‘Redoubt’ shot in the Sawtooth Mountain range of Central Idaho, 2019 © Matthew Barney. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, and Sadie Coles HQ, London

Matthew Barney, production still from ‘Redoubt’, 2019 © Matthew Barney. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, and Sadie Coles HQ, London

MB: Yes, truly. Now I'm thinking of your book, My Oz... When you first sent me that book, I was wondering ‘what is that place for myself where I've never been but have a fully realized view of in my imagination? A place where I never want to go because I don't want to lose that sense of what my imagined reality of that place is?’ I think, weirdly, it's Alaska. I say weird because it's probably a more extreme version of where I am right now in Idaho. I think there would probably be a real familiarity with that landscape if I were to go, but yet it exists in my imagination in a way I wouldn't want to disrupt.

RH: Yeah, yeah. It was Patricia Highsmith, the mystery writer, who was always complaining about how if you live with somebody they ruin your imagination so she was always defending her desire to be alone because then nobody was impinging on her imagination. I think this is actually partly my feeling too, that loss of meaning, coming that way. Through the constant impingement on imagination in the form of overpopulation in effect. Now this whole pandemic thing is really about overpopulation. The fact that one country could do something with their food chain and it gets spread all throughout the world. It's really about too many rats in the can now to survive, and we’re really all at the mercy of each other's judgments and intelligence and that is not a good place to be. Too vulnerable. Also, you see the way this idea of the common good is being lost. Is it the common good of my local community or of the country, of the planet? Ultimately it's the planet, but I don't think that's working for anybody. I feel like nationalism is intercepting that possibility. I guess what does it mean to know something in the actual time it's happening? You know, 1,000 miles away. I mean that's a very different form of knowledge than standing in front of a fire. Do you have a fire out there a lot? Every night? Or how do you work with fire out there?

MB: Yep, every night, every morning. Yeah, it effectively heats the house.

RH: Yeah. You have a word burning stove?

MB: Yes. What do you have there?

RH: Up here we have a fireplace and the floor is heated. Up in Maine it'll be a wood burning stove.

MB: Yeah, it's a good ritual to start the day. It is.

RH: Yeah, starting a little fire.

MB: Yeah, there are forest fires here in the summer of course and in August especially. There's usually a couple fires burning in this area at any point in the summer.

RH: Wildfires or-

MB: Wildfires from lightning and sometimes, negligence. Yeah. Now they call it August fire season. It's a new reality here.

RH: So that hasn't always been that way.

MB: There have certainly been fires here over the years, but I think the frequency is new. The regularity and the frequency.

RH: I was just thinking about the situation in Australia where it got so hot that things just caught fire from the heat.

MB: Spontaneously combusted.

RH: Yes, and I thought that is a serious metaphor for what's going on now. It's like you don't have to do anything because we’ve prepped the scene to do it on its own.

‘I've been thinking about how there's this incredible opportunity right now to observe what happens when everything shuts down. In terms of the environment, and I'm also a little bit surprised that it isn't at the top of the headline. Why are those not the photographs that we're looking at right now?’— Matthew Barney

Matthew Barney, still from ‘Redoubt’, 2019 © Matthew Barney. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, and Sadie Coles HQ, London

Matthew Barney, Elk Creek Burn, 2018 © Matthew Barney. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, and Sadie Coles HQ, London

RH: Do you think much about the climate and what's going on in that way? I mean we don't have to talk about this but I was curious to know if that affects you at all, your daily life or your mental state.

MB: I've been thinking about how there's this incredible opportunity right now to observe what happens when everything shuts down. In terms of the environment, and I'm also a little bit surprised that it isn't at the top of the headline. Why are those not the photographs that we're looking at right now? So yeah, that has definitely been on my mind. I'm really eager to know whether it can even be quantified and how quickly the environment can rebound. It's something I feel like you would never usually be able to know, because there's generally a refusal to shut down. People will not turn it off, they won't. I want to know what effects this [current situation] is having.

RH: I'm with you.

MB: If it's quantifiable, I'm bewildered why I can't see more evidence of it. I was in Beijing last year during their celebration for the 70 year anniversary of the People's Republic of China, and during the rehearsals leading up to the celebration they turned off all the factories.

RH: Clear the air.

MB: The skies went clear so quickly it was incredible. Having spent a little bit of time in Beijing, you can't imagine that air quality could ever be clean. It seemed so toxic there. In fact, it did recover and became clear quite quickly. We've seen that with the cleanup of the Hudson River to a certain extent, and that happened in a much quicker way than people expected. I think some of these systems can repair quite quickly, if given the chance.

RH: Are people able to fish in the Hudson now? I think a lot of that fish is still considered toxic, isn't it?

MB: I'm not sure about that.

RH: The PVCs or is it PCBs? They went deep into the mud, they say.

MB: Right. On the banks and in the inlets, especially. It’s like that in the East River where my studio is. The inlets and New Town Creek are still a mess, but out in the middle where the current is strong enough to flush the crap out it’s getting cleaner.

RH: Yeah, nature is a living force so things evolve quickly there as far as cleaning the system out. The evidence I have is the air quality index and the daily weather reports, which is going way down, which is great. For me that's been a very positive thing about this COVID-19 situation, but you don't feel like people are learning that lesson. As you said, they're not paying attention to the idea of, okay, as soon as social distancing ends is this going to be people running all over the planet to see their friends for a couple days. You know what I mean? This kind of hyper-consumption, which is mindless for the most part.

MB: Agreed. One of the ideas at the center of the discussion around the reintroduction of wolves in Wyoming and central Idaho is the trophic cascade. What happens when you take the apex predator out of the picture in an ecosystem and how that then brings the elk herds lower, they eat more and deplete the foliage around the lakes and rivers, that foliage in turn is the food of smaller mammals. It keeps working its way down.

RH: Yeah, the balance... Any one thing affects a myriad of things, and that's what you start to see now, as things move out of balance.

MB: Right, but there's a tendency to think, okay, you bring the apex predator back into that ecosystem and they breed and proliferate pretty quickly, and they start to have a positive effect on that environment. But in fact there are damages that were done in the process that are irreversible. So I guess the thing that's a little dangerous is to think that there is a quick fix for the problem.

RH: Well the illusion of going back is just that, it's never more than an illusion, it's a desire, it's a wish, but it's not an option.

MB: It's not an option.

RH: So not an option. The air may be cleared, but the carbon that’s already been dispersed is not going away so quickly. I always wind up talking myself into silence.

MB: Thanks. I like it.

RH: You're probably drawing in the house there. What's outside the window? Or do you work in the closet? I can see you down in the boiler room or something.

MB: It's kind of a laundry room.

RH: I love that. I love your little desk. With me, it would probably be a little computer and I'd be writing in the middle of the night down in the basement.

MB: Maybe I should tell you what’s outside my window now? The view is to the south, and I see the Sawtooth range and the Sawtooth Valley. The Sawtooths are to the right of my view and to the left are the White Clouds. The difference between those two mountain ranges is pretty interesting. The White Clouds are subtle, they have these large mineral deposits on them that leave these whitened slopes. They're wooded but they're soft compared to the Sawtooths. The Sawtooths have sharp granite peaks, so they look a little like the Tetons. The source of the Salmon River is at the southern end of the valley and it flows along the base of the Sawtooths.

RH: The White Clouds, are they older? More eroded than the Sawtooth?

MB: I don't know if they're older, but that seems logical... But the Sawtooths have this kind of presence. They’re more autonomous. The way that light plays off of the granite, on those mountains, and gives them an articulate form. They have an object-like character in the way that the White Clouds don't, and I think that that has something to do with what we were talking about with the peninsula or the island. I have a relationship to these mountains that I've had since I was a kid, and I think it's to do with their objectness.

RH: What's the sky like there? Is it very high?

MB: One thing that's remarkable here is the clarity of the sky. Although there's a lot of snow in the winter, there's not a lot of precipitation in the warmer months, and so the air is very dry and clear. Between that and between the fact that it's quite isolated and there are no city lights anywhere near here, it's a dark sky corridor where you can really see what's going on up there.

RH: Wow.

MB: It’s exciting.

Roni Horn, Air Burial (Invercauld, Cairngorms National Park, Scotland), 2014 - 2017 © Roni Horn. Photo: Michael Wolchover

RH: Yeah. When you go down to New Mexico, it has this vastness, the sky has this vastness and it feels like it's higher up and there's more of it every time you look. I've not had that experience anywhere else. I associated it with the west but I think it's more to do with not having a lot of mountains and vegetation around as well. Also the weather seems to be happening almost higher up. You could see miles to somebody else's weather. The lightning striking somewhere else or the rain coming down somewhere else. You're sitting in the sunshine minding your own business and it's... Actually, I had that experience a lot in Iceland when I stayed in that lighthouse in the early 80s. You could look south and see the weather coming up the coast, usually a lot of rain because as it was getting warmer, the weather was coming in to meet the cold weather and there was precipitation. When you would look north, it was always a lot clearer, you could see further and there was a little less action somehow. It was an interesting thing to associate weather with motion, with distance. I grew up with weather, it was either over my head or there was nothing. That idea of seeing far into the atmosphere, because of the quality of the landscape, is very deeply affecting to me. You do get that in New Mexico, that was the first time I was really aware how high that fucking sky was and how articulated the clouds were. There wasn't much wind so things weren't getting dispersed so quickly. Things were really getting into these baroque shapes and really elaborate cloud details that you don’t get in a more windy setting. You know what I mean? MB: Yes. I was really surprised the first time I went to Montana because I thought that I understood the general landscape in this area having grown up in Idaho, and when I went to Montana I realized it was very different. The valleys were wider, the mountains were larger, it's like the whole proscenium is larger. The sky is truly bigger there and I didn't think that was possible. RH: I had a big surprise first time I was in Montana with my girlfriend. I got kicked out of the hotel when they figured out I wasn't a guy. That was a shocker. MB: Jesus.

RH: A lot of religion up there and who the hell knew, man.

MB: Yeah, exactly.

RH: I let people think what they want and then when they decide what they decide, either I'm fucked or I'm not. Literally got kicked out the fucking hotel. I never experienced anything like that.

MB: Which town was it?

RH: I was south of... Oh God. I was on the border with Wyoming because there were hot springs there. It was an old hotel which had a relationship to hot springs so that at night you could go swimming in these hot springs. It wasn't natural, they had developed it into a pool area so people were there, it wasn't really a spa but it was a tradition there. Southern Montana and it's between... I'm trying to think. What are the three, Missoula…

MB: Missoula, Billings, Helena.

RH: Billings, south of Billings.

MB: Yeah I could remember so much coming to New York City first as a teenager and seeing how the sky is framed in Manhattan and found a lot of affinity for that view, much in the way that the ravines in central Idaho are quite narrow and they frame the sky. You definitely have a similar experience with both landscapes as being vertical and having that same kind of pressure, and also the relationship to the movement of the sun and how there's no sunlight in the afternoon, it's only reflected light.

RH: They're in shadow, yeah.

MB: You're in shadow, yeah.

‘That's the kind of the monument I like, the one you sense and feel, but you don't have it in your face.’—Roni Horn

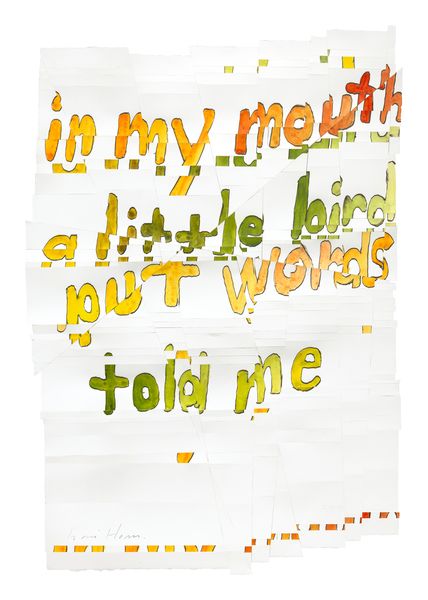

Roni Horn, Hack Wit - bird words, v. 2, 2014 © Roni Horn

RH: It's a funny thing what you're talking about, because I can relate to that through Iceland. I have this theory of why I became so attached to Iceland, which is probably complete bullshit but I like it. The cloud cover was always sitting on the ground or very close to the ground, and every time I'd go, I’d see a different bit of the same place and never saw the whole thing. This idea of going back to a place that you can't really see when you're there fascinates me. That's changed a lot now because it's dried out a lot, so you don't have clouds quite as steadily as you did. Well as I remember them in the late 70s, early 80s, mid-80s. You knew there was something unbelievable if you just endured. Of course, I was coming and going so I was at the mercy of not being there all the time, so I had to take what I could get. I never got the whole thing and that was part of the beauty for me. You probably have something monumental there but you'd never know it. That's the kind of the monument I like, the one you sense and feel, but you don't have it in your face. I think that what you're describing is really an idea of the majestic and something quite awesome really, just the scale of it all. The energy that comes out of all that verticality, it is what it is. I don't have that experience really in Iceland.

MB: I was just thinking about how I've probably been to Snæfellsnes 10 times and I think last year I saw it for the first time.

RH: Right, exactly because there's always that cloud sitting on top.

MB: Exactly, yes.

RH: I love that. But that's that imagination thing. You’ve got to be satisfied with what you can conjure up. But I’ve got to tell you—when you do see things—it blows your mind too.

MB: Yes.

RH: I have this fantasy of where I'd like to be pretty much all the time, and it's got nothing to do with anything practical, but there's this place in southeastern Iceland and it's more about the spiritual energy of the place and I always want to go there. It's my hotspot. It's the beauty of everything there. Most people would find it sparse and ascetic, but there’s a beauty and simplicity to it. It's transparent in its simplicity.

‘I always think of it as an opera. When I'm listening to the owls I'm thinking there's got to be some narrative I'm missing here. It's so exquisite and I love that it's all in the dark.’—Roni Horn

MB: So what's outside your window?

RH: Depends on when, but there is that lake that you cannot get lost on. A lot of birch trees, white birch, really delicate clumps of birch. They're very erotic and they're very tender and vulnerable. Then a lot of bird life. I've never sought birds out, but I've wound up in amazing settings where birds were really the main action. I was working on this thing I told you a little bit about. It's a log book over a period of years. It's not a book but a log, a near daily log for the last year. There's a lot of impromptu writing in there and some that I've worked on. What was weird was, after I pulled out all this material, there were a dozen short anecdotes, a page long and not more, of different interactions I had with birds over the years. Personal interactions. I'm not talking about you coming and visiting me as the crow, but I mean this bird is looking at me, and I’m looking at it—with owls and egrets, really amazing things. I have to say that has been something that came to me unbidden and then became part of my life really. It was frozen and it was snowing, so you couldn't really see far, but I could see there was a black turkey that somehow wandered out onto the lake, a wild turkey. I could tell she was kind of lost because everything was so bright and she couldn't figure out where she was going. She was walking in these circles on the lake thinking she was going somewhere, and it was sort of sad watching her. It was so bright and everything was covered in snow. I think she lost her orientation. Just the idea that I witnessed that made me feel like Emily Dickinson. The way she sees the most mundane natural event.

Roni Horn, Dead Owl, 1997 © Roni Horn

MB: That's beautiful. Here, there are these Sandhill Cranes that are breeding this time of year and they come onto the property in the morning.

RH: Oh wow.

MB: The voice is incredible. It's one of the things that really gives you a sense of how sound works in this landscape. You can hear them from a great distance away. Granted they are loud, but they are so present even if they're so far away. Particularly this time of year with the snow insulating sound and the way that the mountain walls create an acoustic, it’s really special.

RH: What is it? The crane, the sound of the crane. Can you relate it to anything I might know? Is it like a goose honking or what is the sound?

MB: I mean it's longer than a honk and it has more gravel in it. It's a more sustained tone and it's deep. Yeah, I think when you first hear the Sandhill Cranes you don't necessarily associate it with a bird, which is interesting.

RH: It's funny you say that because I have an experience of the night here in the summer especially, you get these Barred Owls, which are large owls and they're very articulate at night. It's not just like one sound or a basic rhythm. You never see them but you hear them and it sounds like something quite theatrical is going on. It's the opposite of what I associated with bird calls. It feels like there's nothing repetitive. I mean there is if you listen long enough, but it feels like there are many owls participating in this dynamic. I always think of it as an opera. When I'm listening to the owls I'm thinking there's got to be some narrative I'm missing here. It's so exquisite and I love that it's all in the dark. Also the thing about darkness, and you probably have incredible experiences out there in the mountains, but I remember when I was working on ‘Library of Water’, collecting the ice, we had to consider the weather. It had to be frozen otherwise you couldn't drive in a lot of these areas. We were up in the north, northwest and I remember a night of driving where the sky was totally illuminated by the aurora borealis and it went on for hours. You'd keep driving north and it was almost like you were expecting daylight. It was so bright. Then it would reflect off the snow so it was this very theatrical presence. I'm going to sign off now. Take care babe.

MB: Bye, Roni.