Conversations

Bibliotheca Hermetica: Mario Diacono and the arts of alchemy

By Bob Nickas

‘The Seven Days of Creation,’ from Gregorius Anglus Sallwig’ts (Georg von Welling) Opus Mago-Cabalisticum et Theologicum (Frankfurt, Germany, 1719). Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

- 2 March 2020

Poet, essayist and gallerist Mario Diacono, on the cusp of his 90th year, has led one of the most unusual lives in postwar contemporary art, beginning with his first gallery in Bologna in 1978, where he showed Arte Povera artists like Jannis Kounellis and Pier Paolo Calzolari. In the 1980s in Rome, he became involved in the revival of painting, showing the work of many important Neo-Expressionist artists, and he later opened spaces in New York and Boston.

In 2007, with the closing of his final gallery in Boston, he became more fully involved in the Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia, the private museum opened that year by the family behind the Max Mara fashion company, a collection he has helped shape for more than 30 years. But throughout much of his life in contemporary art, Diacono has led an extraordinary parallel existence rooted in the distant past, as one of the world’s foremost collectors of books and manuscripts devoted to alchemy and occult philosophy. The following are edited excerpts of a recent conversation between Diacono and the curator Bob Nickas, conducted in Boston, where his library resides.

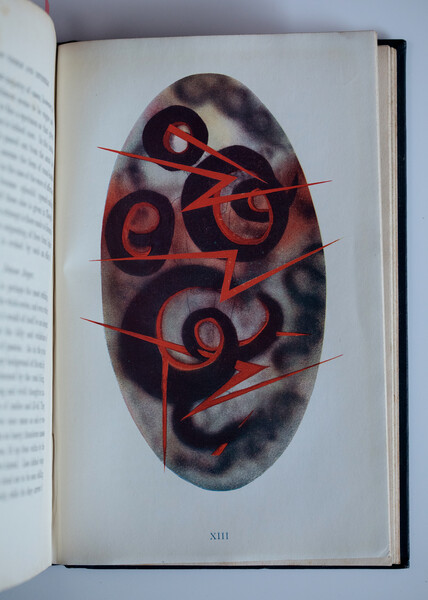

‘The Rebis (Androgynous,)’ from Salomon Trismosin’s Aureaum Vellus (Rorshach am Bodensee, Germany, 1598-99). Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

Bob Nickas: We’ve been friends for more than 30 years now, and I’ve known that you collected books on alchemy and how foundational they’ve been for your mind, but until you recently published a catalog of them, I didn’t realize the extent of this fantastic collection. Among 126 books, the earliest is from 1523, and there are many rare titles—one I recognized right away, Daniel Defoe’s ‘A System of Magick;’ or, a ‘History of the Black Art’—and another with a particularly resonant provenance, ‘Essais de Sciences Maudites,’ by Stanislas de Guaita, which came from the library of André Breton, author of ‘Surrealist Manifesto.’ How did your interest in alchemy come about?

Mario Diacono: When I was 20 years old, in June of 1950, I ran away from home, from Rome, and went to Venice with the romantic idea of embarking on a ship sailing for India. That didn’t happen because, once at the port, I was asked if I had a card showing I was a member of the maritime union, but I had never set foot on a boat before. In any case, first of all, I wanted to see the Venice Biennale, and I don’t know how, but I managed to get into the press preview. There, I heard about the exhibition of an avant-garde American painter, and I soon found myself in the Jackson Pollock show at the Museo Correr, I think: it was ‘bouleversante,’ as the French would say.

Gian Enzo Sperone, Francesco Clemente and Mario Diacono, Rome, 1980

Diacono reading Erving Goffman’s ‘The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life,’ a book that Vito Acconci told him was important for his work, 1972

BN: Overwhelming.

MD: Yes, and to this day it remains the most memorable exhibition I have ever seen. Anyway, having remained unmoored in Venice, I started to spend my mornings in the Marciana Library. At that time, before entering the main reading room, you would pass a row of vitrines in which were exhibited some of the library’s most spectacular possessions. Among them was a Greek manuscript from the 10th century, open at a double page with two highly enigmatic images, the Ouroboros and the Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra.

BN: Not to be confused with the queen of Egypt, but Cleopatra the alchemist, one of the few women involved in the practice, and of course the Ouroboros is the snake eating its own tail.

MD: For some weeks, every morning I was stopping in front of these images, interrogating their meaning. When, in 1964, I found in the window of a Roman antiquarian bookseller a 1925 Italian book titled ‘On the Historical Sources of Chemistry’ and ‘Alchemy in Italy,’ and a short time later a friend, Emilio Villa, pointed me to the Italian translation of Jung’s ‘Psychology’ and ‘Alchemy,’ that Venetian interrogation kept coming back incessantly.

BN: And this obsession, if I can call it that, led to your collecting these books?

MD: More than an obsession, it was an unstoppable investigation. But I didn’t start to buy original hermetic/alchemical early editions ‘cum figuris’ until I had some real money of my own.

BN: ‘Cum figuris’—with illustrations?

MD: Yes. I began to buy these books with the money I had earned teaching 20th-century Italian literature at U.C. Berkeley from 1968 to 1970.

‘Nothing is more rewarding than going through a museum on acid. The artworks, especially Chinese and Japanese scrolls, come alive, become fluid—you enter them and become part of the representation.’ —Mario Diacono

BN: You were there in a very heady time. The Free Speech Movement had spurred a real engagement with protest, particularly against the war in Vietnam. Reagan, who was then governor of California, was hell-bent on crushing the student movement. You told me once about a demonstration for People’s Park, when you and a young friend were warned by a National Guard to leave or else you’d end up being arrested. The Guard had been ordered to surround the demonstrators so the police could arrest everyone.

MD: Soon after we left, hundreds of students were arrested and had to spend the night lying on the ground of the parking lot of the police station. ‘The Fascist Gun in the West’: that’s what Reagan dressed as a cowboy was called on posters put up all over San Francisco.

BN: How do you remember your time at Berkeley—politically, socially? And who do you remember from there?

MD: I was aware of the Free Speech Movement before I went to Berkeley. Actually, that was the very reason why I chose this university over others. Politically, I was following from a distance the activity on campus of my favored groups, the Students for a Democratic Society and the Black Panthers. Socially, I started doing what my students were doing, smoking pot in the evening and taking acid on Sunday morning.

BN: Mario! I didn’t know that. Going to high mass on Sunday!

Illustration from Charles W. Leadbeater’s ‘Man Visible and Invisible’ (London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1907). Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

MD: Art-wise, I met Ronald Kitaj a few times, who was teaching there and whom I interviewed for the Italian magazine ‘Collage.’ I was impressed by the films of Bruce Conner, and I visited regularly the exhibitions of San Francisco’s galleries. Besides the time spent in the library for my graduate-student classes, I went to all the anti-Vietnam demonstrations—‘U.S. out of South-East Asia! ROTC must go!’—and almost every week to a Fillmore West concert. The most unforgettable one was Jim Morrison. Every Sunday I visited one of the museums in San Francisco. Nothing is more rewarding than going through a museum on acid. The artworks, especially Chinese and Japanese scrolls, come alive, become fluid—you enter them and become part of the representation. It’s not exactly 3-D, but you may call it an LSD vision. Really, it was the entire social, political, musical environment that I soaked up for almost three years there that caused in me a sort of ‘biosophical’ rebirth. Nothing has been the same for me after Berkeley.

BN: I know you well as a word-breaker/word-maker. ‘Biosophical.’ You were thus equally and at the same time reborn biologically as well as philosophically. Back then, were you already wearing the many amulets that you always have strung about your neck? Anyone meeting you, even for the first time, can see that there is occult knowledge about your very person.

MD: I started wearing them when I was in Berkeley, probably influenced by the hippie syndrome, but ‘occult knowledge’ is too strong a term. I am a son of the Enlightenment. At the time of the Enlightenment, having esoteric knowledge was not a contradiction. I have never been part of any occult practice. I’ve only been deeply interested in European esoteric iconography and thinking, just as I have been in prehistoric, tribal, Indian and Tibetan Tantric iconography—in the sacred/secret side of history. The amulets I am wearing are in gold, silver, bronze and iron. I carry them as symbols of the ages of Man.

BN: When did you go back to Rome from the U.S.?

MD: In the summer of 1970. As soon as I was back, I began to visit antiquarian booksellers and bought my first book of magic/alchemy. This was the first of the two volumes of the circa-1580 edition of Cornelius Agrippa’s complete works, published in Lyon, which contains his ‘De Occulta Philosophia Libri Tres,’ published in 1531, of which I have two copies, and also includes the first edition of the apocryphal fourth book titled ‘De Caeremoniis Magicis.’

BN: Who was collecting books like these at the time, and how expensive were they? Also, you once told me that you only started a gallery to make money to build your library of rare books. I half believe you.

MD: That’s half, or even a quarter, of the truth. After Berkeley, I started to collect at the same time early editions of alchemical/hermetic books and first editions of 20th century avant-garde books. Of the latter, I mostly collected Futurist, Surrealist and Bauhaus first editions, buying more in depth the works of Marinetti, Antonin Artaud, Duchamp. This collection I sold in 2000 to Ars Libri, when I decided to close my gallery in Boston, concentrating afterward on the alchemy books, which were becoming rarer and rarer and more and more expensive. When I started buying them, I didn’t know anyone who was also collecting them, except my friends, the former gallerist Arturo Schwarz and the artist Claudio Parmiggiani. With Parmiggiani, we were running all over Italy in his car to check out as many antiquarian booksellers as we could find. Around 1990, I learned from a London bookseller that Umberto Eco was also collecting these books, but except for meeting him a few times, I can’t say we had a friendship.

BN: Your mention of Eco reminds me to ask, going back in your story for a moment, about your relationship with an important literary figure when you were younger, the poet, provocateur and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, although his movies came later. I believe he helped to publish your first poems. When was this?

MD: I was friendly with Pasolini from 1955 to 1958. In 1954 I had published a review of an anthology of contemporary Italian poetry, singling him out as the strongest voice of the new generation. On the basis of this, I was introduced to him by another poet, Sandro Penna, to whom I had been close for quite some time. Penna and Pasolini used to scour the Roman suburbs together, and out of both curiosity and friendship, I followed them a few times. I began to visit Pasolini at his home to discuss his poetry, and in 1956 he proposed my poems to a magazine editor with whom he was very friendly. So he was instrumental in the publication of my early poems in the magazine ‘Galleria.’ Our relation unfortunately ended when I wrote, in 1958, a review that was critical of the magazine ‘Officina,’ of which he was co-editor. We simply stopped talking after that. At the same time, my literary interests were moving in a direction radically different from those of his circle, even if I had always recognized him as the preeminent poet of the 1950s, out of which I also came.

‘The man in charge of scientific books at Quaritch, who had become friendly with me after I had bought other books from him, told me: ‘If you don’t buy it now, I will sell it to Umberto Eco.’—Diacono

BN: This shift in literary interests was certainly clear—and maybe foreshadows your interest in art—a decade later, in San Francisco, when you published the chapbook ‘JCT,’ based on Mallarmé’s poem ‘Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance).’ You interpreted this as purely visual typography, the words having been completely dispensed with. Although the book is dated 1968, the precise date of printing is November 1969. This has such direct correspondence with Marcel Broodthaers’ visual interpretation of the same poem by Mallarmé, which he published that very same month and year in Cologne. What are the chances of that! These two books produced simultaneously a world apart.

On your title page there’s a bit of wordplay I’ve never asked about: ‘a METRICA n’aboo lira.’ The capital T in METRICA is printed in orange, while the rest of the letters are black, so there’s a play between metrics, or poetry, and America. Since you were in a radical environment, Berkeley, at a radical time, 1968, were you suggesting that something has been abolished in America? I’m also reminded in this of the filmed interpretation of the poem by Straub and Huillet, ‘Every Revolution Is a Throw of the Dice.’

MD: 1968 was a year in which many things were abolished, or felt tempted to be abolished. Language was one of them, at least the traditional language of poetry, but also the language of ‘bourgeois/capitalist’ society. Berkeley is also present in the book through the reproduction of three frames from a cartoon in a local magazine, which functions as a kind of preface. The title alternates not only colors, black and orange, but also uppercase and lowercase letters. The wordplay in essence says: the absence of metrics, of language, will not abolish poetry. Neither will the American taboos. As for the gap between the year of composition and that of publication, it was due to the lack of funds. All my books of poetry have been self-financed, so I needed time to put together the money to publish it, because I was also buying books. In 1968, with my first salary from U.C. Berkeley, I had bought in San Francisco one of the 110 copies of Robert Lebel’s ‘Sur Marcel Duchamp.’

BN: You say nothing was the same for you after Berkeley, and it’s clear that between 1958 and 1970, you were transformed, or to use an alchemical term, there was a transmutation. Back in Italy in 1976, after teaching for four years at Sarah Lawrence College and writing a book on Vito Acconci, you opened a gallery and more avidly continued collecting books on alchemy. With your first gallery in Bologna, who did you show? I ask because a number of the artists associated with Arte Povera, most of whom you knew early on, created works that some have seen in connection to alchemy.

MD: I opened the gallery in January 1978 with a single ‘painting’ by Jannis Kounellis. In my second exhibition, there were two sculptures by Parmiggiani. The third was a group show titled ‘Per una politica della forma’ (For a Politics of Form), which included Pier Paolo Calzolari, Jannis Kounellis and Mario Merz, with a single work by each. In this show, Merz’s piece was ‘Nove Verdure’ (Nine Vegetables), for which every week I had to go to a market and buy fresh vegetables to replace the ones that had begun to spoil. Of the Arte Povera artists, besides Parmiggiani, as far as I knew then, only Zorio was interested in alchemy, and I never had a chance to show him.

BN: Among the books you collected in the late ’70s, which are the most rare, and do you remember about what you paid for them? This, of course, is a lead-in to my asking, what’s the most expensive book you ever bought?

MD: The most important book I bought in the ’70s was Khunrath’s ‘Amphitheatrum Sapientiae Aeternae,’ from 1609, which I acquired in Rome in 1973 for 500,000 Lira—about 3,700 Euros today. On this book, by the way, Umberto Eco published an excellent bio-bibliographical essay in 1989, ‘Lo strano caso della Hanau 1609,’ which became widely known after its 1990 French translation, ‘L’énigme de la Hanau 1609.’ The most expensive has been Salomon Trismosin’s ‘Aureum Vellus,’ 1598-99, bought from Bernard Quaritch booksellers in London, I think in 1992, for 20,000 pounds, which I got by selling to Achille Maramotti, for exactly that amount, a group of Acconci drawings that Vito had given to me for having done his show in Bologna in June 1978. The man in charge of scientific books at Quaritch, who had become friendly with me after I had bought other books from him, told me: ‘If you don’t buy it now, I will sell it to Umberto Eco.’

Incantation bowl, Mesopotamia, sixth century. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

BN: What is it about alchemy, esoteric knowledge and magic that fascinates you particularly? Do you see it relating to your interest in contemporary art, and how has it informed your writing on art? Among gallery owners, you are the only one I know who wrote an essay for every exhibition presented over 30 years. Of all you have absorbed from the books in your collection, and of course much of this information is visual, what have you brought to bear on the art from the ’70s until today? These books, which have been in the world for centuries, and are in your hands in the here and now, suggest to me nothing less than a form of time travel.

MD: Yes, it was for me a form of ‘possessing the past.’ I consider alchemy—the alchemy practiced in Europe from the late Middle Ages to the late 18th century, the humanistic Europe—a post-Christian mystery religion that disappeared at the birth of the modern world, which we can date to the 1789 French Revolution. The transmutation of lead into gold was not that dissimilar, as a process of secrecy and meaning, from the rebirth of the acorn in the Eleusinian mysteries. We can never be totally sure if it happened or not. This mysteric element is fascinating. A process aiming at a ‘perfectioning’ of matter, at a transmutation of one matter into another, implied a coupling of magical thinking with technical thinking, implied a vision of the world alien to any scientific explanation. Alchemy was an interrogation for which the manuscripts and books we are left with attempted an answer. The answer was different from book to book. The difference becomes immediately evident in the images present in all of my books. They are different from one another, just as works of art are. In a hermetic book, the author of the images is not materially the author of the text. The images are almost always not an illustration but an interpretation of the text. So, over about 500 years, you can see an evolution of the alchemical image that is coexistent with the evolution of art. The essence of the alchemical image is that it is most often symbolic. It’s this quality that is supremely intriguing to me. And it’s exhilarating when I find this quality implicit or explicit in artworks, both ancient and contemporary.

BN: With the return of figurative painting in the late ’70s, early ’80s, when you began to engage with artists through exhibitions, did these qualities at times appear in what you chose to show? The artist who comes immediately to mind, although I know you wrote about his work only in ’89, is Sigmar Polke. With your second gallery, in Rome in the early ’80s, who were you showing? And were you able to build your library more readily in this period? I ask this knowing that of the 126 books you assembled, only a dozen came from antiquarian shops in Rome. I assume you found many of the books in your travels, and I imagine some, on occasion, were bought at auction.

Diacono in his Boston home, September 2019. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos

MD: To answer the first part of your question, I almost cringe every time I see the notion of alchemy associated with contemporary art. They are two incommensurable entities. Alchemy was a religious metallurgy, a philosophy-inspired technique, an investigation of matter, which cannot be related to any contemporary typology of chemical manipulations. In Polke’s paintings, for instance, there may be an enactment of chemical and technical procedures that involves more imagination than science, but there are no actual or factual connections to historical alchemy. I may have occasionally resorted in my writing on artists to the language and the concepts of alchemy as mythical references, but I never intended to make a direct claim of comparable status. Alchemy in contemporary art can be referenced as a foundational myth but in no way appropriated as a model or even an archetype. I remain anchored to the conceptual distinction I made in the 1950s between the images of the codex Marcianus Graecus 299 in the Marciana Library and Pollock’s painting ‘Alchemy’ in the Guggenheim collection. In my Bologna gallery [1978–79], I mostly showed Arte Povera artists, while in my Roman gallery [1980–84], I mostly showed Neo-Expressionist painters: Sandro Chia, Enzo Cucchi, Francesco Clemente, Mimmo Paladino, Nicola De Maria, Bruno Ceccobelli, Basquiat, Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Eric Fischl. I would say, however, that the strongest part of my collection was built while in the United States. As you mentioned, having an art gallery at a time when there were impassioned collectors did provide me with funds that I would not otherwise have been able to earn as a college professor at the time.

BN: Although there are only about 20 books in your collection published in, and just on the cusp of, the 20th century, there are a number of standouts, maybe because the authors are more recognizable to those of us who are not exactly initiates, but also because of the subject matter. Erik Satie’s ‘Sonneries de la Rose + Croix’ [1892]; two Charles Leadbeater books, one on clairvoyance, ‘Man Visible and Invisible’ [1907], and ‘The Chakras’ [1927]; Aleister Crowley’s ‘The Equinox’ [1910]; Jung’s ‘Psychologie und Alchemie’ [1944]; and, last but not least, P.B. Randolph’s ‘Magia Sexualis’ [1931]. Did you see your collection coming to a conclusion as the books approached our time? In a sense, in terms of your recoil from relating alchemy to contemporary art, maybe there can be no further evolution, as you mentioned a moment ago, of the alchemical image, because in our time, the books can be only studies of the studies of the subject.

Diacono with Michael Maier’s ‘Symbola aureae mensae duodecim nationum’ (Frankfurt: Lucae Iennis, 1617).

MD: After the French Revolution, there were, at least as far as I know, practically no more alchemical books with engraved illustrations. That’s a sign that there were no longer the social, cultural, religious, spiritual and philosophical conditions for a meaningful practice of alchemy. The 19th and early 20th century books you mention are not about alchemy but about ‘occult philosophy.’ Once the chance of an agency aimed at changing—at perfecting matter—vanished, there was a cultural shift, a tension to change man. The second half of the 19th century saw the emergence or reemergence of the magus, the individual who, through language, verbal or visual, and through action tries to change, perfect or degrade the life of other individuals. This culture of magic then vanished too, with the human devastations of World War I and the social upheavals that followed. With the exception possibly of the sexual magic of Maria de Naglowska and Aleister Crowley, there starts an epoch, initiated in the late 1920s by the two books of Fulcanelli and still going on, of studies—and, as you say, studies of the studies—of alchemy and magic. There is too much science and too little sacred, today. There is no sacred science. There is no longer a true belief in the power of the stars to influence human destinies. We are out of the territory of magical thinking.

BN: Are you still looking for books for your collection? Is something especially missing?

MD: I am probably still looking. I recently found online, from a bookseller in Toronto, a book I had been in search of for decades. The digital script for my catalog was already at the printer but I was able to include it at the very last minute. At almost 90, I didn’t want to further defy the scythe of Saturn, the god of time and the planet/star under which I was born. I needed to publish the ‘Bibliotheca’ as an indirect autobiography.

BN: There’s no holy grail that has eluded you until now?

MD: Actually, I know of a crudely assembled magical manuscript from the 16th or 17th century that, somewhere in Europe, is still insistently looking for me.

– Bob Nickas has worked as a critic and curator in New York since 1984. He is the author of Theft Is Vision and The Dept. of Corrections.