Books

Alina Szapocznikow’s Radical Instability

By Margot Norton

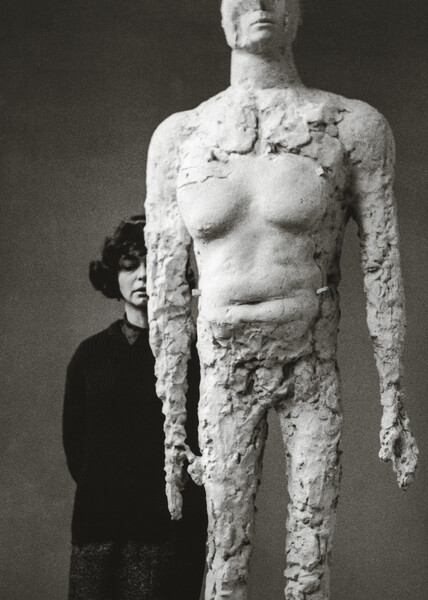

The artist in her studio near Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, ca. 1964. Photo: Władysław Sławny

In March 1972, one year before her untimely death at the age of forty-seven, artist Alina Szapocznikow composed a typewritten text, which is now seen as her artistic manifesto of sorts. The most frequently quoted segment is the one in which the sculptor succinctly articulated, ‘I am convinced that of all the manifestations of the ephemeral the human body is the most vulnerable, the only source of joy, all suffering, and all truth.’[1] And it is reflected throughout her career that her artistic practice would be consumed with the human body, speaking to both the power and the vulnerability of its form. A survivor of the Holocaust and a victim of tuberculosis and breast cancer (the latter would eventually take her life), Szapocznikow rarely spoke of her traumatic experiences in public and rather worked through the scars of her past through her sculptures. Most frequently casting her own body, as well as those of her family and friends, Szapocznikow created inventively constructed and erotically charged corporeal fragments that embody, or perhaps even exorcize suffering, while capturing the volatile and evanescent nature of human life.

‘Nothing is definitive in my work, if not the immediate pleasure of feeling the material, of touching and palpating the distinct material of the mud as children do on a river-bank.’—Alina Szapocznikow

One month after her typewritten note, Szapocznikow handwrote an addendum to the text dated April 1972, which stated, ‘Nothing is definitive in my work, if not the immediate pleasure of feeling the material, of touching and palpating the distinct material of the mud as children do on a river-bank.’[2] This note is significant, for it signals a way of working, of seeking, of searching, of exalting the fleeting moment that would remain of essence in Szapocznikow’s practice. Throughout her career, the artist inexhaustibly experimented with innovative methods and materials, stretching, pushing, and reimagining sculptural possibilities in an effort to capture the ephemeral. Her rigorous practice of re-evaluating artistic vocabularies would contribute significantly to redefining the visual language of sculpture today as artists continue to dismiss the boundaries that separate inside and outside, bodies and objects, self and other.

The artist's studio in Malakoff, France

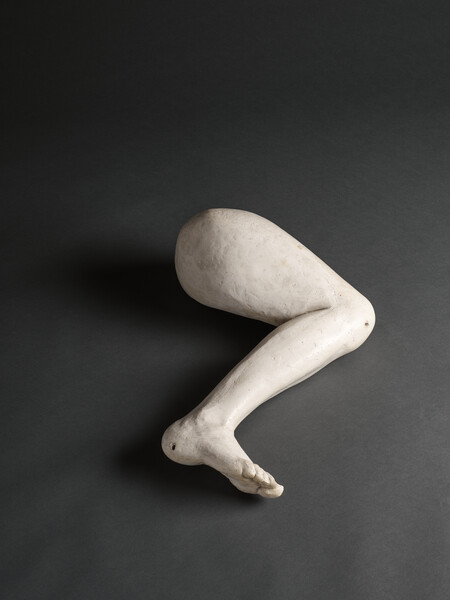

Alina Szapocznikow, Noga (Leg), 1962 © ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy the Estate of Alina Szapocznikow / Piotr Stanislawski / Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris / and Hauser & Wirth

Classically trained in Prague and Paris at the École des beaux-arts, Szapocznikow was well versed in traditional sculptural techniques. In fact, her 1972 text opens with the phrase ‘My work has its roots in sculpture. For years I threw myself into studying problems of balance, volume, space, shadow, and light.’[3] Her early works in stone are attentive observations of the anatomical proportions and volumes of the body, which grew into fragmented and distorted corporeal forms. A pivotal work, ‘Noga’ (Leg, 1962), her first known plaster cast of her own body, was created just prior to the artist’s relocation to Paris after living in Warsaw for twelve years. This work signals a shift in her practice when she would come to cast her body using a variety of experimental materials and focus on representing metamorphosis in sculptural form and the ‘body in pieces.’[4] Szapocznikow reflected back on ‘Noga’ and other casts of her own body in a letter from 1966: Haunted by the increasingly academic nature of abstract art, and at the same time, partly out of my spirit of contradiction and partly perhaps out of some artistic exhibitionism, I made a cast of my own leg and an assemblage of casts of my face . . . Fortunately we believe that in art everything has been already, so nothing has been yet.[5]

Studio on Brzozowa Street, Warsaw, 1965

A view of the artist’s studio from 1965 shows her ‘Noga’ in the foreground resting on a piece of black granite alongside several other plaster-cast sculptures from this period atop wooden pedestals and plinths. ‘Noga’ marks an instinctual turn in Szapocznikow’s practice, transgressing sculptural conventions of the time to dismiss the hierarchy of body structure.[6] Resting gently on its side, the sculpture is no longer a fragment of a whole, but a whole fragment—elevated atop a pedestal as a fetish, an object of desire, at once vulnerable and commanding.

Five years after her plaster cast, she recast the sculpture in bronze, further removing it from the intimate process of casting her own body and giving it increased sculptural stature in its weighty form and glistening finish. From the time in which ‘Noga’ was created, Szapocznikow would enter a period of remarkable experimentation and productivity, casting corporeal fragments in new and unconventional substances such as polyester resin and polyurethane foam (used mainly by the commercial construction industry of the time), and everyday materials such as nylon stockings, newspaper clippings, cigarette butts, and grass.

Alina Szapocznikow, Kaprys—Monstre (Caprice—Monster), 1967 © ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy the Estate of Alina Szapocznikow / Piotr Stanislawski / Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris / and Hauser & Wirth

The artist with Man in Armor (1966). Photo: Marek Holzman

Looking back on her career in her 1972 text, Szapocznikow described herself as ‘a sculptor who has experienced the failure of a thwarted vocation.’ This ‘failure’ or ‘thwarted vocation’ might instead be described as innovation or a deconstruction of traditional techniques. The artist’s embrace of the impermanent and mercurial calls upon sculpture to reflect on these fundamental characteristics of our existence. She famously referred to her work as ‘awkward objects,’ and hoped that they might capture ‘the fleeting moments of life, its paradoxes and absurdity.’[7] In archival photographs, Szapocznikow is often seen posing with her sculptures, placing her casts over her own appendages and playfully echoing her process of merging her body with material. In so doing, she highlights her sculptures as enduring evidence of her process and her body’s indexical relationship to the substances she casts, dismissing the boundaries that separate body (composed of matter) from the material it manipulates.

As recent authors have noted, much has been written about the artist’s biography in readings of her work, disproportionally focusing on her traumatic experiences from concentration camps to recurrent ill health, to the point of overshadowing her crucial contributions to contemporary art.[8] It was not until recently that scholars and curators have positioned Szapocznikow’s practice alongside that of her contemporaries such as Louise Bourgeois, Hannah Wilke, Paul Thek, Tetsumi Kudo, or Lynda Benglis— artists whose experimental approaches transformed the visual language of contemporary sculpture. These artists, while likely not in dialogue with one another, were independently, and almost simultaneously, incorporating unorthodox materials such as wax, latex, polyester resin, and polyurethane foam. Working predominantly in the 1960s and 1970s, their radical approaches to material thwarted the representation of the figure as a fixed, self-contained whole, instead embracing vulnerable substances, fragmented forms, radical instability.

Paul Thek, Untitled from the series Technological Reliquaries, 1966. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York © The Estate of George Paul Thek. Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Genealogy, 1968

In speaking about his Technological Reliquaries or ‘meat pieces’ of the 1960s, American artist Paul Thek echoed these impulses in a 1969 interview: ‘In New York at the time there was an enormous tendency toward the minimal, the non-emotional, and anti-emotional even, that I wanted to say something about emotion, about the ugly side of things. I wanted to return the human fleshy characteristics to the art.’[9] Like Szapocznikow, Thek cast fragments of his own body for his work from this period, which would result in glistening, hyperrealistic representations of raw flesh enshrined in boxes like religious relics or ruins of classical sculpture. His most well-known work, ‘The Tomb’ (1967) included a life-size effigy of the artist cast in wax from Thek’s body, painted pale pink and adorned with a necklace of human hair.

Also in the 1960s, artist Lynn Hershman Leeson, typically associated with her pioneering contributions to media art, created casts of her own body. Her series Breathing Machines of this period would include wax casts of her face in different guises housed in glass vitrines and accompanied by cassette decks, which played the sound of her voice as viewers came near. Also from this period, Hershman Leeson cast eight wax fragments of her lips and chin for her sculpture Genealogy (1968), a work that would signal the artist’s continued preoccupation with the intermingling of death and vitality as well as with the construction of identity and the limits of the self. Hershman Leeson developed many of her works in wax during a period when she was confined to a hospital bed and in an oxygen tent after being diagnosed with cardiomyopathy in 1965. She has described using the material in a state very much preoccupied with her own mortality, noting how the material could register her own ‘imperfections and life scars.’[10]

...Szapocznikow’s works seem to exist in a state of becoming—a crystallized effort to capture life’s constant flux.

Almost simultaneously to Thek and Hershman Leeson, Szapocznikow would come to create myriad casts of corporeal fragments in viscous experimental materials, namely polyester resin and polyurethane foam, which had been used only for industrial purposes up to that time. Like wax, synthetic polyester resin could capture meticulous attention to detail yet retain an ethereal quality unlike traditional sculptural materials such as plaster or bronze. Speaking about this quality in the 2008 book on wax sculpture, ‘Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure’, French philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman described wax as a ‘fixed instability,’ a ‘substance between two states . . . Invested with the value of a haunting memory, a thread, a nightmare, a metamorphosis.’[11]

The Austrian art historian Julius von Schlosser noted a century earlier that the ‘age-old art of ceroplasty [a medical term denoting the manufacture of wax anatomical models] represents ideas of transcendence, ideas linking the perceived world of the senses to a hypostatized supersensory beyond.’[12] Like the wax figures these authors describe, Szapocznikow’s works seem to exist in a state of becoming—a crystallized effort to capture life’s constant flux. Yet unlike wax, which defies mortality in that its form is never solidified and can always be reheated and melted back to formlessness, synthetic polyester resin has a very quick liquid lifespan, and can only be molded for about ten minutes before it starts to gel.

– ‘To Exalt the Ephemeral: Alina Szapocznikow, 1962 – 1972’ is on view at Hauser & Wirth London 7 February – 2 May 2020, and follows on from the exhibition at Hauser & Wirth New York, 69th Street, 29 October – 21 December 2019. The above text is an excerpt from the full essay in ‘To Exalt the Ephemeral: Alina Szapocznikow, 1962–1972’ by Margot Norton, who is Curator at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York. With Jamillah James, she is curating the 2021 edition of the New Museum Triennial. Before she joined he museum in 2011 as Assistant Curator, Norton worked as Curatorial Assistant at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

[1]Alina Szapocznikow, ‘Mon oeuvre puise ses racines…,’ typescript, signed and dated March 1972, in the Alina Szapocznikow Archive/Piotr Stanisławski/National Museum in Kraków.[2]Szapocznikow,‘Mon oeuvre puise ses racines…’[3]Szapocznikow,‘Mon oeuvre puise ses racines…’[4] Art historian Linda Nochlin traces the developments of the partial image, fragmen-tation, and loss of totality in artistic representation from Neo- classicism to modern art in her influential text The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1994).[5] Alina Szapocznikow, letter to Jerzy Stajuda, later published as “Z Paryża pisze Alina Szapocznikow [o Giacomettim],” Współczesność 5 (1966), quoted in Alina Szapocz-nikow (Warsaw: Institute for Promotion of Art Foundation, Galeria Zachęta, 1998), p.128.[6] For further analysis of this sculpture see Agata Jakubowska, ‘Alina Szapocznikow’s Leg and Goldfinger: Between Reality and Illusion,’ in Alina Szapocznikow: Awkward Objects, ed. Agata Jakubowska (Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art, 2011), pp.123 – 31.[7] Szapocznikow, statement, March 1972.[8] See Elena Filipovic and Joanna Mytkowska, Introduction, Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972 (New York: Museum of Modern Art and Brussels: Mercatorfonds, 2011), 10–15.[9] Paul Thek in an interview with Emmy Huf, ‘Paul Theks Kippenhoek in het Stedelijk: Interview,’ De Volkskrant (Amsterdam), April 26, 1969.[10] Lynn Hershman Leeson in an interview with Moira Roth and Diane Tani, 1991, in Lynn Hershman Leeson Papers, M1452, Box 19, Early Writings: Folder 2, Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.[11] Georges Didi-Huberman, ‘Viscosities and Survival: Art History Put to the Test by the Material,’ in Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure, ed. Roberta Panzanelli (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2008), 154.[12] Julius von Schlosser, ‘History of Portraiture in Wax’ (1911), in Ephemeral Bodies, 175.