Conversations

A conversation between Anna Maria Maiolino and Barbara Corti

Anna Maria Maiolino working on her 1974 solo exhibition at Galeria Arte Global, São Paulo

Barbara Corti is a Senior Director in New York and has been involved with the gallery since its early days in Switzerland. Barbara oversees Hauser & Wirth’s 22nd Street space and works closely with specific artists, including Anna Maria Maiolino.

Barbara Corti: You left Italy for South America with your family as a teenager in 1954. Now, over six decades later, you are having your largest exhibition ever at PAC Milano. Does this feel like a homecoming of sorts? How do you think your early years in Italy impacted you personally?

Anna Maria Maiolino: I left Italy in 1954 when I was 12 years old, as an immigrant. It was not my choice. Due to the postwar economic downturn, my family went to Venezuela, and then to Brazil, in search of better means of making a living. This exhibition at the PAC in Milan has reconciled me with my childhood in Italy, the country in which, when I was a child, I blamed for all the hardships I went through with my family in that period of our immigration. Italy failed to look after me, my infant soul told me, putting all the blame of abandonment on her.

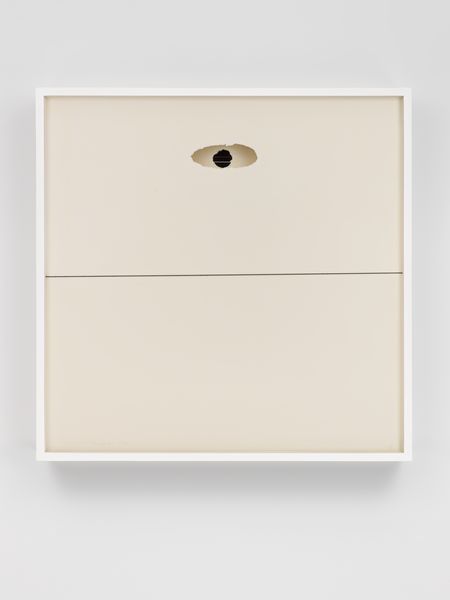

Anna Maria Maiolino, Untitled, from the Desenhos Objetos (Drawing Objects) series, 1974/2010 © Anna Maria Maiolino

Anna Maria Maiolino, Untitled, from the Desenhos Objetos (Drawing Objects) series, 1974/2010 © Anna Maria Maiolino

BC: How did you come to the exhibition title ‘O Amor Se Faz Revolucionário (Making Love Revolutionary)’?

AMM: ‘Making Love Revolutionary’ is the final sentence of an installation project, which I wrote in 1991, but never carried out, and so it is a previously unseen work. It is a political-poetic creation about the role of the Plaza Mayo mothers in Buenos Aires, Argentina, during the military dictatorship. These brave and courageous women, driven by love for their near and dear ones who were tortured and killed, disappeared; through their cries of love they were able to bolster the resistance and stop the military repression of that historic time. Diego Sileo, curator of this show, also thought that the title was suitable seeing as in my works from the 60s and 70s, just like my more recent work, the performances are works that present discourses of resistance against ideologies and dominant social impositions through metaphors and metonyms. Love becomes revolutionary whenever wetake a stance in favor of human rights and against acts of violence. On the other hand, the curator thinks that my work, developed in different media and in multiple discourses, demonstrates an inquisitive spirit with an anti-conformist passion in the face of conventional aesthetics, and hence we could dare name this great retrospective exhibition: ‘O Amor Se Faz Revolucionário.’

‘Love becomes revolutionary whenever we take a stance in favor of human rights and against acts of violence.’

BC: Can you speak about the role that performance plays in your current practice? It seems like it has become less central to your work since the 70s and 80s, yet it is still very much a part of you? You will premier a new performance piece at PAC. What was your conceptual approach to this new piece? How does it differ from your earlier work?

AMM: Today the videos, the sound works, and the performances—as the Super-8s and installations were in the past—are answers in view to the schizophrenia of the dogmas and modes of our times that imprison us in suffocating schemes. With the performances, I seek to give ethical answers so I can give shape to my craving, inherent to the subversion of repressions. I mean, to notice and resist repression in an attempt to make an anti-conformist, politically interventionist—and therefore revolutionary—art that tries to retrieve what the human being has of essence, dignity, and that can also lay the responsibility on the ethical conscience in the face of the generalized violence and misery of today’s world. Being guided in this same direction I developed ‘Al Di Lá Di’, the performance that will be presented at PAC in April.

Anna Maria Maiolino, Mais de Cem, 1993 © Anna Maria Maiolino

BC: In your Desenhos Objetos (Drawing Objects) series, which you started in the 1970s, you treat paper as a sculptural element instead of just a flat surface; you essentially made drawings with paper instead of drawings on paper. Where did this idea originate? How is working with paper as a sculptural medium different than working with clay or concrete?

AMM: I think that the artwork is initially developed through the artist’s sensibility and evolves with mental participation, the concept. I believe that changing plans and changing materials allows the artistic discourse of the works to be extended. In this regard, the Object Drawings of the 1970s emerged and then the series of molded sculptures.

BC: You have explored almost every medium: printmaking, photography, performance, drawing, painting, video, and sculpture. How do you view these various art forms in your practice? Do you consider your art as based on material or rather ideas?

AMM: My restlessness and my great curiosity led me to experiment with different media and materials. On the other hand, the changing use of media is a search for the most efficient means to give shape to a specific question in my mind.

BC: Part of the show at PAC will travel to Whitechapel in London in the fall. Do you develop your shows in reaction to the given architecture?

AMM: I try to adapt my shows in respect to the space that the institutions offer me.

Works by Anna Maria Maiolino are featured in Hauser & Wirth’s presentation at Art Basel, from 13 – 16 June 2019.