Conversations

A conversation between Larry Bell and Graham Steele

Installation view, ‘Larry Bell. Hydrolux’, Art Basel Unlimited, Basel, Switzerland, 2019 © Larry Bell

- 10 January 2019

Graham Steele is a Senior Director based in Los Angeles. He has been instrumental in developing the gallery’s presence in the city, and also works closely with Larry Bell in the continuation of a decades-long relationship.

Bell’s Hydrolux, a multi-media installation embodied via closed circuit cameras, projectors, strobe lights, and water, was recently on view as part of the artist’s comprehensive survey at ICA Miami, and will be presented at Unlimited.

Graham Steele: Tell me about the environment in which you made this painting. It’s 1959, where are you? Who’s teaching you? What are you doing?

Larry Bell: Well, it was done in my little studio, which was the basement of the apartment I lived in when I was going to art school. And it was—it came out as the composition that you see, based on a bunch of drawings of little squares that I did in one of my classes. And essentially I had, I don’t know, a couple of hundred little pieces of white paper and this tagging bond that I made these squares on. And the challenge was to just keep repeating the squares by making lines that made up squares on individual pieces of paper. And then I went into the studio and started working on the painting, then that’s what came out.

GS: So this came out of an exploration about specific geometry. And in the square we’re sort of looking back—thinking, of course, about your iconic cubes and the kind of painting that it led into. Would you say that this was an important turning point for you? It’s interesting that you kept this painting so beautifully for 70 years.

LB: Well, that’s because I’ve kept it all this time. I haven’t seen it in quite a few years actually. I have a portfolio somewhere here that contains all of those little black and white drawings that were generated just prior to my doing that canvas.

GS: I think the art historians of the future are happy that you didn’t throw these away. Going back to the orange painting—was this when you were working with Bob Irwin as your teacher at the time?

LB: Yes.

GS: In a way, this was a transitional moment and your first mature painting. What was his response to it?

LB: He never saw it.

GS: He didn’t? Did you show it to anyone?

LB: No. I did it and maybe my roommate—a guy named Dean Cushman—might have seen it. I never showed it to anybody else. I never even showed it at an exhibition. I just brought it with me, along with a few other things, as I moved from one studio to another.

GS: So it’s like your first secret piece! One of the interesting things that I was thinking about, Larry, in terms of a motif, is that it reminds me of Bette and the Giant Jewfish; if you think of your interest in pattern, it comes out in a very different way. Even in the late series, with the cube within a cube, you come back to patterns at the end of the cube series and then right before you launch into it.

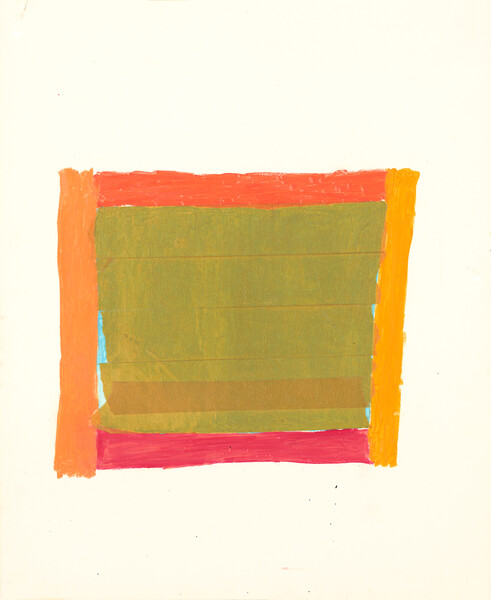

Larry Bell, Untitled, 1959 © Larry Bell. Photo: Jeff McLane

Larry Bell, New York NY, 1966 © Larry Bell

LB: I wish I could give you an articulate response to that. But the piece in this basement studio I had—I didn’t know where I was going and I didn’t know where I was coming from either. So that’s the perfect place to be. What came out was just the intuitive response to an inner challenge and that’s the image of it.

GS: Totally! I think what’s interesting though, Larry, is that you know in that intuitive moment you tap into something that you continue to tap into for 70 years. I think that’s why it’s so exciting to see this piece, and in a way, why it’s surprising that the piece has really never been shown before. So it’s an exciting thing to see that.

LB: I hope I’m not all embarrassed by it all. I just looked at the images that were photographed of the drawings in that folder from school and some of those are really interesting—the diagrams of the squares. And then there’s also a series of sketches that must have been something I was thinking about for the patterns on the cubes with the original elliptical cubes—there are sketches for those things, they are kind of very technical drawings.

GS: Let’s talk about Hydrolux because everyone was excited about seeing this piece in Miami, and this is where the curators from Unlimited saw the piece and immediately became very excited. Can you tell me about the context in which you made this piece? One of the things that I find really interesting about that work was that it became the most photographed work in your show in Miami, and there was something about the idea of surveillance and of you being implicated in the work that was very prescient. Talk to me about what was happening in 1980 and where this piece came from.

Drawings for Hydrolux © Larry Bell

Drawings for Hydrolux © Larry Bell

LB: Well I was very intrigued by something I saw when I was doing an installation of a piece called the Iceberg at M.I.T. I met a fellow named Harold Edgerton, who was a professor there, who invented the strobe light. In his studio at the school, where I was treated to a visit, he came in and turned on the light and then he turned on a faucet. The water, instead of coming out of the hydrant and going into the drain, came out of the drain and was going into the faucet. It was absolutely stunning and baffling to see such a thing. So I finally figured out how he did it. And then I went to try and make some kind of a display, a sculptural display, which included that improbable activity and I was going to call that The Improbable Flow. I worked on several kinds of possible commissions—one was for the IBM Building on 56th and Madison, because I was selected to put in an idea for that.

And we made a maquette of a sculpture piece that was supposed to sit out just south of the entrance of the building and water appeared to be running backwards on the threading board. It was a big triangular wedge, 18 feet tall. The water would cascade down from the top to the bottom, but it would appear that the water was going from the bottom up to the top. So we made that model, and I was really impressed with how well it performed and decided to carry on playing around with light and water. There was very little money to experiment with these kinds of things, other than just in a small way with garden hoses and sprinkler nozzles and stuff like that. And we built a strobe light where we could pulse the water and make it do strange things. In the studio, we built a lot of components that could be used and improvised to disperse the water. In other words, a manifold that would drop the water and a tank that would catch the water. And then lights and things like that and video projections into the water that were interesting…

‘And a lot of the stuff that happened was improbable. I didn’t plan it. It just happened. And that’s the story of my life—just letting things happen and enjoying the possibility that anything can happen, anytime.’

Larry Bell, ART-SCHOOL - 6, ca. 1958 © Larry Bell

Installation view, ‘Larry Bell. Hydrolux’, ICA, 2018 © Larry Bell. Photo: Fredrik Nilson

GS: Why video, Larry? Because so much of what surprised people was this really prescient use of video and this idea of surveillance. The fact that there is a sense of discovery as you realize the shimmering video on one side is actually your projection behind you, doubled and tripled.

LB: Well it’s quite simple. I wanted everything about the piece to be improbable. In Miami where the viewer was seeing three different times—looking at the piece in the shadow of the viewer was projected back onto the water. I love the improbability of the whole thing. And a fantastic thing happened in that room at the ICA—the air became ionized because of the falling water. And so it felt really great to be in the presence of that. The water and the ionization of the water charmed the viewers. And then the visuals of the piece added to the charm of it. And a lot of the stuff that happened was improbable. I didn’t plan it. It just happened. And that’s the story of my life —just letting things happen and enjoying the possibility that anything can happen, anytime.

GS: What came first, was it Hydrolux or was it The Improbable Flow? Because obviously there are relationships between them.

LB: The Improbable Flow actually came first, however the whole series was called Hydrolux: Light and Water. So The Improbable Flow was part of Hydrolux, the concept. It was an aspect of Hydrolux where the water went backwards.

GS: Does the piece you are showing in Basel have the strobe light?

LB: I don’t know. What we ended up with was a surprise. I love the way it all looked. Plus, I could feel that ionization in the air. I wasn’t expecting that. I really never had such a successful shower stream. What came out was something completely different, but still a pure form of Hydrolux.

GS: It’s exciting for people to know that the Hydrolux series opens up.

Works by Larry Bell are featured in Hauser & Wirth’s presentation at Art Basel Unlimited, from 13 – 16 June 2019.