Conversations

Lorna Simpson in conversation with Thelma Golden

Thelma Golden and Lorna Simpson in front of ‘Blue Dark’ (2018), Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street, 2019 © Lorna Simpson

For more than 30 years, Lorna Simpson’s powerful work has explored the nature of representation, identity, gender, race, and history. On the occasion of the artist’s first exhibition at Hauser & Wirth in New York, Simpson was joined by Thelma Golden, Director and Chief Curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem, for a conversation about her work at this significant moment in her career. Starting with Simpson’s suite of new large-scale ink paintings, the discussion covers the artist’s childhood realization as a ballet dancer and the cultural importance of the color blue. This year, Simpson was awarded the J. Paul Getty Medal, honoring her extraordinary contribution to the arts.

Thelma Golden: So, this exhibition really sits within a trajectory of your work that began in 2015. It seems appropriate and even necessary, to mark the beginning of that passage of your work when you began painting. And when that work first came into the world, it was in our dear, now departed, friend Okwui Enwezor’s Venice Biennale. I remember at the time that Okwui was doing studio visits, and talking to you and many other artists that we know and love. We were having our curator conversations we always had, and he said to me, ‘Oh I saw Lorna today.’ He was deep in the planning for his Biennale that was called ‘All the World’s Futures’, and said, ‘Lorna is painting.’ I said, ‘Lorna is painting?’ And he replied, in that Okwui way, ‘Lorna is painting.’ What I know is that you hadn’t quite started yet, right? You were in it, you were doing it, but that moment sort of was the beginning. So, can you just go back for a moment and tell us how after years of committed conceptual practice—from photography to video, to a use of found object in both two-dimensional form and others, and even to the moment of drawing— how, where, and when did the seed of this practice that we are now seeing really begin?

Installation view, ‘Lorna Simpson. Darkening,’ Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street, 2019 © Lorna Simpson. Photo: Thomas Barratt

Lorna Simpson: I think as an artist I’m constantly challenging myself. I’ve come to realize that it’s not always about feeling comfortable, safe, or understanding what you’re doing and that risk is involved with that. You put at risk having a good show, you put at risk that the work might not turn out well. In some ways, I had been thinking about my current practice since working with drawings and collages, and how I could do this on a different scale. Over the years of being in this circle of artist friends who are painters, it kind of horrified me. They'd be like, ‘So Glenn [Ligon], where do you get your canvases from?’ or ‘What do you think of this painter?’ It seemed like I was jumping into an arena not out of nowhere, but certainly into a space occupied by friends who had been painting for as long as I'd been doing my practice. I was just a little bit afraid. At the time, I wouldn't call what I did painting. I would say, ‘They are like drawings. Not paintings. They're big drawings in a way.’

The experience of making the work—what it takes to make it and the way that it comes to me— is more important than anything else.

I think there was a moment I decided, ‘You have to leap.’ I don't have this secret practice of, ‘Here's the paintings that I never showed, or here's the photographs I never did anything with for 20 years.’ I do it, and for some reason everything that I do gets immediately presented. That’s always been the case. There's a bit of fearlessness about it. With Okwui, we were very close. Our daughters grew up together, but there is also this professional relationship. Although we were very close, I'd made no assumption that I was going to be in the show at all. I proposed a couple of examples. He was intrigued and of course hugely busy, and said, ‘Okay, let's try this.‘ Then I got bold and I was like, ‘Not four paintings, five paintings.’

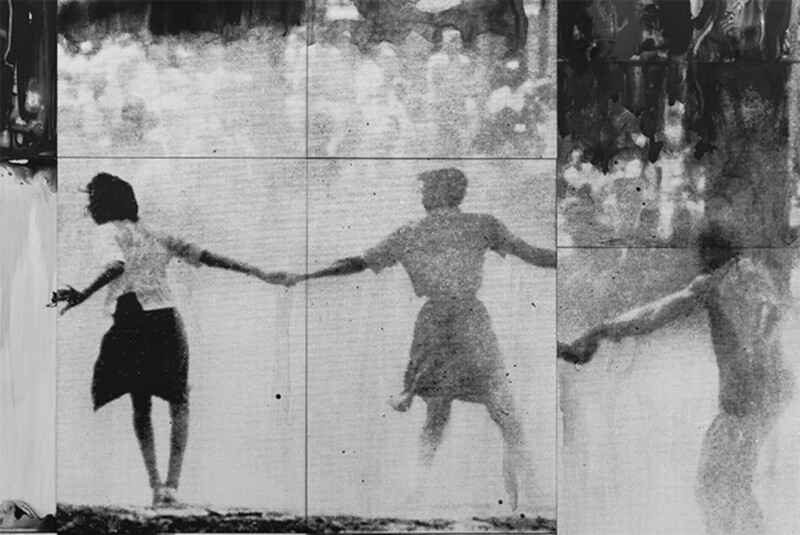

Lorna Simpson, Three Figures (detail), 2014 © Lorna Simpson. Photo: James Wang

It was an amazing opportunity combined with the pressure of, ‘Okay, I’m going to do this. They’re just going to leave the studio and they’re going straight to Venice.’ I’d never done that before. It was an amazing experience and I am so happy that he was pleased with the results, but I am used to working in public in a way. I don’t have an interior attachment to failure or judgment. The experience of making the work—what it takes to make it and the way that it comes to me— is more important than anything else.

TG: You’ve always been super courageous in the way in which you have charted the course through, not just your practice, but also your approach to subject. To fast-forward to this moment, now that you fully are thinking aesthetically in this form, can you talk a bit about the actual beginning of the ideas that formed this body of work?

LS: The beginning of this idea started with a presentation at Frieze New York three years ago. And in that presentation, I had an obsession with imagery of ice, icebergs and mountain tops. All of the images here are constructed images, using different elements that are combined together.

TG: From where?

LS: From National Archives and from Associated Press photographs. A lot of the images are from the turn of the century—volcanic explosions mixed with pictures of oceans. They are imagined environments that suggest a real place; the nighttime version of my works from a few years ago, clothed in this darkness.

TG: This exhibition is titled ‘Darkening.’

LS: Yes, for me the darkness is about the nighttime as is present in many of the works, but I also feel that living in America right now is like living in a darkening, a very dark period. So there was this way of thinking about color and thinking about night, but also about atmosphere and inhospitable conditions, and how to survive those conditions.

Lorna Simpson, Blue Dark, 2018 © Lorna Simpson. Photo: James Wang

Lorna Simpson, Source Notes, 2019 © Lorna Simpson. Photo: James Wang

TG: Would it be fair to say that the relationship of these works to abstraction has a relationship to the way in which your former work used language as a way to think about multiple meanings? What we understand and what we see is somewhat ambiguous.

LS: And fragmented. I think because the early work was poetic and deconstructed narrative, I wanted to suggest or point to narrative, selecting these vertical fragments of text from Ebony magazine editorials, as opposed to giving them full form. Whether it’s abstraction or figuration, I think there’s always a desire for narrative from the viewer.

TG: In this show there is a series of Special Characters. Can you talk about those works?

LS: They are faces from ads—fashion or wig ads from Ebony magazine—that superimpose two or three different faces upon one another. The weird thing working on this series was that depending on the position of the face, regardless of what faces we chose, they all conform… they kind of all look similar. They are surreal portraits in a way. For me, the photo collages are this amazing surreal, very simple, exploration of my subconscious over the course of time.

Lorna Simpson, Special Character #5, 2019 © Lorna Simpson. Photo: James Wang

Lorna Simpson, Special Character #1, 2019 © Lorna Simpson. Photo: James Wang

TG: They also introduce color in a new and interesting way. Did they change the way you were thinking again about this process of painting by really thinking about color as an important element of the work?

LS: Yeah, I realize my work is very monochromatic.

TG: I mean you've worked in black and white for what, 15 years?

LS: A long time. Color can be a color, but it’s still monochromatic to me. In terms of imagining the exhibition, there are specific hues that go through the show, but the portraits seem separate in a way, since they didn’t need to be imbued in the same sense as the landscapes.

I feel that living in America right now is like living in a darkening, a very dark period.

TG: If there is a line through your work, it is the figure, and very specifically the black female figure. Much of the ground that your work has broken has been about the way in which that figure is understood. That sort of lives as an important part of your artist legacy, really shifting the space in which the black female figure has been understood. And here she is again. Who is she now in the work and in the world?

LS: In terms of thinking about the show and working on the landscapes, it was necessary to connect this with the figure in my work. In all these different explorations since Venice, it’s important to return to that original exploration and to see what I would come up with, but differently, because these configurations are collaged images drawn from multiple sources.

TG: And using, of course, the important and almost essential source of material for you, which exists in Ebony and Jet.

LS: That is the source material for the entire exhibition, and, in a way, also my work over the past five years. I have so many Ebony magazines in my studio, which are important as a reflection of the studio, but also show how totemic Ebony is in terms of my development and thinking about it as a lens of American history.

Installation view, ‘Lorna Simpson. Darkening,’ Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street, 2019 © Lorna Simpson. Photo: Thomas Barratt

TG: Do you think in some ways that this is an indication of the way in which you began to read photographs and photographic imagery? And this is why photography is such a core in your work and forms such a base of inspiration?

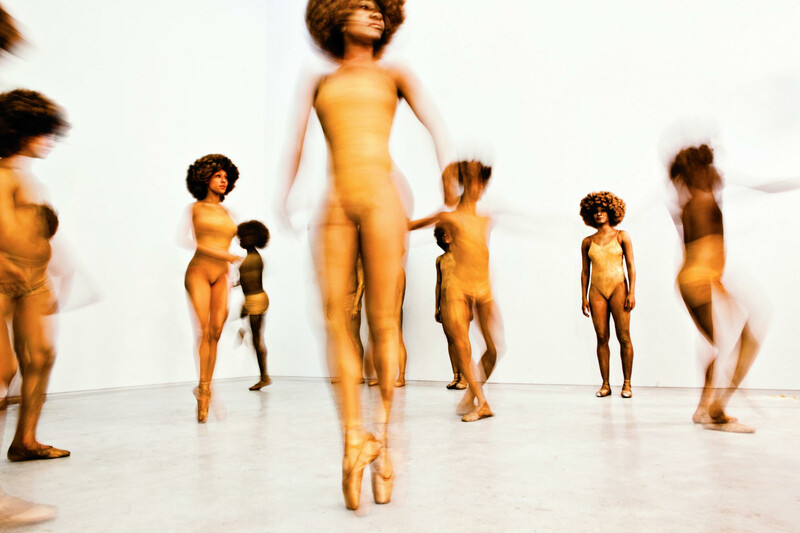

LS: I think my reasons for being an artist are twofold. It’s to have a voice, and secondarily as a way of thinking about my own experiences. As a child I studied ballet, which was a great experience. The comradery and development of one’s body, learning how to dance, and then performing at the Lincoln Center. Once on stage, I remember being quite disappointed because I wanted to be in the audience. I could see the choreographers and the instructors had really brought an idea to fruition, with gold Afros and body paint, and I really wanted to see their vision play out. In that moment I realized, ‘Okay I’m not a dancer. I don’t need to have this connection with an audience. That’s not who I am.’ I was the person who wanted to see something like that come to fruition. And because my parents were taking photographs that did not come out, I had no photographs of the experience. Maybe that led me to photography.

Lorna Simpson’s film ‘Momentum’ (2011) features a group of New York dancers selected to reenact her own stage debut performed at the age of eleven © Lorna Simpson

TG: Our friend, the artist Glenn Ligon curated a monumental exhibition called ‘Blue Black’ where he looked at the implications of those colors and quite literally traced an incredibly deep and profound line about the idea of the blues and the idea of blackness. The idea of a kind of color theory matched against cultural resonance. Can you just talk about the color blue or the blues?

LS: That was what was so important about inviting Robin Coste Lewis to give me access to her amazing accomplishments as a writer and poet. At the beginning of the exhibition we have an excerpt from her latest project about the Arctic. This poem is about memory and time—kind of like Homer’s Odyssey—linked to living in Los Angeles, living in Crenshaw, and her life. It’s about place, but it’s contemplating a state of mind as well. Conceptually, Robin and I have these almost parallel tracks. It’s really interesting to connect with another artist and to find both your intentions and fascinations are aligned. That to me is really inspiring. For what I can’t bring words to or what I am sensing about the work and thinking about. Glenn’s exhibition at the Pulitzer was really amazing. And it was at the time where I think I had made the first presentations featuring these blue mountains works. Blue is through all cultures, and possesses a poignant and amazing gravitational pull. I mean, we live on this blue marble in the middle of the universe, so blue is that very important color. Of course, culturally it’s the blues, ‘blue black’, and in terms of English colloquial use of the word blue— particularly ‘blue black’ culture— that’s absolutely important.

TG: I think it would be nice to end on the poetics and to ask you if you would read the last few lines of Robin's beautiful poem which opens up the poetic space this work lives in. LS: Okay. By Robin Coste Lewis, just the last five lines. I am blue. I am a frozen blue ocean. I am a wave struck cold in midair. The wave is nude beneath her blue dress. Her skin is blue.

‘Lorna Simpson. Darkening’ is on view at Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street, from 25 April – 26 July 2019.

Lorna Simpson was born in Brooklyn, where she continues to live and work. Simpson came to prominence in the 1980s through her pioneering approach to conceptual photography, which featured striking juxtapositions of text and staged images and raised questions about the nature of representation, identity, gender, race and history.

Thelma Golden is Director and Chief Curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem, the world’s leading institution devoted to visual art by artists of African descent. Her curatorial experience includes a decade at the Whitney Museum of American Art, during which time she organised numerous groundbreaking exhibitions, including 'Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in American Art, in 1994'.

Robin Coste Lewis is the Los Angeles poet laureate and a winner of the National Book Award for her 2015 book of poems, ‘The Voyage of the Sable Venus.’ Born and raised in Compton, California, Coste Lewis earned an MFA from New York University’s Creative Writing Program, where she was a Goldwater Fellow in poetry, and a master of theological studies from Harvard Divinity School.