Essays

Remembering Sister Wendy Beckett (1930–2018)

by Linda Yablonsky

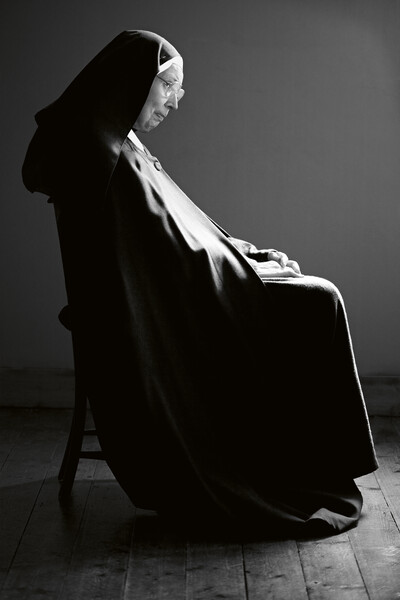

Self Assignment, 2009. Photo: Ethan Hill. Courtesy Contour RA Getty Images

- 22 March 2019

As an evangelist for art, Sister Wendy Beckett knew how to find God in the details. Being a Roman Catholic nun had something to do with it, but salvation was not her brief. Rapture was.

During one of her televised tours of the world’s great museums, she spoke of Michelangelo’s Pietà in the rhapsodic terms of a steamy romance novel. Enunciating each word like a poet serving a sumptuous meal of the plainest English, she said, ‘I’m struck by the loneliness of these figures, grieving and beautiful,’ viewing Mary ‘like a mountain and Jesus like a great river flowing down her.’ The image is wonderful, even charmed. But what made Sister Wendy so captivating a personality, even for those of us in the contemporary art world who followed her televised exploits in the ’90s, was her wily ability to play against type while remaining very much in the character of a senior holy sister being ravished by art before our eyes. The incongruity was more than visual. With the Pietà looming over her shoulder, Sister Wendy looked directly into the camera and gave it her chipmunk’s smile. ‘They’re both isolated,’ she said of her faith’s bedrock ‘and yet so intimately united—because they belonged to one another.

‘Michelangelo himself was a very lonely man,’ she continued, as if speaking of a dear friend, ‘a man of enormous, tempestuous passions who lost his mother when he was very young.…He was always seeking what he shows us here, this beautiful young mother, too beautiful ever to grow old.’ Here, Sister Wendy paused, as if embarrassed to admit, ‘I don’t myself feel the anguish of a mother for her child; I feel more the wonderful companionship of male and female.’ Which other cloistered nun would have held up Jesus and Mary as exemplars of eroticism? For that matter, which television personality? The art historian Leo Steinberg was the first to call attention to the overt sexual imagery of religious subjects in Renaissance art, and Sister Wendy, educated at Oxford, no doubt read him. But Steinberg didn’t live under vows and wasn’t followed by millions of adoring fans.

Which other cloistered nun would have held up Jesus and Mary as exemplars of eroticism? For that matter, which television personality?

A nun since the age of 16, Sister Wendy spent 15 years teaching in her native South Africa. After suffering three epileptic seizures, she repaired to the life of solitude she never relinquished, even after her discovery by a producer for the BBC, who had read her 1988 book, the first of 25, Contemporary Women Artists. (Ahead of her time, I’d say.) She made her television debut in 1991, during the gender-and-identity-politics-afflicted Culture Wars, and leapt instantly to international stardom despite her age (67), buck teeth, oversize spectacles, bad posture, slight lisp and total lack of vanity. Glamorous she wasn’t. And yet, when descending a museum staircase or gliding through its galleries, her robes took on the property of a superhero’s cape, empowering her to sweep us along in her wake.

Offscreen, she secluded herself in a windowless trailer outside the tiny rural village of Quidenham, England, on the grounds of the Carmelite monastery to which she donated all her earnings— reading, praying and thinking. Despite her cloister, she appeared entirely conscious of the premium her medium placed on entertainment value. And though she never went to the movies, she also seemed fully aware of pop culture’s infatuation with women who betroth themselves to God. Think of the Singing Nun or Sally Field as The Flying Nun or Audrey Hepburn somehow stylishly cloaked in her novitiate’s habit throughout The Nun’s Story (1959). There was the unimpeachable Deborah Kerr as a conflicted nun in Black Narcissus (1947) and, on the other end of the spectrum, the hard-nosed Mother Abbess in The Sound of Music—all worshipped by the masses.

The figure of the stern sister was familiar even to someone like me, who grew up in a Jewish household. As a young girl, I was fascinated by the stories that neighboring Catholic-school kids told me of their wimpled teachers—punitive women who rapped their knuckles with a ruler, put them on detention for wearing red shoes, and forbade sex education of any sort. As a young adult, I started to believe that women who made it through Catholic schools were formidably promiscuous. One such temptress I knew became a prominent dominatrix. ‘I’m so bad!’ she would bray at a full moon. ‘Spank me! Save me!’ Sister Wendy could be just as sensational. Remember when she said, in reference to a Stanley Spencer painting, ‘I love all those glistening strands of hair, and her pubic hair is so soft and fluffy’?

Sister Wendy Beckett at the National Gallery in London, 1997. Photo: Geoff Wilkinson. Courtesy Geoff Wilkinson and Shutterstock

Professional critics resented her popularity, pooh-poohing her reverential commentaries as sentimental claptrap. For me, a critic who dreamt from an early age of having her own TV show, she was a role model. Was she any less authoritative than the red-faced Time magazine critic Robert Hughes, who never hid his contempt for contemporary art? Listen to Sister Wendy on the same ‘Whenever I want to indulge in melodramatic hand-wringing—about four-fifths of contemporary art—I think of an artist like Balthus, who’s major.’ Some of us might have wanted to offer more options, but not before giving her credit for the surreal narrative she imparted to a painting by that agreeably unsettling artist. In an interview with Bill Moyers, Sister Wendy even defended Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ.

She celebrated artists who pushed boundaries and ‘magazine-y’ critics who dismissed out of hand Serrano’s amber-red photograph of a drowned ‘It’s hard to judge a work in our own time,’ she told Moyers, sensible and forgiving as ever. ‘Comfortable art is easy,’ she added. ‘You don’t have to think about it. Real art makes demands.’ Sister Wendy could be cloying but also acerbic and aphoristic when the occasion suited. Jan van Eyck gave the suffering bride in the Arnolfini wedding portrait ‘horrid green dress.’ Mark Rothko ‘made religious paintings without religion.’ Picasso was the master of invention who ‘triumphed in the ferocious power of the ugly.’ For a woman who spent much of her life in silence, she was an effective and prodigious communicator. ‘The great gift of the 20th century to artists,’ she told us, ‘was this growing sense that they weren’t bound by the’ —an insight that, by itself, should earn her admittance to the pantheon of modern critics.

Yet I never thought of Sister Wendy as a critic. For me, she was the greatest museum docent the world has known— exactly what everyone wishes for in a guide through art history: well-informed, articulate, open to challenge, impassioned, never patronizing. She was less like the self-important Hughes than the chatty and disarming Anthony Bourdain, who took us on his journeys through the world of food without a hint of snobbery. In the final episode of her ten-part PBS series, Sister Wendy’s Story of Painting, she introduced Pop Art from a booth in a New York diner. The hokey setting was probably her director’s choice, but she made it work. Considering a silkscreen painting of multiple Marilyns by Andy Warhol, she said, ‘Glamour. Sex. Death. I so wish he’d known Princess Di.’ A moment later, she asked, ‘Don’t we all have a struggle with the mystery of death?’ Sister Wendy died last year, a day after Christmas, at 88. I hope she was at peace with both the secular and the monastic worlds, which she had bridged so well with her infinite, and infectious, sense of the marvelous. ‘You’re a powerful artist if you create from your own truth,’ she once said. The sentiment may have sounded like a cliché, but she lived it to the fullest.