Essays

In the Artist’s Words: David Smith Origins and Innovations

by Peter Stevens

David Smith in his ‘summer shop,’ Bolton Landing, New York, 1936–37 © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth

‘The words I use in talking about art do not bear close relationship to making art, nor are they necessary directives or useful explanation. . . . When I work the train of thought has no words, it is simply all in the visual world, the language is image.’—David Smith, ‘The Language Is Image,’ 1952

David Smith claimed a great distrust of words. He saw written language as a means of limiting understanding, and of delineating the boundaries of experience. His life was devoted to challenging boundaries by communicating, through the images his works created, a language that he believed held deeper and more valuable truths. His complex and contradictory nature, however, also led him to produce a rich record of his thoughts in written form.

In the exhibition 'David Smith Origins and Innovations', Smith’s voracious appetite for open-ended exploration of methods and materials, and of form and image, is represented by an inclusive selection of sixty-six works. We see, for example, in a rare and little known early photograph, Untitled (Ship montage), ca. 1930, a constellation of elements in a collage of line and plane, industrial form, pure geometry, and fragments of actual objects—a ship’s wheel, a mast, and a sliver of the sea—the structure and complexity of which are surprisingly echoed two and a half decades later in a well-known, large-scale welded steel sculpture, ‘The Five Spring’ (1955–56). Similarly, visitors will experience the intricate networks that existed for Smith across the boundary of time or limitations of media as he explored the potential for drawing and its relationship to space. The free accumulation of gestures, brushed with the artist’s invented ‘egg ink,’ in ∆∑ (1957), resonates with the iconic, open construction of found parts of abandoned farm machinery in ‘Agricola VIII’ (1952), as well as with ‘Untitled’ (1932–33), an ink drawing from a series of works inspired by Smith’s trip to the Virgin Islands.

The artist’s seemingly inexhaustible inventive approach to the figure ranges through the show, in pieces including the glistening stainless steel ‘Three Circles Related’ (1958–59); the somehow lushly austere, painted steel ‘Tanktotem IX’ (1960); and the carefully crafted, unique cast bronze, surreal figure, ‘Aftermath Figure’ (1945)—all of which seem to have leapt from paintings from the 1930s. There are collages of bits of bone, expressively painted in enamel, and a small black clay animal form abstractly squished by the artist’s fingers. Highlighting Smith’s poetic balance between figure and abstraction, and his fusion of images from industry and nature, the exhibition presents a kind of cosmology rather than an argument or narrative. By enabling visitors to freely experience the links, the echoes of form, or poetic reference from piece to piece, our hope is that the exhibition allows what Smith wanted most: for his work to be experienced without prejudice and to connect to visions that are shared by us all.

David Smith with his sculptures at his studio in Terminal Iron Works Brooklyn, New York ca. 1937 © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth

It is equally important to allow Smith’s own words to communicate the complexity of his beliefs and the ambitions that underlie them. Despite his distrust of language, or possibly because of it, Smith wrote extensively throughout his life. He carefully crafted speeches and texts with assertive clarity and poetic power, not as a means of explaining his work, but as a passionate argument for active open engagement with it.

‘Before letters—consequently words—existed, the artist-sculptor made symbols of objects. The objects depicted were identity memories that came purely from the artist’s mind. The pragmatists later made words and, to this day, turn these symbols against the artist by demanding the ‘what does it mean’ explanation when the formation all along was of artist origin and represented a statement requiring only visual response and association.’ —David Smith, ‘Progress Report on Guggenheim Fellowship, 1950–1951’ and ‘Application for Renewal for 1951–52,’ 1951

‘Before letters—consequently words—existed, the artist-sculptor made symbols of objects.’

David Smith’s life as an artist was an exploration. Rather than a linear path, from a starting point to an ultimate destination, its trajectory, intentionally dynamic, was akin to a journey comprised of ever-widening circles investigating a galaxy. Smith was born in rural Indiana in 1906. His childhood and development were defined by the transformation of the agricultural Midwest of the nineteenth century to the fully industrialized world of the twentieth. Smith was equally comfortable in the abandoned factories and train yards as in the farm fields that surrounded them in his home in Decatur. All of these spaces were undoubtedly charged for the young boy, his understanding of them forged by images. Smith’s highly visual nature, something that he understood in a primitive way even as a child, led him to seek out a life as an artist.

Sculptures installed in the fields surrounding Smith’s house, Bolton Landing, 1964 © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: David Smith

Access to art and art making were unavailable to Smith during his formative years in Indiana and, later, Ohio. Following graduation from high school in 1924, he set out to discover how he could become an artist, and to grasp what that would even mean. His quest would lead him to Ohio University for just two unsatisfactory semesters; a summer job on an automobile assembly line in South Bend, Indiana; a brief stop at Notre Dame University; and to poetry classes at George Washington University, in Washington, D.C.

In 1926, Smith arrived in New York City and met the artist Dorothy Dehner, whom he would marry the following year. A few years older, and from a more worldly background, she introduced him to the Art Students League, where he was mentored by older artists John Sloan, Jan Matulka, and John Graham, through whom he became part of a circle of young artists that included Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, and Stuart Davis. By joining this small community of young contemporary artists, Smith finally entered the nourishing and inspiring new world he had long sought. Yet it would be the maturation and ascension of his own unique identity, apart from these contemporaries—coupled with an innate confidence and a deeply humanistic belief in the creative act—that would eventually position him as an influential force in twentieth-century art. In the early 1950s, Smith recounted his early experience in New York City’s art scene of the 1930s with great clarity:

'One did not feel disowned—only ignored and much alone, with a vague pressure from authority that art couldn’t be made here. It was a time of temporary expatriates, not that they made art more in France but that they talked it, and when here were happier there; and not that their concept was more avant than ours but they were under its shadow there and we were in the windy openness here.' —David Smith, ‘The Atmosphere of the Early Thirties,’ 1952

The nature of his description is telling, particularly his use of spatial metaphor. Energized and inspired by what was going on in Paris, he felt that artists of his generation working in Europe were ‘under’ the shadow of a collective pressure whereas, in New York, he and his contemporaries experienced an ‘openness.’ That openness allowed for a freedom to invent oneself, inspired by the developing maturity of modernism, but not overpowered by its presence.

'The most important thing to know is who you are and what you stand for, and to acknowledge this identity in your time. You cannot go back. Art cannot go back. The concepts in art are your history, there you start. The projection beyond your filial heritage is as vast as the past. The field for ideas is open and great, your heritage is universal your position is equal to any in the world.' —David Smith, ‘I Sat Near My Window,’ 1953

The sense he shared with an intimate community of young artists that anything was possible was a gift that allowed him to flourish in the belief that he was not held to any standard but his own—not that of the ancient Greeks, the artists of the Renaissance, the American Scene painters, or followers of the latest avant-garde ‘ism’ from Paris.

‘You cannot go back. Art cannot go back. The concepts in art are your history, there you start.’

'Provincialism or coarseness or unculture is greater for creating art than finesse or polish. Creative art has a better chance of developing from coarseness and courage than from culture. One of the good things about American art is that it doesn’t have the spit-and-polish that some foreign art has. It is coarse. One of its virtues is coarseness. A virtue can be anything, as long as that conviction projects an origin—and fresh courage. As long as it has the fire.' —David Smith, ‘Memories to Myself,’ 1960

Having lived through World War I, the Great Depression, the rise of fascism in Europe, World War II, and the postwar emergence of American economic centrality, Smith was part of the generation that defined the full maturity of American art. Numerous exhibitions have been mounted to try and parse and segment his achievement in hopes of presenting it in a way that would communicate the grandeur of his essential contribution to modern art within manageable contexts. This has been a difficult task, as the totality of his life’s work, tragically abbreviated when he died in an automobile accident at the age of fifty-nine, is very difficult to grasp in its breadth and diversity. It does not fit into neat chronological or stylistic periods, nor does his personal vision form a clear narrative. His career cannot be understood episodically and cannot be neatly defined by the various series of works he produced. His output can best be described in his own words, as a ‘work stream’ or as ‘related clues.’

'There are no rights and wrongs. The more you meet a challenge, the more your potential may become. The one rule is that there may be no rules! The only thing you are accountable for is what you do and what you make with it and the good things sometimes are a hazard and the bad things attributes. It’s the person and the individual and what they do with themselves. I think the minute I see a rule or a direction or a method or an introduction to success in some direction, I’m quick to leave it or I desire to leave it . . . The idea of satisfaction is a little like the idea of happiness. It’s the great American illusion.' —David Smith, interview with Thomas B. Hess, 1964

David Smith, Untitled, 1958–59. © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Christopher Burke

David Smith, Three Circles Related, 1958–59 © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth.

‘My concept of an artist is a revolt against the well-worn beauties in the form of a statue. Rather I would prefer my assemblages to be the savage idols of basic patterns, the veiled directives, subconscious associations, the image recall of orders more true than the object itself, resulting in vision, in aura, rather than object reality.’ —David Smith, ‘The Language Is Image,’ 1952

Many of the assumptions that have been built around Smith’s work can be misleading and have served to obscure his complexity and the central principle that guided him. It is often recounted that he was the pioneer who, upon seeing reproductions of the first welded constructions of Pablo Picasso and Julio González, understood that his brief experience as a welder and riveter in a car factory gave him a means and identity with which he would open up the possibilities for sculpture through the use of welding, and industrial process and materials, laying the groundwork for the industrial directness of Minimalism and the expanded ambition that sculpture could be anything. In addition, however, Smith was also a considered craftsman who relished the potential of traditional materials like bronze and oil paint, and delved deeply into the subtle poetics that they embody. Furthermore, he believed in the social necessity and shared availability of content, but his work did not, as some assume, evolve from figuration or surreal content, as in his powerfully political ‘Medals for Dishonor’ (1938–40), to a focused, more simplified geometry.

With a distinct grammar of movement, weights, and balance, Smith created totems for the twentieth century that reflect a conciliatory merging of imagery from nature and industry.

Early on, he firmly believed that abstract visual structure has meaning, and he produced some of his most non-objective abstractions, such as ‘Construction’ (1932), within his first years as a sculptor, as well as in some of his final pieces. He also consistently explored visual references to nature and the human body in diverse ways: in works that are enlivened by surrealist fantasy as well as in some of his most geometric compositions. With a distinct grammar of movement, weights, and balance, Smith created totems for the twentieth century that reflect a conciliatory merging of imagery from nature and industry. The artist Robert Motherwell put Smith’s contradictory nature in poetic terms at the time of his death, eulogizing, ‘Oh David, you were as delicate as Vivaldi and as strong as a Mack truck.’

‘The works you see are segments of my work life. If you prefer one work over another, it is your privilege, but it does not interest me. The work is a statement of identity, it comes from a stream, it is related to my past works, the three or four works in process and the work yet to come. I will accept your rejection, but I will not consider your criticism any more than I will concerning my life.’ —David Smith, ‘The New Sculpture,’ 1952

The diversity and contradictions in Smith’s oeuvre are not incidental, nor are they the result of a restive spirit. Smith was powerfully focused on a central creative impulse: to generate meaning through interconnection. This can be seen in a literal sense in his use of constructive methods that include welding iron sculpture, as well as the accumulation of gesture and form in his paintings and drawings. It can be seen in the ways he synthesized the concerns of sculpture, painting, and drawing. More important though was his deeply personal need to connect himself with a larger history, with deeper universal meanings, and to produce art that would manifest the assertion of these connections. It is considered a principle of Modernism that the past is rejected— only the new, the transgression of expectation has value. This led most artists of the twentieth century to constantly refine their aesthetic focus to the point of a singular vision. Counter to this approach, Smith had an intense need to embrace, interpret, and express a broad range of visual inspiration, and manifest his humanist belief that the history of creativity is a continuum that he was a part of. He believed that committing as an individual to this shared human endeavor held the greatest potential for an art that would most deeply impact our lives.

‘Unity of Three Forms’ (1937) and ‘Reclining Figure’ (1935) at Bolton Landing, ca. 1937 © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth.

‘Culture is not a discovery, an authoritative claim or a premeditated act. It is cumulative, built on the past, contributed to by creative forces indigenous to the people, the age. It progresses with free men. It degenerates with dictation.’ —David Smith, ‘Modern Sculpture and Society,’ ca. 1940

‘Art has its tradition, but it is a visual heritage. The artist’s language is the memory from sight. Art is made from dreams, and visions, and things not known, and least of all from things that can be said. It comes from the inside of who you are when you face yourself. It is an inner declaration of purpose, it is a factor which determines artist identity.’ —David Smith, lecture, Ohio State University, 1959

Smith’s generosity of spirit and humanist ethic were founded in his self-assurance that his originality—his identity—would shine forth more rather than less through his cumulative, expansive vision. This led him to avoid repetition. He abandoned the sculptural practice of editions, making each sculpture a unique expression, through his own action, of the moment of its making. Even in the works he designated as ‘series,’ such as the Agricolas, Tanktotems, Sentinels, and Voltris, there is an expansive conceptual, formal, and visual range.

Smith: I never think of my series as variations on a theme. That’s not in my lexicon. Kuh: If they’re not variations on a theme, what are they? Smith: They’re continuous parts of my concept. —David Smith, interview with Katharine Kuh, 1962 The diversity of Smith’s work excited and confounded his contemporaries. He was clearly not interested in repeating himself or in creating a signature style that would ‘brand’ him as an artist. Smith: I’m always contradicting the known factors. That’s a conscious attitude that I try to develop. Hess: And that’s fighting a style, isn’t it? Smith: I would say so. A fight against my own style, my own yes. . . . I think the minute I see a rule or a direction or a method or an introduction to success in some direction, I’m quick to leave it—or I want to leave it. —David Smith, interview with Thomas B. Hess, 1964

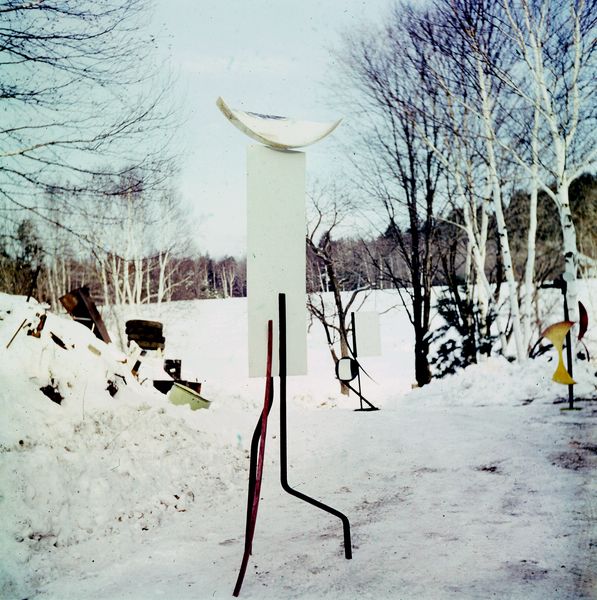

‘Tanktotem IX’, ‘Tanktotem VII’, and ‘Tanktotem VIII’ (1960) in snow at Bolton Landing, ca. 1960 © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth.

David Smith, Untitled (Ship montage), ca. 1930 © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth.

Smith’s refusal to settle into comfortable and successful strategies or to repeat himself was based on a strong work ethic and the sense that his journey was a quest that did not allow for rest. He was, however, very reflective about the risks he took, understanding that an artist must stand for something.

'I find it very hard to explain what I stand for, what my identity is. My identity is not over, because every work of art is part of my identity and it changes, and once I identify myself in a given direction I no longer identify there. I move to another.' —David Smith, interview with Thomas B. Hess, 1964

Unity was a central theme for Smith. And for him, unity, as well as meaning, was accessed most powerfully in a work of art visually. Through the act of making art, Smith expressed his deep need for connection. As his individual works join disparate elements, both literally and metaphorically, to form a whole, so he believed that his accumulated body of works, each with its insistent individuality, made by his hand, presented a larger whole that was the sum of who he was. In fact, it is the image of Smith’s fields that surrounded his home and studio in the remote Adirondack hamlet of Bolton Landing that conveyed to many during his life, as well as to generations that have followed, the wildly fecund variety and animated presence of his diverse output. The unity that was essential to him allowed for no distinction between his perception of who he was and the art that he made. He knew that his work, grounded in his own time, also admitted him to inclusion in the larger expanse of history. Smith freed himself from any existential doubt through his belief that the microcosm of his own humanity as a subject, if acted on with unflinching commitment to exploration, would equal the macrocosm of human potential.

‘To understand a work of art, it must be seen and perceived, not worded. . . . The actual understanding of a work of art only comes through the process by which it was created—and that was by perception.’

‘Art is a paradox that has no laws to bind it . . . either the material substances from which art is made or the mental process of its concept. It is created by man’s imagination in relation to his time. When art exists, it becomes tradition. When it is created, it represents a unity that did not exist before.’ —David Smith, ‘Abstract Art in America,’ 1940

‘The eidetic image, the after-image, is more important than the object. The associations and their visual patterns are often more important than the object.’ —David Smith, ‘To Make a Mark,’ 1955

One of Smith’s innovations was his insistence on the visual nature of sculpture. Traditionally sculpture had dealt with mass and the object as it exists in space. For Smith, the object was an image. The understanding of a three-dimensional work could be constructed by the viewer only if extended through the process of interpreting multiple images of his works. These multiple images, rather than coalesce into a whole, present a kind of journey. The artwork manifesting that journey is not only an expression of the artist’s identity in its purest form, but gives the viewer an active experience of his or her own. Smith’s work prioritizes the engagement between the viewer and the work, not as an object, but as a shared experience. It was not the understanding of the object that Smith offered, but the opportunity for engagement with it, triggering associations and meanings for each viewer that connected his or her humanity with his.

Smith understood that all meaning was contingent, that all forms and materials carried the weight not only of historical and psychological associations, but of purely subjective ones as well. It was this subjectivity that the artist sought to communicate by connecting with his viewers—even referring to his “identity” as the sole content of his work. The resulting objects were deemed ‘new unities.’ Smith was against a ‘style’ that for him would mean limitation. In his mind, there was no singular “answer” in art. Nor was he interested merely in ‘the question.’ Instead, Smith asserted multiple, assured answers that were not only open to individual interpretation, but altogether demanded it.

‘To understand a work of art, it must be seen and perceived, not worded. . . . The actual understanding of a work of art only comes through the process by which it was created—and that was by perception.’ —David Smith, lecture, Williams College, 1951

Sculptures installed in the fields surrounding Smith’s house, Bolton Landing, 1964 © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: by David Smith

In addition to his material process, Smith’s desire to connect disparate parts to make a new and meaningful whole led him to layer references both within and between different works. For this reason, the artist’s oeuvre did not unfold in a linear manner over the course of his life. He continued throughout his career to build on myriad influences and constantly circled back to his earliest inspirations, reconfiguring compositional themes, interweaving natural imagery and universal geometries, and shifting the expectation of media. Smith never abandoned elements he had once identified with, either from art or from the world around him, and although he avoided repetition, he was not afraid to revisit earlier pieces with a fresh eye and expanded ambition.

Smith drew from a multitude of sources, from the prehistoric markings found in caves, man’s first attempts at pictographic language, the indigenous arts and traditions of cultures across the globe, to the contemporary popular illustrations, clippings from newspapers, and other widely disseminated forms of media. Smith found such references to be entirely valid points of inspiration, so much so that they became important parts of who he was as an artist and as a person. The radical innovations of the first generation of European modernists had arguably freed Smith, who felt their achievements formed his rightful heritage.

‘There was no beginning—art was, and what art is now, was and is an expressive need, along with the origin of man. The history of art contains much guesswork and reconstruction, which change with excavation and hypothesis. But the urge to make art, and to respond to art, are constants in man’s evolution. . . .

In one respect the contemporary artist is placed in the outlook of primitive man. He may not distinguish so closely between the realm of man and the realm of nature. He is not the modern scientific man to whom the natural world is ‘it.’ He is more the man who is an element of the phenomena of nature and regards nature more as a ‘thou’ than an ‘it.’

When his painting or his sculpture pours forth, it flows from the inside with all the forces and realities in nature.' —David Smith, ‘The Modern Sculptor and His Materials,’ 1952

Smith’s belief that through his art he could connect with his viewers was central to his conviction that art was the most potent form of communication.

Like Freud, Marx, and Einstein, whose ideas had become the most influential of his time, Smith believed that there were answers. The role of the artist was not simply to ask challenging questions, but to put him- or herself on the line and propose a point of view. For Smith, however, there was no one truth—no unified theory. Affirmation was expressed in the act of making each work, and in its visually resonant presentation of a cumulative sense of history and personal experience. Smith was not a theorist, but a maker who, opening himself to the past as well as to the present, refused to be limited by any preexisting notion of what art could be. Smith’s belief that through his art he could connect with his viewers was central to his conviction that art was the most potent form of communication.

'People wanting to be told something, given the last word, will not find it in art. Art is not didactic. It is not final; it is always waiting for the projection of the viewer’s perceptive powers. Even from the creator’s position, the work represents a segment of his life, based on the history of his previous works, awaiting the continuity of the works to follow. In a sense, a work of art is never finished.' —David Smith, lecture, Williams College, 1951

Installation view, ‘David Smith. Origins and Innovations’, Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street, 2017 © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth

‘I start with one part, then a unit of parts, until a whole appears. Parts have unities and associations and separate afterimages—even when they are no longer parts but a whole. The afterimages of parts lie back on the horizon, very distant cousins to the image formed by the finished work.

The order of the whole can be perceived, but not planned. Logic and verbiage and wisdom will get in the way. I believe in perception as being the highest order of recognition. My faith in it comes as close to an ideal as I have. When I work, there is no consciousness of ideals—but intuition and impulse. To identify no ideal—to approach each work with new order each time.' —David Smith, ‘Notes on My Work,’ 1960

It is, perhaps, counterintuitive to end this brief introduction by circling back to address something as basic as Smith’s material process. But ultimately, Smith was a maker, one for whom the hands-on ‘work’ of making art was essential. Smith was intent on synthesizing an art that could challenge the accepted assumptions that separate the way we approach a drawing, a painting, or a sculpture. For him, any work of art, no matter what the medium, was the result of physical action that emanates from the some source point, and all communicate through vision. For Smith, the primary impulse of art was drawing.

'Drawing is the most direct, closest to the true self, the most natural liberation of man—and if I may guess back to the action of very early man, it may have been the first celebration of man with his secret self—even before song.' —David Smith, ‘Drawing,’ 1955

Drawing is a clear record of human action. Beyond this, however, Smith placed great importance on the associative power of materials, and carefully considered them for each specific work, giving attention to both what they look like and what they represent. Beginning in the early 1950s he used a medium of his own invention, combining the yolk of an egg with India ink. This viscous medium, egg ink, gives many of his works on paper a uniquely lively feeling of physicality and a sculptural sense of depth.

Additionally, the final surface of each sculptural work was of highest importance. For example, as the gloss of an automotive enamel contrasts with the sensuality of artist’s oils, so the contexts that they signal are significantly different. The industrial functionality of the former and the historically rich tradition of the latter were as relevant to Smith as the recuperative statement of reconfiguring abandoned iron tools into a constructed drawing in space.

Installation view, ‘David Smith. Origins and Innovations’, Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street, 2017 © The Estate of David Smith. Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth

This exhibition offers a wide range of materials, each specifically chosen and utilized by the artist for its multiple meanings, but ultimately to resonate in the mind’s eye of the viewer, and to slow the process of looking to the point of intimate exchange. Looking back after decades of work, Smith described how he first formulated the breakdown of the boundaries in the context of his own development.

‘I belong with painters, in a sense, and all my early friends were painters because we all studied together. And I never conceived of myself as anything other than a painter because my work came right through the raised surface, and color and objects applied to the surface. . . . I painted for some years. I’ve never given it up. I always—even if I’m having trouble with a sculpture—I always paint my troubles out.’ —David Smith, interview with David Sylvester, 1960

‘The first constructions that grew off my canvas were wood, somewhere between 1930 and 1933. Then there was an introduction of metal lines and found forms. The next step changed the canvas to the base [of the sculpture]. And then I became a sculptor who painted his images.’ —David Smith, interview with Katharine Kuh, 1962

Paul Cummings wrote the following in the catalogue for the exhibition ‘David Smith: The Drawings’, which he organized for the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1979; it could be extended to describe Smith’s entire practice, whatever the medium:

‘With these drawings, a dichotomy exists; pure drawing and drawing infused with intentions of resulting sculpture battle. Pure drawing relates to Smith’s persuasive gesture for its own pleasure. His penchant for the offending strength of the vulgar implies the need of new criteria by which to judge not only his accomplishments, but those of his contemporaries. What was brash or irritating or lyrical provoked him. The pleasant and the passive were rejected, implying discoveries made and accepted. He manifested the desire of the explorer, delving into his psyche at whatever the cost. He could not limit his drawings to plans for the formulation of sculpture. His imaginative exercises place the drawings amongst the most adventuresome made by a mid-twentieth-century sculptor.’

With this exhibition our intention is to bring into focus David Smith’s artistic origins and some of the diverse innovations that marked his life’s work. While not a retrospective view, the selection of pieces aims to share intimately interwoven connections as Smith expressed them, without prejudice to scale or medium, and to prioritize the visual interrelationships that open a door to who Smith was as an artist, and serve as an invitation to cross that threshold to join him on his exploration.

‘Does the onlooker realize the amount of affection which goes into a work of art—the intense affection—belligerent vitality—and total conviction?’ David Smith, ‘Aesthetics, the Artist, and the Audience,’ 1952

– This text was written on the occasion of the exhibition ‘David Smith. Origins and Innovations’ at Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street, 13 November – 23 December 2017.