Teachers’ Notes: Gustav Metzger

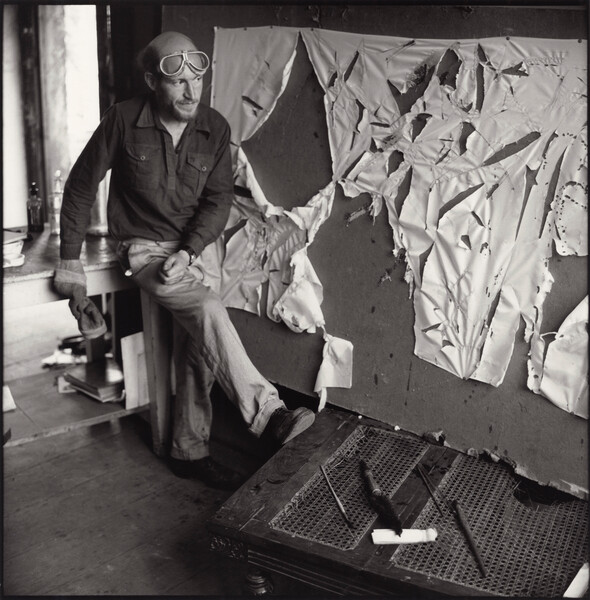

Gustav Metzger practicing for a public demonstration of Auto-destructive art using acid on nylon possibly by John Cox, for Ida Kar, 1960 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Teachers’ Notes: Gustav Metzger

This resource has been produced to accompany the exhibition ‘Gustav Metzger’ at Hauser & Wirth Somerset from 26 Jun – 12 Sep 2021.

About Gustav Metzger

‘Gustav Metzger remains a moral compass, a constant reminder that integrity comes at a price, and that fighting for your convictions can indeed change the world. Metzger has done more than raise awareness. His art and philosophy are a stark testimony to the alternative world for which he strove.’–Mathieu Copeland Gustav Metzger was an artist and political activist who developed the concept of Auto-Destructive Art and the Art Strike. At the heart of Metzger’s practice was a passionate engagement with the notion of creation as a continual counterpoint to themes of destruction. This exhibition will look at works that explore nature, man-made environments and human intervention. Gustav Metzger was born in 1926 in Nuremburg, Germany to a Polish-Jewish family.

In 1939, at the age of 12, Metzger and his brother were evacuated from Germany to England on the ‘Kindertransport’. He lost his parents and most of his immediate family to the Holocaust. In his youth he decided to become ‘a kind of revolutionary’, but after living for six months in a Trotskyist-anarchist Commune in Bristol, Metzger decided this wasn’t what he wanted. He was later convinced to attend life-drawing classes by Henry Moore, after asking to be his assistant and went on to study in Cambridge, Oxford, Antwerp and London. Metzger was the chief proponent of the Auto-Destructive Art (or ADA) movement and organised the DIAS (Destruction in Art Symposium) in 1966 with contemporaries such as John Sharkey.

Other notable attendees and contributors were members of the Fluxus movement and Yoko Ono, who performed her seminal participatory ‘Cut Piece’, where members of the audience were invited to gradually snip away her clothing using a pair of fabric scissors. Metzger dedicated much of his life and career to campaigning for environmental issues, nuclear disarmament and expressing his distaste for consumerism and the wider capitalist agenda. He lived and worked in East London until his death in 2017 at the age of 90. Hauser & Wirth began representing the Estate and Foundation of Gustav Metzger in 2020.

What are the major themes and influences within Metzger’s work?

Auto-Destructive Art

Auto-Destructive Art was designed to highlight mankind’s destructive power and was particularly informed by Metzger’s experience of the Second World War. As a child in Germany, Metzger had watched the National Socialists march through his hometown and this became a formative and recurring memory for him. Metzger held the firm belief that mankind held unparalleled destructive potential and dedicated much of his life to resisting this.

Metzger performed his first outdoor public demonstration of Auto-Destructive Art in 1961 on the Southbank in London, where he donned a gas mask and sprayed acid onto sheets of nylon in the colours red, white and black, which he dissolved before the crowd. Other works include ‘Mobbile’ (1970/2017), a mobile sculpture consisting of a car with a transparent cube affixed to the roof into which a pipe fed exhaust fumes from the vehicle’s engine, slowly suffocating a live plant as it was driven around.

Installation view, ‘Gustav Metzger’, Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2021 © The Estate of Gustav Metzger and The Gustav Metzger Foundation. Photo: Ken Adlard

Auto-Creative Art

In contrast to his use of destruction in art, Metzger was interested in themes of creation and growth, coining the term ‘Auto-Creative Art’ to refer to artworks using technology and machines to create new works. One such example is ‘Liquid Crystal Environment’ 1966/2021, shown in the Rhoades Gallery. Metzger used a computer to heat and cool liquid crystals placed between two plates of a glass, with the psychedelic results projected onto large screens. This technique was later used to create visuals for British band The Who, whose guitarist Pete Townsend was taught by Metzger and cited him as an influence.

Gustav Metzger, Supportive, 1965–1966 / 2011 © The Estate of Gustav Metzger and The Gustav Metzger Foundation. Collection du Musée d’art contemporain, Lyon. Photo courtesy MAC Lyon. Photo: Blaise Adilon

Art Strike

In 1974 Metzger issued a call for artists to withdraw their labour from the system of production for a minimum of three years, which was intended to cripple the system and bring about social change. At the time, Metzger was critical of the use of art for social change or revolution and of artists engaging with political struggle for being too ‘reactionary’. He believed withholding labour was the only way to bring about real change within society. Although he never used the term, this action would be later associated with the wider ‘Art Strike’ movement.

What do Metzger’s works look like?

The Bourgeois Gallery will span three important bodies of work from the 1950s until 2006, including: early paintings and drawings (circa 1950s), Acid Nylon painting (1960/2004), and later works on paper which he called ‘portraits of landscapes’, depicting the nature he saw around him (2003–2006). Several of Metzger’s early paintings and drawings were made on found, readymade materials such as cardboard packaging, magazine and newspaper pages. The furious, jagged marks appear as if he was attacking the canvas with a physicality that reoccurs later in his acid paintings of the 1960s.

Gustav Metzger, Untitled, 1958 – 1959 © The Estate of Gustav Metzger and The Gustav Metzger Foundation. Photo: Theo Niderost

What other artists does his work relate to?

Joseph Beuys (1921 – 1986)

Joseph Beuys is regarded as one of the most influential leaders of avant-garde art in Europe in the 1970s and 1980s. He was appointed Professor of Sculpture at the Kunstakademie in Dusseldorf in 1961, but was dismissed in 1972 after his teaching methods had around conflict Gustav Metzger, Untitled, 1958 – 59. Gouache on paper. 63 × 43 cm / 24 3/4 × 16 7/8 inches. Photo: Theo Niderost © The Estate of Gustav Metzger and The Gustav Metzger Foundation. Courtesy The Estate of Gustav Metzger and Hauser & Wirth with authority. The protests that followed included a strike by his students. He is best known for his performances, of which the most famous was probably ‘How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare’ (1965).

David Bomberg (1890 – 1957) David Bomberg, sometimes described as a ‘blazing radical’, is regarded as one of the most significant twentieth-century British artists. He had a reputation for audaciously going against the grain in typical avant-garde fashion, and his inclination towards creative independence was passed on to his pupils who included Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff, and Gustav Metzger.

Jean Tinguely (1925–1991) Swiss sculptor and experimental artist, whose work was concerned primarily with movement and the machine, satirizing technological civilisation. His ‘Homage to New York’ (1960) blew itself up at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1960, watched by a distinguished audience.

Hermann Nitsch (b. 1938) Nitsch is an Austrian avant-garde artist who works in experimental and multimedia modes. In 1966 Metzger was fined £100 for ‘organising a lewd exhibition’ thanks to ‘Orgies Mysteries Theater’, a performance piece in which the Austrian artist Hermann Nitsch bathed in a vat of animal blood.

Martin Creed (b. 1968) Creed is a British artist, composer and performer. He won the Turner Prize in 2001 for exhibitions during the preceding year, with the jury praising his audacity for exhibiting a single installation, ‘Work No. 227: The lights going on and off’, in the Turner Prize show.

Franz West (1947–2012) West was an Austrian artist who is best known for his unconventional objects and sculptures, installations and furniture work which often require an involvement of the audience.

GLOSSARY

Art Strike

Art Strike refers to a variety of activities where artists refuse to contribute to the capitalist system through withholding their labour and denying ‘production’.

Auto-Creative Art

A term coined by Gustav Metzger to refer to the artworks he made using machines and technology which were inspired by growth and creation.

Auto-Destructive Art

A process of creating artworks inspired by humankind’s ability to destroy. Metzger’s most famous contribution to art history.

Bertrand Russell

Russell was an English academic and polymath who alongside Metzger was arrested for inciting acts of non-violent public disobedience in protest for Nuclear Disarmament in 1961.

Committee of 100

The Committee of 100 was a British Anti-War group set up by Bertrand Russell and others in 1960, who encouraged their followers to commit non-violent acts of public disobedience to protest against war and nuclear weapons.

Consumerism

The preoccupation of society with the acquisition and promotion of consumer goods.

DIAS

The Destruction in Art Symposium, or DIAS, was an event held in London in 1966 initiated by Gustav Metzger. It was attended by artists, poets, scientists and representatives of counter-culture who gathered to discuss the theme of destruction in art and society.

Fluxus

Fluxus was an international, interdisciplinary community of artists, composers, designers and poets during the 1960s and 1970s who engaged in experimental art performances which emphasised artistic process over finished works.

Left Wing

Left Wing is the radical, reforming, or socialist section of a political party or system.

Marxism

Marxism refers to the economic and philosophical principles of Karl Marx whose theories, along with those of Friedrich Engels, led to the formation of Left-Wing political movements such as Communism and Socialism.

Nuclear Disarmament

The movement calling for nations to abandon nuclear weapons, whose ultimate aim was to pressure international governments to agree a treaty prohibiting their creation and use.

Suggested themes for discussion:

Debating the Issues

Students can discuss the topical issues raised in the exhibition with a partner or the whole class. This could include the environment, climate change, consumerism or nuclear disarmament. A simple game in which a statement relating to an issue is described and explained to the whole class, such as

‘Art is a meaningful form of protest’

‘Climate change is the greatest threat in human history’

‘Electric cars are impractical’

‘Everyone should be vegetarian’

‘Nuclear energy is the solution to the overconsumption of fossil fuels’

‘Single use plastics should be banned’

‘Solar power is the energy of the future’

‘We need to take better care of the planet’

‘We buy too many clothes’

A line marks the classroom in half. The left-hand side of the line is for those who disagree with the statement, and the right-hand side is for those who agree, with the marked out middle line being reserved for those who are undecided. Students position themselves according to the strength of their belief for or against the statement i.e. the further way the stand from the middle lien, the stronger their response. A ball is thrown from one pupil to another to give the opportunity to share the reasons for their position, after which students can adjust their location if their minds have been changed. Students from Central Saint Martins join Gustav Metzger’s worldwide call for a Day of Action to Remember Nature, 2015, London, UK. Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Serpentine Galleries

Extended Discussion Points

How can art be used to protest? What issues did Metzger highlight that are still relevant today? How did Auto-Destructive Art defy power structures? How do self-destructing artworks reject capitalist notions of production? Design your own Auto-Destructive artwork Metzger believed that a true auto-destructive artwork must

Return to a state of nothingness within 20 years

Be one where the artist has no ownership, involvement or control over the artwork after they set the work off

Happen or be placed in a public space

What would you make your artwork out of? How would it eventually become nothing? How would you set it off? Where would you put it? Would your artwork have a message? How would you feel about destroying your own work of art?

Supplemental Research

Gustav Metzger Frieze, an interview with Gustav Metzger Another Mag, interview between Gustav Metzger and Karen Orton

Resources

1 / 10