‘Ellen Gallagher’s Biosphere: Ecstatic Draught of Fishes’ by Carol Armstrong

Ellen Gallagher, Watery Ecstatic, 2021 © Ellen Gallagher

‘Ellen Gallagher’s Biosphere: Ecstatic Draught of Fishes’ by Carol Armstrong

I want to start with that blushing watercolor octopus. It looks like something from another world, an interstellar spaceship with a mass of blinking lights, hovering before descending into the watery world below it — or is it rising, floating away, about to depart and return from whence it came? Below it, in the bottom right corner of the large vertical piece of stained, thick-laid paper that forms its watercolor environment, there lies coiled a second cephalopod, this one more amorphous than the first and shading from a blood red to a darker maroon as it appears to sleep, the slit of its one visible eye closed, amidst a green and tangled world of subaquatic vegetation into which some of its ruddy coloring seems to have dissipated, like a pink-hued version of the ink that such creatures are known to expel, or like a beating heart bleeding out. Together, the pair might be understood as a kind of allegory for the different but interwoven dimensions of Gallagher’s practice: its blend of oceanographic natural history and Black-Atlantis mythology; its ecstatic wateriness and its richly generative relation, at once abstract and figurative, to its material ground; and now, its colorism.

To begin with the oceanographic part of the equation, the octopus has long fascinated. As Charles Darwin wrote to a friend in 1832, about ‘several specimens of an Octopus’ that he had collected in the Cape Verde Islands, it ‘possessed a most marvellous power of changing its colours; equalling any chamaelion, and evidently accommodating the changes of the colour of the ground which it passed over — yellowish green, dark brown and red were the prevailing colours…’ [1] A ‘lone survivor from an earlier world,’ the octopus was also the ‘spectator of all,’ swimming above the settled substrate of the sea-floor below, according to the Hawaiian account of the ‘drama of creation,’ as charted by the anthropologist-mythographer Roland Dixon in 1916.

In 1955, Rachel Carson wrote thus about the Florida Keys ecosystem in which the octopus participated: In the islands of turtle grass many animals find food and shelter. The giant starfish, Oreaster, lives here. So do the large pink or queen conch, the tulip band shell, the helmet shells and the cask shells. A strange, armor-encased fish, the cowfish, swims just above the bottom, parting grass blades to which pipefish and sea horses cling. Baby octopuses hide among the roots and when pursued dive deep into the yielding sand and disappear from view. Down in that grass-root underturf many other small beings, of diverse kinds, live deep within the shadowed coolness, to come out only when night and darkness hide them… [2]

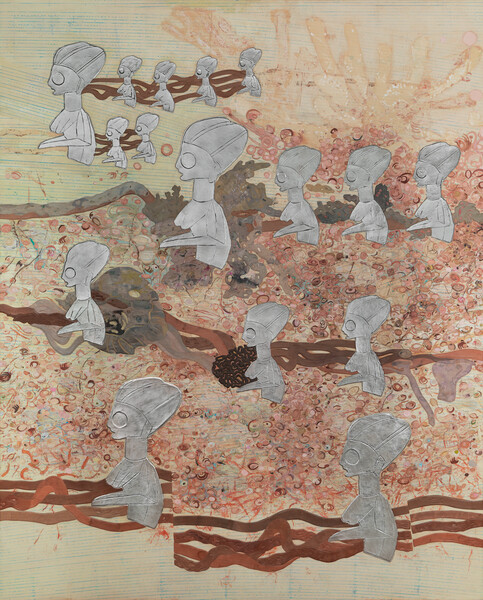

Ellen Gallagher, Ecstatic Draught of Fishes, 2021 © Ellen Gallagher

And then, in 2016, the Australian philosopher of science Peter Godfrey-Smith wrote about the octopus as an anti-hierarchical model of consciousness diffused across an entire body, itself more akin to a community of communicating organisms than a single, bounded, humanoid individual. [3] At the same time, the octopus, its relatives, and its fantastical derivatives have featured in science fiction, from Jules Verne’s 1870 novel 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, to the tentacled aliens in Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis (Lilith’s Brood) trilogy of 1987-89.

More immediately germane to Gallagher’s work, however, is the nautical Afro-futurist myth of ‘Drexciya,’ invented by the Detroit techno-band of the same name in 1997, and made up of a mutant population descended from the unborn children of African women thrown overboard during the centuries-long ‘Middle Passage’ slave trade. Since 2001, the series Watery Ecstatic, and now the new series of paintings, Ecstatic Draught of Fishes, which began in 2019, have been concerned with that mythic underwater ecosystem: the new octopus watercolor, which is part of the longerstanding series, belongs to that preoccupation. Within that context, the octopus is one of those organisms that, in its otherworldliness, straddles the boundary between scientific fact and fiction.

Ellen Gallagher, Ecstatic Draught of Fishes, 2020 © Ellen Gallagher

From the beginning, the Watery Ecstatic series has included an entire Middle Atlantic bestiary, part ‘Drexciya’ fiction and part zoological and botanical fact: not only octopus, but also eels, fish, jellyfish, whales, sea serpents, icythosaurus, nautilus shells, sea urchins, seaweed- and coral-resembling tangles have long comingled, sometimes painted with a mixed-media brew of watercolor, pencil, gesso, ink, varnish, egg tempera, crushed mica, gold leaf, plasticine, polymer medium, sometimes sculpted out of the paper support, sometimes both.

That world often includes diminutive female heads, as if sprouted like underwater spawn ‘[d]own in that grass root under-turf,’ as in one large vertical variant made in 2018, while another variant from the same year produces a world of phantom seaweeds sprouting polyp-, egg- and seed-like forms. It is notable that when exhibited in S.o Paulo’s MASP, the latter was hung in between two similarly sized vertical portraits of Brazilian Africans, man, woman and child, by the Dutch 17th century painter Albert Eckout: entered into dialogue with the Eckout portraits, the Watery Ecstatic piece proposes its watery, multiorganism verticality and its fact/fiction hybridity as an alternative to the latter’s equally vertical and apparently naturalistic anthropocentric singularities.

[5] Meanwhile, the newer series of paper-and-canvas paintings, Ecstatic Draught of Fishes — three have so far been made — is even more explicit in its generating of a Drexciyan bio-mythology out of its material substrate: incised palladium-leaf caryatids, inspired by sculpted Fang figurines, burgeon from out of Gallagher’s signature ground of pasted sheets of handwriting paper, to proliferate amidst swarms of seaweed-, egg- and fish-like forms, like the mythic children of Black Atlantis. At the same time, other variants of the Watery Ecstatic series, along with other free-standing paintings, pursue the more abstract side of Gallagher’s practice, and in the process foreground both the materiality and the colorism of the stratum from which figuration emerges in her work.

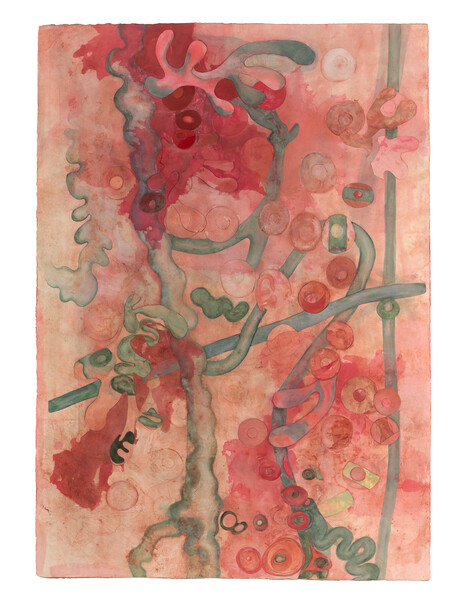

One of the other more recent Watery Ecstatic pieces shares both its agua viva wateriness and its red-and-green color scheme with the octopus watercolor with which I began, minus the figurative distinctness of the octopus duo, and spatially reoriented so that it is as if we look down on the flat, fossilized floor of the deep, from the unearthly point of view of that ancient ‘spectator of all.’ [6] Or perhaps it is more close-up than that suggests: a tangle of unnameable spores and filaments that look something like what you might see in a much-enlarged microscope slide. Or both: in any case, we are made to see with other eyes, gazing down upon the undersea terrain from which life is born.

Ellen Gallagher, Watery Ecstatic, 2021 © Ellen Gallagher

That same terrain conflates its topos with its materiality, making the modernist distinction between figuration and abstraction obsolete. Not only does the watercolor medium itself blend its own literal wateriness with the wateriness of its referent, Gallagher’s method of working her ground by staining, digging and cutting into it to excavate its thickness, serves to emphasize its sedimented aspect both literally and figuratively: the ground of the octopus watercolor, in particular, has a creased and undulating look to it — a wavering, materialized grid of organic, brain-like folds that generates a whole world of ideas and images.

And then, the palette of these works — consisting of historical pigments with fabulous names such as Burgundy Ochre, Venetian Red, Gubbio Red, Bohemian Green Earth, Green Earth from Verona, Russian Earth, and Bluish Green Earth Cyprus — bears down on the doubled aspect of that ground, and on the global dissemination and temporal layering of its liquid/solid earthiness. In short, if Gallagher’s work thus lands on the colorist, binary-collapsing side of the old colore-disegno divide, it does so as an octopus might: by ‘accommo-dating the changes of the colour of the ground which it passe[s] over.’

Ellen Gallagher, Paradise Shift, 2020 © Ellen Gallagher

Having begun with the octopus, let me end with one large, free-standing painting painted in between the first and second Ecstatic Draught of Fishes: Paradise Shift. This painting returns us to the abstractionist idiom from which Gallagher’s Watery Ecstatic and related series emerged: with its flattened, earthen-colored textile effect, Paradise Shift resembles a fringed flying carpet, or an overhead map spattered with squirming protozoa and a dark shape that, having mutated from out of something like Malevich’s Black Square, might further mutate into anything.

In that newest painting, figure has gone back to ground, ‘chamaelion’-like, and that ground — here more dry land than underwater bed in its texture and palette — looks all set to birth yet other extra-terrestrial worlds. Paradise Shift serves to punctuate the deliberate interweaving of the figurative and the abstract that constitutes Gallagher’s work, pointing to the way that dialectic works within the specific unfolding of individual series as well as in the relationships among different series, and more generally, within the imaginative to and fro between image-invention and its material foundation.

The exhibition ‘Ellen Gallagher. Ecstatic Draught of Fishes’ is on view at Hauser & Wirth London from 21 May – 31 July 2021.

[1] Letter of May 18, 1832, from Rio de Janeiro, in Extracts from Letters addressed to Professor Henslow by C. Darwin, Esq. (Read at a Meeting of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, Dec. 1, 1835), privately printed, 1960, pg. 4.[2] Rachel Carson, The Edge of the Sea (1955), Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin, A Mariner Book, 1998, pg. 231.[3] Peter Godfrey-Smith, Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016. (The quote from Roland Dixon, above, is taken from the epigraph to Other Minds.)[5] On this exhibition, see Adriana Pedrosa, Historias Afro-Atlanticas, S.o Paolo: MASP, 2018.[6] For the literary equivalent of the liquid dynamics of Gallagher’s work, see Clarice Lispector, Agua Viva (1973), Stefan Tobler, trans., New York: New Directions, 2012.

Resources

1 / 10