Jakub Julian Ziolkowski at Hauser & Wirth NY reviewed by ARTFORUM

Installation view, 'Jakub Julian Ziolkowski. Timothy Galoty & The Dead Brains', Hauser & Wirth 69th Street, New York, 2010. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Josh Nefsky

Jakub Julian Ziolkowski at Hauser & Wirth NY reviewed by ARTFORUM

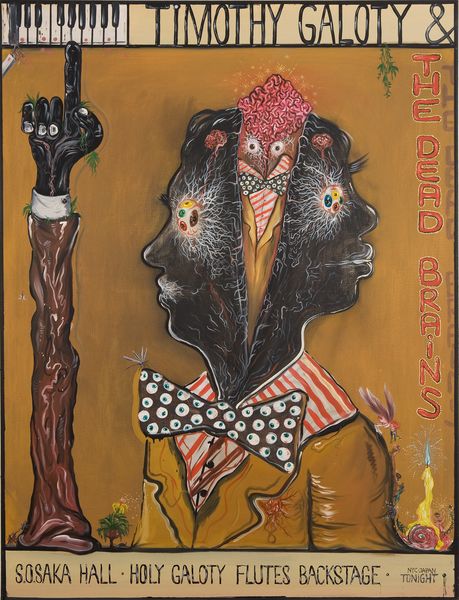

With the painting ‘Timothy Galoty & the Dead Brains’ (all works 2010), Jakub Julian Ziolkowski has invented a surreally raucous, somewhat wild-eyed band of performing artists, apparently based on a fantasy heavy metal band.

Galoty, an imaginative surrogate for Ziolkowski, is divided against himself, as his split head, featuring two faces in profile, suggests. One, more pugnacious visage has blubbery lips and a small face; the other, marked by tight lips and a larger face, is relatively handsome. Both have the same electrifying eyes – sort of lurid white jellyfish, each with streamers of tentacle-like nerves emanating from their red rims and inset with four brightly colored irises that glow like gems.

This Janus-faced figure wears a large white collar with red stripes, as well as an oversize bow tie, which is colored the same deep-shit brown as the head and also gleams – and teems – with eyes (each possessing only one emerald-like iris). Emerging from the head’s fissure, and looking straight at us, is a small replica of Galoty – clearly his brain, which seems more alive than dead, as suggested by its huge mass of red tissue, surrounded by a twinkling eye-star aura.

But the point of the whole work seems to be Galoty’s raised finger: Unlike the raised finger of John the Baptist in Leonardo’s painting, the message of Galoty’s black finger, which resembles an erect penis, is ‘up yours,’ not ‘look up.’

Jakub Julian Ziolkowski, ‘Untitled (OMABO)’, 2010. Photo: Thomas Müller

Jakub Julian Ziolkowski, 'Timothy Galoty & The Dead Brains', 2010. Photo: Josh Nefsky

‘Up yours’ seems to be the whole nihilistic, pessimistic, sardonic, stick-it-to-you point of Ziolkowski’s paintings. ‘Untitled (Into the Hole)’ makes this unequivocally clear: The whole world is draining into an abyss – a black asshole. A cartoony Raft of the Medusa appears in the picture, with a priest – he looks as though he stepped out of a George Grosz caricature – as a sort of prow, suggesting that it is a ship of fools.

There are in fact numerous art-historical quotations in Ziolkowski’s works: ‘Untitled (OMABO),’ for instance, features a mockingly slapdash take on Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes; in an untitled allover painting, the signature eyes become polka dot–like gestures; the existentially serious ‘The Clash’ is based on Goya’s ‘Fight with Cudgels’ – a painting in which two figures battle to the death while standing knee-deep in the quicksand (rendered as shit) in which both will drown.

Indeed, on one level Ziolkowski’s work seems like a wide-ranging parodic reprise of modernist ideas, as the paintings’ surrealistic figuration and expressionistic energy indicate. Both tendencies are brilliantly integrated – scrambled? – in Caligula. The flamboyant weirdness, not to mention sensationalist candor, with which Ziolkowski wields modernist staples suggests that he thinks they are the best way to revivify age-old themes: the triumph of death, as conveyed by his various skeletons, some a discombobulated collection of dancing bones; and the triumph of human folly, evident in ‘Priceless Arse,’ a rendering of a bent-over man who shits gold coins.

Indeed, scatology tends to serve a critical purpose in Ziolkowski’s works. His scathing comic morbidity is oddly refreshing, perhaps because it breathes new life into modern-type art and into the theme of death. But he can also be very unfunny. See, for example, the agonized face in ‘Untitled’ – its mouth open in death or a scream, its eyes covered in coins. Many of Ziolkowski’s paintings have a posterlike blatancy; one four-part suite, ‘Galoty (Posters # 1–4),’ comprises explicit poster paintings.

A rendering of a skeleton photographer – an attack on photography by a painter – is also blunt and outspoken. But, as ‘Milk & Honey’ shows, Ziolkowski can also be coy and insinuating. Overall, the artist’s work seems heavily dependent on German art – on Hans Baldung Grien’s death imagery, Neue Sachlichkeit’s sense of social absurdity, and German neo-expressionist black humor – in its vision of the human condition. An unholy and disturbingly deranged face in Untitled (King of Israel) suggests the unsettling complexity of Ziolkowski’s mentality. Whatever its ideological implications – and however it caters to controversy – it is a fine, surreally expressionistic painting that might be an alternative self-portrait to Timothy Galoty, if as barbaric.

Related News

1 / 5