An Army of One: A Conversation with Richard Jackson

Richard Jackson, The War Room, 2006 – 2007 © Richard Jackson. Photo: Joshua White

An Army of One: A Conversation with Richard Jackson

Wiping his beleaguered hands over the table like temperamental car wipers, ageing American artist Richard Jackson reclines in his seat for the length of the interview, in a manner befitting a man drawing breath from a prolonged pursuit for recognition.

Jackson is a veteran of the west coast, where he originally shared an apartment in Los Angeles with performance artist Bruce Nauman. And he recalls at the time, how they drew inspiration from one another; in a determined attempt to replace the franchised interests of modern art for something gustier.

Drawn on the dynamism of American art, Jackson goes no further than Nauman, whom he regards as possibly the most important contemporary artist to have lived in the modern era. Insisting how ‘we all owe something to him, everyone.

I mean you can’t deny it, can’t say you were doing it at the same time, not true.’ Yet at the same time it is impossible not to draw comparisons between the grandiose spirit and scale of artists like Paul McCarthy, Mike Kelly, and Ed Ruscha; with his own work. As a generation of artists who profited from conceiving of a messier aesthetic.

Yet in spite of such collateral commonality, for Jackson everything is his own. ‘What is of interest to me is not how things are the same, but how they are different. This doesn’t have to lead to this, it could just lead to nowhere.’ And at its fractious nucleus Jackson’s artworks have always propositioned a perverse alternative to the pedestrian pattern of things. That could well be likened to tipping a heavily ladened table over onto the floor, in order to revel in the damaged disarray thereafter.

His is a glorious celebration of failure, as it determines all of his decision making. Propositioning work that is as likely to collapse under the weight of expectation of an audience; as it is likely to perform perfectly well. And for all of the misanthropic energy harboured at the institutional interests of art; Jackson embattled and bitter, recalls something of the spirit of Fluxus artist Joseph Beuys. Who revelled in the ‘difficulty of explaining things,’ and whose performative work was governed entirely by the gravitas of the moment, in the shape of ‘the happening.’

For Jackson the happening is his entirely, as he professes to enjoy the anticipation in his works of something greater. ‘I think I don’t like to do (the performative element of the work) publicly. Because what I am trying to do is a number of things. I want to stimulate people’s imagination, because then the event becomes bigger.’ Yet in spite of such criticality as context, Jackson appears inexhaustible deterred by the critical isolation he suffered up until now.

Jackson was making art for several decades; working in construction and teaching college students, before receiving any kind of recognition. And he professed to feeling as frustrated by those protracted circumstances, as he was determined to remain on the fringes of contemporary culture. Less interested in idle semantics, the crux of what Jackson has attempted to do for many decades now, is in allowing there to be ‘evidence of an activity or performance’ within his work, as he describes it; and crucially conjuring an ‘activity’ that is ‘without any kind of audience.’

As his choreographed silicone, steel, electronics, paper and paint, perform in a gratifying misadventure of tampered objects as art. Critically prior to his 2013 Hauser & Wirth solo show, he details how ‘the last show was three years ago, and before that I didn’t show for twenty years in Los Angeles. There was absolutely no suppose, and there still isn’t. I have no commercial support. I have a lot of attention now, but showing commercially in Los Angeles, never going to happen.

I will never get any success from that. Never. And what I realised it is like hitting yourself with a hammer. It feels good when you stop.’ Recognising that the merit of any commercial success was challenged entirely by his own actionist approach to art, Jackson has always operated as an army of one, who eulogises failure; not only as a remedy for his own failings to some extent, but also as a necessary alternative to the routine of success. And for that he is as compelling an artist as Bruce Nauman has become.

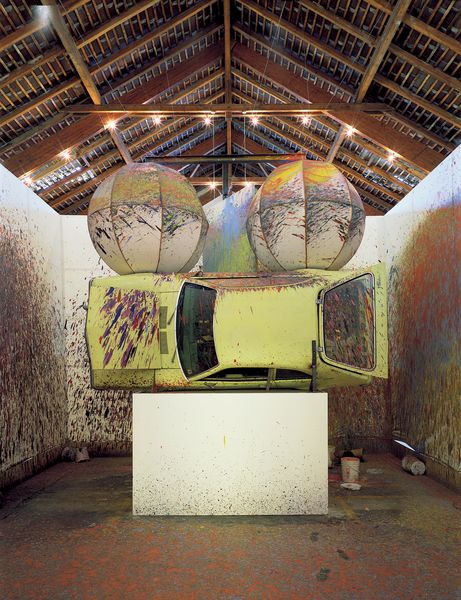

Richard Jackson. Painting with Two Balls, 1997 © Richard Jackson

I want to stimulate people’s imagination, because then the event becomes something bigger. A lot of my work is about scale, in relation to one person. I am interested in what one human being can accomplish on their own.

Richard Jackson: I think there are a lot of younger artists trying to revisit Abstract Expressionism to some degree. (For me) abstract painting never went anywhere. I mean I have some in my hotel room, and there’s all kinds of varying levels of accomplishment and so on. But is almost just become like elevator music. Nobody looks at it, nobody listens to it.

Rajesh Punj: Were such visual limitations a point of departure for you?

RJ: I think there is nothing more with Abstract Expressionism. I think the thing is that when you get involved in a project you should learn something from that experience. You know it might be minor, but you should set up in a way that you can learn something. Often at times I learn something from other people, because my project takes me to other people for advice. Or help or whatever, and so I think that with painting and stylising your work at some point you can’t learn anything from it anymore. It’s like those wall paintings upstairs (for Hauser & Wirth), it’s like forty years ago I did that work, and periodically I do it again. Not because they ever sell or anything, I have never sold any. But whenever I do it in a public exhibition, I don’t learn anything from it. I finished one here this morning; I did half of it last night and half of it this morning, I didn’t learn anything. There is no surprise there.

RP: Are you having to educate your audience to ‘new ways of looking’ at your work?

RJ: I think other people educate my audience; because people see what I have done, and what other people are doing, and it makes more sense now. You know I just wear them down, (the audience). The one thing if you are there long enough people will say, ‘oh my god this guy is not going away.’ I mean it’s like this group of artists in Los Angeles, who were doing really well in their thirties. One of them came to me and said, ‘you know we were talking about you the other night.’ And this was when I was in my forties. I was older than them. And they said ‘we don’t understand you but we think you are serious.’ It was kind of shocking. But I think if you hang around for long enough you become something.

RP: You draw on a fundamental point with your work, of the notion of the ‘event,’ and of the evidence as exhibited material. Why are your audience privileged to part of a work, and not given it in its entirety?

RJ: I think I don’t like to do (the performative element of the work) publicly. Because what I am trying to do is a number of things. I want to stimulate people’s imagination, because then the event becomes something bigger. A lot of my work is about scale, in relation to one person. I am interested in what one human being can accomplish on their own. I am not interested in corporate studios with fifteen employees. I am really not interested in that. I am not surprised if the government, with all its people and all its money, can orbit the earth. But if somebody can do that on their own then I am interested. I mean if somebody in their backyard can fool around and call back on their cell phone ‘I am in orbit,’ I am into that. Because the individual is not so important, that’s why everybody is on facebook and all that stuff.

RP: You touch on something incredibly significant, which is the notion of the ‘army of one.’ Of your being independent of everyone else, in order you can produce original work. Can you explore that?

RJ: It might not be as big an accomplishment as a group could do, but it is about scale. I made that piece with ‘1000 Pictures,’ and I made that all by myself. I made all the wood, I stretched all of the canvases. I primed it all, I painted it all. I stacked them all. I did it all by myself. And that has a different sense about it. The same with ‘1000 Clocks,’ I made every single part of those clocks. And I hand assembled them in my house. I worked all day in construction, and came home at night, and then I made them. And I made them by hand. And there are forty-four thousand parts and connections to that thing. And I got it to go you know. Like it goes, it works. And it is a thousand clocks exactly, and what you do is you take this thing, which is a big task for yourself. But somehow you get it done. And then because the piece was already made, was supposed to be in ‘Helter-Skelter,’ the exhibition. As one of the primary sort of pieces. There were three primary pieces, and mine was one. And the reason was because those three pieces were done by those three artists. And it (‘1000 Clocks’) had never run before. And I put it together on the spot, and I made it work. Well of course about twenty-five of the clocks didn’t work. And I had to go in every morning at five in the morning and reset, and run the bugs out of this thing so that it would work. And the thing was, was that basically the curators and the museum were not happy about the whole thing. The piece was one of the bigger failures in the exhibition. But none of that was written about, that I had made this thing by hand. Ninety percent of the work in the exhibition was done and paid for by the museum. People come in with an idea, and the exhibitions are sometimes conceived of in the same way as a film. Where there is an idea and you get a producer, and a lot of work is made that way now. So really it is like they come inside with a little tiny model, cut out of a piece of paper, and say that is nine feet high. And so my work just got completely ploughed under, and there was no proper explanation; nothing was written about it.

RP: But is that not the nature of contemporary art having become a forensic experience? In which anything of (Marcel) Duchamp’s original avocation for ‘chance’ has since evaporated.

RJ: When ‘hell breaks loose and things go wrong,’ then you are on the spot. It’s is not like in the studio where you can start over with paint. Or you can do a little something to correct it. Like when you are operating in a situation that I put myself in; there are often times when you have to be creative. Because there are problems that can only be solved creatively. And so I challenge myself you know.

RP: So for you, who were the artists that mattered?

RJ: Well I think Bruce Nauman was important. I have known Bruce since he was twenty years old, and we lived in the same house for five years. He was a close friend for a long time. But aside from that, you are just distancing yourself. Because I do not really see or hear from him that much anymore. He is the greatest artist of our generation, of my generation. And we all owe something to him. Everyone. I mean you can’t deny it, can’t say you were doing it at the same time, not true. And you can see that. Nauman’s work is so different from what it was, and not only that, but the next work could be so different from anything he has ever done. You can never guess what he is going to do. He is so smart. But people have just acquired or taken his aesthetic. Like how things (his works) are put together, so on and so forth. So things that look really rough and crude are actually not at all. He is an excellent craftsman. So things look the way they do because that is how he wants them to look. And it is all different and people adopt that messy aesthetic. Like they have to kind of fake it.

We are having a conversation here, during a period of our conversation a hundred and fifty thousand works of art have been completed around world, and that’s the age we are living in. And so it’s not a sacred kind of thing anymore, and it shouldn’t be. And that’s the thing with my wall paintings. Nothing is forever. Everything has a beginning and an end.

Richard Jackson, Clown, 2013 – 2014 © Richard Jackson. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

RP: What intrigues me is how you define yourself; as ‘actionist,’ ‘artist,’ ‘anarchist,’ or ‘interventionist’?

RJ: Someone else asked me that, and I think I said I was an ‘art terrorist.’ But you know my definition of art is ‘unusual behaviour.’ As soon as you start acting normally in this corporate atmosphere, then maybe you are not an artist anymore. We are a group of people, and this is a job, that’s all it is. Don’t apply any more importance to it than there really is. It is just a job, so don’t try to connect it to something that doesn’t make any sense anymore. Don’t try and connect yourself to Andy Warhol, because that’s not modern. We are living in a modern era, and nothing is sacred in the environment we are in. We don’t own a computer or a cell phone for more than two years. Why do we have to keep all this crap around us? We are having a conversation here, during a period of our conversation a hundred and fifty thousand works of art have been completed around world, and that’s the age we are living in. And so it’s not a sacred kind of thing anymore, and it shouldn’t be. And that’s the thing with my wall paintings. Nothing is forever. Everything has a beginning and an end. Everything has a life and a death. And there is no reason to make these kinds of things based on a certain atmosphere that are cared for and are different. And it would be nice if the work would sell for less money, and then there would be less importance attached to it. Only money does that. And then it could be sort of like short term, and make room for more of it. Like new ideas to come in from younger people, or whoever has new ideas. Instead of the old ideas revisited, and also doctored up; and then you don’t get as much change.

RP: How do you expect an audience to engage with your work?

RJ: They may not be able to relate to it physically. I think that I have a great sense of humour. I think that comes through, and then I also have a certain kind of irreverence. Maybe most people are timid or shy people. Or people who can’t express themselves honestly would enjoy my work. ‘God I wish I could do that.’

RP: Your commercial success hasn’t been as you would have wished; how do you feel about that?

RJ: It’s my fault. The thing you have to do, is that you have to except the consequences for your behaviour. I don’t go in there with the intent that somebody is going to change their attitude and buy anything. This is what I want to do, this is what I want to show people, and this is what I want people to think about. I want them to think about what I do, and I want it to be different from everybody else. Not purposely, because I am different. That’s what I want to do. I don’t think those installations are going to sell. There’s no way in hell. The wall paintings are not going sell. People want me to revisit those wall paintings. If I live another forty years they still won’t sell. Because they don’t fit in. They still don’t fit in. I am so proud of that.

RP: Why was the west coast, and Los Angeles in particular such a difficult place to exhibit for you?

RJ: The last show I had was three years ago, and before that I didn’t show for twenty years in Los Angeles. There was absolutely no suppose, and there still isn’t. I have no commercial support. I have a lot of attention now, but showing commercially in Los Angeles, was never going to happen. I will never get any success from that. Never. And what I realised it is like hitting yourself with a hammer. It feels good when you stop. So I stopped. Because I was financially supporting my own work. Putting up big big projects, like ‘1000 Clocks.’ I made those clocks, I paid for those clocks. It cost me a hundred thousand dollars. Money I made working in construction. And people know who I am, but commercially it’s never going to happen there. A drawing not anything. And yet I am asked to donate drawings for fund-rising things and so on. So it’s not like they don’t know about me. But it’s not going to happen. I don’t show a lot, I just want to make a living. I want to show enough to make a living. Not compromise my work at this point. And I think now I am old enough, and people have enough respect for me to make that happen. But sometimes you wonder. But like I say you have to be willing to except the circumstances that come with your actions. And I am smart enough to know ahead of time that there is no commercial value in this stuff. But I want to make it anyway. Because if I don’t make it, not many people will. And then maybe what I am shooting for is that maybe they will have enough respect for me to take care of me somehow. –

‘Richard Jackson: Unexpected Unexplained Unaccepted’ is a major survey of the artist’s room installations on view at Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt through 3 May 2020.

Related News

1 / 5