Leon Golub at the Serpentine Gallery reviewed by Frieze

Installation view, 'Leon Golub: Bite Your Tongue', Serpentine Gallery, London, England, 2015 © READS 2015

Leon Golub at the Serpentine Gallery reviewed by Frieze

It’s their skin that gives them away. The guys that populate Leon Golub’s paintings – military conscripts, guns for hire, warring giants and cynical cops – all suffer from terrible complexions.

Some are merely sunburned, following a delirious tour of duty in a faraway jungle warzone. Others have raw eyelids and sunken, yellowing cheeks – the product of a bad diet or, perhaps, a bad conscience. Still others have been comprehensively flayed, although this does not trouble their mad, ecstatic grins.

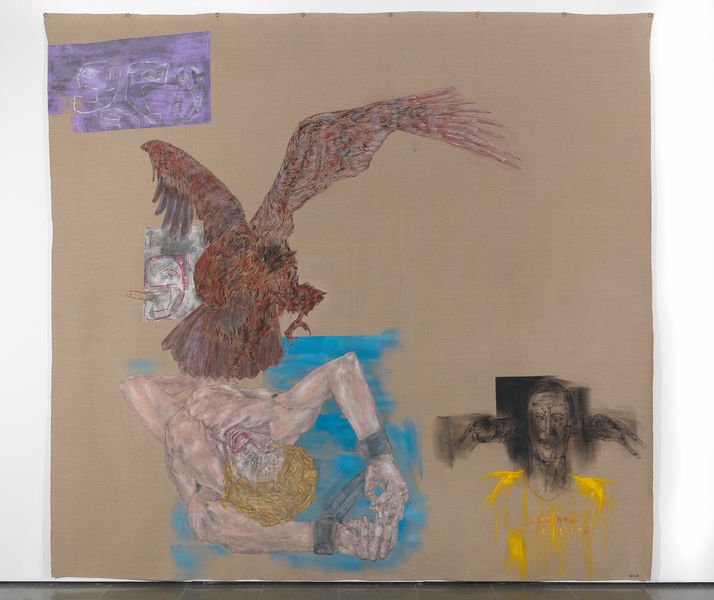

Like skin, paint is an interface, a site where one human being communes with another, and looking at the Serpentine Gallery’s Leon Golub retrospective ‘Bite Your Tongue’ – which ranged from early paintings such his 1962 ‘L’Homme de Palmyre’ (a scabbed colossus) to late works including 1997’s ‘Prometheus’ (a screaming, corn-fed hunk, menaced by a scruffy eagle) – what’s striking is how consistently he used pigment to summon up physical, and spiritual, corruption.

Golub’s paint always has the same dry, slightly tacky quality, like the roof of a dehydrated mouth. The canvases that support it are nearly all un-stretched and, pinned to the gallery wall, they resemble a collection of hideous trophies, hides curing in the sun. SaveSave

Leon Golub, 'Prometheus', 1997 © The Estate of Leon Golub. Photo: AC Cooper LTD

A figurative painter who emerged during abstraction’s ascendance, an artist who used a brush, of all things, to depict TV-age atrocities in Vietnam and Central America, Golub was likewise unworried about drawing from the brackish well of myth. Near the entrance to the show hung ‘Poised Sphinx’ (1964), a fat pupae that later reappeared in ‘Red Sphinx’ (1988), now hatched into a haughty monster, incarnadined with blood. For Sigmund Freud, the real riddle of the Sphinx was: ‘Where do babies come from?’ For Golub it seemed to be: ‘What do babies become?’

The answer, of course, is adults, practiced in the adult stuff of power and violence. In the Serpentine’s rotunda, several paintings from the artist’s extraordinary ‘Mercenaries’ and ‘Interrogation’ series, produced in the early 1980s, loomed high on the walls, like an accusation. In ‘White Squad IV (El Salvador)’ (1983), a baseball-hatted goon has just loaded a dead body into a car. Turning towards us, his hand clasped around his pistol, he seeks our intimidated assent.

This man, as the painting’s title suggests, is a member of one of the CIA-sponsored death squads active during the Salvadoran Civil War although, like the brutal, brutalized torturers of Interrogation III (1981) (one of whom, in a lurid detail, wears the heavy gold watch of a man well-rewarded for his labours), we might imagine him plying his trade more recently, on the streets of Iraq or Afghanistan, in Abu Graib or Guatánamo, or in any number of ‘black sites’ across the globe. ‘The Go-Ahead’ (1985–86) spirits us to the back room of a police station, its walls seemingly slicked with excrement, where a posse of schlubby officers have been given the green light to do who-knows-what.

One hand cupping his balls, the central figure stares out at us with a bloodshot eye, seemingly asking: ‘Hey, you in?’ We all are, whether we like it or not, and looking at Golub’s painting we experience our complicity like an itch, or like a sour taste in our mouths.

Leon Golub, 'Mercenaries II (section I)', 1975 © The Estate of Leon Golub. Photo: Andrew Smart, AC Cooper LTD

Text features heavily in works made close to the artist’s death in 2004: rants from froglike cyborgs, a busted skeleton musing ‘Man! I’ve Got to Get Myself Together!’ (2004), a torturer ambiguously bellowing ‘This Could Be You #2’ (2001) as he thumps and kicks.

Not quite gallows humour, this is rather waterboard humour – unbearable, and with no end in sight. Several commentators on the Serpentine show have expressed astonishment at Golub’s contemporaneity. What would really astonish is if these fevered, nightmarish canvases felt long ago and far away.

Related News

1 / 5