An Interview with Eva Hesse

Eva Hesse, ‘Repetition Nineteen III’, 1968 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

An Interview with Eva Hesse

First published in ARTFORUM in 1970, this rare interview with Cindy Nemser gives insight into Eva Hesse’s practice, totality in her commitment to making art and absurdist influences from Duchamp to Yvonne Rainer, all captured in the last year of her life.

Cindy Nemser: Do you identify with any particular school of painting?

Eva Hesse: I don’t think I ever did any traditional paintings – except what you call Abstract Expressionism. I most loved de Kooning and Gorky, but that was personal – not for what I could take from them. But I know the importance of Kline and Pollock and now I would say Pollock before anyone, but I didn’t feel that way when I was growing up. Oldenburg is an artist that I really believe in. I respect his writings, his person, his energy, his art, the whole thing. He has humor, and he has his own use of materials. But I don’t think I’ve taken or used those materials in any way. I don’t think I’ve ever done that with anybody’s work. To me, Oldenburg is wholly abstract. The same with Andy Warhol. He too is high on my favorite list … He is the most as an artist that you could be. His art and his statements and his person are so equivalent. He and his work are the same. It is what I want to be, the most Eva can be as an artist and as a person … I feel very close to Carl Andre. I feel, let’s say, emotionally connected to his work. It does something to my insides. His metal plates were the concentration camp for me.

CN: If Carl knew your response to his work what would be his reaction?

EH: I don’t know! Maybe it would be repellent to him that I would say such a thing about his art. He says you can’t confuse life and art. But I think art is a total thing. A total person giving a contribution. It is an essence, a soul, and that’s what it’s about … In my inner soul art and life are inseparable. It becomes more absurd and less absurd to isolate a basically intuitive idea and then work up some calculated system and follow it through – that supposedly being the more intellectual approach – than giving precedence to soul or presence or whatever you want to call it … I am interested in solving an unknown factor of art and an unknown factor of life. It can’t be divorced as an idea or composition or form. I don’t believe art can be based on that. In fact my idea now is to counteract everything I’ve ever learned or been taught about those things – to find something that is inevitable that is my life, my feeing, my thoughts. This year, not knowing whether I would survive or not was connected with not knowing whether I would ever do art again. One of my first visions when I woke up from my operation was that I didn’t have to be an artist to justify my existence, that I had a right to live without being one.

Eva Hesse, Ennead, 1966 © The Estate of Eva Hesse. Photo: Abby Robinson, New York

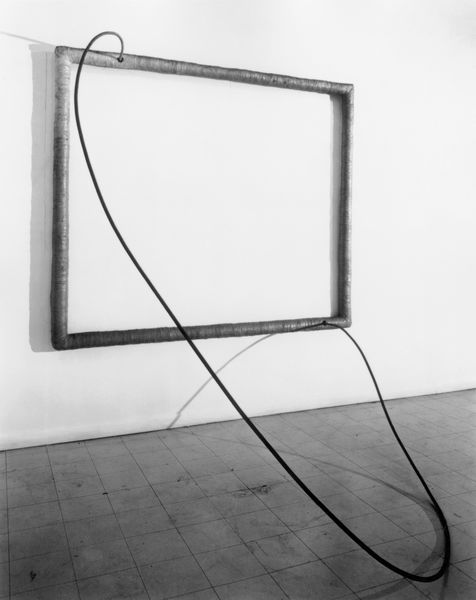

Eva Hesse, Hang Up, 1966 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

CN: How do you feel about craftsmanship in the process of your work?

EH: I do think there is a state of quality that is necessary, but it is not based on correctness. It has to do with the quality of the piece itself and nothing to do with neatness or edges. It’s not the artisan quality of the work, but the integrity of the piece … I’m not conscious of materials as a beautiful essence … For me the great involvement is for a purpose – to arrive at an end – not that much of a thing in itself … I am interested in finding out through working on the piece some of the potential and not the preconceived … As you work, the piece itself can define or redefine the next step, or the next step combined with some vague idea … I want to allow myself to get involved in what is happening and what can happen and be completely free to let that go and change … I do, however, have a very strong feeling about honesty – and in the process, I like to be, it sounds corny, true to whatever I use, and use it in the least pretentious and most direct way … If the material is liquid, I don’t just leave it or pour it. I can control it, but I don’t really want to change it. I don’t want to add color or make it thicker or thinner. There isn’t a rule. I don’t want to keep any rules. That’s why my art might be so good, because I have no fear. I could take risks … My attitude toward art is most open. It is totally unconservative – just freedom and willingness to work. I really walk on the edge …

CN: How do the materials relate to the content of your work?

EH: It’s not a simple question for me … First, when I work it’s only the abstract qualities that I’m working with, which is the material, the forms it’s going to take, the size, the scale, the positioning, where it comes from, the ceiling, the floor … However I don’t value the totality of the image on these abstract or esthetic points. For me, as I said before, art and life are inseparable. If I can name the content, then maybe on that level, it’s the total absurdity of life. If I am related to certain artists it is not so much from having studied their works or writings, but from feeling the total absurdity in their work.

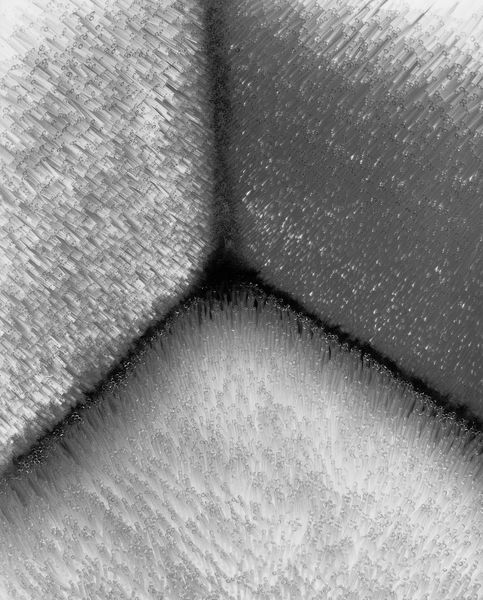

Eva Hesse, Accession II, 1968 (1969) © The Estate of Eva Hesse. Hauser & Wirth. Photo: John A. Ferrari, New York

Eva Hesse, Accession II (detail), 1968 (1969) © The Estate of Eva Hesse

CN: Which artists? Marcel Duchamp, Yvonne Rainer, Jasper Johns, Carl Andre, Sartre, Samuel Beckett …

CN: Absurdity?

EH: It’s so personal … Art and work and art and life are very connected and my whole life has been absurd. There isn’t a thing in my life that has happened that hasn’t been extreme – personal health, family, economic situations. My art, my school, my personal friends were the best things I ever had. And now back to extreme sickness – all extreme – all absurd. Now art being the most important thing for me, other than existing and staying alive, became connected to this, now closer meshed than ever, and absurdity is the key word … It has to do with contradictions and oppositions. In the forms I use in my work the contradictions are certainly there. I was always aware that I should take order versus chaos, stringy versus mass, huge versus small, and I would try to find the most absurd opposites or extreme opposites … I was always aware of their absurdity and also their formal contradictions and it was always more interesting than making something average, normal, right size, right proportion …

CN: How about motifs, the circle for instance? You used it quite frequently in your early work.

EH: I think that there is a time element in my use of the circle. It was a sequence of change and maturation. I think I am less involved in it now … In the last works I did, just about a year ago, I was less interested in a specific form like the circle or square or rectangle … I was really working to get to a non-anthropomorphic, non-geometric, non-non … When I came back from Europe, about 1965 – 66, I did a piece called Hangup. It was the most important early statement I made. It was the first time my idea of absurdity or extreme feeling came through. It was a huge piece, six feet by seven feet. The construction is really very naïve. If I now were to make it, I’d construct it differently. It is a frame, ostensibly, and it sits on the wall with a very thin, strong but easily bent rod that comes out of it. The frame is all cord and rope. It’s all tied up like a hospital bandage – as if someone broke an arm. The whole thing is absolutely rigid, neat cord around the entire thing … It is extreme and that is why I like it and don’t like it. It’s so absurd to have that long thin metal rod coming out of that structure. And it comes out a lot, about ten or eleven feet out, and what is it coming out of? It is coming out of this frame, something and yet nothing and – oh, more absurdity! – is very, very finely done. The colors on the frame were carefully graduated from light to dark – the whole thing is ludicrous. It is the most ridiculous structure that I ever made and that is why it is really good. It has a kind of depth or soul or absurdity or life or meaning or feeling or intellect that I want to get … I know there is nothing unconnected in this world, but if art can stand by itself, these really were alone. And there was no one doing anything like this at the time. I mean it was totally absurd to everybody. That was the height of Minimal and Pop – not that I care – all I wanted was to find my own scene – my own world – inner peace or inner turmoil, but I wanted it to be mine.

Eva Hesse, Sequel, 1967-1968 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

CN: You did a piece called ‘Ennead’ in 1965 that starts out symmetrical and ends up in a chaotic tangle.

EH: Yes. It started out perfectly symmetrical at the top and everything was perfectly planned. The strings were gradated in color as well as the board from which they came. Yet it ended up in a jumble of string … The strings were very soft and each came from one of the circles. Although I wove the string equally in the back (in the back of the piece you can see how equal they are) and it could be arranged to be perfect, since they are all the same length, as soon as they started falling down, they went different ways and as they got further toward the ground the more chaotic they got … I’ve always opposed content to form or just form to form. There is always divergency … That huge box I did in 1967, I called it ‘Accession’. I did it first in metal, then in fiberglass. On the outside it takes the form of a square, a perfect square, and the outside is very, very clear. The inside, however, looks amazingly chaotic, although it’s the same pieces of hose going through. It’s the same thing, but as different as it could possibly be … But it is a little too precious from where I stand now. It’s too beautiful, like a gem, and too right, I’d like to do a little more wrong at this point …

CN: Why do you repeat form over and over again?

EH: Because it exaggerates. If something is meaningful, maybe it’s more meaningful said ten times. It’s not just an aesthetic choice. If something is absurd, it’s much more exaggerated, more absurd if it’s repeated … I don’t think I always do it, but repetition does enlarge or increase or exaggerate an idea or purpose in a statement … At times I thought, ‘The more thought the greater the art,’ but now I wonder about that … I think there is a lot that I’ll just let happen and maybe it will come out the better for it … Maybe if I really believe in me, trust me, without any calculated plan, who knows what will happen …

CN: You mentioned Duchamp before as an artist you felt close to. Perhaps you are also involved with the element of change, say in a work like ‘Sequel’?

EH: Yes, it’s all loose. It’s at random. The circles can be manipulated at random. The only limitation is the mat and these shapes could roll off the mat because they’re basically cylindrical … The piece is made of half spheres that are rigid. They were cast from half balls and then they were put together again but not completely. They were put together with an opening so that the whole thing was ‘squooshy.’ It was a solid ball but it wasn’t a solid ball, it’s collapsible and it’s not collapsible because it’s rubber, and then it’s cylindrical, but yet it’s not, but the balls could still be moved. The whole thing is ordered but again there’s that duplicity. But this is an old piece and it interests me less of course as a problem. Again that duplicity – before I said I was not interested in formal problems, but ‘Sequel’ obviously represented a formal problem to me.

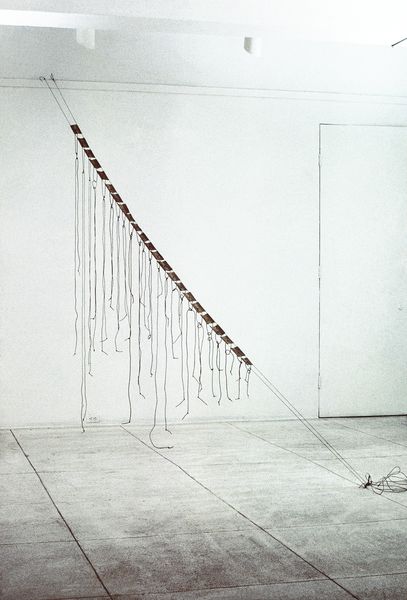

Eva Hesse, Vinculum I, March 1969 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

CN: Is there another work that particularly embodies your impulses towards contradictions?

EH: There is a piece called Area which I did in 1968 that I made out of the mold of another piece which was ‘Repetition 19’. I took the bottoms of the containers and rubberized the forms, attached them, and sewed them together. It’s twenty feet long and I have a personal attachment to the piece. The pieces are totally disconnected. ‘Repetition 19’ was made of empty containers and there was that sexual connotation – it is anthropomorphic. Area isn’t, or is in a totally different way. It is used as a flat piece with a suggestive three-dimensionality. Area is so ugly, I mean the color, ‘Repetition 19’ is clear fiberglass.

CN: Your most recent work seems more free and daring than ever.

EH: I would like to do that now – well, why not? I used to plan a lot and do everything myself. Then I started to take the chance – no, I needed the help. It was a little difficult at first. I worked with two people, but we got to know each other well enough, and I got confident enough, and just prior to when I was sick I would not state the problem or plan the day. I would let more happen and let myself be used in a freer way and they also – their participation was more their own, more flexible. I wanted to see within a day’s work or within three days’ work what we would do together with a general focus but not anything specified. I really would like, when I start working again, to go further into this whole process. It doesn’t mean total chance, but more freedom and openness.

Eva Hesse, Area, 1968 © The Estate of Eva Hesse. Photo: John A. Ferrari

Eva Hesse, Expanded Expansion, 1969 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

CN: Has the new openness changed your work?

EH: I can think of one thing that it changed. Prior to that time, the process of my work used to take a long time. First because I did most of it myself, and then when I planned the larger pieces and worked with someone, they were more formalistic. Then, when we started working less formalistically or with greater chance the whole process became speeded up. When we did one of the pieces at the Whitney that I love the most, the ladder-like piece, ‘Vinculum I’, it took a very short time. It was a very complex piece, but the whole attitude was different, and that is more the attitude that I want to work with now, in fact, even increased, even more exaggerated … That was one of the last pieces I did before I got so ill. It was one of the pieces we started working on with less plan. I just described the vague idea to two people I worked with, and we went and just started doing it. There were a few things that I said to one of the people that I worked with. I said I wanted to make a pole. He made a perfect pole – it wasn’t what I meant at all. So we started again and then he understood …

CN: ‘Vinculum II’ also seems involved with chance elements, particularly in its potential for movement.

EH: ‘Vinculum II’ is connected to the ladder piece in that it is made with the same rubber hosing. But ‘Vinculum I’ is solid and staid and inflexible except for the hose, while ‘Vinculum II’, though very similar, is totally flexible. There isn’t anything that can be staid or put. All these parts can be moved, every connection is movable. So it has a very fragile, tenuous quality. It is very, very taut as it is attached from two angles. There is lots of tension, yet the whole thing is flexible and moves. It’s made of wire mesh with fiberglass and the parts are just stapled so they can really go up and down; they are positioned but they can be moved. And then through the wire and fiberglass is a hole and these irregular robber hoses go through them. They’re all different lengths. Everything is tenuous because the hoses are not really knotted very tight and they can change and I don’t mind it, within reason.

Eva Hesse, Vinculum II, 1969 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

CN: You said you weren’t interested in environmental pieces, yet Expanded Expansion, with its size and presence has an environmental quality.

EH: I guess this is the closest thing I’ve done to an environment. It is leaning against the wall like a curtain and the scale might make it superficially environmental but that’s not enough … I thought I would make more of it, but sickness prevented that – then it could actually be extended to a length one would really feel would be environmental. This piece does have an option … I think that what confuses people in a piece like this is that it’s so silly and yet it is made fairly well. Its ridiculous quality is contradicted by its definite concern about its presentation …

CN: What about ‘Right After’?

EH: I want to tell you about the background of that work. I have to go back a bit, because it’s relative. I started the initial idea a year ago. The idea totalled before I was sick. The piece was strung in my studio for a whole year. So I wasn’t in connectiveness with it when I went back to it, but I visually remembered it. I remembered what I wanted to do with the piece and at that point I should have left it, because it was really daring. It was very, very simple and very extreme because it looked like a really big nothing which was one of the things that I so much wanted to be able to achieve. I wanted to totally throw myself into a vision that I would have to adjust to and learn to understand … But coming back to it after a summer of not having seen it, I felt it needed more work, more completion and that was my mistake. It left the ugly zone and went to the beauty zone. I didn’t mean it to do that.

CN: You found it too decorative?

EH: I don’t want to even use this word because I don’t want it to be used in any interview of mine, connected with my work. To me that word, or the way I use it or feel about it, is the only art sin. I can’t stand gushy movies, pretty pictures and pretty sculptures, decorations on the walls, pretty colors, red, yellow, and blue, nice parallel lines make me sick …

Eva Hesse, Metronomic Irregularity I, 1966 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

CN: _Getting back to ‘_Right After’…

EH: My original statement was so simple and there wasn’t that much there, just irregular wires and very little material. It was really absurd and totally strange and I lost it. So now I am attempting to do it in another material, in rope, and I think I’ll get much better results with this one.

CN: How can you ignore the formal aspects of art?

EH: So I am stuck with aesthetic problems. But I want to reach out past … I want to give greater significance to my art. I want to extend my art perhaps into something that doesn’t exist yet …

CN: Like falling off the edge?

EH: That’s a nice way of saying it. Yes, I would like to do that. – Fragments of the audio recording from this interview are available to listen to as part of the Getty Research Institute’s podcast ‘Recording Artists: Radical Women’ hosted by Helen Molesworth with artist Mary Weatherford and art historian Darby English. A selection of Hesse’s drawings feature in the travelling exhibition ‘Forms Larger and Bolder: EVA HESSE DRAWINGS’. The show continues from Hauser & Wirth, 69th Street to MUMOK in Vienna, where it’s on view through 16 February 2020.

Related News

1 / 5