Thomas Houseago: The Brutal Truth

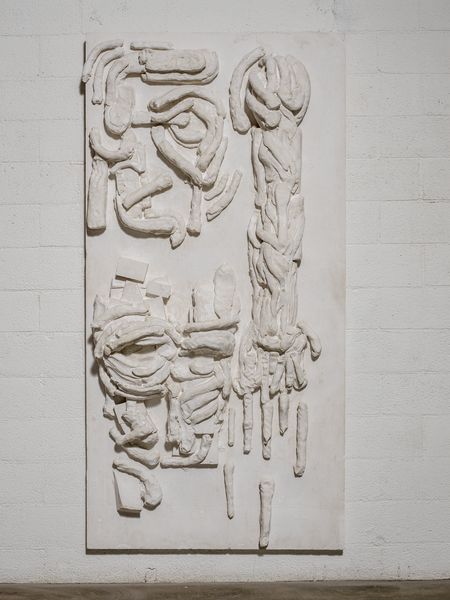

Installation view, "I'll be your sister", Hauser & Wirth London, 2012 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Thomas Houseago: The Brutal Truth

Their plaster skins, still caught gloopy in rough, fluid creation, splosh and slump, splash and splatter. With bent backs and arched legs, they lurch and shamble and trudge. Heavy heads and heavy feet dangle and plod. They do all this without moving a gypsumed finger. Like Roald Dahl’s BFG or Rabelais’s beshitten giants Gargantua and Pantagruel, Houseago’s creations invite words like messy sound effects to explain the unmilled hugeness of their craggy bodies and their plump plaster stillness.

It’s a sloppy stillness. As though nature, when dealing with such sizes, could not design a delicate feature with steady precision. Housego’s creations sometimes give the impression that they’re trying to look back to look forward, to figure out what it means to make a thing in this general mishmash of digital ethereality, exotic financial instruments, after a half-century of conceptual art. Some critics contend that his is regressive, conservative art that looks too readily and consumably like art, while others argue that Houseago is just picking up where others left off – continuing great traditions – and that art isn’t about progress but about expression.

This way, that way. Or as Houseago has cited in more than one interview (including one with this correspondent), Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? – the title of Paul Gauguin’s famous 1897 painting. (Should we even mention the word ‘primitivism’?) Plaster slathers, penciled bits of wallboard and jagged rebar: all of it congealing into a figure. Men and women, monsters and heroes, occasionally animals, aggressively formed: eyes torn out, occasionally decapitated, rusty bones naked, faces roped into masks, bodies contorted into asanas that would make a yogi weep.

The materials for much of Houseago’s oeuvre are the kinds of things one could, in a jam, steal from a construction site: rough, cheap, modern. Materials usually purchased by the pallet by blue-jeaned and work-booted men from mammoth hardware warehouses. Whatever fancy milieu these sculptures find themselves in, they begin – like their maker – in pretty proletarian places. Increasingly replaced with less modest redwood and bronze, the white plastery skin of many of his sculptures, when plunked into one room after another in large exhibitions, look like collections of unearthed classical statues.

Though the Romans were too self-consciously civilized for such beasts, perhaps it’s as if the Goths and Vandals, Angles and Picts, broke into a Roman marble-yard and carved out the likeness of a few of their own deities and monsters to freak out the locals. Of course, for those who like to look at them just so, Houseago’s rough-hewn bodies recall a previous era of sculpture. They wear their skins like cousins to Giacometti’s narrow, turbulent creatures, but don’t look quite so terribly tortured by an anguished and unappeasable creator.

A working girl from Picasso’s Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon (1907) makes a cameo, sculpted and handled into tangibility. A handful of characters from Greek myth stumble bemusedly into the twenty-first century, midwifed into raw bodies by the artist.

Thomas Houseago, ‘Construction I’, 2012 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

Thomas Houseago, ‘Construction I’ (detail), 2012 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

Houseago likely learned a thing or two from more recent artists, too – his former teachers include Marlene Dumas and Thomas Schuütte. Though those two finger forms with different materials, some of their concerns wend their way into the work of Houseago. Both artists deal with bodies – Dumas with the painterly half-light of the direct, salacious stare, and Schütte with sculptural bodies built to suffer, distorted and deformed.

Schütte’s figures still manage to convey some beauty in their deformities, which might have come through hardship or power, doubt or pain, and they reflect the contemporary age in their pallor: a creamy synthetic only viable in the age of spurting machines and their candy-coloured possibilities. Houseago’s hulks can be sexy, but their lust seems less complex than Dumas’s. One sculpture, Cave/Rock Head III (2012), a giant cock and balls with a face carved into it, is patently puerile, but he wouldn’t be the first artist with a penchant for dick jokes (from Salvador Dalí to Paul McCarthy).

While it plays with the appropriate parts, Houseago’s sculptures achieve a much headier concupiscence by more subtle means in other works. In Ghost of a Flea I (2012), the occult mask hides the slinking body of a headless haunt. Its serpentine lurch and smeary skin make for slinking, spectral Peeping Tom or wraithlike Aqualung. While Schütte’s portraits’ suffering has always looked like corporate executives poisoned by greed and pollution, Houseago’s figures look more like those executives’ longsuffering labourers.

(We could insert a biographical note here about Houseago’s birth in the broke-down northern factory town of Leeds or his eventual escape from grey England to sunny Los Angeles.) Busted-out factories and huge smokestacks make their own monuments (see Tate Modern, though Leeds was once littered with them), and like all those brick kilns and steel mills made in a time when objects freighted more meaning and industry more power, Houseago’s sculptures are, self-consciously, monumental; marching with slaggard feet out of coal fields and through silicon valleys.

Thomas Houseago, ‘Ghost of a Flea I’, 2011 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

Standing under some ten-foot figure in his studio (which was swarming with labourers of his own), Houseago told me he still firmly believes in the power of objects and that power can be a good thing. I’m suspicious of monuments and monumental gestures, of power and powerful things. I’m tired of egos trying to carve their names into landscapes, into history, in the biggest possible way, of the cavalcade of dudes who think physical weight equals spiritual gravitas.

And I’m not the only one suspicious of monuments: it was not without some real reason that the curators of the New Museum inaugurated their sparky new building a few years back with an exhibition titled Unmonumental. To set out to make monuments is problematic. Whatever Richard set out to do in making his steel giants, they look like advertisements for industry (and he only uses a trademark variety of steel, Corten; as Houseago lists his plaster under its brand, Tuf-Cal).

Perhaps though, in setting out to make monuments, Houseago hopes to recover some of the shipwrecked optimism of modernity – that things, that art, could change the world. Hokey perhaps, but still hopeful in a way I’m not cynical enough to hate on. A ready trope perhaps this last decade, particularly pronounced before the financial crash, but Houseago’s sculptures feel weirdly confident of the future as they soldier on in a way that, say, the postapocalyptic sculptures of Matthew Monahan do not.

Perhaps it’s a Panglossian optimism, but it’s still backboning his hunched monuments. A little traumatised by all the grandiose notions of the individuals and civilisations that have erected monuments, however, I often prefer the subtle, ephemeral gesture over the raw power of size and weight. But preferences aside, I’m open to the work of Thomas Houseago; others seem less so. Seeing it as conservative or reactionary, perhaps the haters sense Houseago’s rejection of the primacy of conceptualism.

The artist told me tales about coming of age as an artist in early 1990s London, when the YBAs were ascendant and every trust-fund kid in England was trying his princely hand at conceptual art. For him, to make big, heavy figurative sculptures with quick, cheap materials seemed a revolutionary gesture. And 20 years on, his muscular sculptures, with their messy skins and masks, can go too hard into physicality and can sometimes feel almost dunderheaded in their assertion of emotional bodies, formal qualities. Big Baby, from 2010, a sculpture that appeared in that year’s Whitney Biennial, is perhaps a little self-conscious joke on the big-headed crudity and simple, messy joy of his variety of object-making.

Thomas Houseago, ‘Large Owl (For B)’, 2011 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Many writers have called Houseago’s sculptures a return to Modernism, which is true in a way, but Modernism after a century of getting hammered; a Modernism that has had a terrible beating, been smashed by trauma, and which tries to pull its hulking form out of a ramshackle landscape with some sense of humour intact or even gained from its troubles.

Thrown together with many of the same cheap housing materials that eventually took down the global economy, these sculptures have dragged their heavy bodies through a long, hard century to stumble into the Blair and Bush years, and subsequently into one of the worst financial disasters in almost a century. Now that these modernist giants have come, I think some people question if we need them, these lumbering, rough-hewn things, these battered labourers of plaster and steel, shed from abandoned factories and born from tattered ideals.

Though they can smash all the machines that replace them, the labourers turned Luddites, these makers, with their rough hands and facility with things and not abstractions, still have to find a home. Stuck perhaps with no good place to go, they stand with heavy bodies still as statues waiting for a new moment to come.

Related News

1 / 5