Figuratively Speaking: A Conversation with Thomas Houseago

Thomas Houseago, ‘Untitled (Red Man)’, 2008 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, Xavier Hufkens and L&M Arts, Los Angeles

Figuratively Speaking: A Conversation with Thomas Houseago

12 August 2017

Thomas Houseago’s expressionist sculptures, part of a renewed interest in figuration, are popping up everywhere, in one-person and group exhibitions in Brussels, Amsterdam, Milan, London, Glasgow, Paris, Berlin, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, and Marfa.

This fall and winter, both the Rennie Collection in Vancouver and Modern Art Oxford are hosting shows of his idiosyncratically constructed figures. Imbued with contradictory characteristics, Houseago’s works are at the same time abstract and representational, monstrous yet vulnerable, aggressive but somehow casual, animated yet still, three-dimensional but flat, and unfinished looking yet satisfyingly complete.

Mining the depths of art history, he references a myriad of sources, from the arts of antiquity to Rodin, the Modernist sculptures of Brancusi and Picasso, folk art, and non-Western sculpture. He also takes inspiration from music and other forms of popular culture such as cartoons, comics, children’s books, and album covers. Born in 1972, Houseago is of a generation that ‘sees Modernist art through the lens of pop culture, not the other way around.’ His work can convey the reductive quality of a Brancusi, the muscularity and energy of a Rodin, the multiplicity of viewpoints of a Picasso, or the futuristic look of a sci-fi character.

Thomas Houseago, ‘Sprawling Octopus Man’, 2009 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, Xavier Hufkens and L&M Arts, Los Angeles. Photo: Joshua White

Rachel Rosenfield Lafo: You were born in Leeds, UK, and lived in London, Amsterdam, New York, and Brussels before moving to Los Angeles. What took you to these different cities, and what you have found in LA. that has kept you there? Thomas Houseago: Like a lot of artists, I was aware early on that I liked to draw, look at things, and meditate on the world. By the age of four or five, I was processing the world through drawing in much the same way that I do today, even though I had no concept of what an artist was.

Leeds at that time was an incredible place, very tough and broken down, yet very passionate and raw. There was no artistic culture there really, just a culture of drinking and going crazy, in which I took part. Music – the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and later The Smiths – provided me with my first avant-garde perspective. I remember hearing Magical Mystery Tour and being both terrified and thrilled. But I didn’t really have roots or a sense of belonging in Leeds, and I had a strong feeling that it would be impossible for me to become an artist there, so I needed to move on.

I still look back and see it as a miracle that I got accepted to St. Martin’s College of Art and Design in London. It really saved my life, as those last years in Leeds were quite dangerous. So, I set off for London, with a full grant from the government, not really aware that I would be arriving there like Oliver Twist.

Thomas Houseago, ‘Squatting Man’, 2005 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, Xavier Hufkens and L&M Arts, Los Angeles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

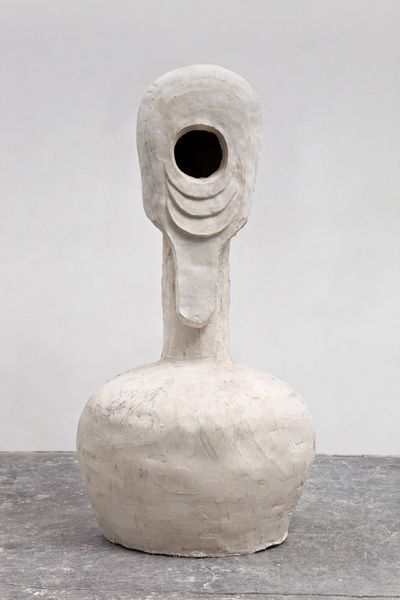

Thomas Houseago, ‘Bottle Head’, 2010 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, Xavier Hufkens and L&M Arts, Los Angeles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

RRL: Did you know anyone there? TH: No. I had only been to London a couple of times in my life; it was really a foreign country to me, a very impressive yet intimidating place. I had never seen such wealth and self-confidence, so it was fascinating and liberating. St. Martin’s was amazing because it was situated on Charing Cross Road in Soho in a beautiful run-down building. The sculpture studio was on the 7th floor, and the view and feeling up there were magical. The studio’s incredible history progressed from a traditional English art school to Anthony Caro and the steel welders to Gilbert and George and Richard Long. But, by the time I arrived in 1991, it was the art school for freaks, which I certainly was.

RRL: What kind of work did you make in school?

TH: I had been doing a weird, primitive kind of performance art in Leeds, which included making objects that I would burn. I was (and still am) heavily influenced by Joseph Beuys and the feeling of urgency in his work. Sculpture had been totally irrelevant to me, but in London, I began to enjoy making things, mainly collections of objects that became environments I liked to be in. I clicked with Enrico David, a fellow student at St. Martin’s, who was making a strange kind of psycho-figuration. But I didn’t make anything that truly excited me until I reached De Ateliers artists’ institute in Amsterdam. That experience was tremendously important for me. There were amazing visiting artists at the time – Jan Dibbets, Stanley Brouwn, Marlene Dumas, Thomas Schütte, Luc Tuymans, and Didier Vermeiren – and you could say that they performed the role of spirit guides. Things just began to pour out of me. I was totally overcome by the need to exorcise myself, and these strange figures/sculptures began to arrive and were a real shock to me. I felt I had no choice but to follow the work and try to understand it wherever it led me. I met Amy Bessone (my wife) there, and we embarked on an odyssey together, which first involved falling down the rabbit hole of Brussels and Belgium. When that started to get too edgy, we were urged by Matthew Monahan (whom we knew from the Ateliers) to come to Los Angeles to join him and Lara Schnitger. We arrived there in 2004 with absolutely nothing, like some crazy pilgrims. We had been through fire that led to a total rebirth. I instantly loved the city of Los Angeles, which has been incredibly good to me, and I can’t imagine working anywhere else.

Thomas Houseago, ‘Striding Man’, 2006 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, Xavier Hufkens and L&M Arts, Los Angeles. Photo: Joshua White.

Thomas Houseago, ‘Striding Man’ (detail), 2006 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, Xavier Hufkens and L&M Arts, Los Angeles. Photo: Joshua White.

RRL: Your work is very historically informed, referencing music, art history, and popular culture. You touch on many sources, from ancient art to Rodin, Picasso, Matisse, Brancusi, Surrealism, German Expressionism, art from native cultures, folk art, and pop culture action figures. Can you talk about your relationship to these styles, movements, and artists?

TH: I have never had a hang-up about art history; I see it as my artistic family, as oxygen. My generation emerged at a time of endings – death of painting, death of the author – and since I come from a place with no sense of culture at all, I had no need or desire to create a false tabula rasa. I truly felt that nothing was possible, yet simultaneously everything was. I wanted to create space, to be absurd and also informed, to try to build. I have always wanted to look at everything. I grew up with an idea of figuration that came from cartoons, movies, and music, and when I discovered Picasso and Brancusi, I saw their work as a way of processing and sublimating what you see in the world. We are in such a strange time now, on many levels, but certainly visually, it is very helpful to look back as well as around or ahead. I also get ideas from fellow artists, such as Amy Bessone, Enrico David, and Aaron Curry.

RRL: Did you come to a combination of abstraction and figuration by looking at Picasso and Cubism?

TH: No, not in a literal way, but, yes, in that his work has influenced the way our world currently looks – and by that, I mean to say that in the West, at least, we are all kind of Cubists now. But I can also say that Bob Dylan, the Beatles, and Neil Young have helped me a lot with that debate, as have Hanna-Barbera and Carl Andre.

RRL: Your work offers a multiplicity of perspectives and combines two- and three-dimensionality. Why do you adopt these shifting viewpoints?

TH: In my approach to making sculpture, I try to be honest to the experience of looking and recording. You could argue that sculpture is a dramatization of the space between your eye and the world, between looking and recording, between what you see and feel and memory. I try to allow as much as possible to happen while I’m working on the piece and yet keep it contained within a single object. That seems to get the most truthful results. I’m not trying to adopt any particular viewpoint, I’m just trying to be true to the way I see and feel. When I look at someone, it’s not in a photographic or filmic way. What I see always seems to break down into a state of flux. Really looking at something is a strange experience, and I want to be realistic about that. My memories of how my body feels affect how I look at someone else. My fantasies also have to be kept in check. Then I transform that experience into an inert material, with an expanded idea about how things really look. In a sense, I see my pieces as very realistic, and I’m sure people sense that when they look at the sculptures.

Thomas Houseago, ‘Mask (black hill/red hill)’, 2008 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, Xavier Hufkens and L&M Arts, Los Angeles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

RRL: I would never have thought to use the word ‘realistic’ to describe your work. Are your sculptures, with their aggressive stances and exaggerated forms, meant to be scary and monstrous? And what about the role of the mask in your work?

TH: I really never try to make monsters, although people can be monstrous and terrifying at times. Perhaps you think of monsters because there is a kind of Frankenstein thing that happens when you try to sculpt or represent a figure. In that sense, all depictions of a person or body in sculpture are quite monstrous. Michelangelo’s David has something really monstrous about it, as do his sculptures for the Medici tomb. The same can be said for Rodin – Balzac is a beast – and even Giacometti if you look through that lens. My main concern is to capture a kind of reality so that the pieces take on an energy or life. The end result of their appearance is very much secondary. I think you could say that all faces in sculptures are to some extent masks, so I’m not unusual in that. But I do love to look at how faces are made in sculptures historically and the stylizations that are employed in masks from different cultures. When they are successful, they reflect a truth about the face and its expressions. Often the most stylized or seemingly fantastical representations of the face feel the most realistic. Darth Vader and Spider Man are unbelievably powerful images of a human face, as was David Bowie in the Ziggy Stardust mask. I create faces or heads or masks usually with the idea that they will be part of a bigger sculpture, but sometimes they are so complete or tell such a clear story that they become complete works, and I present them like that.

RRL: How did you develop your working style, your technique, and the materials that you use?

TH: When money was a problem, plaster and clay offered a cheap and fairly easy way to make forms. By the time I had money, I realized that there were endless possibilities in those simple materials. I also wanted to get away from the found-object work that everyone was making. It seemed to be about playing with a very limited series of signs, or worse just about presentation, or worse still decoration. I found plaster and clay to be very versatile and very unforgiving – there was nowhere to hide – and I liked that challenge.

RRL: Can you describe the casting technique?

TH: I make waste-molds on the clays – very old school and simple in one sense. There is also a lot of risk and tremendous physical effort in the process, which is important for the pieces because you have to be focused and sure that you want to go ahead and cast in clay. I also use a process where I drape plaster-soaked hemp over clay and use that directly as a form. I also make a kind of ‘cast’ of a drawing where I pour liquid plaster over a drawing made flat and full size on a board on the floor, then strengthen the back of this plane, wait until it dries, and then lift it. Thus the drawing is cast/printed and can become a physical form as part of a sculpture. RRL: Your work is unusual in that drawings are often embedded in and integral to the sculptures. What is the role of drawing in your work?

TH: Drawing is central to the whole process. I draw every day and consider the drawings as plans or blue-prints for the pieces. Everything begins through that activity. As I explained, many of the sculptures are casts or prints of drawings. I love the idea that a doodle or simple line drawing can become a monumental bronze work, that the intimacy and speed of drawing can still be at the center of a piece. People rarely realize that the drawing on the pieces is printed. They assume that I’ve drawn directly onto the sculptures, which I rarely do.

RRL: Your sculptures often show evidence of their making, such as exposed rebar and visible structural components.

TH: In a very general way, you could say there are two approaches in sculpture to the act of making: one tends toward removing traces of the hand and the physical activity of the artist, and the other emphasizes that activity. Both have a long and great history. I recently saw Michelangelo’s Rondanini Pietà and was stunned by how radically he approached the act of representation and the act of making. That sculpture can lead you straight to Rodin and from there all the way to performance art, Bruce Nauman, and the sculpture of Paul McCarthy. Partly because of my temperament, I need to be very involved in the activity of making, which is probably the Luddite in me. I am fascinated by the actions that an artist takes to make something, and I want them to be an important part of how you see and read the piece. I also like the idea of making the creative act accessible, showing that it is not some super-refined or distant thing, or something that requires huge financing, or some icy virtuosity – showing anybody can make art if they have the will and desire. For me, that is the magic in sculpture.

RRL: For the Whitney Biennial 2010, you created ‘Baby,’ a huge, squatting figure. What inspired that sculpture?

TH: It came from a number of factors. At the time, my wife was very pregnant with our son, Abe. While we were overjoyed about that, the world around us seemed threatening and vulnerable. The huge ‘Station Fire’ was burning very close to our house, and down at the studio in Boyle Heights, there were several gang murders. In one case, the bullets entered the building close to where I was working on the Whit- ney piece. The economy was in free fall, and there was a sense of having to stay strong and somehow hopeful. I was also about to show my first piece in New York City. It was, and still is, a big deal for me that America included me in its biennial, so I wanted to make something as if it were my last-ever work. Then, as I watched my son being born and going through that ancient process of becoming a human, I thought of the Sphinx riddle: What goes on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three legs in the evening? The title Baby just seemed perfect.

Thomas Houseago, ‘Baby’, 2009 © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, Xavier Hufkens and L&M Arts, Los Angeles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

RRL: Your figures have an uncanny ability to look both powerful and vulnerable at the same time, perhaps, in part, because of their fragmented construction.

TH: I am not afraid of trying to give a work a powerful energy. I believe that art can be powerful without being bombastic or macho, and not everything has to end up being ironic. But I am wary of a kind of human social power that dictates while denying doubt and weakness. Often I find that my biggest, most seemingly intimidating works are the most ludicrous and fragile, but I don’t really push that. My experience growing up has made me deeply suspicious of social power structures and the idea of a dominating, impenetrable male power. I’ve always loved the Dylan lyric, ‘Even the president of the United States must sometimes have to stand naked.’

RRL: How would you characterize what you are trying to achieve in your work?

TH: That is an impossible question to answer well. On one level, I am just trying to remind people that you can provide another perspective on how things could look. On another level, selfishly, I am trying to understand what it is to be alive and think and feel, and to explore that in my work, like the question posed by Gauguin, ‘Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?’ But as a sculptor, bottom line, I am trying to put thought and energy into an inert material and give it truth and form, and I believe there is nothing more profound than achieving that. Rachel Rosenfield Lafo is a writer and curator based in Portland, Oregon. She was formerly Director of Curatorial Affairs at the DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum.

Related News

1 / 5