Zhang Enli. The Secret Life of Things

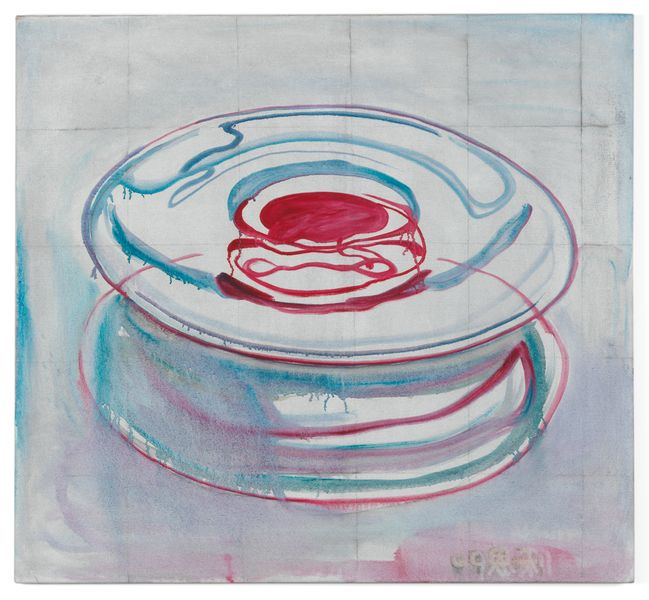

Zhang Enli, ‘Fruit Dish’, 2009 © Zhang Enli. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Barbora Gerny

Zhang Enli. The Secret Life of Things

Zhang Enli has spent the last fifteen years painting portraits of what might generally be conceived as the banal and commonplace objects that occupy quotidian life. Formed by loose, lyrical brushwork in thin washes of heavily diluted oil paint, Zhang’s paintings depict objects including weighty, leather arm chair; a bare, lacquered table with spindly leg; crazy patterned footballs; slender, armless swivel chairs: the inside of a candy-coloured stripy umbrella; tile bathroom walls; and plain cardboard boxes.

What has, perhaps, enabled these standard accoutrements to discharge such magnetism – unobtrusive though it may be – is the artist’s ability to portray them with the rare luster and intimacy for which he has become recognised. The repetitive grid motif of a murky sink becomes an exercise in geometry (Flume, 2006); a light hanging from a ceiling transforms its blackened surroundings with delicate crystal ovals bunched together in a baroque mound (Pendant Lamp, 2006).

Perhaps it is the literal spotlighting employed by the artist – bathing his portraits with a stark, sometimes fluorescent, glow – which operates as a critical component in elevating that which he is showing us. Surprisingly, Zhang only ever uses artificial light when he is painting in his studio, but this is mostly for reasons relating to consistency. “If I were to paint in natural light the light would change throughout the day, affecting my work. Consequently, the colours in the painting would be much more different.”

Zhang Enli, ’Transparent Shelf’, 2013 © Zhang Enli. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Even when transforming a cotton rope into cobalt green loops (Tension 1, 2013) or presenting a rich blue textile (A Carpet, 2011), the artist’s palette always keeps a muted, steady presence which is possibly aided by the employment of electric light. Zhang who grew up in the small town of Jilin in the north of China in the 1970s and now resides in Shanghai, has commented on the universality of his subject matter, referring to both constancy as well as commonality.

“Most people like extraordinary things, but they are not important,” he once said. “The spectacular things might attract you, yet the truths we are really looking for are always hiding behind those common objects.” The homely and unexceptional nature of habitual experience could perhaps, then, be understood as the most significant and reliable indicator of time and history, and the sentience of Zhang’s object portraits – which are so imbued with the artist’s own emotions – creates not reality, but, much more importantly, feeling.

“I deal with reality in order to express something that goes beyond reality.” Meeting with Zhang whilst he was in London for the installation in his exhibition at Hauser & Wirth – the gallery that has represented him since 2007 – I engaged with a modest and low-key character who readily laughed and was warm and good fun. What stood out the most to me about Zhang as an artist was the role that personal expression and emotion play in the formation of his art, as well as his insistence on simplicity when thinking about his work.

“Of course, I am influenced by outside elements,” Zhang has said previously, “but you don’t just take it and use it yourself. You take it and digest it, and then what you create becomes something different.”

Zhang Enli, ‘Six Balls’, 2012 © Zhang Enli. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Stefan Altenberger Photography Zürich

Memory plays an important role in your work. You have said that painting makes us use our eyes in order to instigate our imagination.

I suppose that’s why I choose to paint the outside of objects. I focus on the outside not the inside because I want to raise the viewer’s curiosity about what is inside the box or the container. I want to encourage thoughts about the object and make the viewer pay close attention to how they look at something. So by not including content – the inside of something – I want to remind the viewer to use their imagination, to follow their curiosity. I could paint a hundred apples inside a box but that would be meaningless. However, if you cover the box with a sheet, that becomes more interesting. If you know what is under the cover, you’ll likely forget it. If you don’t know, you’ll probably remember the object you’re looking at more so.

Your own personal memories have formed the basis of what you paint – these everyday objects and domestic interiors.

I do find these things very attractive – chairs, footballs, ashtrays… they are just normal things that can be found everywhere. A lot of these images come from my childhood memories, growing up in Jilin, but they do also relate a lot to my experience of living in Shanghai, where I have been for twenty-five years now. A lot of the objects are within my studio, for example. Or night scenes of the city. I suppose I like taking away certainty from a space or an object – to make people see things go round them with new eyes, and to consider stuff they might usually miss.

Would you say that memory is a theme which has occupied other artists working in China – is it especially culturally pertinent?

Well, for me, memories are not about ‘memory’. As in, the memories I use to form my paintings – of certain objects, say – are used to make us remember certain things. What does this object make you think back to, what associations does it have for you. In life, generally, ‘content’ is really quite meaningless. Humanity is about an experience, about memory itself. The way to understand painting is through memory and feeling. The most important thing is to feel safe. It is not about culture itself, or explicit symbols.

Recently you have developed a series of works called “space painting”, whereby you paint the entirety of a room. You have painted a number of interiors including those in London (the Institute of Contemporary Art), Hong Kong (K11 Art Foundation), Antwerp (Objectif Gallery), Genoa (Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Villa Croce) and Kerala (Kochi-Muziris Biennial). Where did this idea come from?

The idea for these works comes from a curiosity about old paintings found on walls. Actually, I suppose it comes from when I first moved house. I saw a mark on the floor, which had been made by furniture, which had been sitting there. After all the furniture had been moved out, I saw marks of where things used to be. It signaled the passing of time for me. These works also allow me to explore my interest in the relationship between people and painting.

What is your definition of a “space painting”?

There is only one type of painting for me – this is painting. The only difference here is that I have painted onto a wall, rather than a canvas. Using this material makes for a more immersive experience for the viewer – when they enter the space the painting is all around them and underneath them, rather than just one surface in front of them, which is what a painting on a canvas is. Painting on a wall also feels more wild, in a way. A canvas painting is more civilized.

Zhang Enli, ‘A Roll of Wires’, 2012 © Zhang Enli. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Stefan Altenberger Photography Zürich

What is your favourite time of day to paint?

I love to begin drawing in the morning, because the light is better. I guess I consider both the weather and also how I’m doing physically, and when both of these are in good situations, I paint.

What is it like to be an artist in Shanghai now?

There is a great change in the city. The young artists and young galleries are more active, and increasingly more people pay attention to art. I love Shanghai, life is very convenient. But for a lot of artists the cost of living is still pretty high. Many of the younger artists will have another job as well, to cover their families’ expenses, and so on.

The well-known Moganshan Road art district in Shanghai, where your studio is based, has seen a large amount of gentrification over the last few years.

This area used to be full of old textile factories, then about ten or eleven years ago the government decided to regenerate it into an art district. So now there are lots of artist studios and galleries based there. It has a very different atmosphere now, which I think is good.

Your work is regularly shown internationally. Do you enjoy travelling to other cities?

I do. I really like the big city – so many people, so many cars. I would say that places I enjoy in particular are London and New York. And of course, Shanghai.

When did you feel you first received recognition as an artist?

Probably when I showed at Art Basel (the annual art fair in Basel, Switzerland) in 2002. It was the first time my work had been shown in that kind of international setting. It was especially significant for a Chinese artist to be presented there. Art Basel opened the door to Chinese artists at this time. People will perhaps think this is strange because normally artists become well known after they have had an academic exhibition at a museum or gallery. But it was after Basel that more people became interested in Chinese artists, and they definitely focused more on me after I exhibited my paintings there.

So Art Basel was a breakthrough of sorts for Chinese artists. Was it the case that Chinese artists were not having the opportunity to exhibit their work outside China prior to this?

Maybe before this time a lot of Chinese artists were already starting to show in the West, but these were group shows where ‘Chinese’ was essentially the theme. Those exhibitions were not focused necessarily on the artist’s work. After Basel in 2002 I feel as though the focus definitely turned to the actual work itself, and the artist as an individual, rather than trying to group artists around Chinese culture or politics, for instance.

What was your first impression of Europe?

Basel wasn’t actually my first time in Europe. In 1995 I went to Sweden. I was shown in a group exhibition called ‘Change China Contemporary Art’ at Konsthallen Gotaplatsen in Gothenburg. I was very excited about it. As I mentioned, it wasn’t really common, especially so early on in the mid-1990s, for Chinese artists to show in Europe.

Installation view, ‘Zhang Enli. Landscape’, Museo d’Arte contemporanea di Villa Croce, Genova, Italy, 2013. Photo: Nuvola Ravera

Your first solo exhibition in Europe was nearly ten years ago at W&B House/Buero Friedrich in Berlin.

That’s right. And in 2006 I participated in a group exhibition in Udine, Italy, called ‘Infinite Painting and Global Realism’. It was curated by Francesco Bonami, a very influential curator. That exhibition was important for me, it was really the beginning. I remember visiting the gallery, and in the entrance hall I saw my works displayed there, and it was just thrilling. In front of my work there was a work by the painter Marlene Dumas. We were being shown together! That was just such an important moment for me.

Did you feel that same excitement when you were included at Art Basel?

Yes, and that was another learning experience. When I went to Basel I got a chance to look at so many Western artists, and that was very good for me. There were so many galleries at the art fair which I got to visit. In China it would have been impossible to see so much. Normally I would have seen such works in magazines and so on. So to see them in person…. It all made a very big impression on me. I remember seeing paintings by Martin Kippenberger, they were so powerful. Seeing everything first-hand for the first time, that was really something.

Which other artists have interested you?

I enjoy the mural paintings and the Zenith paintings in the churches of Italy. Tintoretto’s paintings – I think they look like the clouds in the sky in the north of Italy. I have always admired Francis Bacon. His works have masculine lines, they are really strong paintings. At art school I was very interested in Edvard Munch. I’m still really taken aback even now when I see his works. I always like visiting Tate Modern, and the Dia Art Foundation in New York is interesting.

What emotion do you want people to feel when they look at your paintings?

Surprise. I think I actually just want my work to make people stop, and look. You cannot expect too much else, especially nowadays when people are bombarded with information of all types. If people can give my paintings a bit of time, and let themselves look for just that little bit longer, I’ll be happy.

Installation view, ‘Zhang Enli’, Hauser & Wirth London, 2010. Photo: AJ Heath

Related News

1 / 5