Paul McCarthy

16 October - 20 December 2003

London

About the Artist

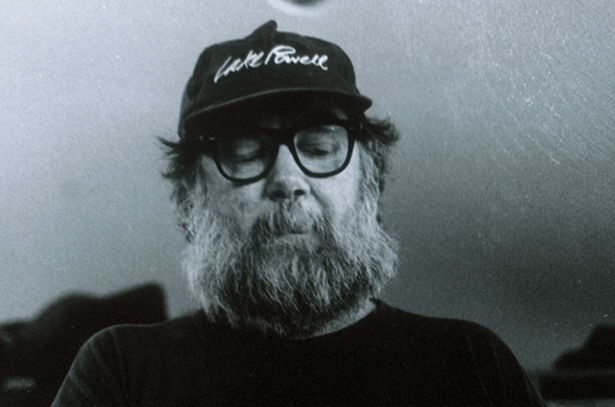

PAUL McCARTHY

Paul McCarthy is widely considered to be one of the most influential and groundbreaking contemporary American artists. Born in 1945, and raised in Salt Lake City, Utah, he first established a multi-faceted artistic practice, which sought to break the limitations of painting by using unorthodox materials such as bodily fluids and food. He has since become known for visceral, often hauntingly humorous work in a variety of mediums—from performance, photography, film and video, to sculpture, drawing and painting.

During the 1990s, he extended his practice into installations and stand-alone sculptural figures, utilizing a range of materials such as fiberglass, silicone, animatronics and inflatable vinyl. Playing on popular illusions and cultural myths, fantasy and reality collide in a delirious yet poignant exploration of the subconscious, in works that simultaneously challenge the viewer’s phenomenological expectations.

Whether absent or present, the human figure has been a constant in his work, either through the artist‘s own performances or the array of characters he creates to mix high and low culture, and provoke an analysis of our fundamental beliefs. These playfully oversized characters and objects critique the worlds from which they are drawn: Hollywood, politics, philosophy, science, art, literature, and television. McCarthy’s work, thus, locates the traumas lurking behind the stage set of the American Dream and identifies their counterparts in the art historical canon.

McCarthy earned a BFA in painting from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1969, and an MFA in multimedia, film and art from USC in 1973. For 18 years, he taught performance, video, installation, and art history in the New Genres Department at UCLA, where he influenced future generations of west coast artists and he has exhibited extensively worldwide. McCarthy’s work comprises collaborations with artist-friends such as Mike Kelley and Jason Rhoades, as well as his son Damon McCarthy.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 12