Diary

What the Body Knows

Artists explore aura through movement, matter and memory at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong

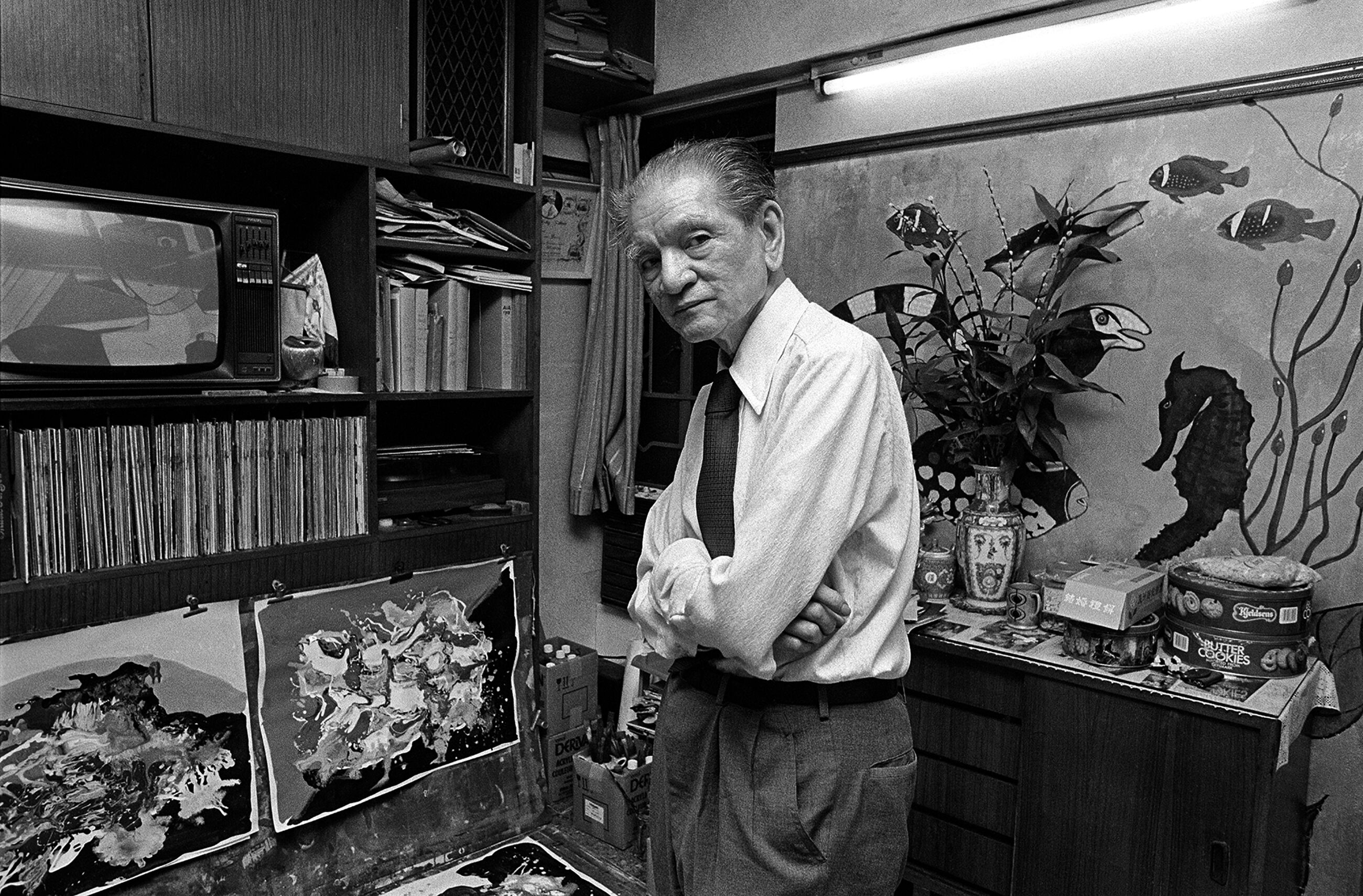

Luis Chan, Man with Saw-teeth, 1969 © Luis Trust. Courtesy of Hanart TZ Gallery

This summer in Hong Kong, “Aura Within” brings together nine contemporary artists in a meditation on the body as both medium and witness—an expressive site where history, trauma and memory take form. Drawing on Eastern philosophy’s notion of the unity of form and spirit, and Walter Benjamin’s concept of “aura”—that elusive quality anchored in time, place and material experience—curator Anqi Li poses the question: Can the body itself become a vessel for aura? In a world shaped by algorithmic governance, digital estrangement, and post-pandemic disembodiment, the exhibition asks how presence might be reclaimed and explores how an artwork holds its aura.

For Ursula, Anqi Li speaks with artists Nicole Coson, Shota Nakamura, Peng Ke, and Haneyl Choi to understand how personal history, process and form intersect in their work. Gallerist, writer and curator Johnson Chang reflects on the work of the late Luis Chan, whose dreamlike ink worlds captured the psyche of postwar Hong Kong. Through physical imprint, associative memory, urban poetics and sculptural introspection, the distinct visual languages of these artists do not merely depict the body—they emerge from it.

Nicole Coson in her studio. Photo by Nora Nord

Nicole Coson

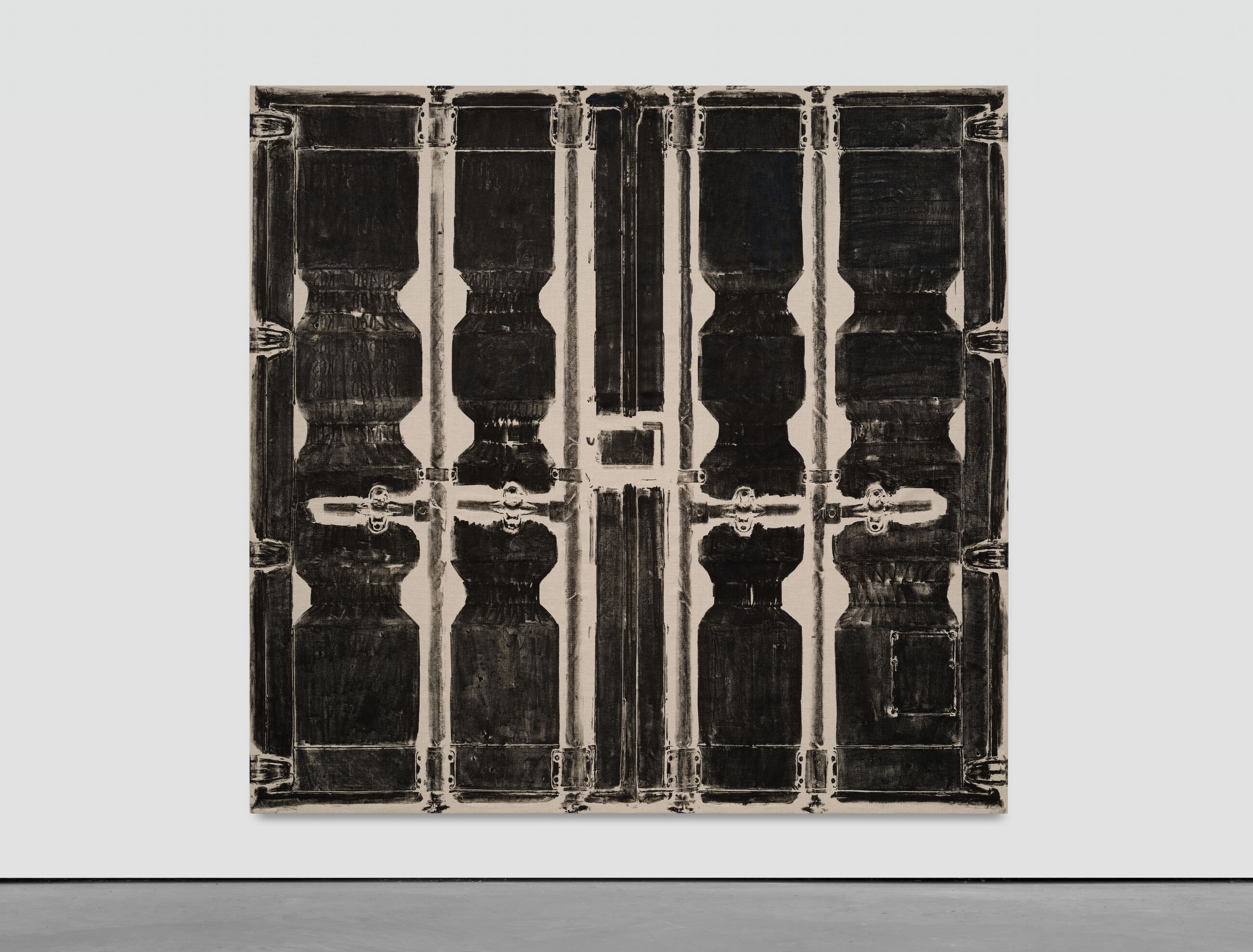

Anqi Li: The “aura” of an artwork is defined as its unique material history in time and space. Your new works use bodily printmaking—a performative, physical act—to translate the symbolic meaning of shipping container doors into brushstrokes on canvas, creating an aura for your work. What drew you to shipping containers as a symbolic subject, and how did your bodily experience shape this translation?

Nicole Coson: I see shipping containers as a kind of blood cell, circulating through the capillaries of the global trade network. They are symbols not only of the distribution of goods but of cultural exchange and migratory trajectories; they are carriers of histories, moving across oceans, harbors and borders.

By treating the container like a giant woodcut, I attempt to capture its essence beyond its steel shell. I remove it from circulation, dislocate it from its original purpose and invite the viewer to look more closely at the vessel in suspended animation. Its standardized, mass-produced form bears the individual scars of its journeys: displaying notches, stickers and dents. These blend with marks made by my own body.

Nicole Coson, Double Doors I, 2025

To capture the contours of the doors, I work directly on top of them. Weighing a combined 150 kilograms, the steel is propped inches off the ground in my studio. By crawling, dragging ink across canvas and repeatedly scratching and pressing to create an imprint, this physical process becomes part of the image. My body’s movement, marks made by my knees, elbows and hands, merge with the container’s surface. In this way, the canvas and ink act as mediators between the human and the industrial. The final work becomes a shared imprint: a collision between a body in motion and an object shaped by movement, both revealing and withholding stories yet to be told.

Portrait of Shota Nakamura. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Los Angeles. Photo: Jordan Weitzman

Shota Nakamura

Anqi Li: Your paintings evoke fragments of a nonlinear film—collaged from archives, personal memory, art history, classic cinema and sometimes pop culture. This creates a haunting familiarity, inviting viewers into dreamlike spaces built from real-world traces and imagination. How does this montage-like process inform your new works in “Aura Within”?

Shota Nakamura: My new work untitled (garden) started with an iPhone photo I took of a film I saw years ago—though I can’t recall the title. There was a scene with students in the Berlin Botanic Garden, studying and describing flowers. That image became the seed of the painting.

Shota Nakamura, Untitled (garden), 2025 © Shota Nakamura. Courtesy the artist and

C L E A R I N G New York / Los Angeles

“Image-making is inherently anachronistic. It links deeply personal, trans-temporal points across a vast visual pool.”—Shota Nakamura

What drew me in was the relationship between the body and its surroundings. The act of placing oneself in a setting and entering a state of focused observation—this bodily immersion—felt profound. The image reminded me of Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1984-86), especially his preparatory studies. I even visited the Berlin garden as part of my research.

Much of my work emerges from memory, observation and image research. That research includes not just paintings but film stills, photography, even smartphone shots. The process often starts with a moment of encounter—an image that triggers a chain of associations.

To me, image-making is inherently anachronistic. It links deeply personal, trans-temporal points across a vast visual pool. The “familiarity” you mention may come from a kind of déjà vu. I recontextualize pictorial languages from art history—color theory, mark-making, subject matter—while drawing in more marginal reference points. That’s the foundation of my approach to painting in a contemporary context.

Peng Ke. Courtesy the artist, Chanel Nexus Hall Tokyo, and Make Room

Peng Ke

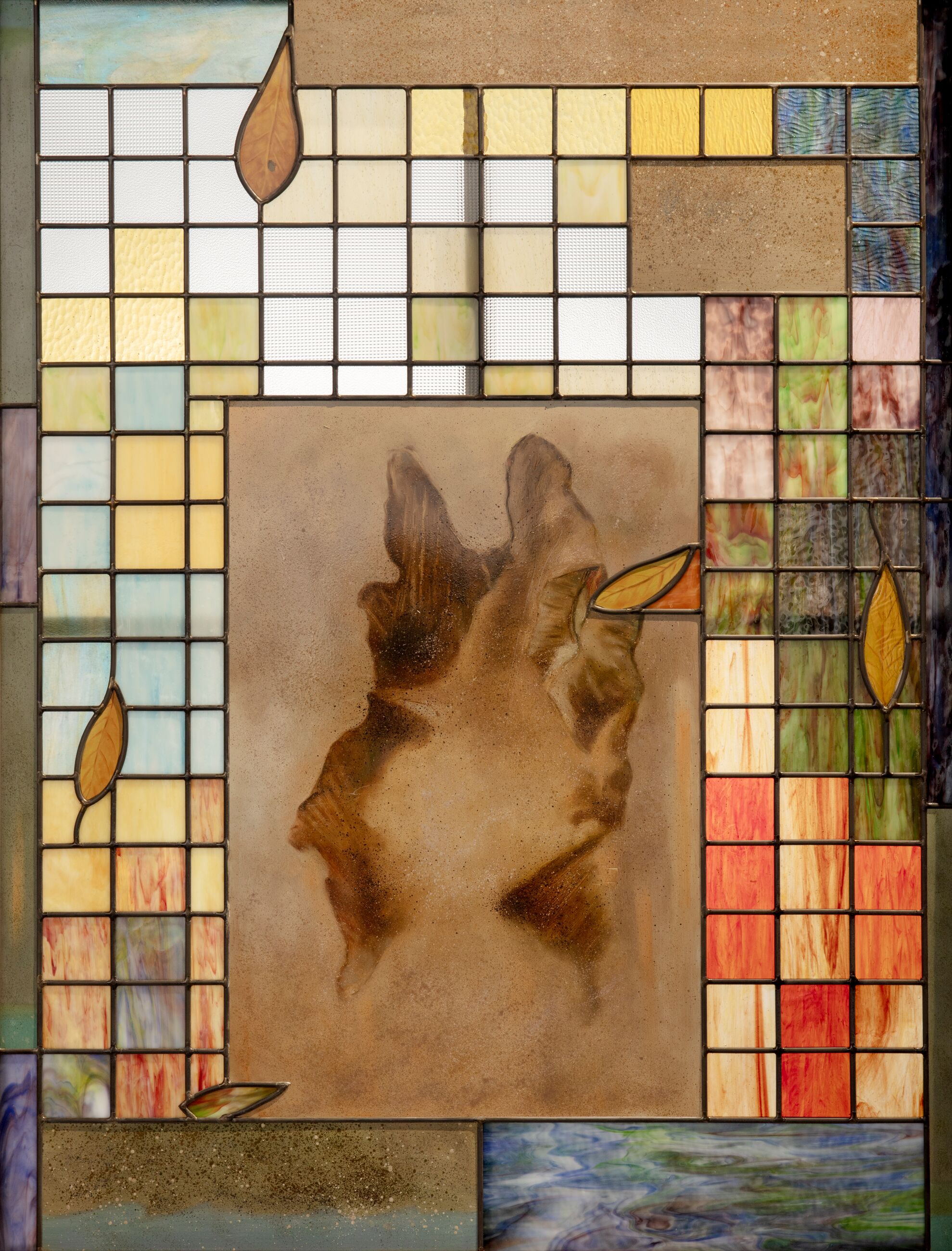

Anqi Li: You’ve described glass as an extension of your camera lens, admiring its qualities: enduring yet fragile, historical yet modern. Traditionally, stained glass creates a sacred halo, and in your work, it abstracts photographed subjects into luminous glass panels that sanctify often ordinary urban details. What is the story behind the work on view in “Aura Within,” and what does transforming photography’s materiality into stained glass mean to you?

Peng Ke: I would like to think of my work as a celebration of the most mundane yet sublime moments in life. At least, that is what I have always tried to construct in these pieces—a discreet homage to the subtle beauty embedded in our daily experiences.

Peng Ke, Begin Again, 2024 © Peng Ke. Courtesy the artist, Chanel Nexus Hall Tokyo, and Make Room

My work is tied to the world I grew up in—densely populated cities where space and time are constantly negotiated among countless individuals. In these environments, we’re exposed to the push and pull of shared existence: crowded streets, overlapping conversations, fleeting glances and layered architecture. Amid all this, it’s easy to lose track of oneself. However, there are also moments of unexpected clarity—pauses that reveal what life is really about and how it continues with quiet persistence.

I try to capture those moments to expand the viewer’s emotional capacity, helping them see the familiar from a slightly shifted angle. The materials I choose—realistic imagery, stained glass panels, oil on panel and stock fabric—reflect the layering of experience and a delicate balance between chaos and harmony. Through this process, I hope to create a contemplative space where viewers rest their mind, reconnect with themselves and are reminded of the undeniable joy of being alive.

Haneyl Choi. Photo: Joe Sung Hyun

Haneyl Choi

Anqi Li: Landscape of Abuse (2025) imagines the body’s inner world as, in your words, “free,” “mysterious” and “erotic”—untouchable by external proof. Trauma, both physical and mental, becomes a philosophical lens. You cite Sara Ahmed’s idea of pain as “opening up to the other.” How does this and other works in your practice express that state of being?

Haneyl Choi: Sara Ahmed always offers a clue to difficult questions. She writes, “The fact that we cannot live in another person’s body generates the desire to know ‘what it is like’ to feel another’s pain.” That speaks to the solitary nature of suffering.

Haneyl Choi, Landscape of Abuse, 2025 © Haneyl Choi. Courtesy the artist and P21. Photo: Sang-tae Kim

This work unfolds memories, nightmares, secrets etched into the body, turning them into a kind of landscape—an offering of that solitude. Of course, this “map” of the body is a private sensation, one that can never be fully shared. And yet, when this work meets the viewer, I hope the impossibility of full transmission stirs a desire to know what someone else’s pain feels like.

In other words, I want the people I love to feel my pain with me—to acknowledge it. Presenting a sensory corridor marked by trauma, layering sculpture with shame and embarrassment, is my way of expressing a quiet longing for recognition—for someone to notice pain that is not theirs.

Luis Chan in his Wan Chai home studio. Photo: Cheung Ching Ming, 1982

Luis Chan

Anqi Li: Luis Chan’s monotype-inspired abstractions—born from ink’s spontaneity and Hong Kong’s everchanging society—unfold into kaleidoscopic worlds of whimsical figures and landscapes. Having worked closely with Chan during his late career, how did his depictions of embodied forms––whether contorted or fantastical––mirror Hong Kong’s physical and psychological experience of perpetual transformation?

Johnson Chang: In the mid-1960s, when Luis Chan crossed the threshold of abstract monotype prints to enter his private fantasy world, Hong Kong was experiencing yet another economic boom. Since 1949, after the People’s Republic of China won the civil war, the colonial government had dealt with several such “booms,” beginning with the massive inflow of Chinese refugees around 1950—bringing both labor and skilled knowledge.

During these postwar decades, Hong Kong was sheltered from the global conflicts of the Cold War and enjoyed rapid economic growth. But beneath the glitter of success, the city’s psyche harbored multiple anxieties. Some stemmed from fast-paced local social change; others from regional instability, especially among immigrants with close ties to the mainland. Although Mao’s radical politics stopped at the border, its psychological impact was felt across it.

Hong Kong’s role as a hub for international commerce and diplomacy added a layer of quiet tension. There was an awareness that China’s radical politics had roots in the legacy of Western imperialism—the same West that was now profiting from Hong Kong’s boom. For many, especially those with origins in China, prosperity came with an unspoken cost. Perhaps because these benefits went largely unacknowledged, the city’s Cold War prosperity demanded a kind of psychological compensation. For Chan’s generation—who had lived through the 1911 Republican revolution, the Japanese occupation and now the Cold War’s shadow over China—this may have taken the form of survivor’s guilt.

Luis Chan, Untitled (Legend of Goddesses of the Sea), 1968 © Luis Trust. Courtesy of Hanart TZ Gallery

“Luis Chan was a rare soul who allowed the psyche of Hong Kong to speak through his work.”—Johnson Chang

I was always curious why Luis Chan couldn’t explain the strange, dreamlike images of his own creation. When asked, he would answer with humor or playful deflection. I believe these were honest responses. He may have been as confounded by his own inner world as his viewers were.

By the mid-1960s, geopolitical tension was again pressing in. Mao’s Cultural Revolution had begun in 1966. The Vietnam War was escalating, bringing American soldiers to Hong Kong on rest and recreation. These distant conflicts arrived in the city in a peculiar mix of tabloid clamor and riotous nightlife. For Chan, it arrived quite literally at his doorstep: he lived in the Wanchai district, where soldiers gathered, from the 1960s until his passing in 1995. One door down from his apartment was the topless Mermaid Bar.

It was a time of swift and disorienting change. Life moved to the beat of the stock market. Chan stayed close to that pulse. As a mature and sociable man, he absorbed in good humor what his mind could not process, and allowed his soul to make peace with contradictions through art. His ability to channel confusion into visual form gave structure to chaos. One might go so far as to say Luis Chan was a rare soul who allowed the psyche of Hong Kong to speak through his art.

–

Featuring works by Luis Chan, Haneyl Choi, Nicole Coson, Bharti Kher, Tetsumi Kudo, Shota Nakamura, Peng Ke, Yeh Shih-Chiang and Zhang Enli, “Aura Within” is on view at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong from July 10 – August 30, 2025.

Anqi Li is an independent curator and scholar based in Hong Kong. Currently a PhD candidate at the University of Hong Kong, she focuses on the cultural politics of contemporary art institutions. She was formerly the Curator of Education and Public Programs at Para Site and has worked at Harvard Art Museums, Hammer Museum and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Recent projects include Supper Club (2024), "Liminality" (West Bund Museum, 2023), "Lost in Translation" (Galerie du Monde, 2023), and "Curtain" (Para Site, 2021). Her writings have been published in the Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, Artforum and ArtAsiaPacific, among others. She holds an EdM from Harvard University and a BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute.