Essays

This is Our Childhood

Jonathan Cott on the spirit world of the Lascaux cave

From The Birth of Art by Georges Bataille (NY: Skira, 1955). Courtesy Skira, New York. Photo: Hans Hinz

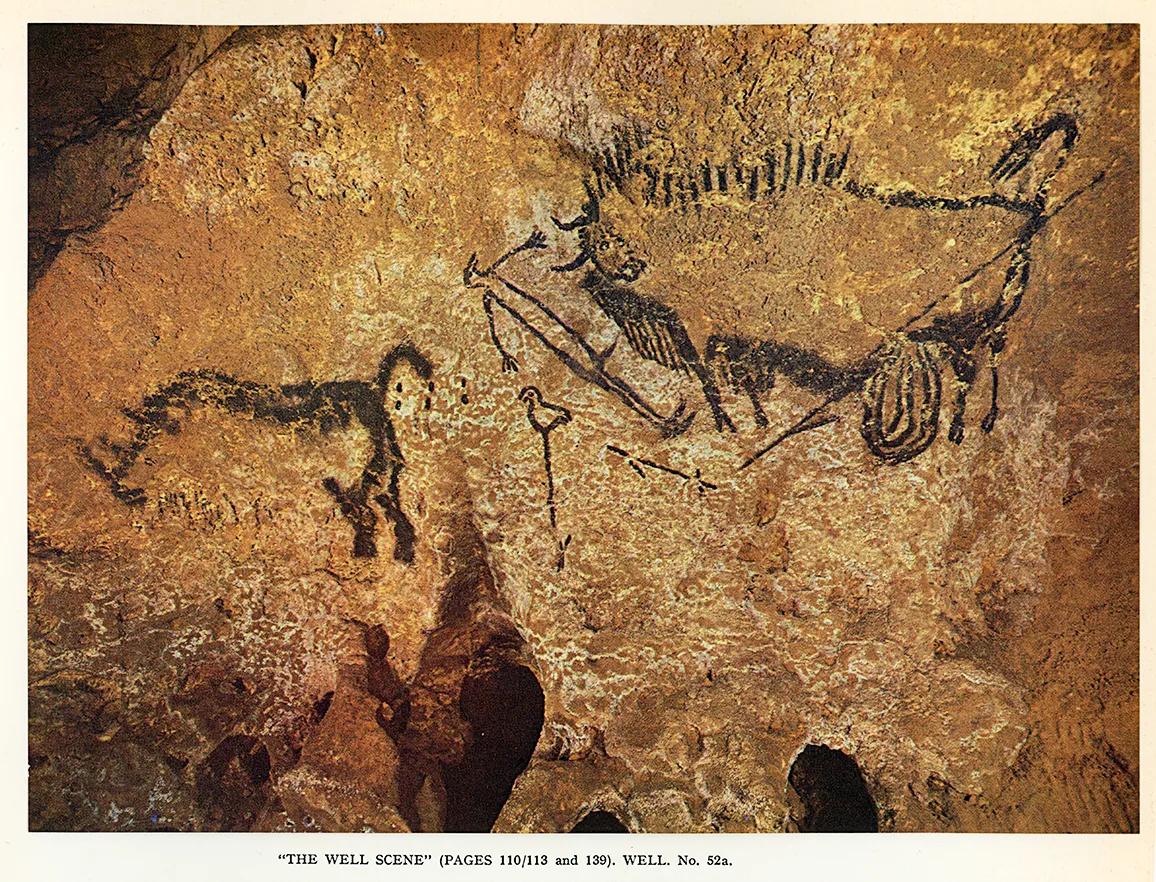

In the heart of the Lascaux cave, located near the village of Montignac in the department of the Dordogne in southwestern France, is a sanctuary called the Shaft, whose walls are adorned with one of the few narrative scenes in all of Paleolithic art.

This approximately 17,000-year-old painting—in plain earth pigments of red and yellow ochres and black manganese and charcoal—depicts a stick-figured, bird-masked man with outflung arms, bird’s-foot-like hands and an erect phallus hovering above a bird poised on an upright staff, a barbed stick beside his feet. The man is falling backward, or is in the throes of an ecstatic trance, or is lying supine, dead, beside an eviscerated bison, a spear piercing its flank, its entrails streaming out, hair raised, tail flipped forward lashing the air, while a rhinoceros, tail turned backward and six black dots issuing from its anus, nonchalantly strolls away. The Bird Man is the only human figure portrayed in the cave, and one of the few in all of prehistoric Western cave art, and the bird on the stick is the only bird depicted in the cave.

The earliest explanation of cave paintings was that they were simply decorations. Later scholars suggested that the paintings were magical, religious symbols, or had their origins in the idea of clan-totemism. But why were many of the painted animals shown to be wounded? Perhaps, it was surmised, the images functioned as a kind of “sympathetic magic,” the representation of an animal being a way of dominating it. But as the French paleontologist Jean Clottes, co-author of the pathbreaking book The Shamans of Prehistory: Trance and Magic in the Painted Caves, said, “Imagine those people coming this far inside the earth with their flickering grease lamps and torches of pine wood that didn’t cast much light. The place is wet and dank. It’s dangerous. They walked more than a mile. They had to have a very strong reason for coming here. Perhaps they came in order to get as close to the spirits as possible. The cave paintings do not represent real animals that are hunted for food in an actual landscape; rather they are visions drawn from the subterranean world of spirits because of their supernatural powers and ability to help the shamans.”

According to historian of religion Mircea Eliade, shamans are men or women who “journey” in an altered state of consciousness to upper and lower worlds; shamanism is a system of beliefs that includes healing techniques, rituals designed to affect events and the elements, prophecy, witchcraft and the "possibility of communicating with spirits; and in the shamanic world, boundaries between the animal and the human are permeable and constantly blurring.

To psychologist Stanley Krippner, shamans were “the world’s first diagnosticians, first psychotherapists, first religious functionaries, first magicians, first performing artists and first storytellers,” and trances, which can be produced in various ways, are the means used by shamans to take on their powers. To Joseph Campbell, among others, the figure of the Bird Man of Lascaux was not that of a hunter slain by an animal but, rather, a representation of a prehistoric shaman with his ceremonial bird-headed shaman stick on a trance-induced journey to other worlds.

But couldn’t one also see this scene as the dream of the Bird Man himself?

From The Birth of Art by Georges Bataille (NY: Skira, 1955). Courtesy Skira, New York. Photo: Hans Hinz

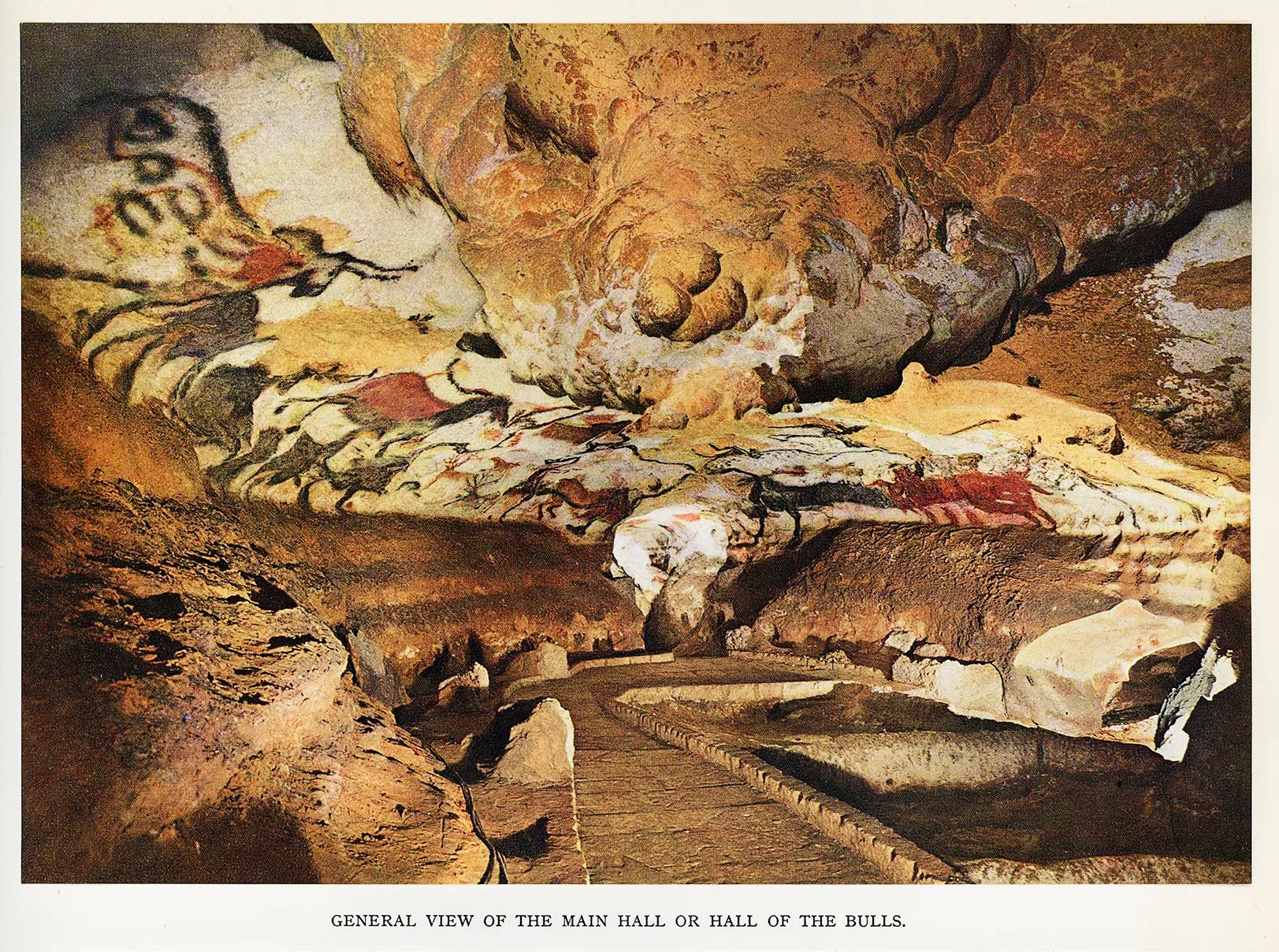

Over the years, this painting has been interpreted in a myriad of ways. Dr. Michael Rappenglueck of the University of Munich has even suggested that the Shaft painting is a sky map on which the eyes of the bison, bird man and the bird on his shaman staff represent the three prominent stars Vega, Deneb and Altair, known as the Summer Triangle. He also posited that the cave’s spectacular Hall of Bulls, which has been called “the Sistine Chapel of Prehistory,” with its procession of bulls, equines, aurochs, ibexes and a mysterious unicorn-like creature—a spectacle Georges Bataille referred to as a “dance of the mind”—is a star map of the Pleiades and Taurus. “It’s a map of the prehistoric cosmos,” Rappenglueck proposed. “It was their sky, full of animals and spirit guides.” And although this story is probably apocryphal, one that might be thought of as what Martin Buber called “legendary reality,” Picasso, having visited the cave after World War II, reportedly said to his terrestrial guide, “In 15,000 years, we have invented nothing.”

The cave was discovered one late September afternoon in 1940 when four teenage boys climbed up the side of a hill searching for buried treasure and Marcel Ravidat’s dog, Robot, chasing a rabbit, stumbled into a hole in a thicket. The boys went home, but four days later, Marcel made a makeshift lamp using a cotton wick from an automobile’s oil pump and returned to the site with his three friends. They widened the hole with sticks and Marcel’s large homemade knife, and Marcel squeezed through a small vertical shaft headfirst, landing safely on the floor of the cave. He urged his three friends to join him, and they descended, making their way gingerly through a passageway that turned into a narrow corridor. When Marcel raised his lamp, his friend Jacques Marsal looked up, shouted out to his companions to lift up their eyes, and for the first time in some 17,000 years human beings saw in the faint, almost quivering, light, the Great Black Bull, the Galloping Horse and the Falling Cow in what is now known as the Axial Gallery.

They returned once again the following day, bearing several other lamps and some ropes and, again, it was Marcel who took the lead. After they all slid down, they discovered another hallway which led to the edge of a hole. The other boys held the rope, and after Marcel descended into the fathomless depths, he shouted up to his friends to say he had landed safely. Walking through a short passage and raising his lamp above his head, he found himself facing a painting that seemed to show the figure of a bird-headed man, lying on his back, with a speared bison hovering over him.

I remember becoming transfixed by the sight of ancient handprints … and of ancient footprints, heel marks of barefoot children … deeply imprinted in the mud and preserved in the hard surfaces of frozen time. Noticing the wrinkled patterns of those small feet, I thought: “This is my childhood.” And then: “This is our childhood—the childhood of the human race.”

It might seem surprising that it is children who have made momentous discoveries in prehistoric caves. In 1879, the archeologist Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, accompanied by his eight-year-old daughter Maria, was exploring the cave of Altamira in Santander, Spain. Absorbed in the laborious process of sifting through the fint-filled clay layers on the floor of the Hall of the Bison, he failed to notice, unlike his inquisitive daughter, that there were a large number of animals painted on the ceiling. “Look, Daddy, bulls!” was what Maria supposedly exclaimed to her incredulous father who, on his own, would never have discovered the haunting assembly of sixteen bison—the models, in part, for Picasso’s Guernica—rendered so magnificently in red ochre and black manganese some 15,000 years ago. As Italian writer Giacomo Leopardi once said: “Children see everything in nothing, adults nothing in everything.”

On July 14, 1948, the Lascaux cave complex was opened to the public, but in 1963 it was closed down because the contamination brought in on visitors’ shoes and the condensation caused by thousands of tourists was affecting the paintings, allowing algae, lichens and crystals to grow on the walls and speed up the process of calcite deposits. However, the demand to visit the cave was so great that in the early 1970s, painters, sculptors and their assistants, working with sketchbook drawings and three-dimensional computer maps, constructed a lifelike recreation of the original two halls—the stupendous frieze in the Hall of Bulls and the smaller Axial Gallery.

In 2016, another replica of the cave reconstituted the original one almost in its entirety. Called Lascaux IV, it was developed by means of the most advanced 3D-printing "techniques, laser imaging and digital photography technology. Painted and engraved murals and drawings are reproduced to the millimeter; sounds are muffled and lights flicker just as the animal-fat lamps of Paleolithic times did. (What was called Lascaux III was not a replica but rather a traveling exhibition, created in 2010, with five fully movable facsimiles that have been shown in thirteen countries.)

The outer shell of the replica of the cave, Lascaux II, during construction in the 1970s. © Ministère de la Culture/ Centre National de la Préhistoire/Norbert Aujoulat

As I listened to an eerie underworld silence punctuated by the dripping pings of water, I had the uncanny sensation that the animals pictured on the cave walls . . . were actually moving.

Lascaux II is not a real cave, and Lascaux IV is still a facsimile. I never had the opportunity to visit the original Lascaux cave, but I wanted to enter and experience an original prehistoric one, so in 1987, I visited the even older cave of Pech Merle in the Lot Valley of southwestern France—not far from the Dordogne—most of whose paintings date from 16,000 to 29,000 B.C. The cave was discovered in 1922 and is still open to the public. I was led down into the depths by the French film director Louis Malle and his then-seven-year-old daughter, who boldly led the way. Noticing that I was edging myself extremely slowly and anxiously down the narrow stairway, whose view of the cavern below was giving me a sudden and severe case of claustrophobia, she blurted out: “If I can do this, so can you!” Louis warned me that I shouldn’t convey any sense of anxiety to his daughter, and said: “You’re going down!”

I will always be grateful to him and his daughter for shaming me into entering, flashlight in hand, a pale ivory sanctuary where, half in trance, I saw white stalactites hanging from the ceilings and golden stalagmites rising from the ground. As I listened to an eerie underworld silence punctuated by the dripping pings of water, I had the uncanny sensation that the animals pictured on the cave walls—floating deer, prancing horses, retreating bison, charging bulls—were actually moving and shimmering in the flickering, shadowy light.

That day at Pech Merle, I remember becoming transfixed by the sight of ancient handprints—originally stamped or airbrushed, using the mouth to blow pigment, on the walls—and of ancient footprints, heel marks of barefoot children, "probably not much older than my friend’s daughter, deeply imprinted in the mud and preserved in the hard surfaces of frozen time. Noticing the wrinkled patterns of those small feet, I thought: “This is my childhood.” And then: “This is our childhood—the childhood of the human race.”

In his fascinating book The Nature of the Paleolithic the zoologist and paleobiologist R. Dale Guthrie proposes that some of the graffiti adorning cave walls might have been created by paleoadolescents. “I am not concluding,” he explains, “that all Paleolithic art is children’s art, only that works by young people constitute both a disproportionate and largely unrecognized fraction of preserved Paleolithic art.”

Entering an Upper Paleolithic cave today, we rediscover the childhood of our dreams, and these dreams begin in the underworld of the psyche. As Joseph Campbell told Bill Moyers: “Whatever the inward darkness may have been to which the shamans of those caves descended in their trances, the same must lie within ourselves, nightly visited in sleep,” and he added: “The caves are dangerous and absolutely dark. And the pictures on the rocky walls are never at the entrances but begin where the light of day is lost and unfold, then, deep within. The painted animals, living there forever in that darkness beyond the tick of time, are the germinal, deathless herds of the cosmic night, from which zone those on earth—which appear and disappear in continuous renewal—proceed, and back to which they return.” As Jean Clottes has suggested: “I think that prehistoric people came down to the caves to get into a different world, the spirit world. Perhaps the wall of the cave was a veil between themselves and another reality.” But as Hans Peter Duerr observed in his book Dreamtime: Concerning the Boundaries between Wilderness and Civilization: “[There] is not the experience of another reality, but rather the experience of another part of the reality.”

–

Jonathan Cott is the author and editor of more than forty books, including The Search for Omm Sety and Wandering Ghost: The Odyssey of Lafcadio Hearn. His most recent book is Let Me Take You Down: Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields Forever.