Conversations

The Best Tailor Makes the Fewest Cuts

An oral history of David Hammons’s 2019 exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Downtown Los Angeles

Compiled by Randy Kennedy

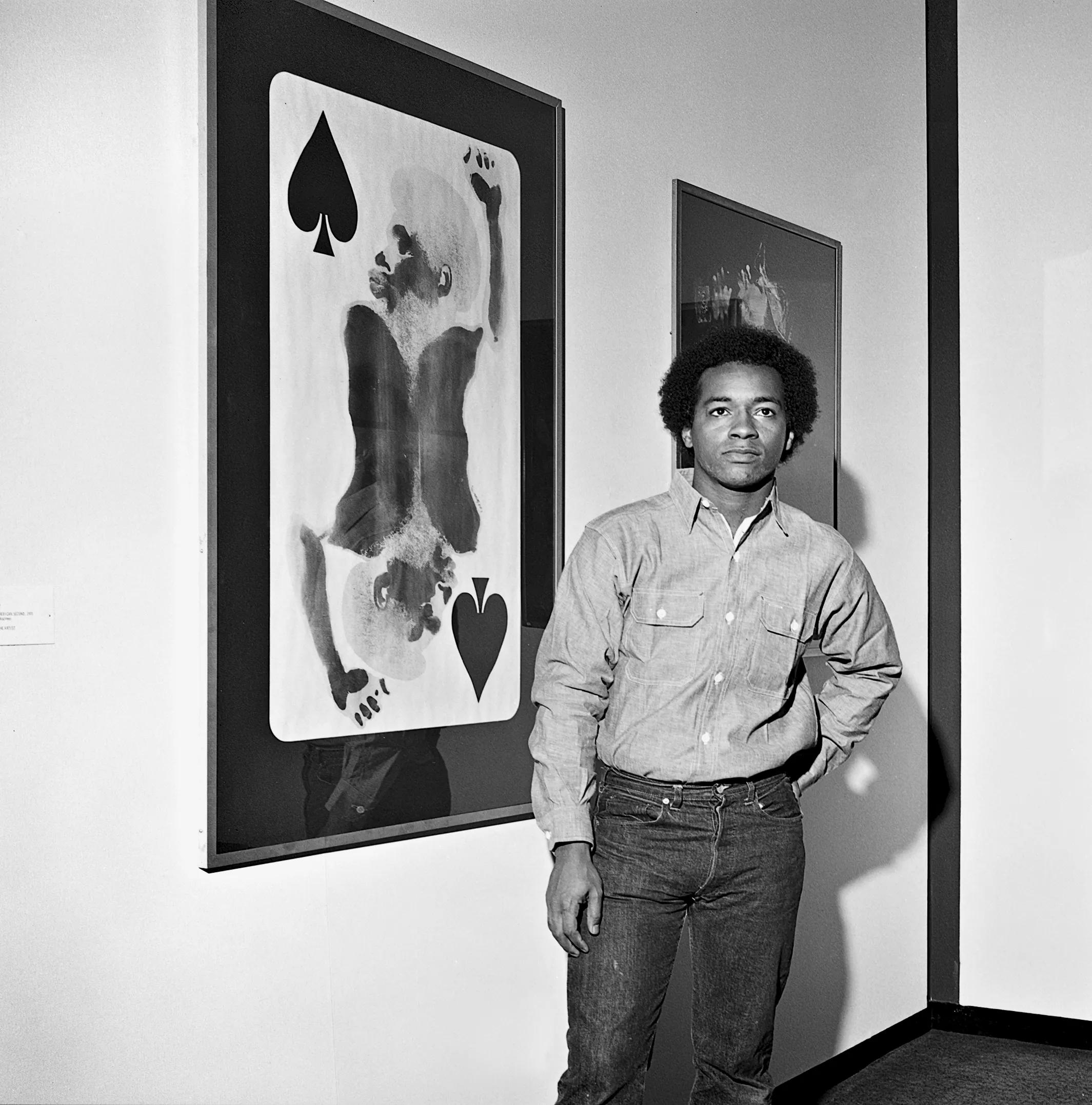

Hammons with Untitled (Basketball Drawing). Photo: Tamar Nahmias

More than any other American artist of his generation, David Hammons has lived and worked in a word-of-mouth tradition—a Homeric, hermetic method of information exchange that tends to confound at least as much as it conveys. Even his most famous work, the 1983 performance that has come to be called Bliz-aard Ball Sale—in which he peddled various-sized snowballs on a blanket in Cooper Square—remains shrouded in hearsay. When did it occur? Probably Sunday, February 13, but no one to this day, besides maybe Hammons himself, can say for sure. Did it in fact happen more than once? How were the snowballs made? How were they priced? The answer depends entirely on the teller and sometimes shifts depending on the time of the telling.

On the occasion of a re-staging of David Hammons’s watershed 2002 exhibition “Concerto in Black and Blue,” on view at Hauser & Wirth Downtown Los Angeles from February 15 through May 25, 2025, Ursula magazine presents a special section on the artist, including a new essay by Linda Goode Bryant, a poem by Ben Okri and the following oral history. The reader should, as the curator Elena Filipovic once wrote of Hammons, proceed with circumspection: “Some of what you read here might, then, be apocryphal.”

Stacen Berg (partner and executive director, Hauser & Wirth): The origins of the show were all fairly mysterious. At some point in 2018, Marc Payot had me hold a slot for an upcoming show but didn’t tell me what it was going to be, which is very unusual. Finally, he told me that he was working on a Hammons idea. It all felt very tentative at that point. We had gotten David to agree, but first he had to come see the gallery. I knew it could all fall apart in a second.

Marc Payot (president, Hauser & Wirth): I remember becoming aware of David’s work in the ‘90s and knowing about his great piece Bliz-aard Ball Sale, in which he sold snowballs on the street near Cooper Union in Manhattan. At the time, I thought of him more as a performer than as a sculptor, though, of course, today I’d describe Bliz-aard Ball Sale as both sculpture and performance. In the early 2000s, Iwan [Wirth, co-founder and president, Hauser & Wirth] and I started having discussions with David that began with the help of Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn [founder, Salon 94], who was working very actively with him, and Lois Plehn, who serves as David’s agent. Quite soon, he decided to do a show with us in Zurich, an installation of cardboard boxes filled with scavenged clothes and stacked on wooden pallets called Made in the Republic of Harlem. There were labels printed on the boxes that said, “Made in the Republic of Harlem,” giving them a Warhol-like feel, which was interesting. In an adjoining gallery he showed Hidden from View, wooden museum pedestals topped with plexiglass cubes. Cubes like this would normally contain objects, but David left them empty. The feet of small African-like sculptures could be seen peeking out from beneath the pedestals, all but concealed. The sculptures were amazing—David’s way of making something seemingly unremarkable look iconic. And I’ll never forget that when he came to Zurich for the installation, he was sitting near a window in the gallery chatting with a friend, and the art handlers asked how he wanted the works installed. He just said, “Oh, you do it. You decide.” It wasn’t as if he was giving no instructions. The instructions were that he wanted to cede control and see what happened. It was a very good experience with him. When I moved to New York in 2008, I started having meetings and lunches with Lois. I told her we’d be very into doing something again with David, regardless of what it was or where it was. And then in 2014 or 2015, Lois took me to his Yonkers studio for the first time. That was the beginning of a very long discussion that led to the show in Los Angeles.

Photo of David Hammons creating a basketball drawing, on view at Hauser & Wirth Downtown Los Angeles, 2019. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

Alex Bien-Aime (senior project manager, Hauser & Wirth): Once it looked like the Los Angeles show was really going to happen, I was assigned to be the lead art technician and, in 2019, I started regularly going up to David’s studio in Yonkers. It was the first time I’d ever gone to a big artist’s studio that wasn’t filled with a lot of assistants who are ultra-focused on the artist they were working for. David had just a couple of guys there who were good at construction and helped him build things in and around the studio. But they didn’t really seem like art-world people, and they weren’t worshiping him because he was a famous artist, you know? Mostly, David was able to pull off massive installations in his studio all by himself, without much help from anyone. It’s a huge studio, but it always felt like it was just him in there and sometimes Chie, his wife.

Tamar Nahmias (director of registration, collection services US, Hauser & Wirth): The first time I went up to the studio in Yonkers I didn’t even expect him to be there. But he was, and he answered the door. He’s usually the one who answers the door.

Berg: In January of 2019, Marc told me that David wanted to come and see the space here in Los Angeles. David came in February. We were told that he was coming for only a day, just for a few hours. I’d never met him before that day. He arrived wearing a pair of third-eye glasses, which makes it very tricky to read his face. We were all very careful about everything that day. The basic feeling was: “Let’s try very hard not to scare him off.”

Emma Wheeler (associate director, Karma, formerly Berg’s assistant): We were asking the guards to kind of hide him, so that nobody would see him and go: “Oh my God, it’s David Hammons.”

Photographs included in the Hammons 2019 exhibition. Left: Nathan Hunt at work, carving; right: David Hammons with Fannie Mayfield. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

Berg: He came by himself that first time. We weren’t sure he was really going to show up until he did. There’s a way that he interacts and moves through space that feels very ephemeral, like he’s a puff of smoke. He came, but I didn’t know how to contact him afterward or what to do next. He seemed interested, but you had the sense that could change quickly. I think Ian White, Charles White’s son, might have organized that first trip for him.

Russell Salmon (director, public programs and events, Hauser & Wirth): I kind of remember Stacen not wanting to say out loud that there was going to be a Hammons show, for fear of jinxing it or cursing it. It was like Macbeth. Don’t say the name. It had that Scottish play vibe.

Wheeler: Ian White is close to David, and at a certain point it became clear that he was the person to talk to if you wanted to get a message to David. There was so much mystery at first—we didn’t know if David had a phone, how long he was staying, how to contact him or when he would show up. It turned out he was staying in Venice, which is far from the gallery, but David has a deep history there. He wanted to be near the artists on the boardwalk; he would walk down the strip everyday to observe what they were making.

C. Ian White (artist and son of Los Angeles artist and teacher Charles White): My first memories of David with my father are from when I was very young. My father, David and Timothy Washington were in a three-person show called “Three Graphic Artists” at the Los Angeles County Museum in 1971. David tells a great story about that show, maybe his first institutional show in L.A. He was hitchhiking to the museum, I think up La Brea, and no one would pick him up. All these cars just going past him. And when he finally gets to the opening, in the galleries, he sees a bunch of the same people who passed him up on the road, and they realize he’s one of the artists.

Timothy Washington (artist): When David and I met each other, I didn’t know he was an artist. We both had jobs as custodians at the L.A. Department of Water and Power. I had no need to for the job because right out of high school I had won a four-year scholarship to the Chouinard Art Institute. But my mother worked for the department, and I wanted extra money to buy art materials, so I took it. We worked in the big, beautiful new building downtown. I liked David, and what we’d do is finish our shifts in a hurry, and then we’d meet in the drafting department rooms, and we’d draw together all night. When David found out that I went to Chouinard, he started showing up there. He’d just walk in and sit down in the classroom and start drawing from the models like everybody else, even though he wasn’t enrolled. One of the beautiful things about Chouinard is that they’d let you do that. If you wanted to be an artist, you were pretty much always welcomed.

Hammons and Alex Bien-Aime working on tent installation. Photo: Tamar Nahmias

Photo: Mario de Lopez

Berg: When David came to visit the gallery that first time, he didn’t talk very much. It was hard to tell what he wanted. He was just observing and walking through the space. I was pointing out everything that I thought might be interesting or relevant to him, but also just waiting for him to react. And then he said, “I’ll come back tomorrow.” And that’s the part that really stuck with me, because he wasn’t supposed to be there more than one day. But he ended up staying in L.A. for four days and coming to the gallery every day, usually just sitting on some benches we had along a wall, watching people come and go. He was always carrying a book that was very important to him, A Time for New Dreams by Ben Okri. Sometimes, I’d sit with him, and he'd have me read a passage from it. I asked him, “What are you looking at while you’re sitting here?” And he said, “I’m trying to figure out what kind of medicine these people need.”

White: In early 2019, I was co-curator of a show at the old Otis Art Institute campus (now Charles White Elementary School), where David—who was never officially enrolled, by the way—studied under my father in the late 1960s and early ‘70s. The show, “Life Model: Charles White and His Students,” had work by a lot of people who were in my father’s classes, like Kerry James Marshall, Ulysses Jenkins, Judithe Hernández, Suzanne Jackson and Kent Twitchell. I put a really early print David made at Otis in the show. David actually came to the opening, which is usually not his kind of thing. But he came, and we went to dinner, and after dinner, really late, like 12:30 in the morning, he says, “Let’s go look at the Hauser & Wirth space.” I said, “Now?” But he wanted to. So they open it up for us in middle of the night and we wander around. And either that night or the next night, we just go driving around, looking at streets around the gallery, Skid Row, all over downtown. Because a show for David is not just object-driven. He’s thinking about the space, he’s thinking about how new and existing works will interact, about how the work sits in the space, about whatever is happening around the gallery, out on the streets. He calls himself an urban archaeologist, something to that effect. So a lot of the time when you’re with him, you just wander around for hours. You’re looking for oddities and identifiers of whatever community or culture—or supposed culture—is evolving around you. He’s great at keying into that shit. He’s got a gift. I’ve seen a lot of people try to do it, but David’s different. He sees things that are easily overlooked. Things that, if you bring them to light, give you a different understanding of the world around you.

Payot: I got the sense early on that this was a show that was important to him because of L.A., because he had come of age there and hadn’t had a big show there in almost half a century. I don’t think he cared so much about the judgment of the art world, of what the general art world would think of it. It seemed to be much more about doing something for his friends and his peers in the city, about having the freedom to build a show into a kind of ultimate sculpture itself. It was never going to operate like a conventional exhibition. There was no checklist or price list. There were no dates and very few labels on works, except the work of others that he included in the show, like Agnes Martin, Jack Whitten and Dan Concholar. The commercial side of the show was very limited and came very late. It would have been OK with us if it had never happened. Most of the work was not for sale and came straight from David’s collection and went back to New York after it was over.

Maisey Cox (former senior artist liaison, Hauser & Wirth): As we got closer to the exhibition, David would continue to request certain objects including a giant red ball, a freezer, a rack of black clothing. The first time I met David, we looked at the book Going into Darkness: Fantastic Coffins from Africa, which depicts the Ghanaian burial process and these sculptural coffins that are made outside of Accra. The coffins shown in the book include cars, ships, animals, airplanes. They are meant to represent the profession or interest of the person who died. Shortly after his visit, David requested that we source one of these fantasy coffins in the shape of a rooster. Coincidentally, I happened to know someone who had just ordered a basketball-shaped coffin for Jonas Wood made by the artist Paa Joe, and I was put in touch. It was a very tight timeline for Paa Joe to produce and ship it from Ghana to L.A., but we made it happen. We weren’t sure what David would do with the rooster, but it soon became apparent that he wanted something that could respond to and comment on the gallery’s courtyard, where chickens live.

Rooster-shaped casket created by Ghanaian artist Paa Joe. Photo: Randy Kennedy

Photograph of artists at work on the rooster casket. Photo: Randy Kennedy

Ephraim Puusemp (senior art handler and technician, Hauser & Wirth): We were told he wanted the rooster in the garden, and we placed it there, but he wasn’t happy with it. He didn’t know what he wanted to make it feel complete. And then one day he told me, “It’s a chicken. It needs a coop. Build a fence around it.” So we got wood and chicken wire and built a fence.

Berg: I think he was waiting for some constraints to be put on him. And if we just kept saying yes, then there was nothing to fight against. Our approach was: “We’ll do anything you want. If you want that space, you can have that space. You want all the spaces? You want the courtyard? You can have it.” I mean, he also carried around a book titled Tell Them I Said No, by Martin Herbert, about great artistic refusals.

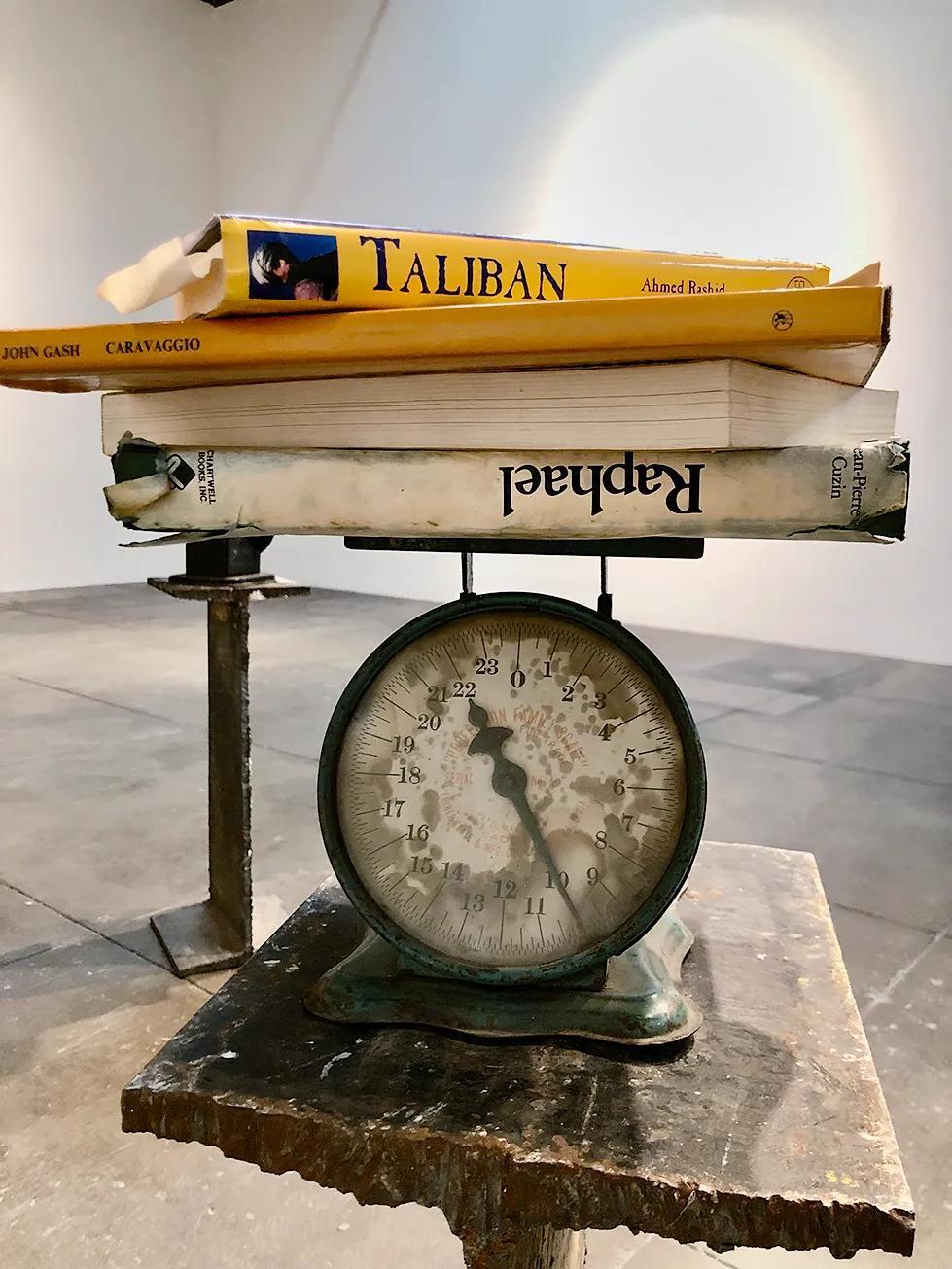

Bien-Aime: One thing he wanted for the show was some asphalt chunks. But it couldn’t be just any asphalt. David has an old studio in Harlem in a storefront space, and he asked us to go there and go down into the basement and shovel out some asphalt to send to L.A. So I went with Ben Phelps, our head technician, and he and I grabbed shovels and went down into that basement and dug up that specific asphalt, sourced from Harlem, and put it in contractor bags and shipped it out in C-bins. In the show, it was mounded on the floor with two of his big, framed basketball drawings rested on top of it.

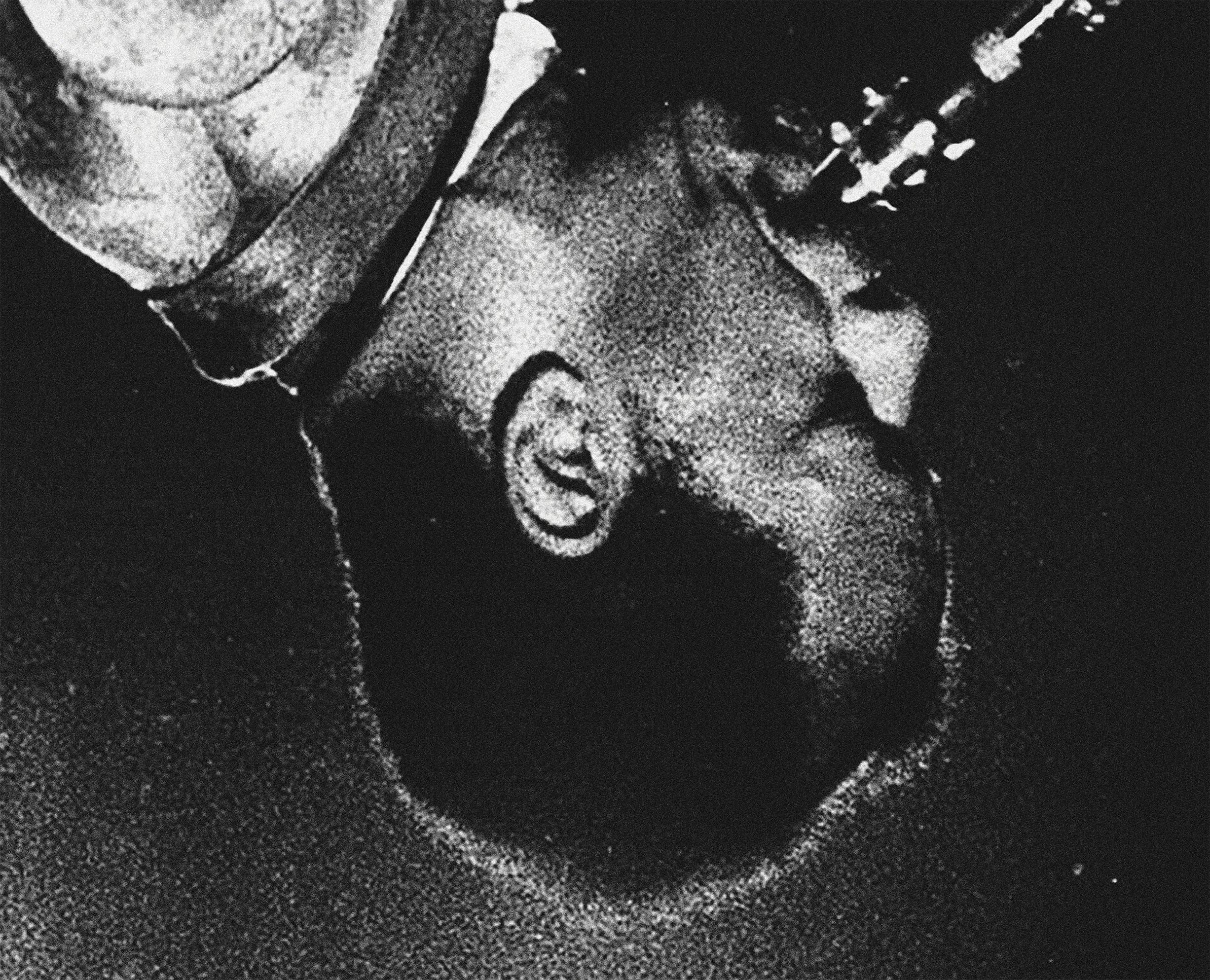

White: Something you need to understand about that asphalt is that it’s not just asphalt. It’s the court. It’s the surface where basketball is played on the street in New York, in cities. David has a fascination with things like that, with the surface of the city. One time years ago, I was in New York with David and John Outterbridge. We were going around the city and David was giving us tours of some places. And downtown, near Cooper Union, David was like, “OK. I want to show you guys something.” And he says to me, “Go into that Duane Reade pharmacy over there and get me a toothbrush.” I was thinking, “What the hell does he need a toothbrush for right now?” But I parked the car and bought one and then we walked over to a little hole in the sidewalk and he’s like, “Give me the toothbrush. I’m the curator of this project.” He takes the toothbrush and cleans leaves and trash and gunk from around the hole and has us get on our hands and knees and look down into the hole and there’s a crazy sculpture down there that looks like a miniature city. Someone else had done it—who knows who—but somehow David had become became privy to it. He had appointed himself the caretaker of it.”

Berg: A lot of the install felt spontaneous—like an improvisation. And at a certain point we began to understand that Ornette Coleman was becoming the presiding spirit of the show. At first, David said he wanted to include a few of Ornette’s old suits as objects. Then he asked us to have a documentary dedicated to Coleman playing as part of the show. Ornette Coleman records were always playing as we installed.

Cox: At a certain point I think he just decided, “I’m going to have to state outright that the show is dedicated to Ornette Coleman because none of you seem to be picking up on it.”

Autumn Beck (freelance art registrar and consultant, formerly head registrar, Hauser & Wirth): The Ornette Coleman concept of “harmolodics” and harmolodic thinking was a huge part of what it felt like David was trying to do with the show, or at least it seemed that way to me. And music overall was such a big part of the experience of working with David during the install.

View of a work in the 2019 show. Photo: Randy Kennedy

Detail of Untitled (Basketball Drawing), 2014. Charcoal and dirt on paper with asphalt, 134 x 46 x 3 1/4 in. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

Denardo Coleman (jazz drummer and son of Ornette Coleman): I don’t know quite how far David and my father went back. The first time I remember meeting David was when we had a party for my father at a good friend's house in Harlem, in one of the brownstones on Strivers’ Row. David and I reconnected in 2017 when we had an Ornette festival at Lincoln Center, which he came to. We have a mutual friend, the documentary filmmaker Manthia Diawara, and at some point Manthia contacted me and said David was going to be having an exhibition and wanted to dedicate it to Ornette and wanted to come by and talk. There was a lot that my father and David have in common, in part both of them going to Los Angeles as young men—as opposed to going to New York. David came from Illinois, and my father from Texas. They had their own energy going on out in Los Angeles, and more space to create their own thing. David came to see me a few times here in New York, and I went to visit him in his studio. It was a long process. We got to know each other and talked about a lot of things. What my father did creatively and where he was at philosophically, it just seemed like he and David aligned. In jazz, when you’re coming up, you have a soloist and they’re soloing off of a kind of determined harmonic map. But my father was asking: “Is the map more important or the solo?” And then he decided: “Let me figure out how I can just invent a map as I’m going.” And that became his thing. It’s why his music still sounds so fresh with ideas. Because for him, it’s just idea after idea.

Puusemp: Installing, we were listening to a lot of Coleman, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins and Coltrane, and also to reggae and African music. There was a really great moment that resonated with me. We were trying to place a key piece in the gallery and finally got it exactly where David wanted it. He was really happy and he quoted a lyric from a song: “Knock and it shall be opened / seek and you shall find / that wisdom is found in the simplest places / in the nick of time.” And I knew the line because I like reggae and we had talked a lot about both of us listening to it. That line was from Bunny Wailer’s Blackheart Man. David had this really incredible way of expressing his satisfaction with something when he got it right. He would just be like, “Phew.” Like it was lucky, like it might not have happened.

Cox: In those moments, there was always a little grin.

Wheeler: Sometimes if we were on a tight deadline and behind schedule, he’d just say, “Don’t worry. It’s going to be OK.” There was a kind of flow mentality that he had, but the flow could also be disrupted. If he met someone he didn’t like and ended up having to talk to them, he’d have to go lie down afterward, have a glass of water. It would wear him out. He’d use the third-eye glasses as a kind of protective device. He’d wear them when he didn’t want to talk to someone.

Beck: If you were overthinking something or stressing out too much, he would say, “The best tailor makes the fewest cuts.” And if you got too excited about something or thought something was too funny, he’d say, “OK, alright. Bring it down a little.” It almost feels like part of the install was him coming out to educate us. The one memory that sticks with me is a few of us going on a field trip one night to Timothy Washington’s house and studio in Leimert Park. The whole house is like a sculpture—there are objects and work everywhere. Earlier that day, David had asked me to bring in some things from home for the exhibition. I had a bunch of small bells at home that I brought to the gallery, and David put them in his pocket. And then we get to Timothy’s, and there was a huge sculpture he had made that looked like it was part horse and part giraffe. Like a lot of Timothy’s sculptures, there were bells and other sound-making objects on it. That night, Timothy starts to play the sculpture for us and then David takes the bells out of his pocket and starts to ring them. Timothy’s like, “Who was ringing those bells?” We pointed at David. Timothy goes, “Let me see them.” And then he said, “Wow, I’m so excited.” David said, “I brought them for you.” And Timothy took them and there was one part of the sculpture that still looked unfinished, a hole near the midsection and he put them inside and said: “These are the bells for this hole.” Unbelievable stuff like that happened all the time.

Washington: David and I have always found bizarre little things, objects and pieces, and given them back and forth to each other as gifts. That piece, Futuristic Animal, was something I worked on for many years. It has bells, rattles, a bunch of noise-making elements accessible. Each time I play it, I’m able to play it better and better. I’m sure that when Hendrix first picked up a guitar, he didn’t pick it up and play it behind his back and all that kind of stuff. I’m learning to play this sculpture like a guitar and I’m getting better at it. Objects have always called to me, from different parts of the earth. Everything is alive, to me, in some degree, and if you bring certain objects together you have more power in your work. David and I both do that. On that particular night, he gave me his bells and I put them inside the stomach of the animal, so they could be ingested. They needed to be ingested.

Hammons with his work at the exhibition “Three Graphic Artists: Charles White, David Hammons, Timothy Washington,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1971. Digital Image © Museum Associates / LACMA. Licensed by Art Resource, NY

Portrait of jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman. Photo: Elena Carminati

Berg: Something that really stood out to me as David was planning the show was how carefully he designed the space. He planned exactly how he wanted the different spaces in the gallery to work and how people would experience them. He installed a lot of walls, which he used to move you through the space in a particular way. He wanted to create intimate experiences with lots of artworks, but also to set up really complex angles and sight lines. People moved through the galleries in a way that allowed them to see things from many different perspectives. Then the courtyard really came into his thinking, and he said that it had to be part of the show.

Cox: At one point, didn’t he say that he just wanted ice out there—a massive block of ice in the middle of the courtyard that would melt during the run of the show?

Berg: He did, and we had to try to figure out how much water that would create and whether it would flood the galleries. But then, pretty quickly, he seemed to settle on the idea of covering the courtyard in tents, a reference to Skid Row. That was something we had to discuss with Iwan and Marc. We had to ask ourselves: “Is this OK? How are we going to contextualize this? How will it be received in a big gallery like this, so close to Skid Row?” Again, it was a moment of David challenging us, as if asking, “Are you going to say no to this?” I think the slogan he put on the tents— “This could be u and u”—went a long way toward making it clear what he was trying to say about the precariousness of stability in everyone’s life.

Elizabeth Portanova (director, marketing and events, Hauser & Wirth): During the press preview, it was pouring rain and here were all these people taking pictures of a field of tents, and it was a very stark, weird scene. The feeling of everyone looking at the tents that day seemed reverential, almost kind of sad. It seemed like the reaction was really about the work and about what was happening in the city, in L.A. It was pretty powerful for me.

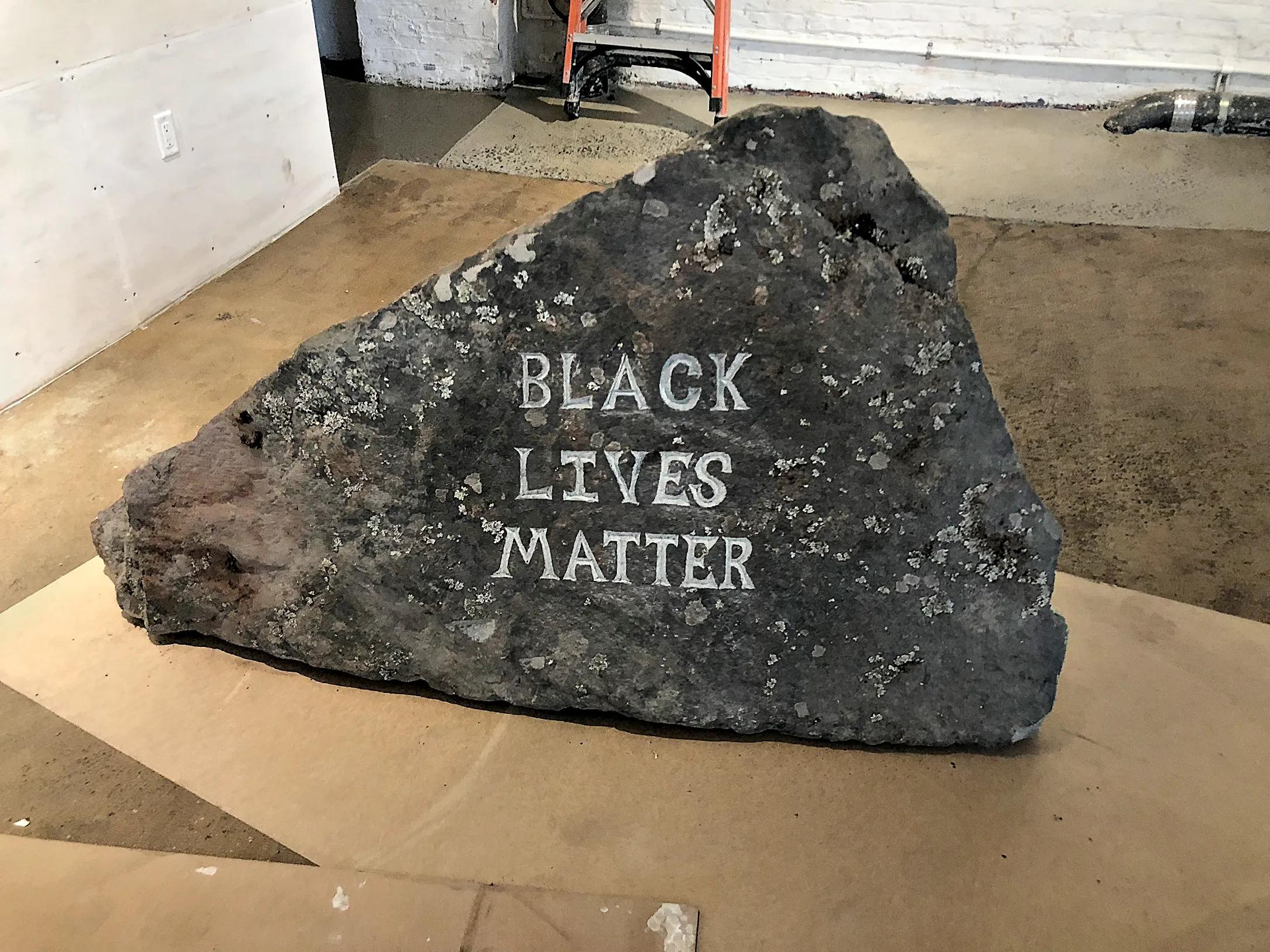

Wheeler: Before you entered the building, you encountered “Black Lives Matter” permanently carved into the exterior landscaping rocks. David was establishing a mood that permeated the entire space, extending beyond the exhibition walls.

Berg: On one of my visits to David’s studio in Yonkers, I saw that he had rocks with the Black Lives Matter statement carved into them. He sent a couple of those to L.A., but he really wanted to have someone carve it onto our rocks, the existing rocks that we have around the gallery and the courtyard. And we found this guy, Nathan Hunt, this amazing human being, who was so good not only at his craft but at how he approached the whole process with David.

Nathan Hunt (artist and owner of Hunt Studios, Los Angeles): I’m not quite sure how they found me. I’m a sculptor and my business is architectural carving and also art fabrication. Rock carving is a kind of rare craft, particularly in L.A. There aren’t many of us, and I guess word of mouth, or the internet, must have led them to my door. The request was to do an engraving on site with the inscription “Black Lives Matter.” They sent a simple graphic and we went through different fonts and layouts. First I did a test carving, to make sure I knew how to work with the kind of stone it would be. It’s kind of funny. I did a little piece of Morse code, just to show them what the engraving would look like on that kind of rock. It’s still out there somewhere—dot dash dot, on a little rock in the garden. Then I did a sample with the real inscription and met with David a few times. He told me he wanted me to do a live carving during the opening. I actually did it in a suit, which I suggested to David. I thought of it as a performative action, an action of service. And he liked that idea. I probably should have had a briefcase with my chisels in it, too. Getting down on your knees in the dirt in a garden and doing that—I mean, I do it all the time, because it’s my craft, but this felt like a different kind of thing. It felt good. And I love the idea that these rocks live on as artworks of his and that I was somehow involved.

Black Lives Matter rock carved by Nathan Hunt for the 2019 exhibition. Photo: Tamar Nahmias

Patrisse Cullors, a founder of the Black Lives Matter movement. Photo: Noé Montes

Patrisse Cullors (artist, activist and co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement and Crenshaw Dairy Mart art collective): We went to one of the previews, I think, before the big opening, and I’d never met David and he walked right up to me and said: “I’ve been looking for you.” And then he said, “Come here.” And we walked over to one of the carved rocks, and he said, “Do you want one of these?” Of course I said yes. And it’s right here at the Dairy Mart with us now. We’re its hosts. The whole thing was just beyond. I think it was also a moment when I really realized the impact of the work that we’ve been doing. For a hero of mine to use this call to action for one of his works and then to gift it back to us—I don’t even know how you express that kind of gratitude.

noé olivas (artist and co-founder of Crenshaw Dairy Mart): The rock has become like a cornerstone for us here. It’s also one those things in your life that makes you think. “OK, yeah. I’m in the right place. Exactly where I’m supposed to be.” It’s just one of those signs. For artists, I think the Hammons show felt like one of those historical landmarks, a thing you’re going to tell your children and grandchildren about, kind of in the way, I’m sure, people of a previous generation talked about the Duchamp retrospective when it came to the Pasadena Museum in 1963.

Wheeler: We didn’t know why at first, but before installation began, David insisted we order him a conductor’s wand. We quickly sourced one from a music website, but the moment he received it, he said, "No, it’s the wrong weight." Understanding the level of attention to detail even within his improvisations, we ordered a more suitable wand. And the conducting of the installation began.

Berg: We all sort of forgot about it, and then all of a sudden, when works were being installed, the wand would appear.

Wheeler: He always had it in his pocket, I swear.

Hammons conducting workers during installation. Photo: Maisey Cox

Berg: I remember during the placing of the Black Lives Matter rock, there was this very dramatic moment. The rock was so big and heavy, and it needed multiple people to lift it, to get the placement just right. And while all of that was going on, we saw David near the rock, with the wand, conducting the whole procedure.

Cox: He leaned over to me and whispered, “Get my picture.” So I documented the whole process. Later he had me print one of the photographs and he placed it in a vitrine with some other photos and objects.

Puusemp: He carried the baton throughout the install and exhibition. Numerous times during the install, he was moving through the space with it in his hand, like a conductor.

Salmon: The day that the Black Lives Matter rock was scheduled to be installed, there was some kind of corporate brunch in the garden at Manuela [the restaurant located at Hauser & Wirth Downtown Los Angeles], a bunch of tables of important-looking people sitting outside right near the courtyard. And when David saw them, he said: “Get the crane. Let’s do the rock now.” So there were all these people moving the rock and David with his conductor’s wand. And all the brunch people were looking over, like, “What the hell is happening here?” I was just bowled over with joy. I thought a lot about the conductor’s baton. In 2021, in the same courtyard at the gallery, we staged a re-envisioning of David’s famed performance work Global Fax Festival, which he had originally done in Madrid in 2000, a piece dedicated to the composer and conductor Butch Morris. And I think David’s use of the wand had things to do with both Ornette Coleman and Butch Morris, who pioneered a style of improvisational musical performance that he called Conduction. The conductor’s baton just seemed like the perfect tool for David.

The artist Timothy Washington in his studio with Futuristic Animal

Silk suit worn by Ornette Coleman, on view in the 2019 exhibition. Photo: Mario de Lopez

Puusemp: By a certain point into the installation, I feel like he had kind of picked his people, the people he wanted around him. A group of us just sort of formed, and we were the Hammons people. It was a long install, and there were lots of long days. There were periods when we had crews here to do certain things, move certain things. We were working through the weekends, and we would try to cater lunch for everyone when we were doing a weekend install. One day I asked David what he wanted for lunch. And he said “No, I’m buying lunch. Go tell Manuela. Get the dining room ready.” It was like twenty of us, on one of the restaurant’s busiest days. And we all sat down and had this long, leisurely, wonderful lunch. It was really special for all the people on the team who were working with him to be acknowledged that way.

Fannie Mayfield (longtime Downtown Los Angeles resident): Some people I know on Skid Row told me that a man named David Hammons had come around and met some folks and had done some good things for some of the people there. So I went to the gallery to see if I could meet him. For fourteen years, I lived on the street near the gallery, in a cardboard box and later in a tent. I’ve had an apartment now for fifteen years, but I still like to come over here and ask if I can sweep or wash windows or do any other help to earn some money. One afternoon I went in and asked if David Hammons was there and they pointed to him, and I walked straight up to the table and introduced myself. And he talked to me and hugged me and we just kind of spent time together. Sometimes the people that come in to give a show at the gallery, they’re very private. They don’t even like to be around the people that they invited. But I took the chance to just go in there and meet David Hammons myself, just to see what kind of person he really was. And later he had them take a picture with me, and when I went into the show after it was open, there was the picture of the two of us, taped on the wall! I went to the show a few times and took my time in there walking around. A lot of my dreams were in there, things that I never could accomplish. I saw a lot of my own life in that show, with my naked eye.

Berg: I remember at the opening David saw Fannie and took her around with him and told someone to get them glasses of champagne.

Payot: It’s difficult with David to really know how much he enjoys something, or what he enjoys. The day before the opening, we asked him if he would come to the opening in person, something he normally doesn’t do. He’s legendary for not appearing in those situations. He said: “I don’t know. I’ll think about it.” We told him that if he wanted to be there, we could set aside a private dining room at Manuela where he could stay and receive friends and not have to be out in the crowd. He gave us a whole list of people he wanted us to invite. But then when he arrived, he never went into the private space. He was out in the courtyard all night talking to friends, meeting people, showing people around, being very public. There’s a wonderful picture of him and Betye Saar together that night, holding hands.

Berg: Right before the show opened, I remember David saying that the gallery shop right off the courtyard bothered him. It was a store with high-end goods and design objects, and he said the energy bothered him. He talked for a while about turning it into a healing center. As usual, we were open to anything. We were ready to say, “OK, we need to do that.” But it all kind of settled down into, “The energy is just off, and we need to set it right,” and he asked us to find a psychic healer to do a cleansing of the space. It was a monthlong process, vetting people, presenting them to him, finding different types of healers. And we finally found a woman who specializes in this kind of thing, cleansing space. We gave her information and history about the buildings, and I was on the phone with her, moving around the spaces here, and she was clearing them for us. She said the basement was particularly dark, that it had some stuck energy.

White: Does David believe in things like that? Let me put it this way. We’ve all seen that conventional wizardry doesn’t work. Otherwise, the world would be different, wouldn’t it? So David likes to try unconventional wizardry.

Bien-Aime: Energy was a big thing for him, having the right energy around him. I realized I had to spend time a lot of time with him and with the work to understand it. And fairness was also a big deal. He wanted everyone treated fairly. He knows how big this gallery is and what it can do and how everybody should be treated.

View from the 2019 exhibition. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

View from the 2019 exhibition. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

Cox: David continued to change things throughout the show. He would come by the gallery and then we would notice that things would be moved or new things would appear, like Kool-Aid packets and crumpled-up dollar bills.

Wheeler: We had to keep getting new photography inside the galleries because that would always happen. The show was never stable. With the stuff on the floor, you couldn’t tell what was what. We’d ask each other: “Did some kid drop this stuff? Did David put it here?” He kept messing with the question of whether something was art or not.

Nahmias: The confusion is part of his work. It’s not like there are no rules. There are rules, but you have work to uncover them. It’s something that you learn while spending time with his work or spending time with him. You gain a deeper understanding of it. It’s certainly not the norm when you’re dealing with artists and artwork that’s incredibly precious. Usually, you don't really want any confusion. But I think he enjoys it.

Puusemp: We started making notes about where he dropped the money and telling the guards that it was not supposed to be moved, that it was part of the exhibition. And then David found out, so we had to tell the guards not to stop people from picking up the money. He wanted to see if people were picking up the bills and taking them home. It was a whole thing.

Berg: The guards told us that some people left their own money, too, like an offering. The whole show was an evolving blend of activity, like a performance. David was here for a lot of it. And there were people who came back again and again and saw it change.

Puusemp: He wanted to be here for the majority of the deinstall as well, which is pretty rare. Most artists don’t do that, but he was very present for it. I had a sense that he had such a personal connection to the objects in the show that he wanted to see them moving through the world, being installed and also being packed up. He had a camp chair out under a tree in the courtyard. He’d just sit there, reading, watching people, watching things go from the gallery back into the trucks.

Berg: David really poured his whole self into this show. It was the closest thing to a retrospective that he’ll probably ever want to do. And I think it was deeply personal for him. None of us will ever forget it.

–

This oral history comprises interviews conducted in person or by phone between December 2023 and May 2024. Responses have been edited for clarity and concision.

Autumn Beck is an art doula and collection manager based in Los Angeles.

Stacen Berg is a partner and executive director at Hauser & Wirth.

Alex Bien-Aime is a senior project manager at Hauser & Wirth Collection Services.

Denardo Coleman is a jazz drummer and son of Ornette Coleman.

Maisey Cox is a former senior artist liaison at Hauser & Wirth.

Patrisse Cullors is an artist and abolitionist born and raised in Los Angeles.

Nathan Hunt is an artist and the founder of Hunt Studios, Los Angeles.

Fannie Mayfield is a longtime Downtown Los Angeles resident.

Tamar Nahmias is the director of registration at Hauser & Wirth Collection Services.

noé olivas is an artist and a co-founder of Crenshaw Dairy Mart.

Marc Payot is a president of Hauser & Wirth.

Elizabeth Portanova is the director of marketing and events at Hauser & Wirth.

Ephraim Puusemp is a senior technician at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles.

Russell Salmon is the director of public programs and events at Hauser & Wirth.

Timothy Washington is a Los Angeles-based artist and spirit-driven creator.

Emma Wheeler is an associate director of Karma.

C. Ian White is an artist, educator and advocate.

–

This article is part of a special section on David Hammons in Ursula issue 12, which also includes an essay by Linda Goode Bryant and a poem by Ben Okri.

"Concerto in Black and Blue," a new presentation of a 2002–03 exhibition by David Hammons, remains on view at Hauser & Wirth Downtown Los Angeles through May 25.

In May 2025, Hauser & Wirth Publishers released David Hammons, a post-exhibition catalogue devoted to the artist's 2019 show at Hauser & Wirth Downtown Los Angeles. Created entirely under the artist’s direction, the book documents the most expansive exhibition of Hammons's work to date.

Linda Goode Bryant is a social activist, gallerist and filmmaker. In 1974, she opened Just Above Midtown, a New York gallery that launched the careers of many Black artists. During the global food crisis in 2008, she founded Project EATS, an urban farming initiative. She is a Guggenheim Fellow and a Peabody Award recipient.