Essays

Testing Hypotheses

Performance, process and printmaking in the art of William Kentridge

By Judy Hecker

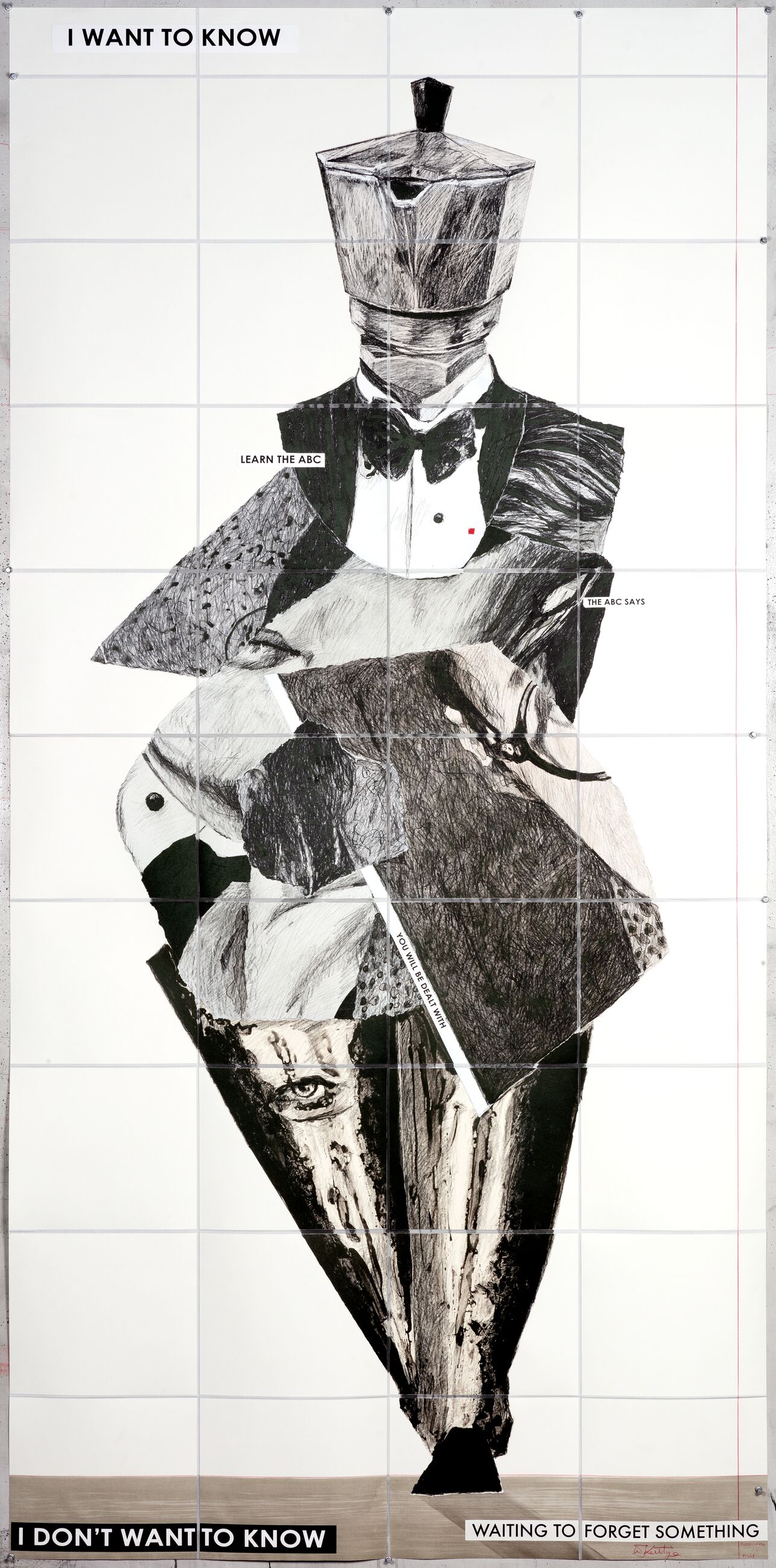

William Kentridge, Learn the ABC, 2024. Lithograph with watercolor, India ink and color pencil on Somerset Book and Zerkall Bütten mounted on cotton fabric. 228.3 × 112 cm. Edition of 20. Photo: Thys Dullaart

The genre-bending performance was unforgettable. Nearly twenty-five years after the fact, the exhilaration I felt while watching William Kentridge’s Zeno at 4 a.m. (2001) remains palpable to this day. The multimedia oratorio, presented at New York’s John Jay College theater, mixed actors with puppets and costumed performers who moved onstage in front of a procession of figures projected onto a screen. The shadows of the bodies onstage added their own live silhouettes to the screen. An upright form—ostensibly a pair of pliers with a paper head—moved in strides that matched the rigid movement of the tool’s handles. A half-tree, half-human carried a bundle of wood. A man dressed in a suit stood hunched over, his upper body enclosed in a cage.

Shackled yet triumphant in might, the mysterious igures were mesmerizing. When the lights came up, I wondered: Would I ever see these artistic humanoids again?

Kentridge made his home in experimental theater beginning in the mid-1970s. His creative work has always been steeped in printmaking, a highly lexible and durable medium. Known for a predominantly black-and-white palette, he has remarked that printmaking is a medium in which it is “legitimate to use no color, to work monochromatically.” Though some contemporary artists may view printmaking as archaic, the lines, tones and scrawls of etching, aquatint, spit bite, drypoint and photogravure—not to mention linoleum cut, screenprint and lithography—have offered Kentridge a visual language of endless possibilities.

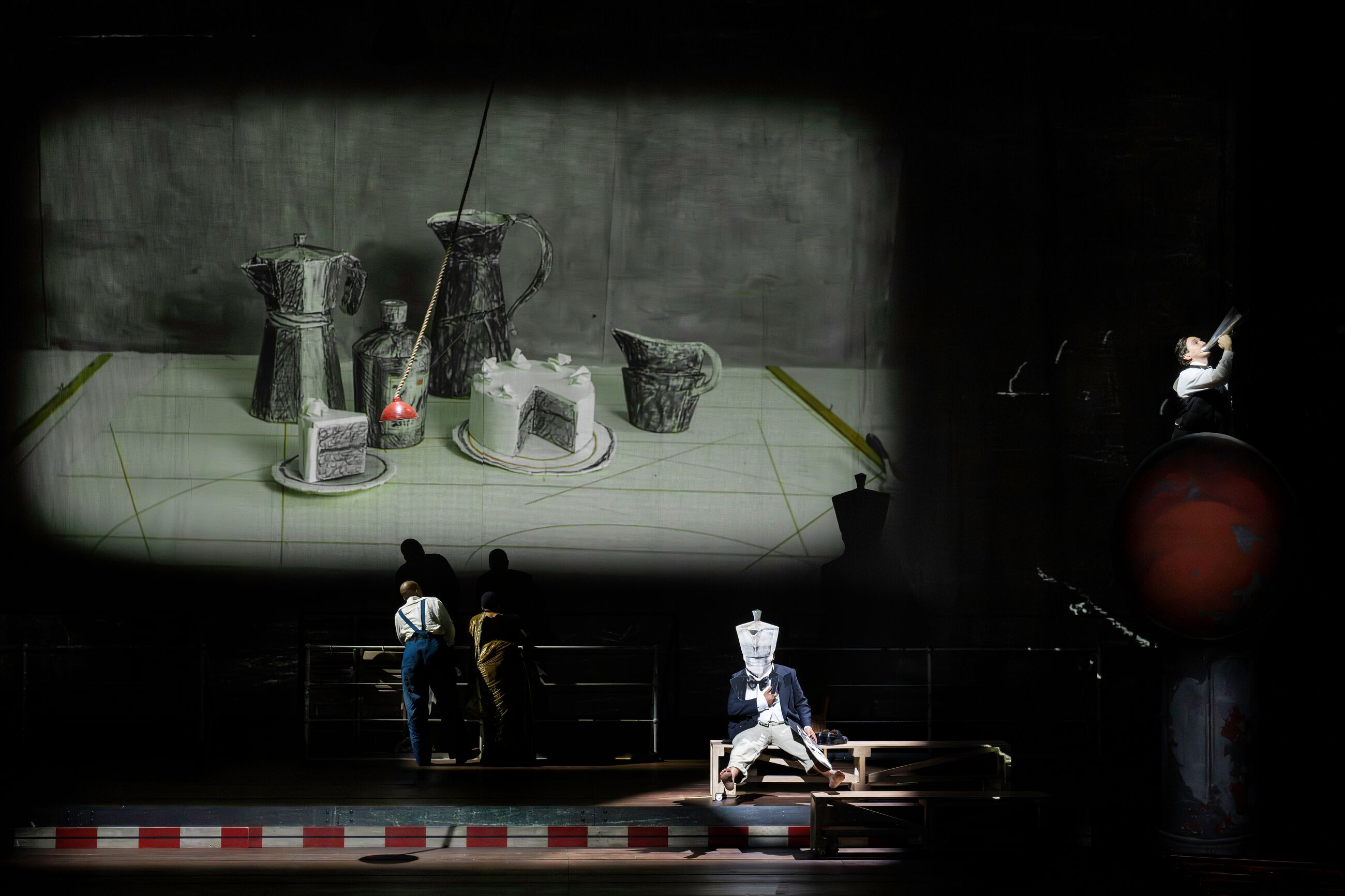

William Kentridge, theater production of The Great Yes, the Great No, 2024. Photo: Monika Rittershaus

Born in Johannesburg in 1955, Kentridge has, over the last fifty years, become one of the most highly acclaimed artists in the world, in demand as much in theater and opera as in museums and biennials. In addition to printmaking, his work includes drawing, animation, film, performance, sculpture and tapestry, much of it exploring the human condition during tragic periods in history as well as times of fervent artistic creation. Life during and after apartheid in his native South Africa. The Russian Revolution. World War II. Genocide in Namibia. His presentation of history is often layered, with elements of science, literature, culture and music woven in deeply, a surrealistic vision of contradiction, ambiguity and uncertainty that prompts more questions than answers.

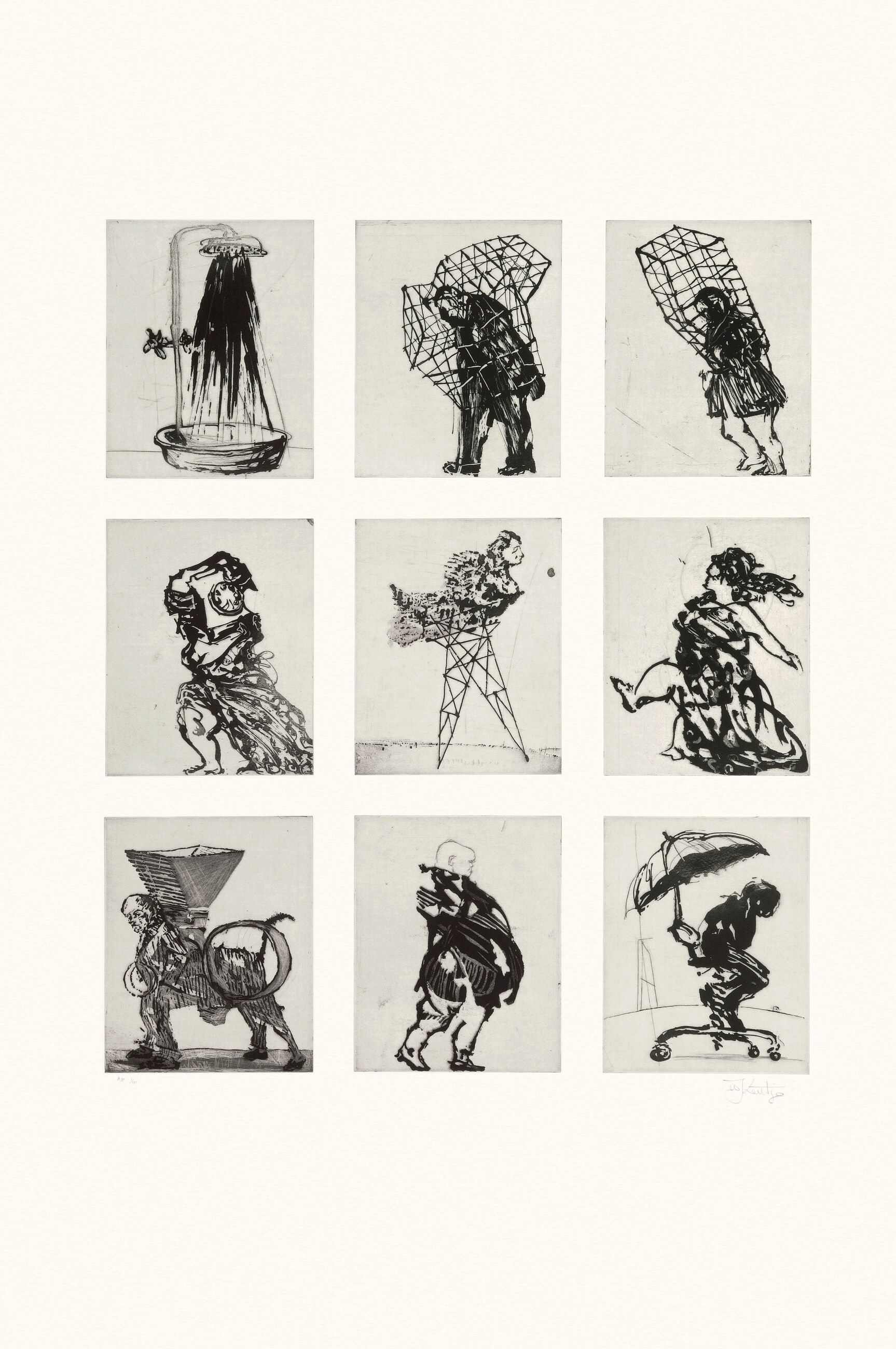

As it happened, my question about Kentridge’s humanoids had a satisfying coda: I did indeed encounter those equivocal figures again. Alongside the performance Zeno at 4 a.m., Kentridge developed a series of nine prints as part of a larger body of work and performances inspired by Italian writer Italo Svevo’s Confessions of Zeno (1923). The story, widely considered Svevo’s masterpiece, follows the self-analysis of the tormented but amusing titular protagonist. Many of the objects appearing in Kentridge’s suite of prints—telephone, electrical pylon, showerhead—are recurring motifs throughout his work, suggesting that he has at least partially conflated the history of the character Zeno with his own. In the intimately scaled series of aquatints and drypoints, the nine subjects feel as if released from their theater staging, with new movements and orientations; moreover, another version printed on nine individual sheets can be arranged in any configuration.

Shackled yet triumphant in might, the mysterious figures were mesmerizing. When the lights came up, I wondered: Would I ever see these artistic humanoids again?

The interplay of two- and three-dimensional work is a constant for Kentridge. Prints inform theatrical productions and vice versa. He has designed operas for the most coveted houses around the globe and has created prints at the beginning, middle and end of the process. As he told me, prints are very often “a way of thinking aloud. . . . There’s a sense that prints are for testing hypotheses, that the proposition and the conclusion are one of the essences of printmaking.”

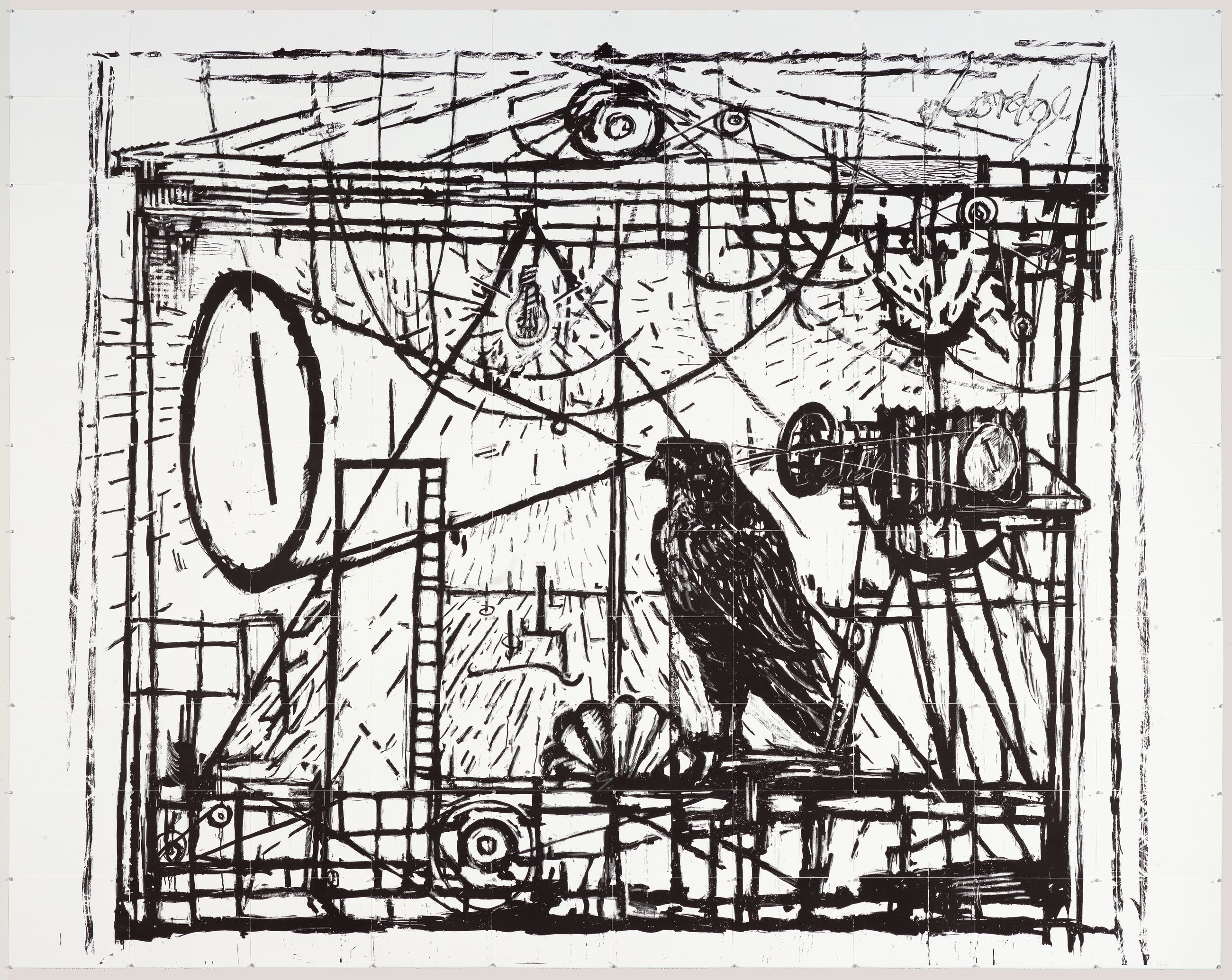

The very act of making—and displaying—a print can also be performative for him. Learning the Flute (2003) belongs to an extensive body of work Kentridge created while developing his 2005 staging of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. A monumental letterpress print—a sweeping nine-by-twelve feet—the work is comprised of 110 printed sheets, each mounted on two individual encyclopedia pages that have been extracted from whole sets. Every sheet must be arranged and pushpinned to the wall in a predetermined grid each time the piece is shown. Stored in a custom box, Learning the Flute is highly portable and, as Kentridge has said, “put together like a jigsaw puzzle.”

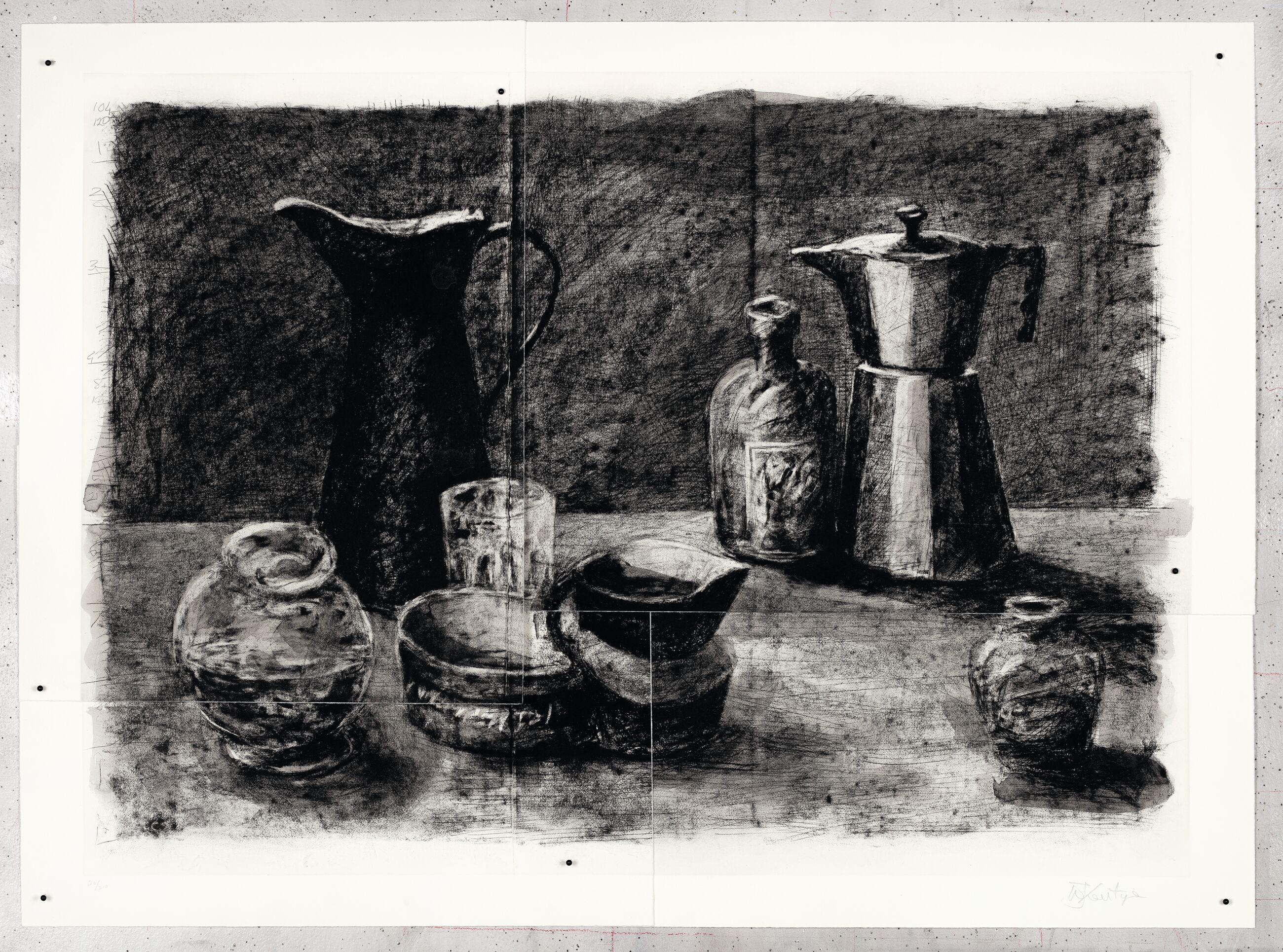

William Kentridge, Eight Vessels, 2021. Photogravure and hand-painting on four sheets of Hahnemühle, pinned with map pins. 73 × 99.5 cm. Edition of 20. Photo: Thys Dullaart

The overall composition, featuring an Egyptian temple, stage machinery, a falcon and familiar motifs, evokes the setting of The Magic Flute opera and mimics its grand scale. As if that wasn’t enough, Kentridge and his longtime collaborative printer, Mark Attwood of the Artists’ Press, created three companion pieces at that same scale, reversing coloration and mirroring composition (both with and without encyclopedia pages). Taken together, the four variations—a feat of printmaking, inventiveness and endurance—express the themes of lightness and darkness, day and night, good and evil at the opera’s core.

In the multipart linoleum cut Universal Archive (Twelve Coffee Pots) (2012), an anthropomorphized metal stovetop coffee-pot dances and evolves from sheet to sheet. As lines rearrange, images break down and reconstitute—is that a dancing woman? a man on a horse?—until the composition disperses into a calligraphic mark. Operating at the intersection of performance, drawing and printmaking, the result is radically improvisational. Of the process, Kentridge has observed: “Rather than saying, ‘I need to get one perfect coffee-pot,’ you make forty different coffee-pots. You take a simple image and see how far it can be reduced to a series of simple calligraphic marks before it disappears.”

William Kentridge, theater production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute, 2005. Photographer unknown

William Kentridge, Learning the Flute, 2003. Letterpress on 110 sheets of Arches Johannot (illustrated); and letterpress on spreads from Chambers’s Encyclopaedia (1950) on Arches (not illustrated). Complete print pinned with map pins: 281.6 × 354.6 cm. Edition of 18: 1/18 to 9/18 printed on Chambers’s Encyclopaedia, 10/18 to 18/18 on White Arches Johannot. Photo: Thys Dullaart

Twelve Coffee Pots is one of more than seventy-five prints that comprise Kentridge’s Universal Archive, a project that unites his images and motifs—coffee-pots, typewriters, cats, birds, trees and nudes among them. The archive is based on drawings that were converted to linoleum cut prints by a team at David Krut Workshop in Johannesburg over a four-year period. The workshop created the prints using exacting hand-carving methods under the stewardship of master printer Jillian Ross, a longtime collaborator of Kentridge’s.

Printmaking also meets performance in the singular life-size figure of Kentridge’s lithograph Learn the ABC (2024), which is based on a character from his newest performance, The Great Yes, The Great No (2024). The opera mingles fact and fiction, reimagining the real-life 1941 journey of a cargo vessel turned passenger ship, the Capitaine Paul-Lemerle, which transported refugees—writers, scientists, artists, activists—from Marseille to Martinique after the German invasion of France. The performance reinterprets the experience of the escape. The tuxedoed, coffee-pot-headed man in the print mimics the masks and collage used in the surrealistic stage performance.

Kentridge has observed: “Rather than saying, ‘I need to get one perfect coffee-pot,’ you make forty different coffee-pots. You take a simple image and see how far it can be reduced to a series of simple calligraphic marks before it disappears.”

The seven-foot print is an assembly of forty small, interconnected square panels. It can be folded down easily and stored in its jewel-like fabric box—unlike Learning the Flute, it does not require assembly. The work started as a single sheet of paper with layers of collage, but Kentridge and Attwood soon realized it would be impractical to transport, so they cut up the collage into separate panels and fabricated an attached grid that could be folded onto itself. The print’s portability also seems to allude to the movement of the characters across the stage and to the journey from one port to another.

Eight Vessels, a 2021 project, serves as a kind of creative midpoint in a four-year performative film project that Kentridge began in complete isolation during the pandemic. It became an investigation of still life, a centuries-old and often transcendental genre. Kentridge was in the unusual position of being alone in his home studio, without his assistants and longtime collaborators on hand, and he found inspiration in the still-life subjects that Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) produced obsessively for some fifty years in his apartment in Bologna. Kentridge rendered everyday objects around his studio with a similar impulse—water jugs, vases, an ink tin, a bottle of whiskey and of course, the coffee-pot. The work was created with the help of Ross as she was relocating from South Africa to Canada during the pandemic and in isolation from her own practice. Forged across two continents through WhatsApp conversations, the project ended up representing a journey of its own, conceived in a world in crisis.

William Kentridge, Zeno at 4 a.m., 2001. 9 etchings with sugarlift aquatint on 1 sheet of Hahnemühle. Each image: 24.5 × 19.8 cm; paper: 98.2 × 81.8 cm. Edition of 12 (illustrated). Related edition: Suite of 9 etchings with sugarlift aquatint on 9 sheets of Hahnemühle. Each image: 24.5 × 19.8 cm; each paper: 35.5 × 29.5 cm. Edition of 40 (not illustrated). Photographer unknown

Kentridge’s latest film project, Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot (2020-24), brings the viewer not only into the studio but, as it were, into his mind. It is an ode to the frustrations, messiness and uncharted waters navigated by all artists in their studios. During the making of the film, the genre of still life took many formats: maquettes, drawings, film animation and, eventually, the photogravure of Eight Vessels. The image is a steadfast presence in the film, appearing on the studio’s wall, subject to Kentridge’s subsequent erasures and contemplations. The film project developed into a nine-part series of thirty-minute segments that debuted at the Arsenale Institute for Politics of Representation in Venice in conjunction with the 2024 Venice Biennale and can now be streamed online.

In the first episode, A Natural History of the Studio, Kentridge observes slyly, as if summing up the driving engine behind his entire body of work: “You start thinking you’ll do a picture of the whole universe, but you end up with a coffee-pot.”

—

"William Kentridge: A Natural History of the Studio" is on view at Hauser & Wirth New York's 22nd Street and 18th Street locations through August 1.

Judy Hecker is the executive director of Print Center New York, a nonprofit exhibition space. Previously, she was assistant curator for drawings and prints at the Museum of Modern Art, where she co-organized “William Kentridge: Five Themes” (2010) and authored William Kentridge: Trace. Prints from The Museum of Modern Art (2000).

William Kentridge is internationally acclaimed for his artworks, theater and opera productions. He combines drawing and erasing, tearing, gestural painting, collage, weaving, casting, writing, film, performance, music, theater and collaborative practices to create works of art that are grounded in politics, science, literature and history.