Conversations

Repeat Into Eternity

Suzanne Bocanegra and Frances McDormand on Shaker design, song and communal care

In 2024, the Shaker Museum presented “CRADLED,” an experiential pop-up conceived and curated by artist Suzanne Bocanegra and actor/producer Frances McDormand at the Kinderhook Knitting Mill, New York. The exhibition highlighted the cradle, a fixture of Shaker households and an enduring emblem of life’s cycles. Historic examples—on loan from communities and collections from New England to Kentucky—were shown alongside a newly built reproduction of an adult-size cradle, in which elders, including the artist Joan Jonas, were gently rocked during the installation. The experience evoked the ethos of Shaker life: a radically simple devotion to respect and care, expressed through handmade objects, the rhythm of song and the discipline of daily labor.

That intimate debut served as the foundation for a larger staging of “CRADLED” that opened in Los Angeles in November 2025. The show extends McDormand’s and Bocanegra’s explorations of the ways in which objects and gestures of care can sustain communities in the present. The venue for the new staging is Make Hauser & Wirth, the gallery’s platform devoted to the contemporary crafted object. Since 2018, Make has highlighted the work of artist-makers across disciplines, with a focus on heritage, sustainability and emotional engagement with the handmade.

Ahead of the exhibition’s opening, Hauser & Wirth’s director of public programs and events, Russell Salmon, sat down with Bocanegra, McDormand and Jerry Grant, the Shaker Museum’s director of library and collections, to discuss the origins of “CRADLED,” the legacy of the Shakers and what it means to tend to one another in the 21st century.

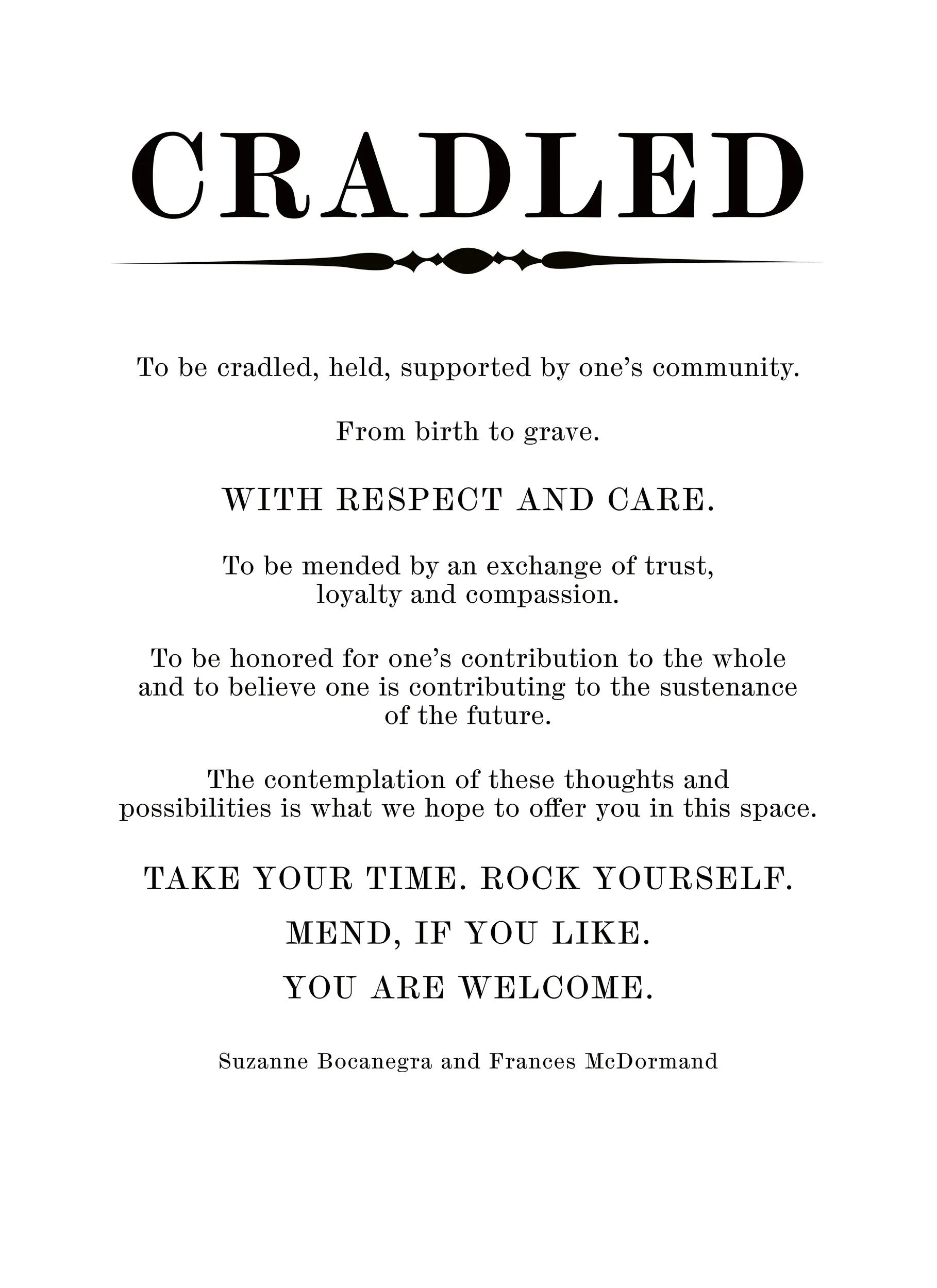

Suzanne Bocanegra and Frances McDormand, “CRADLED” manifesto, 2024

Russell Salmon: I’m so happy to see you all. This is a special moment to talk about “CRADLED,” and I’m just going to jump in and ask how each of you initially connected with Shaker culture. Was there a particular object or experience that first spoke to you?

Suzanne Bocanegra: For me, I had been reading about radical 18th- and 19th-century American communal movements for a performance I made, titled Farmhouse/Whorehouse. The Shakers, the Oneida Community, the followers of Charles Fourier and others all offered new visions of how to live. I was amazed how each began with a single individual who had their own proclivities and got all these people to follow them. The Shakers were founded by Mother Ann Lee and are particularly notable not only for their celibacy but also because they were founded by a woman, which made them different from the get-go. They also developed a distinct aesthetic in design and craft that many of the others did not. That unique visual legacy is why people remain interested in their objects today.

Frances McDormand: I first connected with the aesthetics of the movement—the furniture especially—and the simplicity of it. Then I did a workshop with the theater director Martha Clarke, who, along with the playwright Alfred Uhry, was developing a piece on Mother Ann Lee and how the early Shaker community formed in Manchester, England, and then moved to America. In that workshop, I got more interested in the details of its matriarchal inception and its early believers. Later, I did another theater piece with the Wooster Group, who I had worked with before and wanted to work with again. I was having dinner with Kate Valk, one of the founding members of the company, and she said, “What do you feel like doing?” And I said, “I don’t know. I really want to sing—although I don’t have a trained voice—and I want to wear a Shaker bonnet.” [Laughter.]

RS: That’s amazing.

FM: It was great. We developed a piece called Early Shaker Spirituals that was based on an album recorded in the 1970s by a group of Shaker women at Sabbathday Lake in Maine who preserved songs that had been passed down through oral tradition. That project was about ten years ago and it led me to Mount Lebanon, New York—the historic center of Shaker life—which is where I met Jerry. And we’ve stayed in touch ever since, right, Jerry?

Jerry Grant: Ever since! I remember we first met when Fran came to do research in our archive. Then we invited her to sing a few songs at a benefit for our new museum in Chatham, New York, and everything has grown from there.

FM: Last year, Jerry and the museum invited me to curate something at a pop-up nearby in Kinderhook. I said, “I don’t know enough to do that, but my friend Suzanne Bocanegra does.” So I got in touch with Suzanne, and that’s when we all gathered forces.

SB: That’s right. And it turned into the first staging of “CRADLED.”

JG: We had multiple Shaker cradles, both child- and adult-size, including a newly built reproduction of an adult cradle. Each cradle was arranged with its own rocker, mending basket and lamp. Some of the historic cradles came to us on loan from Shaker villages in Kentucky, New Hampshire and Massachusetts, as well as from John Keith Russell Antiques in South Salem, New York.

SB: Did that Martha Clarke piece ever happen, Fran?

FM: It did. And it was interesting.

Sisters Martha Jane Anderson, Grace Bowers and Anna White in the North Family Sewing Room, Mount Lebanon, New York, 1890–1910. Courtesy Shaker Museum

“We associate cradles with the beginning of life, so to see them adult-size can feel strange and even a little disorienting at first. But it’s the same soothing sensation as when you rock a baby to sleep. It’s connecting the early time of birth to the end of one’s life.”—Suzanne Bocanegra

JG: It was called Angel Reapers. I remember seeing it in New York City.

FM: Though I will tell you, I started moving away from Martha and Alfred’s concept for the piece, because they both felt that Shaker life was very restrictive and could not be successful because they did not have sexual congress—although 200 years as a community seems like a lot to me. I thought that perspective was really kind of narrow-minded, I have to say—and I don’t mind that being in print.[Laughter.]

RS: Jerry, how about you? How did you come to the Shakers?

JG: I graduated with a degree in history education but quickly realized I found political history dry. I was drawn instead to social history and how people lived. Reading about the Transcendentalists led me to communal experiments like Fruitlands, and eventually to the Shakers. What fascinated me was the richness of their daily routines—how they cooked, built, cared for their homes and families. These were common people living an uncommon life, and that contrast was very interesting to me. I got into Shaker crafts and trades, and it just opened up from there. And now, forty-seven years later, here I am—still Shakering.[Laughter.]

SB: Shakers really are so focused on the day-to-day, like keeping the house clean and what kind of room to make.

FM: That’s what I love about the music. So many songs passed down through oral tradition were about work. There were songs for praise but also songs just to get you through a day of cleaning, sweeping, planting, washing dishes. There’s a real sense that once you start making that music together—when you start singing together—it bonds you toward a goal. And I like to think of all of us talking here today as Shaker adjacent. We may not be living in a purely religious Shaker way, but we are certainly honoring part of their life, the way they led their lives.

SB: And it’s still very much alive. There are different Shaker museums all over and people are collecting their objects and singing their songs.

RS: It makes me think about the manifesto you all wrote for the exhibition, which is central to the show both physically and thematically. I’m curious about the genesis of it.

SB: What’s amazing is that Fran wrote the manifesto exactly as it appears in the show. She said, “I’ve got what I want to say,” and when I saw it, my reaction was, “I wouldn’t change a thing.”

RS: Part of the manifesto that really resonates with me is the proposal of respect and care for others, especially through the act of cradling your community members. What does that concept mean to each of you, especially right now?

FM: I was not present at either of my parents’ deaths. But a few years ago, I was with a dear friend in her last days, which I think healed some of that regret—especially about not being with my mother. It gave me the chance to learn from the process of being with someone at the end of life. In our modern world, we often don’t get to prepare for what we hope our own passing will be. I think part of the manifesto for me was acknowledging that I’m preparing for it.

RS: And it encourages other people to do that, too.

FM: Right—not just for your parents or the elders in your community, but for yourself.

SB: We associate cradles with the beginning of life, so to see them adult-size can feel strange and even a little disorienting at first. But it’s the same soothing sensation as when you rock a baby to sleep. It’s connecting the early time of birth to the end of one’s life.

FM: In our first staging of “CRADLED,” we rocked elders and we were also rocked. There was something about that—not just to be rocked, but to rock someone—that goes back to the Shaker philosophy of being able to serve.

JG: What has impressed me about the whole “CRADLED” experience is that it’s not just leaving somebody to comfort themselves. You have to be present for it to work, much like rocking a baby, and it really connects you with that person.

SB: Respect and care are two things I find so attractive about the Shaker community. I have a performance about a 16th-century tapestry, titled Honor, which made me think about the word itself. Some of the philosophers I read said honor is often used to set one group above another, and it should be replaced with dignity. Respect and dignity for everyone feels so noticeably lacking right now.

RS: We’re bereft.

FM: Exactly—we are bereft. One of the things I love about the Shakers is that when they were planting for themselves—they were an agricultural community, though also entrepreneurial in many ways—they would also plant for the larger community. They planted enough to be able to sell and make a profit, but they would also always plant enough for those in need. They knew that was a necessity, so they built it into their agricultural schedule.

RS: Was that their main form of commerce? Or were they selling their goods outside the community to sustain their livelihoods?

JG: Well, the Shakers were great entrepreneurs. In a community of several hundred people, if you needed 200 chairs, by the time you made them you had the capacity to make 200 more. Doing things in large quantities meant they developed the machinery, tools and skills to keep producing—so why not sell some? Even though they lived outside what they called the “common course of the world,” they never expected to be totally separate. They had to buy certain things, so they sold what they made to be able to do so.

RS: Did that aesthetic come out of the need for things to be simple, so they could continue to manufacture them?

JG: I think something close to that. There was no use in adding a lot of time and labor just to make something that was pretty in the eyes of the world. In the early days, it was practical things—spinning wheels, cards for combing wool, packaging garden seeds. All pretty standard, practical items that didn’t need decoration to sell. Later on, in the Victorian period, you do see Shakers making things more in a worldly style.

FM: Going back to the cradling and the rocking—when Suzanne and I rocked the artist Joan Jonas, the cradle we used was a replica, a beautiful thing. It was built by Boyd Hutchinson and signed on the bottom by all of us who worked on the original “CRADLED.” But when we rocked her, we realized the rockers don’t really work that well. We could pull her toward us, but not necessarily get a smooth, continuous rock back and forth. So we’re going to work on that—always good to have something to work on.

JG: We have to tune that cradle up. [Laughter.]

“I think of Brother Arnold Hadd, one of the three living Shakers, who often says celibacy wasn’t the hardest part for people. The real challenge was putting the community before yourself. That seems to have been the greatest difficulty, even historically.”—Jerry Grant

FM: At one point we said to Joan, “Would you like to get out and take a break?” And she said, “No, absolutely not.” She did not want to get out. Later, I realized the little lamp was shining right into her eyes for two hours. I said, “Joan, why didn’t you say something?” She said, “Oh, it didn’t bother me.” It made me realize there was really something there—she was so at ease in the cradle that it didn’t disturb her.

RS: I love that. For this current project, it was by happenstance that we landed on Los Angeles. The available space eventually guided us there. But it seems that staging this in Los Angeles could mean a lot in a year when the city has experienced so much, politically and socially. I’m interested to hear your thoughts on that.

FM: Well, it means something to me because my son and his girlfriend live there. They were both born in Paraguay, South America. She became an American citizen two weeks before the last election, and now she carries her passport back and forth to work in Downtown L.A. because she fears if she’s stopped, she might not be believed. I think that, along with the natural disasters of the past few years, there are few places in Los Angeles that allow people to congregate and find solace. To its credit, the Hauser & Wirth compound in Downtown L.A. is more than just an art gallery. There is an interest in people—in feeding people, gathering people—with chickens laying eggs, plants growing in the sunshine. It is a kind of community cauldron in a very urban area.

SB: Jerry, would the Shakers take anybody who said, “I want to join”?

JG: I think they would take anybody in at first. Then there was a period of discernment on both sides. You wouldn’t automatically be part of the community—you began with a probationary period, got trained and saw how it worked out. For many, it didn’t. They liked the concept, but daily life was too much. I think of Brother Arnold Hadd, one of the three living Shakers, who often says celibacy wasn’t the hardest part for people. The real challenge was putting the community before yourself. That seems to have been the greatest difficulty, even historically.

FM: American communities used to be more generous. I’ve always loved stories about the signs migrants would use, marking places along the way: “This is the house where they’ll give you bread.” “Here’s the doctor who will help without payment.” It wasn’t that long ago, really, but it certainly isn’t in practice now.

SB: Now there is this distinction between the deserving poor and the undeserving poor. That’s in total contrast to the Shakers, who cared for everybody. If someone needed food, they would feed them.

RS: And that same spirit carried into song. Can you talk about the music in “CRADLED”?

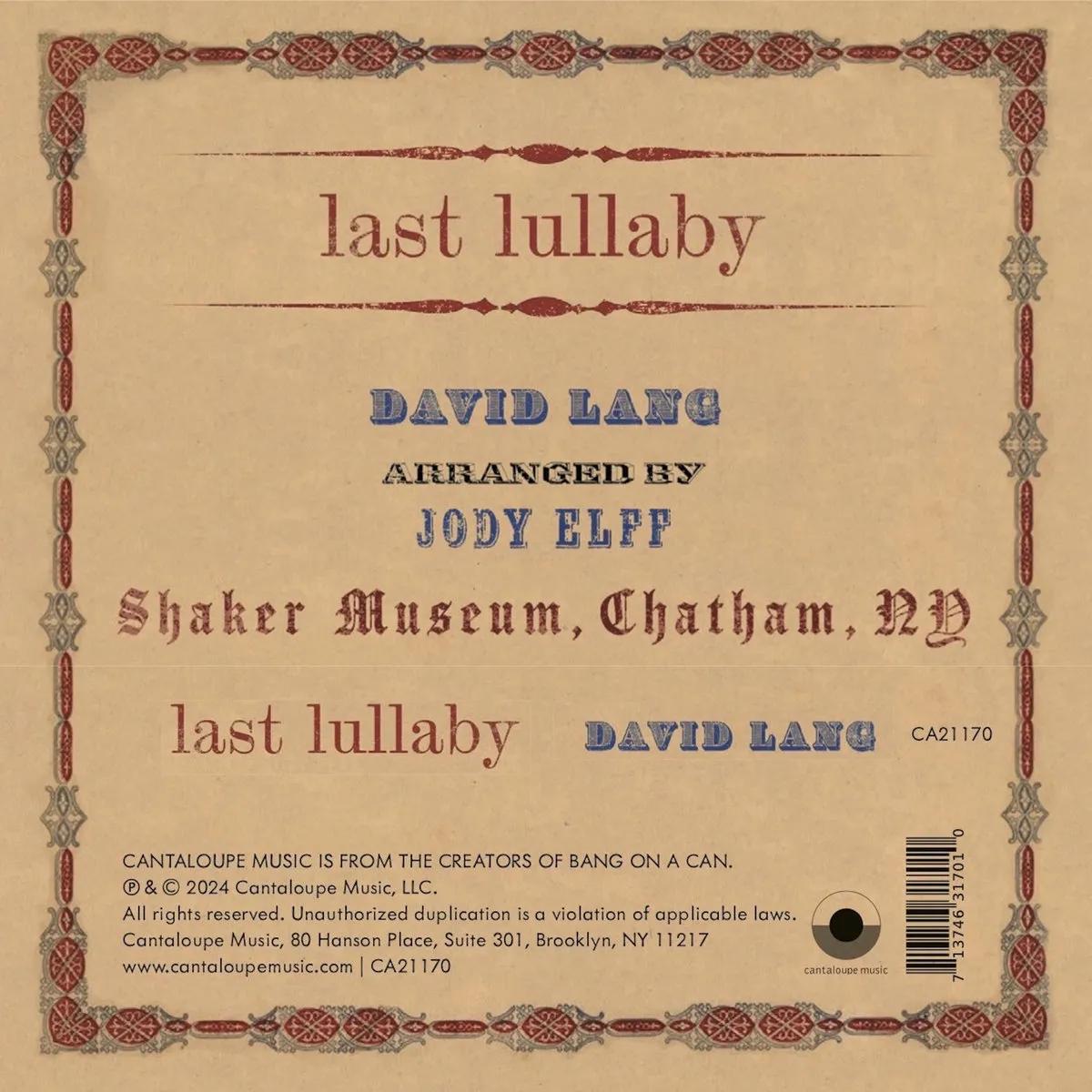

SB: Oh, yeah. The Shakers used music for so many things—working, but also as a way to bring the community together. But they didn’t have many babies, so they didn’t have many lullabies, per se. For “CRADLED” we worked with composer David Lang, who was interested in making an end-of-life lullaby. He adapted a traditional hymn about death called “O Brighter Than the Morning Star,” which is about eternal life, into a lullaby for death. And we also had a soundscape contributed by Skip Lievsay.

FM: It’s all so beautiful. Skip is someone I’ve worked with for years in film—he does sound design, and he created the ambient sound we were talking about. From the beginning, we knew we wanted a soundscape. At first, we imagined it simply as the ambient world of a Shaker community—perhaps what an elder in the cradle might have heard while convalescing—but with David, who has worked with Suzanne before, we expanded it even further. One of the things I really love is how, at the end of the composition, David talked about wanting it to repeat into eternity.

RS: It’s incredibly soothing.

SB: And it’s immersive—something you feel all around you.

RS: And their physical spaces were so distinctive. Jerry, could you talk about the peg rail? You see it everywhere in Shaker life.

FM: It should be everywhere, Russell![Laughter.] It drives me insane because I’ve been living in hotels for the last few months, and there’s never any place to put anything.

JG: I don’t know exactly where the peg rails came from, but Shakers adopted them very early. All of their meeting houses, beginning in 1785, had pegs. Over time, pegs became a standard part of Shaker architecture, and very few buildings lacked them. The Shakers hung everything a peg could hold—clothing, tools, brooms by the door—so things were both handy and orderly. It got items out of the way while making them visible. There was never a written rule that every building should have a peg rail all around it. It simply became their practice, an architectural detail that defined their spaces.

SB: Would a Shaker man have two pairs of pants, a few pairs? How much clothing are we talking about?

“American communities used to be more generous. I’ve always loved stories about the signs migrants would use, marking places along the way: ‘This is the house where they’ll give you bread.’ ‘Here’s the doctor who will help without payment.’ It wasn’t that long ago, really, but it certainly isn’t in practice now.”—Frances McDormand

JG: When you look at some of the clothing inventories, Shakers were quite well-dressed. They had work clothes and meeting clothes—probably more clothing than people in the outside world. They would say they bore the cross of celibacy, but they were not uncomfortable. They were well-fed, well-housed, well-clothed and well taken care of, medically. It wasn’t about denial of everything. As for storage, clothing would be in cases or drawers. And later on, by the 1830s, Shakers had closets in their rooms.

SB: That’s so interesting to me because I grew up Catholic and I think about how nuns, monks or priests take vows of celibacy. Many of the nuns I grew up with also took a vow of poverty, so they didn’t have a lot clothes. That’s a good reminder that the Shakers didn’t take a vow of poverty.

RS: Speaking of being well-fed, let’s talk about Shaker lemon pie.

FM: Yes! Number one, we all love pie. Everybody loves pie. I personally experienced this with a friend who, every summer would host a pig roast with a pie table—twenty-five pies. I remember the first time my son, maybe around eight, saw that table. His eyes were like, “Are you kidding me? I can have all that pie?” [Laughs.] I suggested for the original “CRADLED” opening party that we have a pie table. We didn’t have Shaker lemon pie, but we had apple pie and maple syrup jes’ pie.

SB: It was called jes’ pie? That pie was amazing.

FM: Right—jes’ pie, you know, meaning just pie made with eggs, sugar and butter.

JG: It’s what you would have in the middle of winter when you had no fruit.

FM: When you had no fruit but needed something sweet. But I’ll tell you what was really great—we invited people to the pie table before going into the exhibit room of “CRADLED,” and the experience of it all. I have to say, you don’t need alcohol to start a party. What you need is pie to start a party. [Laughter.]

RS: Jerry, is there any historical significance to the lemon pie? Or it was just something they made?

JG: Well, the Shakers would talk about getting shipments from New York City, New Orleans or another port—maybe a barrel of lemons or something similar. They came across odd foods from time to time. Of course, they weren’t growing lemons themselves, so it was likely considered exotic and lemon pie was probably a treat.

FM: Like the jes’ pie would be...

JG: The normal pie.

FM: Yeah. And in Los Angeles, Manuela restaurant is going to make us lemon pie.

RS: Yep.

FM: So good.

RS: It has been so great to talk with you all. Any closing thoughts before we wrap up?

SB: Sure. I think it’s important to note that all of this never would have happened if the Shaker Museum wasn’t concentrating on making a space for the archive to live.

FM: Right! It’s not an art gallery or a typical art museum. It’s an archival museum for the artifacts that are now being stored in beautiful barns in Old Chatham, New York, but need a new home. The ground has been broken, it’s happening, and that is what we are contributing to.

SB: When will the building be finished, Jerry?

JG: Construction started in August, and it’s about eighteen months of construction and then probably a year of moving in. Annabelle Selldorf, the architect, has designed the renovation of the building and an addition that goes onto it. I think we’re hoping that in the spring of 2028 we should be open.

RS: It’s also worth noting that she renovated the Los Angeles space where the show will be.

FM: Oh, that’s great. We need to tell her about the show.

SB: We should, yeah.

FM: We’ll rock her. [Laughter.] In the end, though, it really is about tending to one another, in all our days. That’s the truth we keep circling back to.

SB: The Shakers made it a way of life. “CRADLED” reminds us to carry that forward.

Listen to David Lang’s Last Lullaby on Bandcamp.com, where it is available to purchase as a digital album or limited-edition cassette

–

Photos: Vincent Tullo, taken at the Shaker Museum collections storage, Old Chatham, New York, 2025.

“CRADLED” is on view at Make Hauser & Wirth in Downtown Los Angeles through January 4, 2026 (weekends only). The exhibition features cradles on loan from Canterbury Shaker Village, New Hampshire; Fruitlands Museum, Massachusetts; Hancock Shaker Village, Massachusetts, and South Union Shaker Village, Kentucky.

Last Lullaby was composed by David Lang to accompany the installation CRADLED. Adapted from the traditional hymn O Brighter Than the Morning Star, a rumination on eternal life, the piece is a haunting lullaby sung by Katie Geissinger that gradually seems to fade behind the veil of encroaching death—a subtle and inevitable transformation that engineer and producer Jody Elff enhances with vivid, vintage sound effects. It is available to listen online here, where it can be purchased as a digital album or limited-edition cassette.

–

Suzanne Bocanegra is an artist in New York. Her most recent performance, Honor, an Artist Lecture by Suzanne Bocanegra Starring Lili Taylor, was commissioned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and traveled to institutions including LA MOCA, ICA Boston, the Walker Art Center and NYU Skirball.

Jerry V. Grant has been the director of library and collections at the Shaker Museum since 1987. He holds an undergraduate degree from Michigan State University and an M.L.S. from SUNY Albany. Grant has written and contributed to books that include Shaker Furniture Makers and Shaker: Function—Purity—Perfection.

Frances McDormand holds a New York State driver’s license. Lots of work. Lots of awards. Lots of fun. Lots of mussels.

Russell Salmon is director of public programming at Hauser & Wirth as well as an independent curator and a seasoned performer, producer and director.