Conversations

Poetry in Space

Contemporary curators on the legacy of Swiss art-world impresario Harald Szeemann

Szeemann at the opening of Documenta 5, Kassel, West Germany, 1972. Courtesy Kassel documenta Stadt. Photo: Carl Eberth

Harald Szeemann, who died twenty years ago this year, profoundly shaped a generation’s understanding of contemporary art. He gave people a reason to care and to fight about it, and many entered the art world because of his work. From the time of his landmark “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form” at the Kunsthalle Bern in 1969, whose stellar cast of artists included Joseph Beuys, Walter De Maria, Michael Heizer, Bruce Nauman, Eva Hesse and Richard Serra, he gave the exhibition as a format a starring role in the social upheavals of the 1960s. Amid the fallout from what was widely seen as a frontal attack on the idea and value of the art institution itself, he resigned and founded the Agency for Spiritual Guest Labor—a curatorial agency long before a word for such a thing existed. Szeemann’s Documenta 5, in 1972, was the original “100-day event”—a sprawling cartography of current developments under the title “Questioning Reality: Image Worlds Today.” It established a new benchmark for Documenta as an institution, notwithstanding the objections of several artists who felt that their intentions had been steamrolled in favor of the show’s curatorial themes. From then on, the curator—or “exhibition-maker,” as Szeemann more commonly described himself—entered the stage of art in a new way. This development would, for better or for worse, heavily influence the course of not only exhibition-making but also art-making for the rest of the long 20th century and into the present.

Szeemann’s first exhibition after Documenta was a straight-up refusal of the customary deformation professionelle of contemporary art insiderhood: “Grandfather: A Pioneer like Us” (1974), an apartment exhibition made up entirely of items owned by his grandfather Étienne Szeemann, a famed hairstylist who had set up shop in Bern in 1904. In later years, the lodestars of the 150-plus exhibitions Szeemann organized—which would come to include two Venice Biennales—were two key ideas: “individual mythologies” and the “museum of obsessions.” Both of these deeply unscientific categories encouraged an openness to outsiders and strengthened Szeemann’s resolve to organize exhibitions with “intensity” as the primary yardstick of quality. It was always a tall order, but his charisma and curiosity helped; his ambition and motivation, too. In an epic trilogy of traveling exhibitions spanning from 1975 to 1984—"Bachelor Machines,” “Monte Verità” and “Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk” (The Tendency Toward the Total Work of Art)—he de-centered the narrative of modernism to embrace anarchism, Lebensreform, psychoanalysis, art brut and more. The first of these shows put Marcel Duchamp into dialogue with the writer Alfred Jarry and the healer Emma Kunz, among many others, while the second focused on the early 20th-century artists, anarchists, fantasists, theosophists and proto-hippies who experimented with new ways of living on Switzerland’s Mountain of Truth (Monte Verità) near Ascona. The third exhibition traced the idea of the synthesis of life and all art forms in a total work of art, from Wagner and Ludwig II to Antoni Gaudí. One theme of all three shows was the tension between desire and its fulfillment.

Before becoming the director of Kunsthalle Bern in 1961 at just twenty-eight-years old, Szeemann had produced one-man theater works—as actor, playwright, set designer and painter. And in many ways, he never left the stage, even when he was mounting exhibitions that pushed art to be weirder, more wonderful and more attention-grabbing than the gatekeepers of the ivory tower allowed. His blind spots (among them far too little engagement with art made by women), his enthusiasm for esoteric visionaries, his idealistic personality and his romantic grandiloquence were often hard for the self-serious American establishment to swallow, not least in the years after Benjamin Buchloh’s withering attack on Joseph Beuys in 1980. Szeemann, in fact, hardly organized exhibitions in the United States. But the 20th century is now really over. And the paper trail of Szeemann’s research—thousands of artist files, photographs and books—has found a permanent home in Los Angeles at the Getty, where it is the largest archive ever to enter its collection.

Today’s art world—unevenly globalized, spectacularized, increasingly under attack and in many respects suddenly unsure of the justifications for its former aplomb—might well be reinvigorated by returning to the utopian horizon of curating’s potential that Szeemann bequeathed us under the aegis of his exhilarant motto “to stage is to love.”

—Alexander Scrimgeour

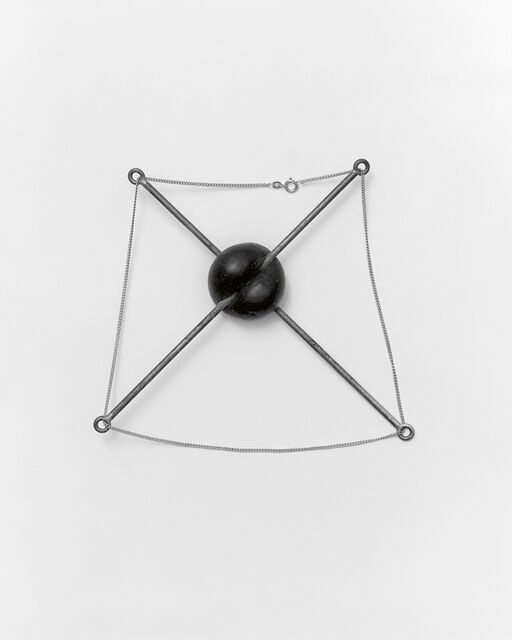

Two enigmatic objects from Szeemann’s archive from Pretenzione Intenzione: Objects of Beauty and Bewilderment from the Archive of Harald Szeemann, edited by Michele Robecchi, Bohdan Stehlik, and Una Szeemann, with Elsa Himmer (Edition Patrick Frey, 2025). Photos: Bohdan Stehlik

Johanna Burton:

In the way that one might trace today’s unthinkable political moment back to a particular inception in the figure of Ronald Reagan, one can follow a red thread linking the current (arguably outdated, yet persistent) profile of “the contemporary curator” undeniably to the figure of Harald Szeemann. The comparison is an exercise in imagining how eras, ways of thinking, even zeitgeists, assume embodied and enduring form—in iconic figures who stand for their time, or the one just ahead of them.

Szeemann’s practice—that of a kind of curator recognizable to us because his version was so radically at odds with previous definitions—continues to beckon to those entering the field or looking for new hope within it. Like the contemporary museum, the incredible legacy of Szeemann is both a reminder that orthodoxies can be shattered and new platforms created and a testament that not many ever are. Szeemann’s radicality was not the last, but the model that he ushered in still eclipses most others and is carried on, in large part, through iterations indebted to him.

His curatorial persona did more than center his ego (though it did that too). It animated the space between objects and artists as a place to coproduce meaning, to rewrite history. While so often associated with Conceptual art, Szeemann was as much a feelings man, so bold as to articulate the affective, the spiritual, even the mystical as tools to be deployed with sincerity—and with abandon. It didn’t hurt that he was magnetic, described (and self-described) with words like shaman, meant to evoke the alchemical and the otherworldly, even if the shows themselves were often populated by works ostensibly at odds with such baroque ways of thinking.

Of course, this is what continues to be so dazzling about many of the literally hundreds of projects he manifested, too—blatant manipulations of individual objects (and individuals themselves) into impermanent constellations, like known words put together into sentences that suddenly read as a foreign language. As Szeemann famously articulated the climax of such juxtapositions: “To stage is to love.” Much has been made of his history in the theater and his way of articulating art exhibitions not as passive presentations of things but as unfolding events. His disregard for any generally accepted context for artworks allowed him to write new narratives and to insist that the agency to make such materialist editorial decisions was there for the taking.

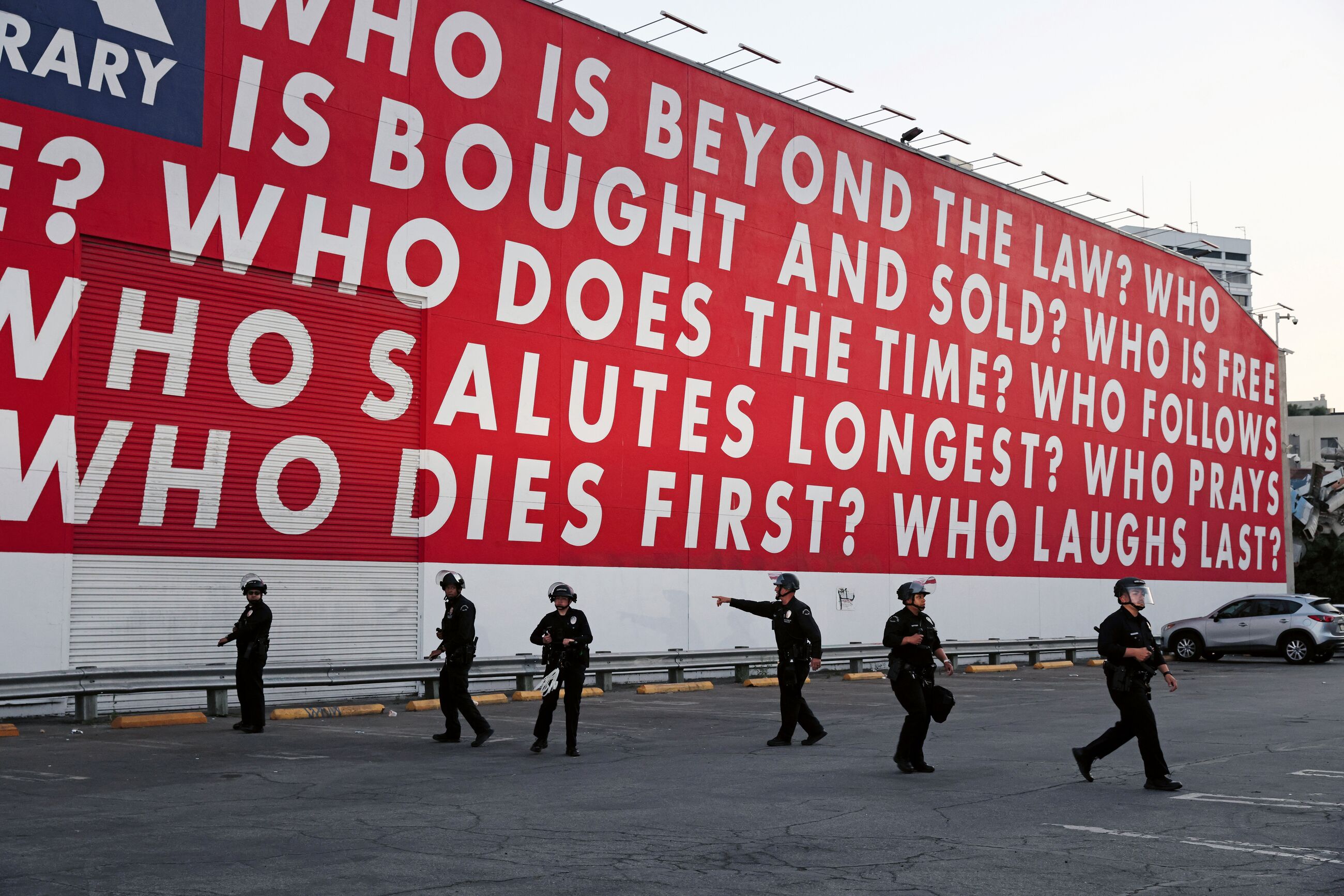

I write these words in the middle of June in Los Angeles, where I’ve lived for the past four years. Last weekend, the National Guard was deployed against public protests that had not yet come to pass but were being described by Trump preemptively as out of control. The epicenter was (and continues to be, some days later) directly across the street from the downtown facility of MOCA, whose large facade is adorned with Barbara Kruger’s 1989 Untitled (Questions). The mural, and its words (“WHO IS BEYOND THE LAW?” WHO IS BOUGHT AND SOLD?” “WHO IS FREE TO CHOOSE?”) became the backdrop for endless and endlessly circulated documentation of the protests and clashes with law enforcement. Intentionally, and not, Kruger’s mural has become synonymous with these events (as it has been in previous years, during other protests). Her iconic work, now nearly forty years old, seems timelier than ever—or, perhaps its longevity signals an invitation we can only now begin to understand. Kruger maintains that her ultimate hope for her work is that it becomes irrelevant. Until then, the museum must remain a crucial space to test theories, to suspend oppressions, to stage possibilities.

Szeemann’s own models might be understood as designed at least in part to suggest that there were always more to come, to be discovered and deployed. “In order to entertain certain ideas,” he wrote, “we may be obliged to abandon others upon which we have come to depend.”

If ever there were a time to abandon, without abandoning hope. . .

LAPD officers beneath a muralby Barbara Kruger during ademonstration against ICE raids,Los Angeles, 2025 © Gabrielle Lurie and San Francisco Chronicle; San Jose Mercury News Out; East Bay Times Out; Marin Independent Journal Out; San Francisco Examiner Out. Photo: Gabrielle Lurie

Ingrid Schaffner:

Harald Szeemann died twenty years ago, but his work lives on in Los Angeles, where the Getty Research Institute is home to the nearly half a linear mile of material that constitutes his archives and papers. What better place to spend a day actively reflecting on the legacy of the great Swiss curator?

Upon my arrival in Special Collections, a trolley, loaded with boxes and my name on it, stood parked and ready. One should always get one’s bearings before embarking on a search, and my feminist compass pointed in the direction of all files labeled “Lucy Lippard.” Like a needle in the haystack of papers related to “When Attitudes Become Form,” one of these contained Szeemann’s invitation to his American peer to write the introduction for his 1969 exhibition of the “new art” that they both championed as curators. Evidently, Lippard declined. She did, however, reply vehemently to an obnoxious letter in which Szeemann seemingly defended the lack of women artists in Documenta 5 in 1972. The letter turned out to be a provocation cooked up by members of the Guerrilla Art Action Group, which worked to root out art world injustices.

Szeemann later penned a short apology to Lippard for the words he did not write. He also kept in his curator files a Bard CCS announcement for a 1995 exhibition, curated by Neery Melkonian, “Sniper’s Nest: The Art That Has Lived with Lucy R. Lippard,” which features a portrait of Lippard seated amidst her archives.

Following my own predilections, I next went to the files for “Jason Rhoades,” an artist with whom Szeemann and I both worked as curators. The three-page handwritten list of materials for Rhoades’s sculpture in the 1997 exhibition “Epicenter Ljubljana” included a donut machine, piles of donuts and “donuts that didn’t make it.” A vernacular archive in its own right, the list was also a record of the kind of wickedly imaginative world builders, generators of chaos and creative outliers that Szeemann championed—and was himself.

The search for “cars” led me to a small poster advertising automobile paint, beautifully illustrated with a devil with a brush. One box contained Edward Kienholz’s documentation binder for Five Card Stud, his life-size tableau of white men preparing to castrate a Black man within a circle of vehicles. The binder is inscribed “with great admiration” to Szeemann for including this horrifying indictment of American racism in Documenta 5. The “cars” category also yielded the largest box on the trolley. A veritable archival construction, it was customized inside with compartmentalized trays full of toy cars, each one carefully wrapped in acid-free paper. According to a note in the finding aid, this collection was Szeemann’s research material for “Automobility,” an unrealized exhibition project.

“Cheese,” my final archive quest, inspired by Dieter Roth’s legendary Los Angeles 1970 exhibition “Staple Cheese (A Race),” likewise remains unrealized. To see the cheese grater that appeared in “Grandfather: A Pioneer like Us”—the 1974 apartment exhibition that Szeemann dedicated to the life and work of his grandfather, a famed inventor and hair stylist—I would have to return another day. And I shall.

The making of Michael Heizer’s Berne Depression at Kunsthalle Bern before the opening of “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form,” 1969 © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Photo: Balthasar Burkhard

Robert Storr:

I had the good fortune to know Harald Szeemann pretty well as an elder statesman “exhibition-maker”—as he preferred to be called—during my years at the Museum of Modern Art (2001–12) and thereafter. I also worked with him in some capacity on a number of projects, among them the 2007 Biennale of Sydney and the 2005 Moscow Biennale, when we visited Lenin’s tomb together. He consulted with me on the Bruce Nauman retrospective that concluded its American run at MoMA in 1995 and at his behest moved on to an extra stop in Zurich. As members of the jury for the Holocaust memorial in Vienna, we both played pivotal roles in the selection of Rachel Whiteread, and we had to work to protect our choice from political sabotage by her opponents.

In short, I was exposed to Harry as a cultural dealmaker in several key situations, and I have never encountered a shrewder or more adroit art politician. He was certainly no saint. As in Vienna, for example, when he went up against a stubbornly old-school Simon Wiesenthal, who had a friend and fellow Holocaust survivor in the competition, whom he adamantly supported. Wiesenthal eventually yielded to Harry’s advocacy after Harry, affecting a strong Yiddish accent, stressed the biblical themes in Whiteread’s work and pronounced her name “Rakhel.” As Harry (and Wiesenthal) knew full well, Whiteread wasn’t Jewish, but she was the superior candidate.

One must never forget that Harry started out in the theater world, and to say that he was a showman includes an appreciation of The Big Gesture as a path to results that art history and art theory cannot always be relied upon to deliver.

The hagiographic embrace of his career by younger Savonarola-like Po-Mo curators who came after him or grew in his shadow without the same flair or ruthlessness is puzzling to me. But Harry served art well, on the whole, and set an example that is unlikely to be rivaled anytime soon. I enjoyed his company and think he appreciated mine.

Installation view of Szeemann’s 1974 exhibition “Grandfather: A Pioneer like Us,” restaged at Swiss Institute, New York, 2019. Courtesy Swiss Insitute. Photo: Daniel Pérez

Zoé Whitley:

I should come clean from the outset. While Harald Szeemann is one of the most storied names in the field of curating, I never physically experienced one of his exhibitions. (I started curating two years prior to his death.)

Szeemann’s life appears to have been structured to accommodate a pure and near-total devotion to his craft. He actively engaged in making a future art history, building artist communities through a lifelong marriage of conviction and conceptualism. I know that his dialogues with artists were sacrosanct to him, whether they were in person or through correspondence. Szeemann showed his audiences that the best work is nearly always the least reproducible, which feels important to remember in the age of Instagram and TikTok. It was, in fact, a written description of a Szeemann-curated La Monte Young performance that led me to seek out Young and Marian Zazeela’s ongoing Dream House in New York City. I couldn’t comprehend what was being described but I was tantalized. One can still go and lie on the floor of Young and Zazeela’s loft, as I did, to take in their powerful work in sound and light. Credit where it’s due for exhibition-making as embodied experience!

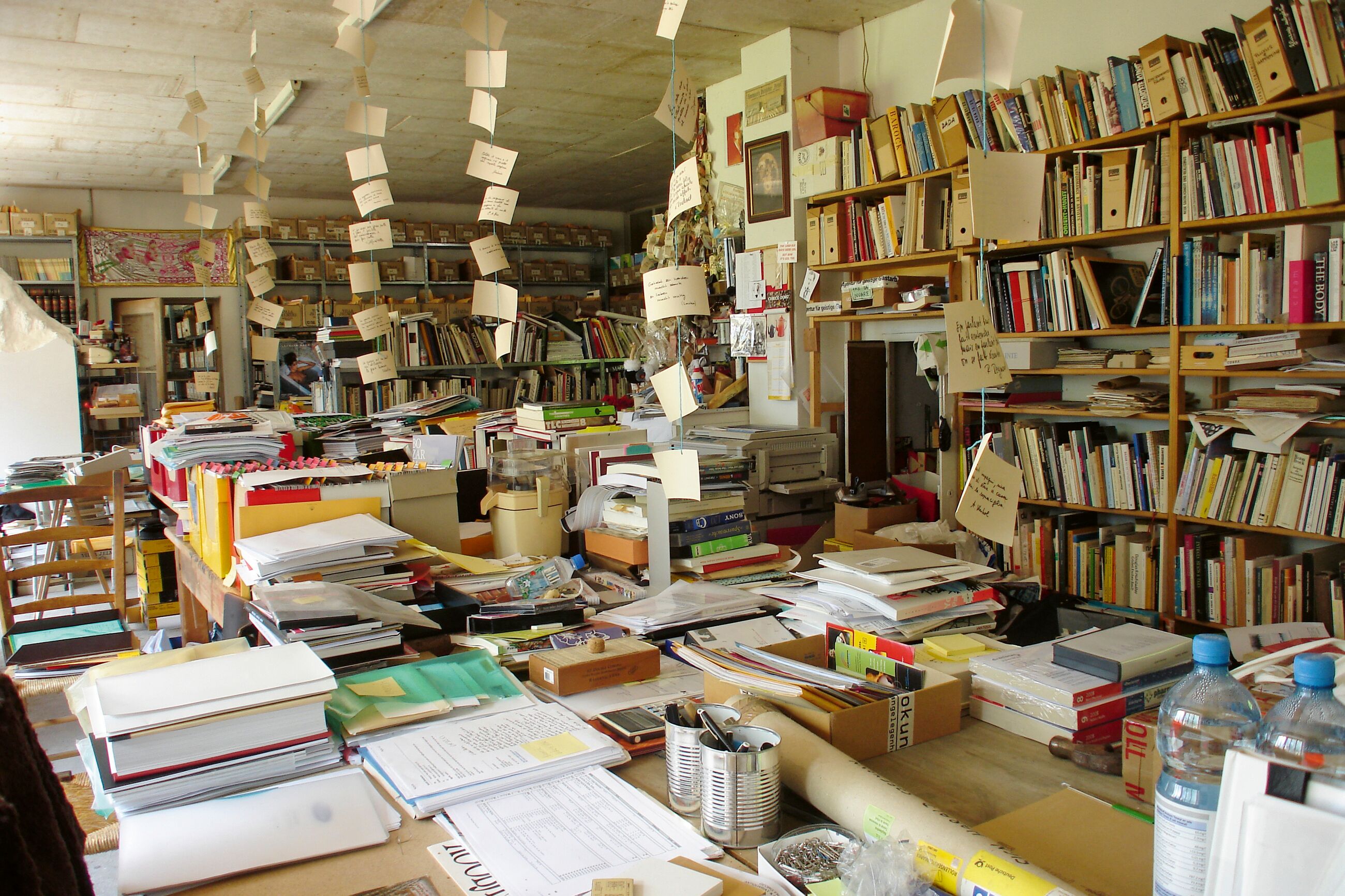

Having established his Agency for Spiritual Guest Labor, Szeemann cultivated a role as an insider/outsider and made space for unconventional artists’ practices (in music, performance and various other forms of time-based media, to say nothing of visionary artists who worked well beyond the status quo). Such artistic freedom came at a cost. The “insider” aspect of his equation was crucial: Szeemann was a one of one, internationally in demand and financially well supported. From his Fabbrica Rosa (Pink Factory) in Ticino, Switzerland, a labyrinth of books and ideas, he weaved in and out of institutions, unfettered by the quotidian constraints of org charts, policy rewrites and broken systems.

I ask myself: Who gets to follow in Szeemann’s uncompromising footsteps now and what modifications are required? Freedom of movement, for one, was a precondition of his achievements. Certain passports unlock gates, allowing one to be nearly everywhere, to see virtually every show. Curator as perpetual migrant is theoretically compelling but practically complicated (pro tip: Don’t be an actual migrant). How do those obstacles get addressed? The late curator Bisi Silva (1962–2019) created the Àsìkò Art School, which moved across Africa from Lagos to Accra, Dakar, Maputo and Addis. Bisi recognized that most aspiring artists and curators didn’t have a Pan-African network for in-person dialogue and constructive critical friendship, due to visa restrictions and the additional absurd reality that even people with the means and ability to visit neighboring countries often had to do so along routes that detoured through European hubs. Curating today isn’t only about exhibition-making. It is about community. And the roots of this vital idea wrap back around to Szeemann and his ideals of connection, convening, corresponding and conviviality.

I believe he would want us not only to continue expanding the range of the artistic expressions that inform our views but also to examine the circumstances in which we are able to curate and to poke resolutely at preconceived hagiographies. That shouldn’t stop us from trying to reinvent what is and reimagine what can be, to make exhibitions and maybe in the process to reshape their surrounding contexts.

Àsìkò Art School, Dakar, Senegal, with Bisi Silva (right), 2014. Photo: Erin Rice

iLiana Fokianaki:

It’s impossible to be director of Kunsthalle Bern without thinking about Harald Szeemann. Although it’s been almost sixty years since he resigned his directorship, his name still pops up the instant Kunsthalle Bern is mentioned. My first exhibition as its director was a solo show by the Ghanaian-born artist Ibrahim Mahama, who wrapped the kunsthalle in dialogue with its 1968 wrapping by Jeanne-Claude and Christo during Szeemann’s tenure. In preparation for the show, I began reading Szeemann’s correspondence with artists. It shows his unparalleled dedication to groundbreaking projects, as well as his tenacity and resilience in overcoming constant obstacles. I was impressed and grateful to get this insight into his work. Like many curators of my generation, I knew about his groundbreaking exhibitions, but I now have a better understanding of the person behind them.

In many ways, Szeemann’s exhibitions, his writing and research, his “artist discoveries” and his other accomplishments are extensively documented and well known. Likewise the controversies about his artistic choices and the lack of women artists in his exhibitions. What is much less discussed is that, already as a twenty-eight-year-old director in Bern, he had a very clear idea about what art could and should be doing. He stayed admirably loyal to that idea, uninterested in satisfying the demands of political correctness or following trends. He dealt with conservativism—both as the director of an institution and later as an independent curator—by firmly standing his ground. There is a lot to learn from him, especially since our profession is grappling with the re-emergence of conservativism today. Furthermore, Szeemann allowed room for critique from the artists he worked with, not only toward the institution (as both a space and a concept) but also toward the curator as a figure of power.

It is thanks to Szeemann that we still today understand the curator as an auteur, an active agent, one who creates narratives, explores ideas and discusses the world we live in through his or her research and interests. His own practice as an exhibition-maker shows not only that curators can be eccentric, at times even difficult creatures, but also that they are interdependent and interconnected with artists, ideas, books, music, theater, science, mysticism and all kinds of wonders. Szeemann demonstrated how (and why) a curator could or, better, should be invested in such wonders, using them to weave concepts and stories. In his own words, he always “complied with the need to employ the exhibition medium for the visualization of a myth.”

Entrance tickets for Szeemann’s “Monte Verità” exhibition, 1978. Photo: Sara Dolfi Agostini

Bice Curiger:

When I showed four women (Janine Antoni, Sadie Benning, Sophie Calle and Sylvie Fleury) and four men (Julio Galán, Gabriel Orozco, Raymond Pettibon and Ugo Rondinone) in my first large exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zürich in 1994, one of my intentions was to make a statement directed at Harald Szeemann.

I had been glad to start work at the kunsthaus in the position of “permanent independent curator”—which is to say, to take on the role originally designed for Szeemann personally, a role that enabled him to organize outstanding exhibitions there for twenty years. As much as I marveled at Harry and was—as I still am—grateful for all that I was able to learn from him early on, it had also become increasingly apparent where his Achilles’ heel might be.

Alongside “Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk” (The Tendency Toward the Total Work of Art), his sensational show that occupied the vast columnless exhibition space of the kunsthaus in 1983, Szeemann had mounted impressive monographic presentations of the great male artists of the time: Jörg Immendorf, Sigmar Polke, Mario Merz, Cy Twombly, Richard Serra, Georg Baselitz, Walter De Maria and Bruce Nauman.

The year I started at the kunsthaus, I wanted to organize a Cindy Sherman midcareer survey in the large gallery, where only one woman had previously been granted a solo exhibition (Germaine Richier, in 1956). Cindy was forty-one at the time. But when I proposed it to the exhibition committee, Szeemann was adamantly opposed. A comprehensive solo show, curated by Martin Schwander, took place soon afterward at the Kunstmuseum Luzern.

I learned from Harry how disparate works can communicate with one another in utterly surprising ways. He also showed how museums, kunsthalles and galleries can operate beyond the art world proper, reflecting on and contributing to broader political and cultural shifts. But terms like “individual mythologies” and “museum of obsessions”—which became part of the lore (or the marketing) of his curatorial work—left me cold.

My differences with Harry were surely generational as well. I’m fifteen years younger, and for me the 1960s and ’70s were largely shaped by pop and counterculture, important frames of reference that he lacked. At the same time, there is no doubt that his 1978 exhibition dedicated to the history of Monte Verità was an outstanding accomplishment in recovering and communicating the legacy of an early utopian artistic community.

In Switzerland, another important mentor for my generation was already on the scene by the 1970s: Jean-Christophe Ammann, who had been Szeemann’s assistant at Kunsthalle Bern in the 1960s and was part of his team for Documenta 5. From 1968 to 1977, Ammann was director of the Kunstmuseum Luzern and from 1978 to 1988 of Kunsthalle Basel. While Harry sought seclusion in Ticino after Documenta in order to prepare his important exhibitions embedded in the history of ideas, Jean-Christophe showed Gilbert & George in Lucerne in 1972. In 1974 he presented “Transformer,” one of the earliest exhibitions anywhere to focus on the category of gender. At the Kunsthalle Basel his shows included an all-women exhibition with Miriam Cahn, Hannah Villiger, Vivian Suter and Rut Himmelsbach in 1981 and a group show with the photographers Peter Hujar, Larry Clark and Robert Mapplethorpe in 1982. Over the subsequent decades, it was Ammann who stood out as the communicative, sociable and generous older colleague who again and again managed to do things that served as an inspiration to a younger, postmodern generation.

Another thing to add: When the prewar generation temporarily opened the valve of a pent-up sexuality, it was sometimes too much for us—in Szeemann’s work, it came swathed in Duchampian smoke and mirrors. I await the day when someone offers a feminist take on the Bachelor Machine that manages not to truck with men’s overweening sense of their own profundity. It was no coincidence that Meret Oppenheim—one of the few women in Szeemann’s 1975 “Bachelor Machines” exhibition—sent Harry a friendly but firm letter protesting against her inclusion in a section called, of all things, “Femme Fatale.” Once again, a man had reduced her to a Surrealist muse and (as she carefully explained) disregarded the systemic conditions of her existence as a female artist.

View of the interior of the Fabbrica Rosa, Szeemann’s studio and office space in Ticino, Switzerland. Photo: Aufdi Aufdermauer

Christian Rattemeyer:

In February of 1997, I spent a week in Maggia, Switzerland, working in Harald Szeemann’s sprawling office, which he called the Fabbrica Rosa, to review his archive of his landmark 1969 exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form.” At the time, Harald was working on his archives while also finishing up the 1997 Lyon Biennale and fielding offers for other biennials and exhibitions. He usually arrived around noon and worked straight through 8 p.m. with no lunch break. The office was unheated and bitterly cold in February, which only added to my pangs of hunger, as I usually arrived by 10 a.m. without a good breakfast to prepare me.

I had met Szeemann occasionally when I was young, as he had been friendly with my father, who also worked in the art world. But I remember this later visit not just as my first professional encounter with Szeemann but also as the fortuitous moment when my interest in his work from the 1960s overlapped with my experience of his exhibitions in the 1990s. At the time, what interested me was the visionary curatorial work of Szeemann’s Kunsthalle Bern years—the early invitation to Christo to “wrap” the building, and, of course, “When Attitudes Become Form,” which led to his departure from the kunsthalle and initiated his career as a freelance curator. I felt more distant from his arguably more important series of monumental thematic group exhibitions organized in the 1970s and early ’80s—from “Happening & Fluxus” in 1970 and Documenta 5 in 1972 to his investigations of the early 20th-century countercultural communities of Monte Verità and the conclusion of this research in the ambitious exhibition “Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk.” It was as if the underlying utopian desire of a life like Szeemann’s, to live wholly according to drives, had, by the mid-1990s, become not just historical but impossible to imagine.

But seeing Szeemann’s exhibitions at the time of my research allowed me to understand how great exhibitions can mold curatorial intention into visceral experience—a spatialized, bodily argument. In 1991, he staged the first of several exhibitions engaging with a national psyche, as it were. Naturally, he began with his home country. “Visionary Switzerland” (1991) not only told the story of Swiss art—from Nicholas of Cusa’s visit to the 1430 Council of Basel all the way to Meret Oppenheim—but also captured its overall weirdness: Swiss art was strange, wild, untamed and constantly blurring the lines between self-taught and academic, eccentric and famous. Szeemann’s 1993 Joseph Beuys survey for the Kunsthaus Zürich, the first retrospective after Beuys’s death, remains a profound experience for me. It repudiated the argument that Beuys’s installations could never be moved, replicated or reinstalled without losing the unique charge he instilled in them. The exhibition also re-situated Beuys as a sculptor who had learned important lessons from 1960s post-Minimalism and downplayed his reputation as a German mystic. And Szeemann’s 1999 Venice Biennale, which for the first time used the entire Arsenale as an exhibition space, created the infrastructure for an ever growing, ever more global version of the event and initiated the decade of global biennial fever that reached its apex somewhere around 2011.

Szeemann’s exhibitions of the 1990s set an example. They were the mature work of a master of his craft. For a young viewer and aspiring curator, these creations—whether personal retrospective, thematic group show or global biennial—were master classes. For the art world, they remain classics.

Installation view of Bruno Weber’s Weinrebenpark (Vineyard Park), 1962, in a model by Peter Bissegger in “Visionary Switzerland,” Kunsthaus Zürich, 1992. Courtesy Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Graphische Sammlung und Fotoarchiv. Photo: Verena Eggmann

Carol Yinghua Lu:

When I first started working in the art world, I was often reminded by my mentor to consider the giants who preceded me as colleagues, not as heroes impossible to emulate. This notion, a collegiality based not on the primacy of power positions but on work and shared intentions, is one that I think Harald Szeemann would likely endorse.

Szeemann, who became synonymous with the advent of globalism in contemporary art, never curated an exhibition in China. He visited China in search of artists for his Venice Biennale in 1999 and sat on a jury for an award for Chinese artists. That was pretty much the extent of his artistic engagement with China. Nevertheless, I have found heartening resonance in the legacy he left behind. In 2010, I co-curated an exhibition titled “Little Movements: Self-Practice in Contemporary Art” with the artist and curator Liu Ding. In the face of the growing three-headed beast—spectacle, power and capital—that is now the dominant experience in global contemporary art, we wanted to foreground not art as such but acts of curating, institution-building, publishing and research as creative practices coequal with art-making. Then and since, we see the true relevance of art as something determined not simply by external factors but also by creative intentions, imaginative power and intensity.

In the 1960s, Szeemann invented exhibitions as expressive mediums and placed “individual mythologies” at the heart of his methodology. He prized artists above all and saw his relationship with them as a “going-together.” He defined the role of the independent curator as one free of all constraints, not only those of the art institution but also those of the social institution as a whole. His independence went so far that he essentially established himself as a one-man institution, his mission rooted deeply in a sense of the value of intellectual processes and creative vigor over institutional convention. He pursued this mission at the risk of offending existing orders and even at the cost of his own job.

In Szeemann’s 1972 Documenta, Joseph Beuys chose the medium of the office to make the point that creativity can flourish anywhere. Likewise, Szeemann’s model insisted that a curator can be creative anywhere. Even as big international exhibitions came to be seen, around the turn of millennium, as a disease threatening the art world, he advocated for an increase in the number of biennials. “Everything depends on the curator,” he said. He saw the curator as a creator as well as a force that makes creativity possible.

Since Szeemann’s passing, curating has lost much of its agency. Hobbled by institutional bureaucracy, funding requirements, popular demands and superficial themes, it has become ever more removed both from art and from reality. The situation makes me all the more grateful for the precedent set by Szeemann, as a colleague. He associated curating with intuition, perceptiveness, creativity, adventure, obsession, responsibility and possibility, regardless of the conditions around him. He opened doors that, regardless of the conditions around us now, will remain open.

Szeemann in 2001. Photo: Aufdi Aufdermauer

–

Johanna Burton is the incoming director of the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia and was previously director of MOCA, Los Angeles.

Bice Curiger is a Swiss art historian, curator, critic and publisher.

iLiana Fokianaki is director of Kunsthalle Bern.

Carol Yinghua Lu is an art historian and curator who lives and works in Beijing.

Christian Rattemeyer is a curator and writer, and the director of Arts&Rec, an artist residency program in upstate New York.

Ingrid Schaffner is curatorial senior director at Hauser & Wirth.

Robert Storr is a curator, critic, painter and writer based in New York.

Zoé Whitley is an art historian and curator based in London.

–

The anonymous items from Szeemann’s archive featured in Pretenzione Intenzione, of which two are illustrated above, were shown an exhibition in Monte Verità, Ascona, Switzerland, this past summer. Learn more about the publication and the writers paired with objects within it.