Fiction

(Maybe Prologue)

By Margaux Williamson

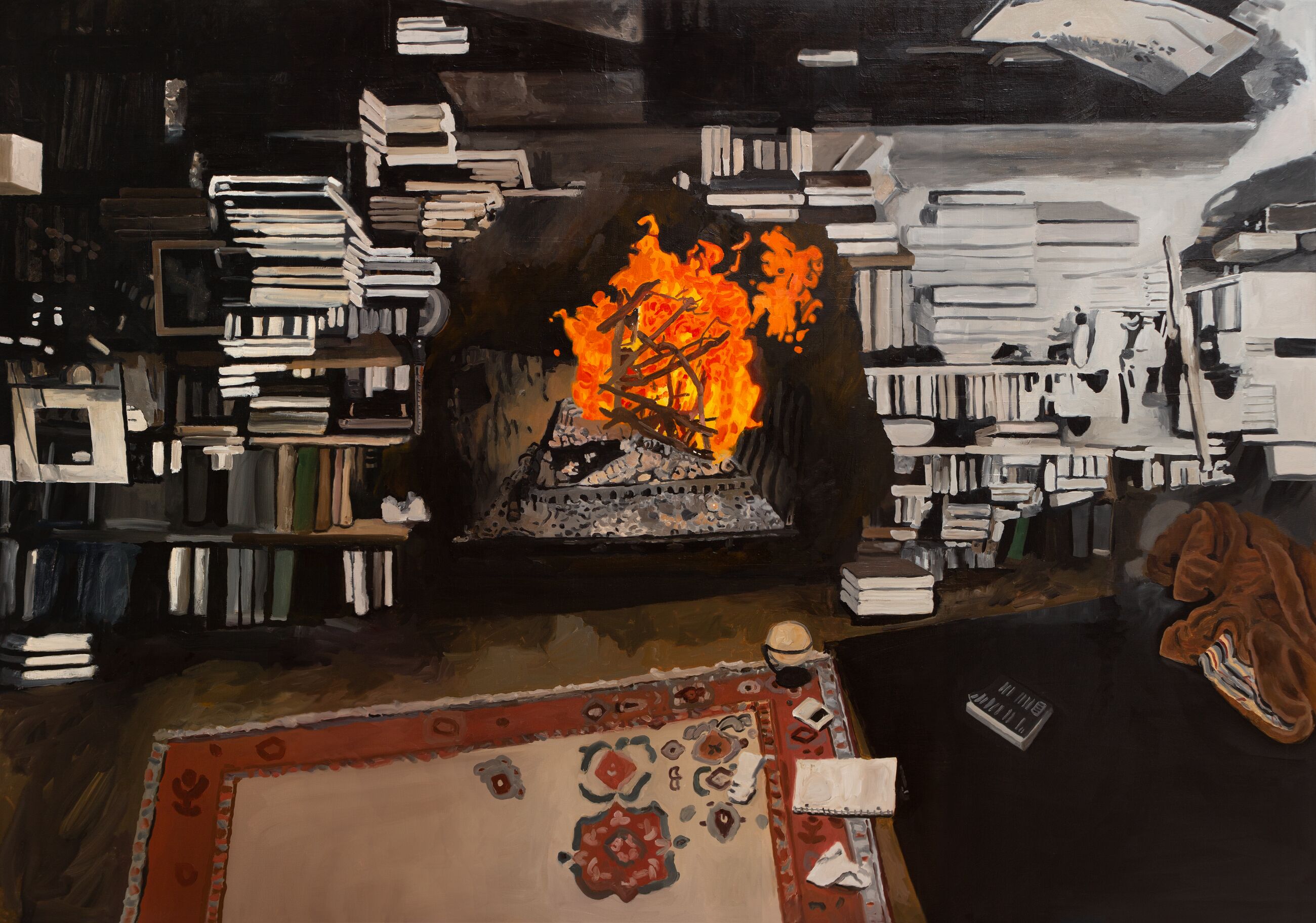

Margaux Williamson, Fire and Books, 2022

My illness coincided with the war so I just lay there. For months or years looking out at the confines of my room, seeing nothing, my eyes adjusting to the dark, time moving slower the closer I got to the ground.

It is not the first war I’ve slept through, which makes me feel a little uneasy and responsible. I don’t mention this to anyone, as it suggests I am in control which, I could see, would seem sad. “I did this,” I would say, my hair falling out, my body swollen and sore, the drugs for the drugs and for those drugs in a program of mild neuron death. Even if I said it I would get the words wrong. I would say, “I park here,” and people would nod. It takes all my strength to say hospital instead of mall, chemo instead of candy, visions instead of visitors. Someday I might not get back up again, but I doubt it. I think I’ll always have to get back up again.

But it’s wonderful to lie down! Not to be expected to stand up! Not to be expected to open the door or go to a party. There are those who still come to see me or who write to me, one by one, somehow never running into each other, like a machine that runs on magic, warming the room up just at the coldest and darkest moments. Or maybe it only seems to run well, as none of them come so often.

(Notes on the ones who come)

One is rare.

One is unique and is part of the National Health Program.

One comes from the place where the Abrahamic religions split off.

One is new without tags.

One comes from a visual development kit.

One comes from God.

One works for God.

One is a Pom.

One is from the old New York gold shop.

••

Two connections are about the soul.

One connection is also about the soul but is called God Heals.

One connection is about the future.

One connection is about a book.

One connection is of the earth soul, not the spirit soul.

One is the most volatile kind of connection.

One has envy that is not great.

One connection is about the Great Barrier Reef.

••

Sarah is Nordic and says I am like Anoushka, the goddess of blindness.

Or just a woman who is blind and deaf.

She says I come from math.

She says I am married to Kierkegaard.

Or that I am like Kierkegaard in that I would never marry.

She says I should pay more attention to the girl.

She says I should ask about the Chaf Boy.

She says I have an important job.

She says I can see crossroads in time.

Once she said, “Hi, I am drunk in Turkey, I can’t explain it. Now’s not the time, we will talk later.”

John has come. He sits in a chair next to the bed and looks out with me at the dimly lit bookshelf. We don’t touch. None of this is like that. But it feels closer in any case, the intimacy of not talking, the intimacy of sharing our notes. “What’s a Pom?” John asks. “A British person, I think, or maybe an apple.” My notes are just about what I see, even in times like this, when I see almost nothing. John’s notes are always about time, even though he has so little of it. We all can only make the notes we make. That’s what we all have in common, a shame for our own limitations and an ability to see the beauty in the limitations of others.

But really, to spend so little time in wars, and so little time talking or eating or seeing? What is it we are doing?

When I open my eyes again, I am alone. The coming and going is easy. Even if I don’t hear from them for days or weeks or months, I never have the desire to hold on tightly. They are there, in a way, if I close my eyes. It’s the most real love I know, even if, I understand, as anyone could see, that I am truly alone.

••

I don’t ask the physicist what he is working on. I know he is working on a book about how time is real, and he has been working on it for years. If I ask him again, he would say again, “Ever since I was young, I have felt, in my heart, time isn’t real. But now, as I am getting older, I have started to change my mind.”

He has been getting older ever since we both started coming to this playground. We have a natural lack of enthusiasm for each other that makes it easy to stand together in a kind of quiet safety, especially with all the others minding children.

I know he would rather talk to me about painting, that he enjoys talking to me about physics as little as I enjoy talking to him about art. So I do not mention how it is only now that am I losing my good sense that time is real, that the good sense is just slipping right out of my heart. So I don’t say it is only now that time is completely slipping from me.

I watch my child on the spring horse, his back to me, looking off somewhere in the gray day, swaying only a little bit, the wind moving only a little bit around his hair, no birds around, everything feeling a little off. Like the part in Cocteau’s 1950 film when Orpheus is led out of hell by his chauffeur. We see just the back of the chauffeur’s head, his hair whipping around in the underworld wind, while Orpheus faces us, his pompadour unmoved, everything moving just a little bit wrong as Cocteau reversed the footage to let Orpheus walk out of hell, having fallen there from leaning over too far to hear the sweet words that come only from the underworld.

I think of the ugly word memories, the ugly word-cousin of the beautiful word time. Real movement in time is so much more elegant than muddied memories. But how can I really think time isn’t real—the invention of matches, the fires.

Some think it’s a terrible puzzle, the numbers that suggest time isn’t real. Some think the numbers are the problem. Some think it is better to not do the math at all. A few experts agree that numbers don’t seem to be real, as you can’t hide them inside a black hole. This is what makes something real, an infinite amount of information hidden inside a black hole.

Before he brings up painting and before I ask him about black holes, I ask if he has seen Cocteau’s Orpheus.

“Of course,” he says, relieved, a brief moment of eye contact. Orpheus is a story we’ve never gotten to the end of, as it’s never clear if someone who can slip into hell and slip out again, who can charm anything with their music, even the gods, even rocks, should be painted as a hero or a villain.

The physicist and I talk quietly in circles, time moving backward, Orpheus and the other poets getting into fistfights outside the cafes in Paris, the poets falling in love with death, who is just an ordinary princess dressed in black. We talk until it’s time to go home.

••

I pick up my kid. We walk back west, his head on my shoulder, the wind still gentle but colder. He whispers into my ear about the movie he will make when he is older, Trap Door of the Snakes, and all of the beautiful scary things that will happen.

“What do you want for your movie?” he asks.

“I don’t know.”

“You can pick from these: a princess, a bear, a cowboy, a doctor or a superhero.”

“No bad guys?” I ask.

“No, no, you mix them together and then they become a bad guy.”

“Oh, okay, I see, that sounds good.”

My movie will be about how I go back in time, to undo something that needs to be undone. But I know enough now to understand that I would just be able to go back to where I was before, back to my own body in time and place. I know my ideas couldn’t come with me. Just the body goes back. My ideas would turn back into thoughts, into sentences, then back into words or mush. And then you are just there like you are here. Useless.

I would open the door to the house, how I always open the door, and I wouldn’t remember why I had come, or come back, or that I was supposed to pay attention this time, or what I was to do. There are limits. The limits of acceleration. The speed of light isn’t the problem. The problem is acceleration, the terrible pressure of acceleration. How first the vision narrows and then goes dark, and then the body passes out, the pressure too challenging for our hearts to push the blood back up into our brains. The problem is about our hearts and the gravitational force.

Even astronauts have to lie down so the pressure goes across the body rather than from head to the toe. There are limits. With all the damage, we would not be thinking at all. Even if the acceleration was at a rate we could endure, it would take so long we would have forgotten why we were going. The only real way to go back would be through tunnels or tricks. I wrap my coat more tightly around us, thinking how at least sound travels faster when it is warm, though I don’t really know what that means, other than moving at the speed of sound also causes heart trouble and it’s against the law, because of all the noise.

–

Margaux Williamson is a painter from Toronto. Her most recent solo shows were at White Cube’s Hong Kong space and Bradley Ertaskiran in Montreal. Her newest paintings will be exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto Canada from April to August 2025.