Diary

Leonardo’s Masterpiece Revealed

A rare chance to see his restored mural in Milan

By Rachel Garrahan

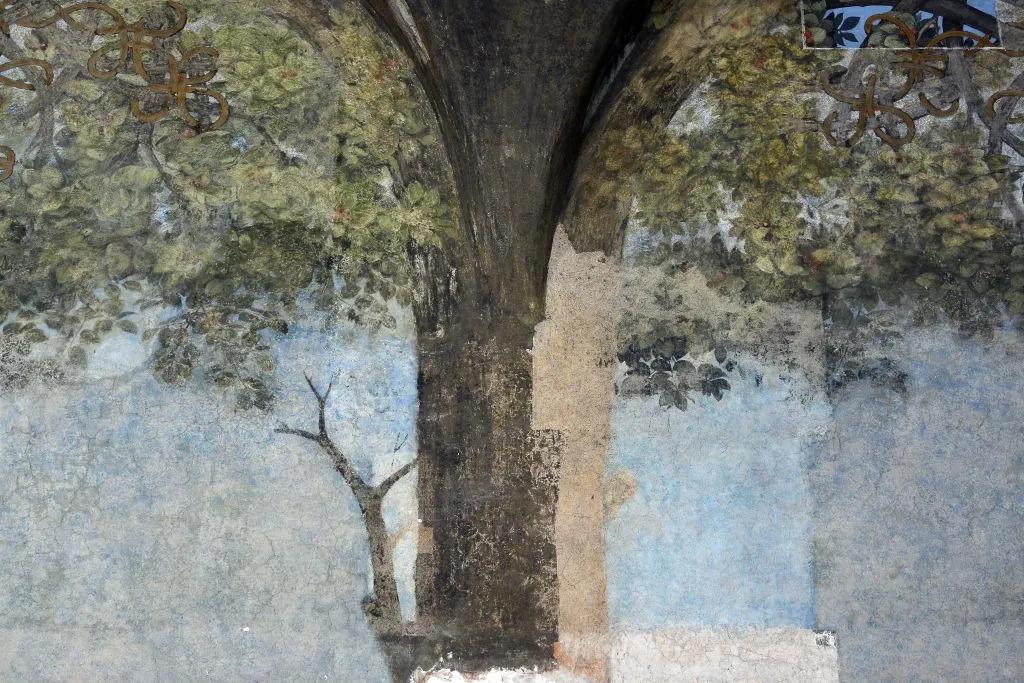

Detail of the Sala delle Asse mural by Leonardo da Vinci in Milan's Sforza Castle, which is currently open to the public during its restoration. Photo: Roberto Serra - Iguana Press / Getty Images

Sforza Castle’s squat towers and sprawling walls loom large over Milan. The city, which is currently buzzing with the Winter Olympics, its streets full of athletes in their countries’ brightly colored uniforms, offers an altogether different atmosphere inside the castle’s walls.

On the occasion of the winter games, art lovers have a rare opportunity to see a masterpiece mural by Leonardo da Vinci up close. A limited number of visitors (around 1,800 will be admitted over the course of five weeks) can don hard hats and climb scaffolding inside the Sala delle Asse to view restoration work to the thirty-six-foot-high ceiling which, together with the walls, is covered in Leonardo's vast unfinished artwork that depicts a giant arbor of mulberry trees.

Under cover of conservators’ scaffolding since 2011, the mural has been undergoing years of extensive restoration. Its temporary re-opening represents a unique moment, says Tommaso Sacchi, Milan’s deputy mayor for culture, to “get within millimeters of what Leonardo was doing with his brush.”

The Sala delle Asse was originally intended as a cavernous reception chamber for the castle’s owner, Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, who commissioned Leonardo to paint the mural in 1498, just a year before he was forced to flee ahead of the French invasion by Louis XII.

A ruthless political operator, Sforza was also a great patron of art and architecture, making his time in power the pinnacle of the Milanese Renaissance. Some believe his nickname of Il Moro (the Moor) was derived from the importance of the mulberry tree to the Lombardy region, where it was cultivated as a habitat for the silkworms that made it the European center of silk production. Another tradition believes the name derived from his dark hair and complexion.

Whatever the reason, Leonardo, who had been in Milan since around 1482, took the mulberry tree as his subject for the work. Using tempera paint, he and his studio depicted naturalistic fruit, leaves and branches that sprawl and intertwine across the upper part of the hall.

Restoration work reveals the fragility and endurance of Leonardo’s unfinished vision.

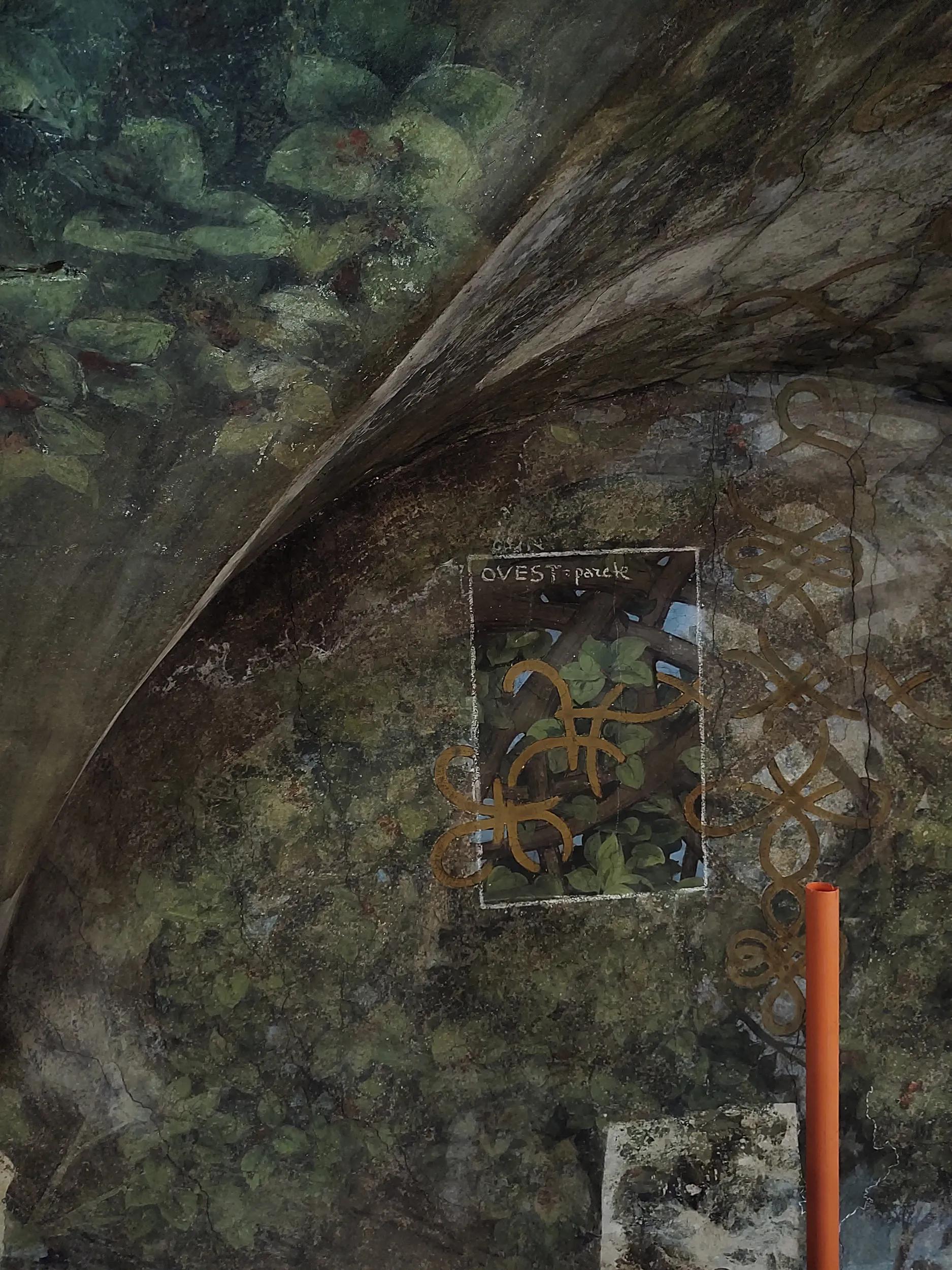

Recent conservation work reveals a detail from Ernesto Rusca’s 1901 restoration.

The mural was intended to intimidate the duke’s guests, says Luca Tosi, curator of paintings and sculptures at Sforza Castle Museums: “Imagine you are invited to this room and you are surrounded by these mulberry trees. It delivers the message that you are under the protection, but also the control, of the duke.”

The French invasion prevented Leonardo from finishing the mural, and for centuries it lay under layers of white plaster applied by subsequent rulers of Milan, who used the castle as a military complex.

It was finally rediscovered by architect Luca Beltrami following the return of the castle to the city’s ownership in 1893. He commissioned painter Ernesto Rusca to begin restoration. Based on visible fragments of Leonardo’s work, Rusca repainted the trees in a heavy, brightly saturated tempera that was quickly deemed to be excessive and incongruous with Leonardo’s naturalistic, soft sfumato style. Rusca's paintwork was almost completely removed in a subsequent restoration in 1954 by Ottemi Della Rotta, except for several small areas where it was retained as a record of the earlier restoration. “It’s not Leonardo-esque, it’s like a Liberty print,” says Tosi.

The latest round of conservation has utilized modern scientific research to uncover new elements of the painting, most notably in Leonardo’s impressive three-dimensional monochromes on the walls. Here, the force of nature is expressed in charcoal and ochre-based brushwork depicting tree roots that force their way through rock. Another section of monochrome showing the Milanese landscape stretching into the distance demonstrates Leonardo's skilled understanding of perspective.

The final stage of the restoration, before the room re-opens to the public next year, is the ceiling. Salt has been degrading the painting, pulling it away from the wall, and current visitors can see up close the conservators at work. They are treating the damage by painstakingly applying small sheets of Japanese rice paper soaked in demineralized water. The paper acts as a poultice that gently extracts the salt without removing Leonardo’s tempera paint. It is exactly the kind of natural technique that would have fascinated the Italian master himself.

–

Tickets for the temporary opening of the Sala delle Asse are sold out, but the Sforza Castle Museums remain open to visitors.

–

Rachel Garrahan is an award-winning editor, writer and curator. She co-curated the Victoria and Albert Museum’s major Cartier exhibition in 2025 and co-edited the accompanying publication. Previously at British Vogue, she is now the jewelry and watch director of the media platform EE72. She has contributed to publications including The New York Times and The Financial Times.