The Art That Made Me: Jeffrey Gibson

Ekow Eshun with the artist in his upstate New York studio

- 28 November 2025

- Issue 15

- This article is the first in a new editorial series created in partnership between Ursula magazine and Genesis.

- Related Artist

- Jeffrey Gibson

Jeffrey Gibson, the son of a civil engineer in the U.S. military, grew up in the United States, Germany and South Korea. A member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and of Cherokee descent, he was, as he recalls, “the kid who always drew,” encouraged to pursue art by his parents throughout his youth.

After studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Royal College of Art in London, Gibson built a career that bridges Indigenous traditions with modernist abstraction, queer identity and popular culture. His works bring together materials such as beadwork, fringe and rawhide with slogans, song lyrics and geometric pattern. He received a MacArthur Fellowship in 2019, was selected to represent the United States at the 60th Venice Biennale in 2024 and most recently unveiled The Animal That Therefore I Am, a suite of monumental sculptures for The Genesis Facade Commission at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

For The Art That Made Me, a new editorial series created in partnership between Ursula and Genesis, Jeffrey Gibson sat down with curator and writer Ekow Eshun to talk about the artists, artworks and cultural figures—from Madonna to Matisse to Leigh Bowery—that have shaped his work.

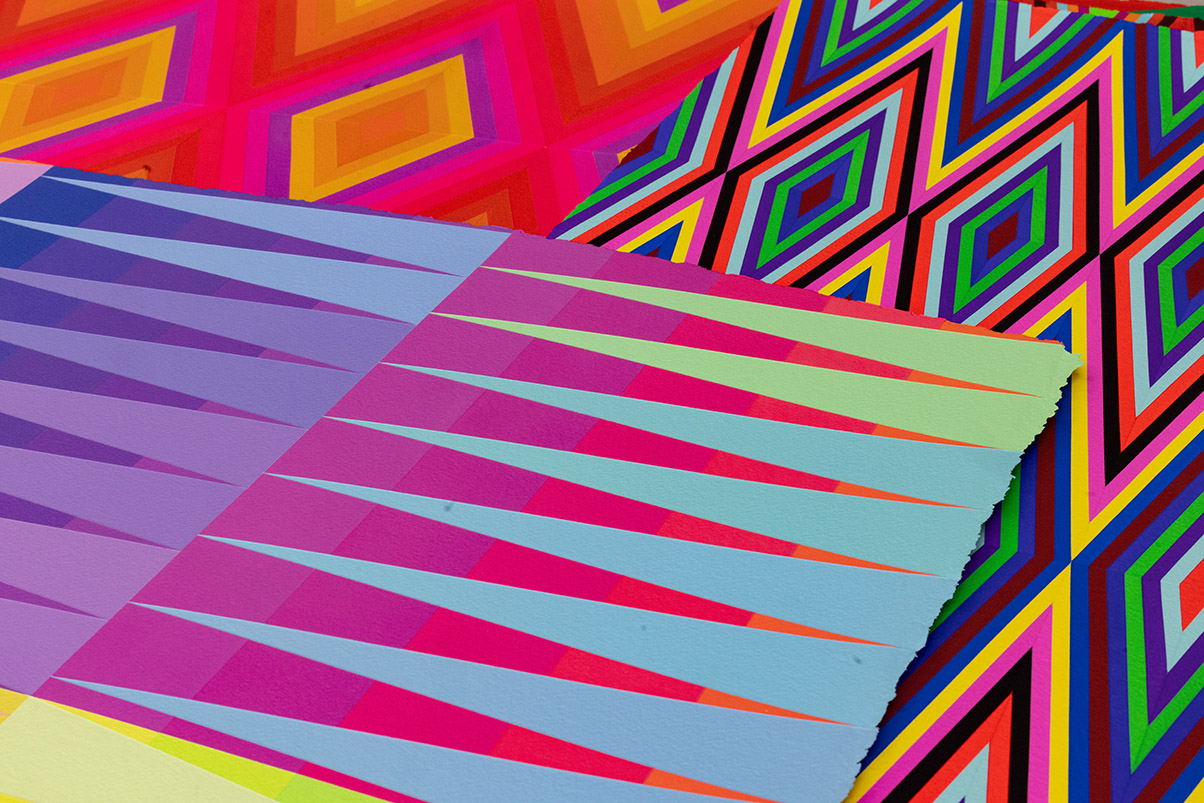

Jeffrey Gibson, Light Flares - The Sun is Calling, 2025 © Jeffrey Gibson Studio. Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein

Jeffrey Gibson, THIS IS DEDICATED TO THE ONE I LOVE, 2025 © Jeffrey Gibson Studio. Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein

Ekow Eshun: You were born in Colorado, but your upbringing and your work have taken you around the globe. How has that varied upbringing shaped who you are?

Jeffrey Gibson: We moved to North Carolina, then Germany, New Jersey, South Korea, Maryland. Then school in D.C., Chicago, grad school in London, and finally New York around 2000. Moving so much was not easy. I’ve never been placed neatly in terms of race, so abroad I was American, but in the U.S. I was immediately slotted into race and class structures, heritage and background. What I learned, sometimes to my benefit and sometimes to my detriment, was how to perform. And at the same time, I can be very forthcoming, sharing quickly so we can skip the surface and connect right away. Those two modes—detaching when I knew we’d soon move, or disarming openness to form quick bonds.

EE: Like a kind of a survival?

JG: Yeah, for sure. I think back to my parents, both born in the forties in Mississippi and Oklahoma. My dad served in Vietnam; the military was his way out of poverty. For me, after a lifetime of moving, comfort comes from motion itself. And initially there was discomfort in trying to settle down.

Photos: Beatriz Meseguer

EE: What values or traditions from your personal or cultural upbringing have you taken with you into the rest of your life?

JG: I think I have an incredible work ethic. Quite early on, my father told me: Life is not fair—you might have to work two or three times harder than the person next to you. If that’s what you want, then that’s what you’ll have to do. The unfairness was acknowledged, but never as a reason to stop. Both Choctaw and Cherokee people carry the lessons of survival, endurance and maintaining happiness and faith amidst life-altering challenges. Both my grandfathers were Southern Baptist ministers. They became ministers after struggling with alcoholism, and around that time they established churches where they preached and sang in Choctaw and Cherokee. As my father explained, those churches were as much about rebuilding communities that had been torn apart as they were about religion.

“I used to say that beauty—which was heavily criticized during my formative years—always carried a hidden agenda and there was a distrust of it. What I found is beauty is really this thing to draw someone in, to hold them just a little bit longer.”—Jeffrey Gibson

EE: Can you share a formative moment that shaped how you see the world or your place in it as an artist?

JG: I was born in 1972, so I became aware of the idea of being an artist in the mid-’80s. I was living in South Korea, and there was one hour of MTV from midnight to 1 a.m. They had Andy Warhol and Keith Haring create the commercials. That was my view of what was happening abroad. It took me a long time to say out loud, “I want to be an artist.” I got kicked out of my first year at university because I didn’t attend class. I went home and asked my father if I could enroll in a community college, and he said yes. So I went, and I was in the art department constantly.

There was a painting teacher who advised me on my portfolio, and another teacher who found me an internship with a sculptor in New Mexico. My painting teacher said, “You should go to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.” I trusted her so much that I didn’t question it. At the Art Institute, in retrospect, I didn’t realize how much freedom I had in Chicago at the time. Discovering house music in clubs was a whole education. Some clubs were very multicultural, mixed-race; others were predominantly Latino or Black. Because of how people perceived my heritage, I was welcome in all of those spaces. As much as I wanted to be in New York City, Chicago was absolutely the right place for me to be.

EE: Beyond visual art, can you select three artworks that have had a profound influence on you personally as well as creatively? These could be music, performance, anything at all.

JG: I’m almost a little bit embarrassed to say this, but I feel lucky that I was able to go to Madonna’s “Blond Ambition” tour in 1990. I remember begging my friends to go with me because people were like, “I don’t want to go to a Madonna concert.” But then we went, and it was just so fantastic. I’ve never seen anything like that again.

Fergus Greer, Leigh Bowery Session 1 / Look 2, 1988 © Fergus Greer (@fergusgreer._). Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery

Madonna, Blonde Ambition Tour, 1990. Photo: Gie Knaeps/Getty Images

EE: Tell me why that was important to you.

JG: At the time, she was provocative in terms of demanding acknowledgement of women, of gay people. She was forthrightly provocative about religion and morality and censorship. It was the AIDS crisis, and she acknowledged that. She was such a counter persona to what was happening in the world at that moment. And she did it so boldly. To see somebody so conscious of how they were operating—that was probably what the attraction was.

EE: It’s interesting, because much of what we’ve been talking about is access through heritage, through travel, to this range of influences. And what you’re describing with Madonna is someone who drew together religion, morality, sexuality, and turned them into performance, into a persona, a form of power.

JG: Yeah, absolutely. And I think when you grow up in that era, this era is a shock, because it felt so history-shifting. It laid the foundation for a future.

EE: What else?

JG: My father would always bring me back posters from his travels, and he brought me back a couple of Henri Matisse cut-out posters. When I was about seventeen, I saw the Matisse cut-outs at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. I remember being so excited to go and see them. I walked upstairs, turned the corner, and had no idea—they stretched across an entire wall. I had looked at this small poster the entire time, and each piece was huge. I remember feeling my blood pressure shoot up. I thought, “Oh my gosh, I can’t process this.” I had to leave the gallery, sit down, catch my breath and then make myself consciously walk back and forth in front of it and try to understand how you would make something like this. Seeing those photos of him in a wheelchair with a cane pushing the paper around—that was a real moment.

Henri Matisse, Large Decoration with Masks, 1953. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

EE: And what about something beyond visual art?

JG: Leigh Bowery. He passed two years before I came to London, in 1996. A roommate of mine said, “Have you ever heard about Leigh Bowery?” I said no. I lived in Herne Hill, just behind Brixton, and we talked about the Fridge [the renowned nightclub and music venue that opened in 1981]. When I learned about Leigh, I was blown away immediately. His body was similar to mine in terms of height and dimension. Seeing somebody so flamboyantly and unapologetically putting themselves on display—I always found his voice was one of real generosity. Then to see him go through performances like Minty or Useless Man, which is one of my favorite events—him hanging upside down and crashing through glass—and then of course his passing from AIDS. It’s all tied into that moment of individualism and strong characters.

“When you see individuals who, against many odds, not only cracked it open but tore the house down, you think, okay—it's possible. You just have to figure out your way in.”—Gibson

EE: Do you think seeing Madonna and Leigh Bowery helped you see yourself?

JG: Yeah. Seeing them really set up, for me at least, the question: Could you do that? It’s like someone throwing the gauntlet down: “Someone else did it. Can you?” As a young artist, you don’t know how far you’re going to have to go. And that loop of disappointment is really feeling like you’re never going to crack it open. So, when you see individuals who, against many odds, not only cracked it open but tore the house down, you think, okay—it’s possible. You just have to figure out your way in.

I think probably I experienced the loop of disappoint-ment that many artists do. But mine felt misunderstood—certainly culturally misunderstood. In the early 2000s, when I was painting, I was thinking about weaving, basketry, bullet holes in dresses taken off battlefields. When I drew a circle, or painted a dot, there was a spill-age coming out of it, which to me was visceral. To other people it was a formalist language of contrast, and I was like, “No, absolutely not.” So part of the disappointment was: Where’s my audience? When are they going to show up? Eventually I realized it wasn’t about quitting, but about saying: I’m not doing it this way anymore. This isn’t working. I’ll scrap it and figure out how to come back harder the next time.

EE: What did that rethinking involve, and how did you come back the next time?

JG: Literalness. I was resistant to wanting to do anything that felt too legibly Native American. One of the first things was to do small paintings on deer hide, and that was a wake-up moment. The literalism enabled me to talk about animals, about nature, about something so specific. I remember the show I did at the ICA in Boston in 2013. There were twenty panels. I said: You need to realize there are twenty animals in this room. Twenty unique animals who all lived different lives.

EE: The term visionary is often used to speak about artists whose work seems to reach beyond their own experience. Does that idea resonate with you, and are there fellow artists, present or past, whom you would consider visionaries?

JG: Oh yeah. I mean, Félix González-Torres was such a huge influence. I knew about his work through lectures and pictures and things like that, but the first time I really saw it was when they installed his retrospective for the Venice Biennale [in 2007.] That was significant to see. I would also say Magdalena Abakanowicz—those sculptural garments are such huge influences on the way I think about things. And Hélio Oiticica, the performance aspect of what he did, and the community aspect of those performances.

And then there are people like Sol LeWitt, Ellsworth Kelly, Bridget Riley, Agnes Martin. A very early influence is Matisse. But when I was in school—which would’ve been the early ’90s—Matisse wasn’t someone you were supposed to be looking at. Because it’s beautiful, it’s pretty, it’s about color, it’s pattern. At that time, we were being taught about new voices that were coming up, and about the political aspect of artworks, in that moment of real censorship.

EE: Your artworks are visually stunning and colorful and multilayered. But you’ve said the work is not “beautiful for beauty’s sake—the beauty is a strategy.” Can you talk about what that strategy is?

JG: Well, it’s wild because I used to say that beauty—which was heavily criticized during my formative years—always carried a hidden agenda, and there was a distrust of it. What I found is beauty is really this thing to draw someone in, to hold them just a little bit longer. But I don’t think about vapid beauty. I think about this intentional craft of something that is beautiful.

When I was working in Venice recently, I realized: We can look at objects made by Indigenous people over the past 200 years in times of trauma and duress. Why spend days, weeks, making gorgeous objects? I think it’s a manifestation of hope for a future. The focus required to make the object is remarkable. To me the beauty now is not just visual, it’s also the aura. Why did we ever want to get rid of the aura of an artwork?

“You don’t accidentally end up in a museum—it’s a destination. But the front of the building, someone riding their bike down Fifth Avenue or just hanging out, they’ll see it. I like the idea of an artwork landing for people in that way. I want viewers to be affected, intrigued to look longer.”—Gibson

Views of The Genesis Facade Commission: Jeffrey Gibson, The Animal That Therefore I Am, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2025–26 © Jeffrey Gibson Studio. Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, by Eugenia Burnett Tinsley

EE: As you worked recently on The Genesis Facade Commission at The Met, what did the opportunity mean to you? The Animal That Therefore I Am—that’s a great title from Jacques Derrida, who was writing about the relationships between point of inspiration?

JG: I read those lectures in the early 2000s, though they were given in 1997. By then, I had worked with Hélène Cixous and taught a class on Deleuze, so that kind of deconstructivist thinking was something I returned to. With The Met sculptures I wasn’t thinking about animals so much as animism—faith practices across global cultures, where people understood themselves in relation to the natural environment.

What I liked about Derrida’s lectures is that they’re really about the loss of empathy, the loss of seeing our-selves as part of the animal world. I’ve also used a deck of medicine cards with animal spirits, like a tarot deck, since my twenties. Returning to those while working on The Met felt like continuity, not something new—the Derrida lectures just brought it into sharper focus.

Courtesy Jeffrey Gibson Studio

EE: And the animals you chose—the deer, the coyote, the hawk, and the squirrel—why those in particular?

JG: Simply, they’re the animals I see. Hawks amazed me at first. Squirrels, ubiquitous New York animals, thriving because of our excess and waste. The deer was personal—when we first moved to the Hudson Valley, I saw a glowing white deer in the forest. It stood there, fifty feet away, and didn’t run. It came at a time of recommitment to art, the decision to have a family, to create a more sustainable life. It felt like a reset toward a calmer, more abundant future.

And the coyote connects most directly to being Native, through trickster stories I grew up hearing—some gruesome, others witty and humorous. Transformation has been on my mind for a long time. Even in my paintings, transparent colors transform one another in multiplicitous ways. Since making these sculptures, I’ve thought about other animals, but they’d still be ones I want in my immediate surroundings.

EE: Was there a moment in the process of making this work that surprised you—either creatively or emotionally?

JG: I work so much in the atmospheric things that surround us, so to choose an image and a form that is representational was probably the biggest surprise. I knew I wanted to do something that referred to cultural imagery about transformation.

When I landed on this sense of animism, I started thinking about times when I’ve seen humans wear garments to perform as animals, and about Indigenous dances based on animal movements. But it was important that the base of the sculptures is not the feet of the animals. They transform from the wood to the armature, to the base of hide wrapped around materials, to their adorned selves.

With The Met facade, it’s such a public space. You don’t accidentally end up in a museum—it’s a destination. But the front of the building, someone riding their bike down Fifth Avenue or just hanging out, they’ll see it. I like the idea of an artwork landing for people in that way. I want viewers to be affected, intrigued to look longer. That’s what completes the work for me. It’s an earnest attempt to create understanding. Not necessarily agreement—understanding.

And with these animals, I would say they’re ones we often overlook. Just as terms like “Indigenous” or “Native American” flatten the reality of hundreds of distinct tribal communities, so, too, does the word “animals” flatten the reality of thousands of species—including species we haven’t even discovered yet.

EE: What would you say to your younger self—the one just beginning to feel like an artist?

JG: A piece of advice that I was told, and that I continue to give other people, is: “Make your goal big enough for the sacrifices you’re going to have to make.” Because it’s easier to fight for something big than it is to be miserable over something small. And I think if someone can hear that, and really receive it, it’s very valuable.

–

The Genesis Facade Commission: Jeffrey Gibson, The Animal That Therefore I Am, remains on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, through June 9, 2026.

Reflecting a commitment to authenticity, Genesis seeks to foster dialogue on issues that transcend spatial and temporal boundaries, inspiring people to discover the profound through the arts. Genesis Art Initiatives supports institutions and visionaries with an understanding of contemporary challenges and timeless values. To learn more, follow #GenesisArtInitiatives.

–

“Jeffrey Gibson. This is dedicated to the one I love” is on view at Hauser & Wirth Paris through 20 December 2025.

–

Ekow Eshun is an author and curator. His book The Strangers: Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds That Made Them was published in 2025. For the Baltimore Museum of Art, he recently organized “Black Earth Rising,” an exhibition that explored the climate crisis through the eyes of contemporary artists.

Jeffrey Gibson is celebrated for his work in painting, installation, video and performance, which references global histories and interrogates the distinctions between craft and fine art. A member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and of Cherokee descent, he pursues a multidimensional practice that emphasizes collaboration and forges new platforms for Indigenous voices and makers.