Conversations

Bounded by Space

Alexander S. C. Rower, Jacques Herzog, Piet Oudolf and Juana Berrío on the creation of Calder Gardens in Philadelphia

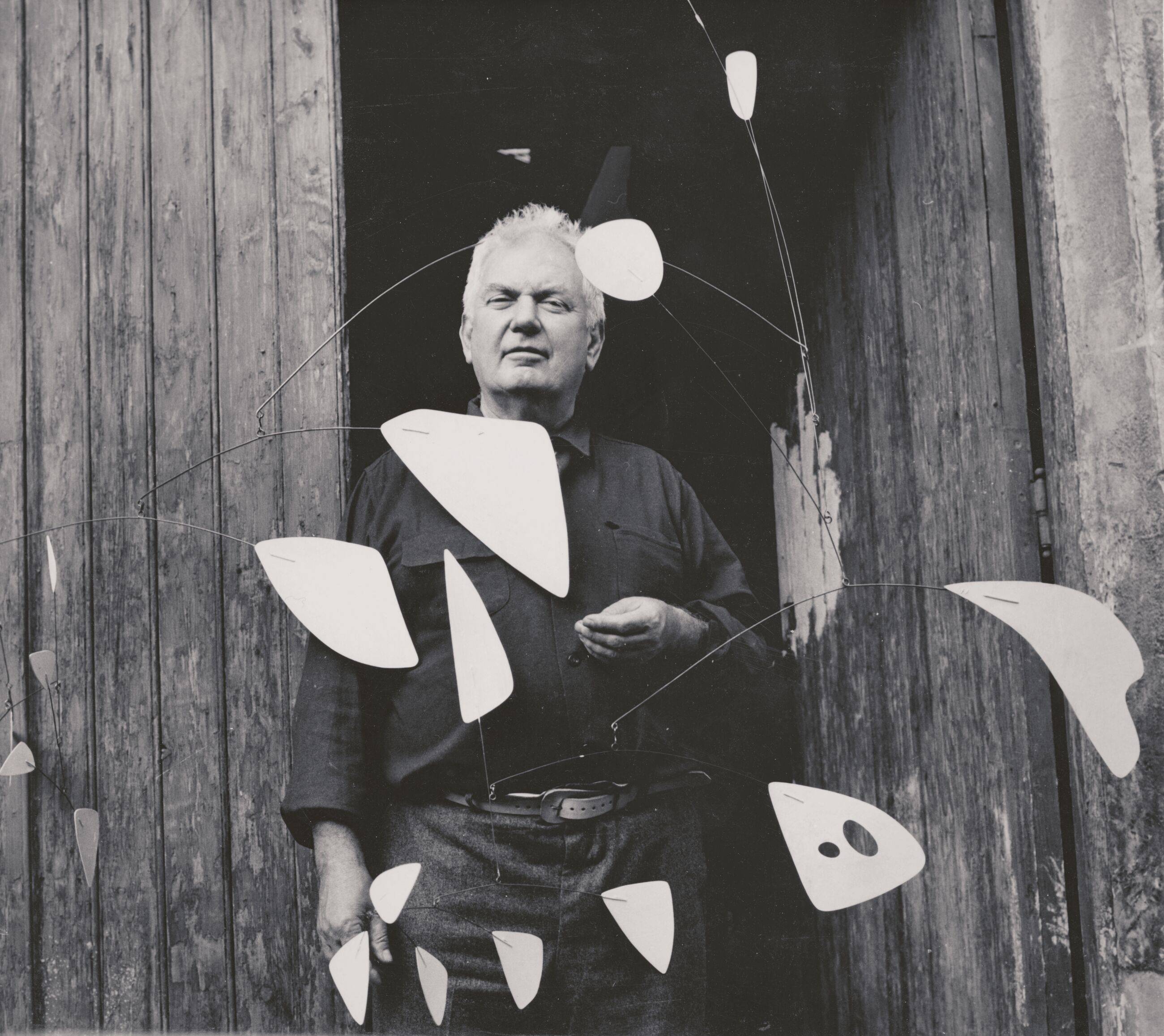

Alexander Calder, Jerusalem Stabile II (1976), photographed at Calder’s estate in Roxbury, Connecticut, in 2010. The work will be among the sculptures on view at Calder Gardens, Philadelphia © 2025 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York. Photo: Maria Robledo

Alexander S. C. Rower: A good place to start in talking about the idea of Calder Gardens is by going back to some things my grandfather said about his worldview and his views about art. In 1951, for a bulletin published by the Museum of Modern Art, he said: “That others grasp what I have in mind seems unessential, at least as long as they have something else in theirs.” That’s a critical sentiment to understand what was going on for him in that era. He was addressing the misunderstanding of his work, and in the 1950s and ‘60s, he essentially stops talking about it himself. He backs away from explaining, which means that the audience had to fill the void.

Even farther back, in 1931, he had said that his work had no meaning. But if an artist says, “My work has no meaning,” it doesn’t mean that it’s meaningless. It means that the artist is not predisposing you to an outcome. He’s saying: There’s no path you have to follow, which is exactly what Calder Gardens is. He was proposing that you keep not only an open mind but also, more importantly, an open heart as you approach his work. And as you approach life. Grandpa is saying, “Turn off all those outside influences and present yourself to my work.”

Calder with 21 feuilles blanches (1953), Paris, 1954 © 2025 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York. Photo © Agnès Varda Estate – Agnès Varda Photographic Archives on long-term loan to the Institut pour la photographie & Courtesy Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris-Bruxelles

The core of the idea for the project really began when my friend Isabela Mora got married at Ronchamp, in Le Corbusier’s Chapelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut. That was my first visit to Ronchamp. When you walk in and you turn left into the space and look up, there’s an incredible moment of darkness to light. It’s just mind-blowing. I wanted to hang a Calder there! [Laughs.] That experience led me to understand why I had always rejected the idea of a Calder museum—it was because I don’t like mausoleums, and the 19th-century model of a museum, which is still the predominant model, is not something that has ever resonated for me.

There have been so many proposals over the years to make a museum for Calder, and I was never interested in them. Then about eight years ago, I was called by a group of people in Philadelphia led by Joe Neubauer, who pitched me the idea of a hometown museum, in the city where my grandfather and his father and his grandfather had lived and worked. I told them I had no interest in a museum. And they were like, “Well, then what would you do?” I said, “Well, maybe I would make a chapel.”

And in a way, that’s what led to Jacques Herzog and Herzog & de Meuron. I had known Jacques for a while, socially, but we weren’t close friends. Some of our partners loved the firm and wanted to talk to them. So we had some meetings, and what I didn’t know is that . . . well, two things. One is that there was going to be a pandemic and it would give Jacques time to focus completely on this project, which was incredible. He made 600 drawings on paper. He hadn’t drawn like that for decades. And the other thing I didn’t know is that Jacques has been working on a chapel project in Switzerland, a kind of highway-side chapel. You pull over and go in and you have an experience of space and light and reflection and then you go on your way. This is an idea he has been developing for quite a few years and when we went to talk to him about making space for Calder that would not function as a museum but as kind of secular sacred space, he got so excited by it.

“[Calder] was proposing that you keep not only an open mind but also, more importantly, an open heart as you approach his work. And as you approach life. Grandpa is saying, ‘Turn off all those outside influences and present yourself to my work.’”—Alexander S. C. Rower

Jacques Herzog: The way Sandy [Alexander S. C. Rower] presented the project to us was wholly unlike a conventional architectural project. It was almost like a work of art. Not that I’m saying the structure is art, but, at the beginning, like an artist, I had no one telling me what to do or what the project should do and there was huge freedom. The only thing I knew was that it should be some kind of space for the work of Calder that was not a museum. There was no real brief or program, not even a precise site or zoning. So I was working very much based on trial and error. There was a kind of innocence to the whole thing.

AR: I kept telling our board chair, Marsha Perelman, and our partners, “I want to make it smaller. Let’s make it smaller. Let’s not have a restaurant. Let’s not try to be full-service. It needs to be human scale, not institutional scale. It needs to be about nature and people and have a feeling of intimacy.” I kept thinking about the environment that my grandfather grew up in. His parents’ artist friends were always all around. He grew up with the American Ashcan School, with John Sloan and so many other artists that were his father’s friends and teachers at the Art Students League. He also was deeply influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement, the anti-industrialization movement, by going back to the handmade. When Tiffany and Cartier proposed editioning his jewelry, for example, he told them no. He said: “If it wasn’t made by my hands, it won’t be imbued with my energy.”

JH: The first sketches that I made show some kind of a structure above ground, but that was a short moment in my thinking before I became aware that the work of Calder is so much about form and about color, which is also what architecture does. I realized it was exactly what I wanted to avoid. I didn’t want to do anything in architecture that evoked the work of Calder. I decided to focus more on space than on form.

That’s how I eventually oriented myself to the below-grade areas and digging and discovering, step by step, the spaces that make the structure. The more we worked on the idea of space rather than of volume and form, I became aware of the need for plants and nature. The idea of gardens, and of a sunken garden especially, suggested that the natural world should play a big role.

One thing I knew I wanted to avoid was any overtly religious elements or the pretentious ingredients that very often come alongside special rooms for art. The rooms should be unlikely and new and also natural. I wanted this ambiguity to be very present in the design.

I wanted the project to look like something that I hadn’t designed before. I wanted it to be, in a way, a no-design kind of architecture but purposively. I always admired, in the American landscape, the barn, a functional barn as part of a farm. Barns are iconic and invisible at the same time. The idea of the barn was also an unlikely structure in the context of these heroic museum buildings that are standing around Calder Gardens—the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Barnes Foundation and the Rodin Museum, which are all made to look like “real” art institutions.

Calder Gardens, 2025. Photo: Iwan Baan. Artwork Alexander Calder © 2025 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Piet Oudolf: I met Sandy at Hauser & Wirth in Somerset when was I finishing the garden for the gallery there. He said he liked my work, and then around 2020 he wrote me and said he was going to create a building for his grandfather and that he would love for me to consider making the gardens around it. I assumed it was going to be a museum for Calder. But then later in the ongoing conversation, when I met Sandy in Roxbury, Connecticut, with his family, he showed me around his grandfather’s studio and I saw the big Calder pieces in the field, and I had one of those moments when you think, “Oh, wait, this is something different. This could be great.”

Sometimes with jobs I get lucky. And I also really have no fear. I take on big jobs because I believe in what gardens can do for people. I’ve had so much experience by this point. And even though what Sandy wanted was unusual, unconventional, I thought: “If I can’t do it, who can?” That’s one of the reasons I’ve stepped into bigger projects than I probably otherwise would have over the years. With this one especially, I’ve always kept in mind that my work had to have respect for the art, that I should create something that didn’t fight the art but complemented it. I know that my work is dynamic. It is there. It’s very visible and grabs attention, but it should never overrule the art, if the art is good.

JH: At some point in the process I began experimenting with the idea of a wall. I didn’t want it to be just a garden wall. Ultimately, I thought about the wall being a reflective material, a metal surface, like a big mirror, so that the garden and works would be reflected in it. I thought: The wall should not really have a physical component, like a stone wall around a park but something more ephemeral, more fragile.

Calder Gardens, 2025. Photo: Iwan Baan. Artwork Alexander Calder © 2025 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“I see Calder like a score—a musical score, a choreographic score, a process with different rhythms, different tempos, different temperatures that accompany one another and create a composition that allows you to navigate spaces in different ways—physically, intellectually, emotionally, spiritually, too.”—Juana Berrío

AR: All along as we were working and planning, I kept the questions in my mind: How can you recreate that sense of awe that I had at Ronchamp? How can that be transposed into a place for art and humans and architecture and nature? How can all that be woven together to create an experiment that is a hopeful experiment, believing in the possibility of human evolution? How do we make those things coalesce so that people will, maybe without even knowing it, have their cells vibrate to a little bit more wakefulness as opposed to sleep-fulness?

JH: We’ve done quite a few museums during our career as a firm, and I increasingly think that the ways in which one experiences art need to be rethought and recreated for every generation. Institutions need to attract young people, even if some of the people are not really coming for culture in particular. Art places should be great places to be. I don’t mean like the Louvre, where there’s great art and architecture but where you have tens of thousands of people around you. That’s a different kind of mentality. Calder Gardens should feel more like a place where a school class is coming, where there are not too many people, where there are small places where one or two people can sit. It should be a place where you can just sit or wander and look, whether it’s at nature or art, with the kind of ease one has when one sits under a tree.

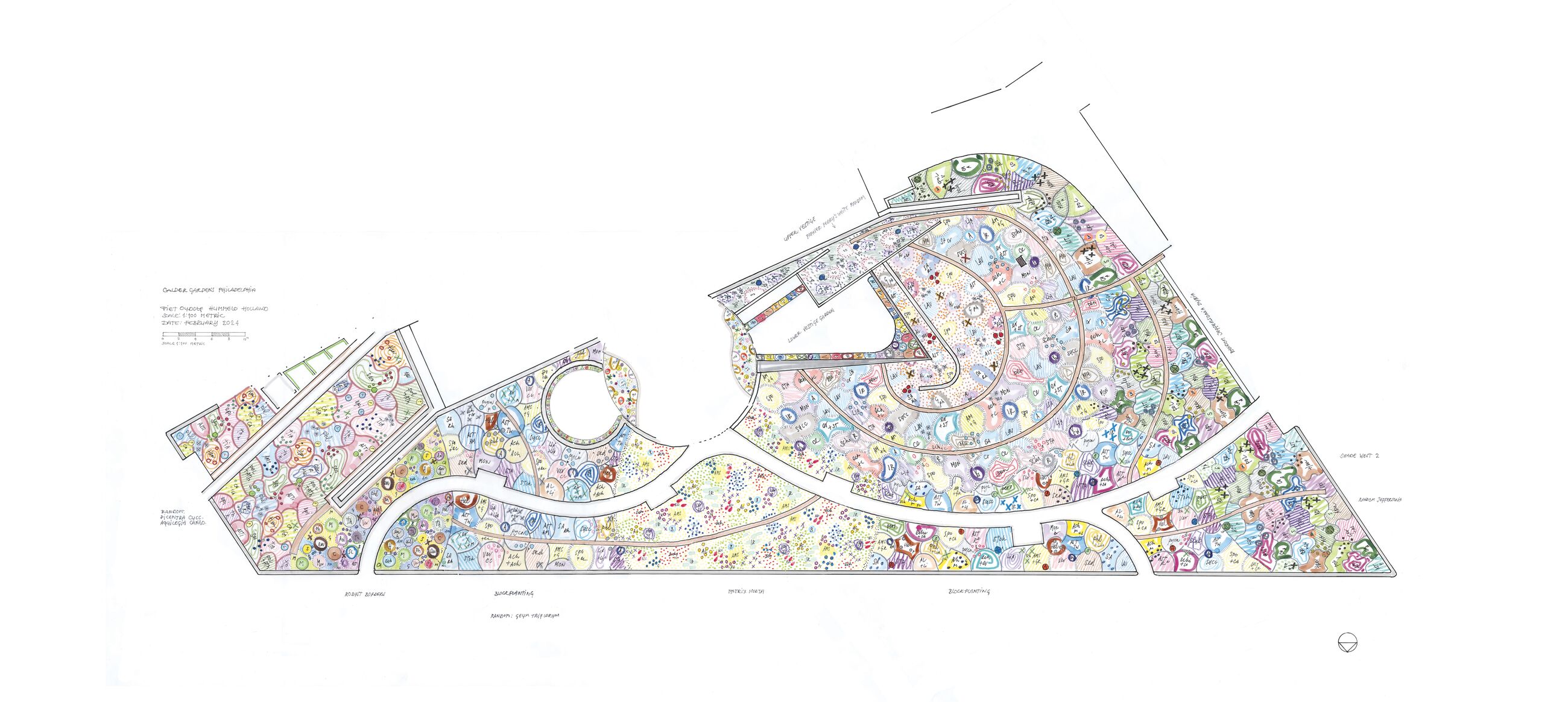

PO: I start by thinking about basic infrastructure. How will people walk or want to walk? You think about the pathways toward the entrance of the building. It’s very important how people will experience the gardens on their way to the pavilion. You decide about lines, how you want people to pass, go through the plantings. Once you’ve done that, then you start to think about trees and gardens to obscure the roads and the cars and take that out of the experience. So we want to enclose it on one end, but also open it on the other side. There will be an experience of walking into the site through trees and, suddenly, the garden opens up in front of you, and you look into an open garden that reveals the building as well. You move from woodland into more decorative, dynamic planting, and then into more a meadow planting. And then it changes again in a more robust planting, and then woodland again. You also have terraces that are planted with vines. You have to think of all these little things in parts. So woodland, block planting, meadow, robust planting, woodland. It’s difficult to explain how you make decisions for a garden. Every plant has its own character. If you see them as people, and you put them onstage together, they speak to each other and also to you. You try to get people to feel what you mean by putting them together.

Piet Oudolf, drawing of total planting plan for Calder Gardens, Philadelphia. Courtesy Piet Oudolf and Calder Gardens, Philadelphia

“It’s difficult to explain how you make decisions for a garden. Every plant has its own character. If you see them as people, and you put them onstage together, they speak to each other and also to you. You try to get people to feel what you mean by putting them together.”—Piet Oudolf

AR: Piet is such a veteran of work like this, dealing with art and architecture. What I didn’t realize is that there was going to be a whole process of value engineering, of things needing to shrink or change. Piet waited for all of these things to happen before he started working. He said, ”Why should I design a garden twice or three times?“ He wouldn’t start designing until all the concrete had been poured. He needed to think about the building being basically structurally finished. When he first came to Philadelphia and began siting the trees, I was with him. There was a place in the back of the plot with a cyclone fence, and on the other side of the fence was a little triangle of land. I said to Piet: “I really think you should consider that area outside the fence.” He was like, “Sandy, what are you talking about? It’s going to have this tree and this bush and these plants.” He’d already planned the whole thing. I thought he missed it because it was on the other side of the fence, but he had already taken everything into account, totally, completely, amazingly. He sites every tree, planned with elaborate drawings. His team follows those drawings, and then Piet comes and tunes everything. He’s meeting the trees for the first time, essentially. Eighty-year-old Piet is out there for the entire day, for the entire week, moving plant buckets a little bit closer or a little bit farther to create the naturalness he’s looking for. He’s literally sculpting nature in real time. He even specifies which part of the plants face which way.

JH: Calder’s work occupies a kind of unique space in modernism because it’s incredibly attractive for people who do not have an intellectual approach to art but also for those who do, who know the context in which he was working and his influences and his innovations. So one of the big goals for this project was not to interpret Calder but to offer as many different conditions as possible for the reception of the work. One of the spaces we created, which we call the apse space, is an egg-like shape, like the kind used by photographers for their studios, and walking in such a space gives you a sense of vertiginousness because you cannot orient yourself. I liked this very much in the context of Calder’s work because there’s the sense that it’s always moving, never stable.

AR: One of the big ideas that guided the creation of Calder Gardens was that there would be no exhibitions and no labels, didactics or guided tours. It’s just a sequence of gardens by Piet Oudolf and a sequence of rooms by Jacques Herzog—and of spaces in light, some of which are outdoors—where you can experience Calder’s work. Things will change and things will happen. We might take a piece out and put a different piece in. We might take three pieces from here and put them over there, moving things, reorganizing, trusting that the audience can have experiences without being told how to have them. So one of the guiding principles was about activating space. You’ve got to create a space and activate it in a way in which something mysterious can happen.

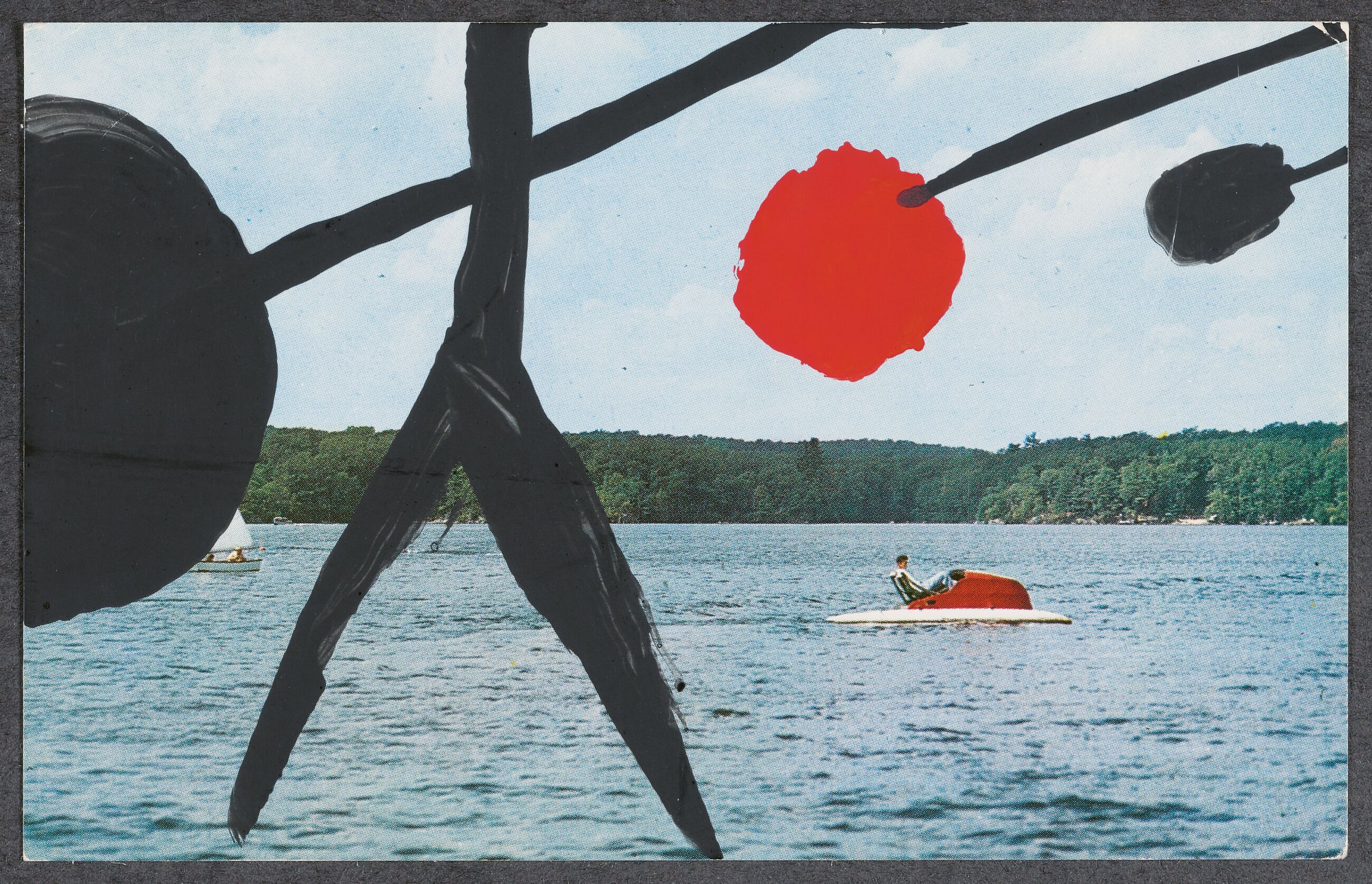

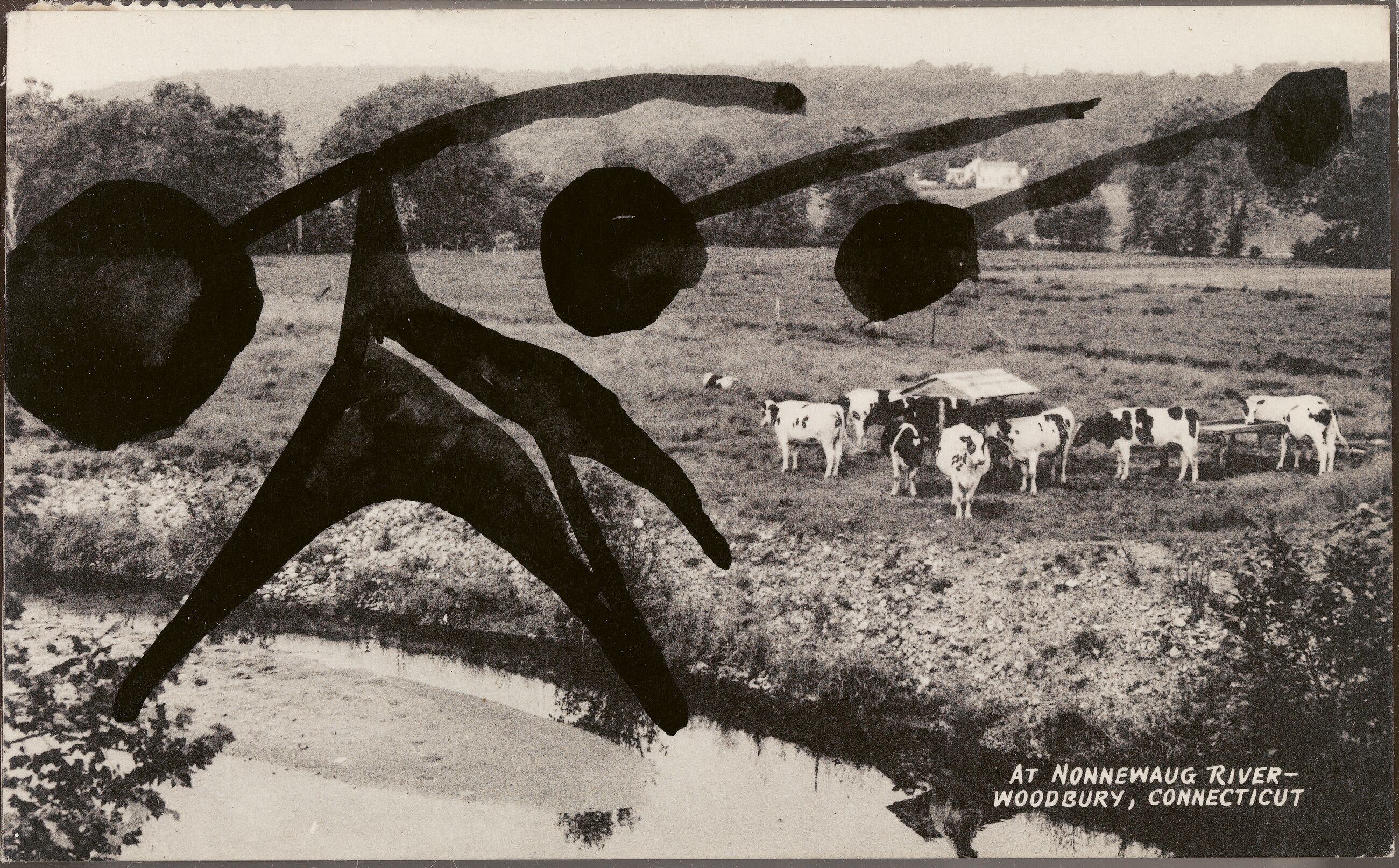

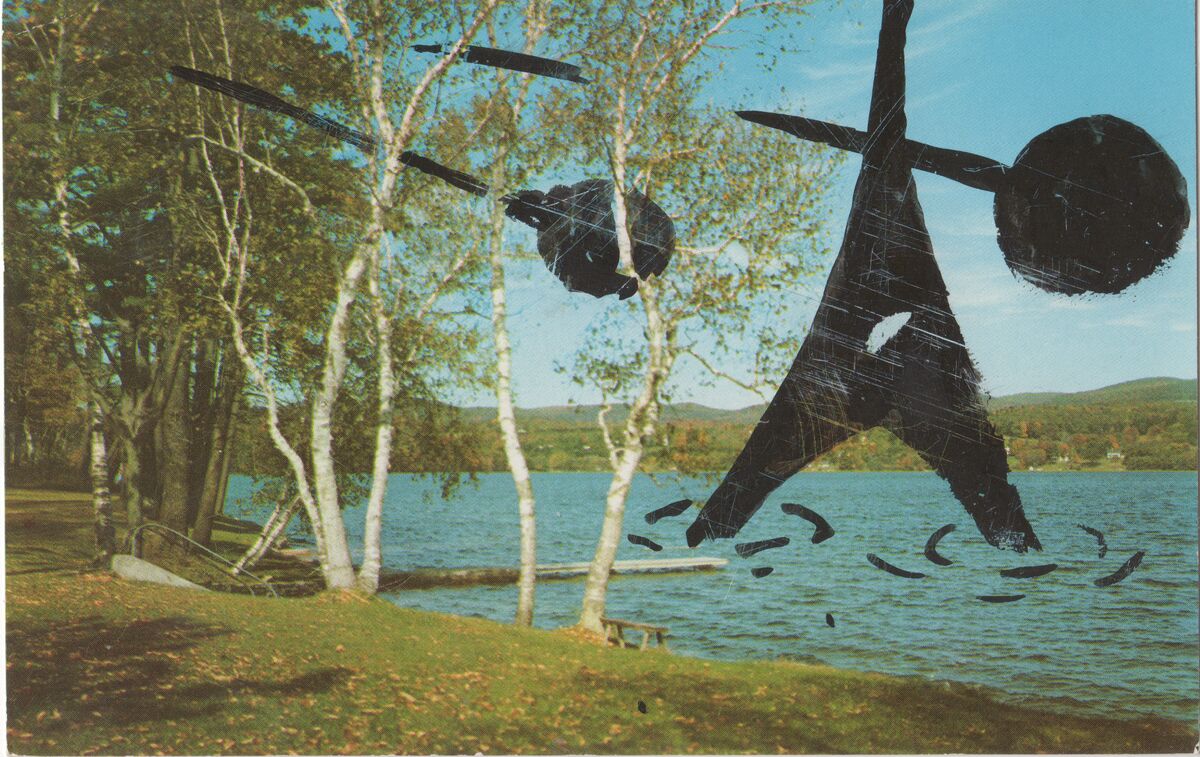

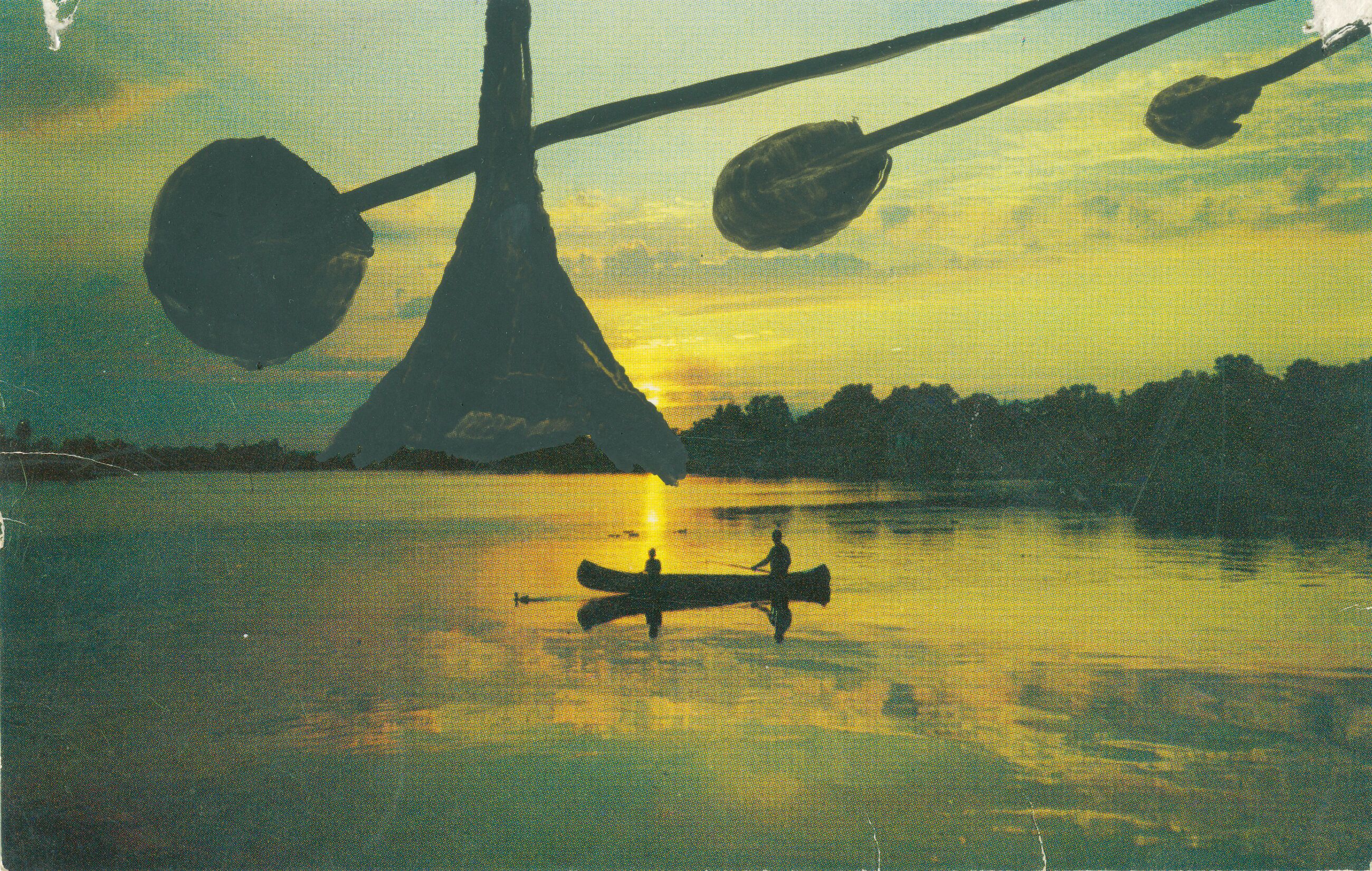

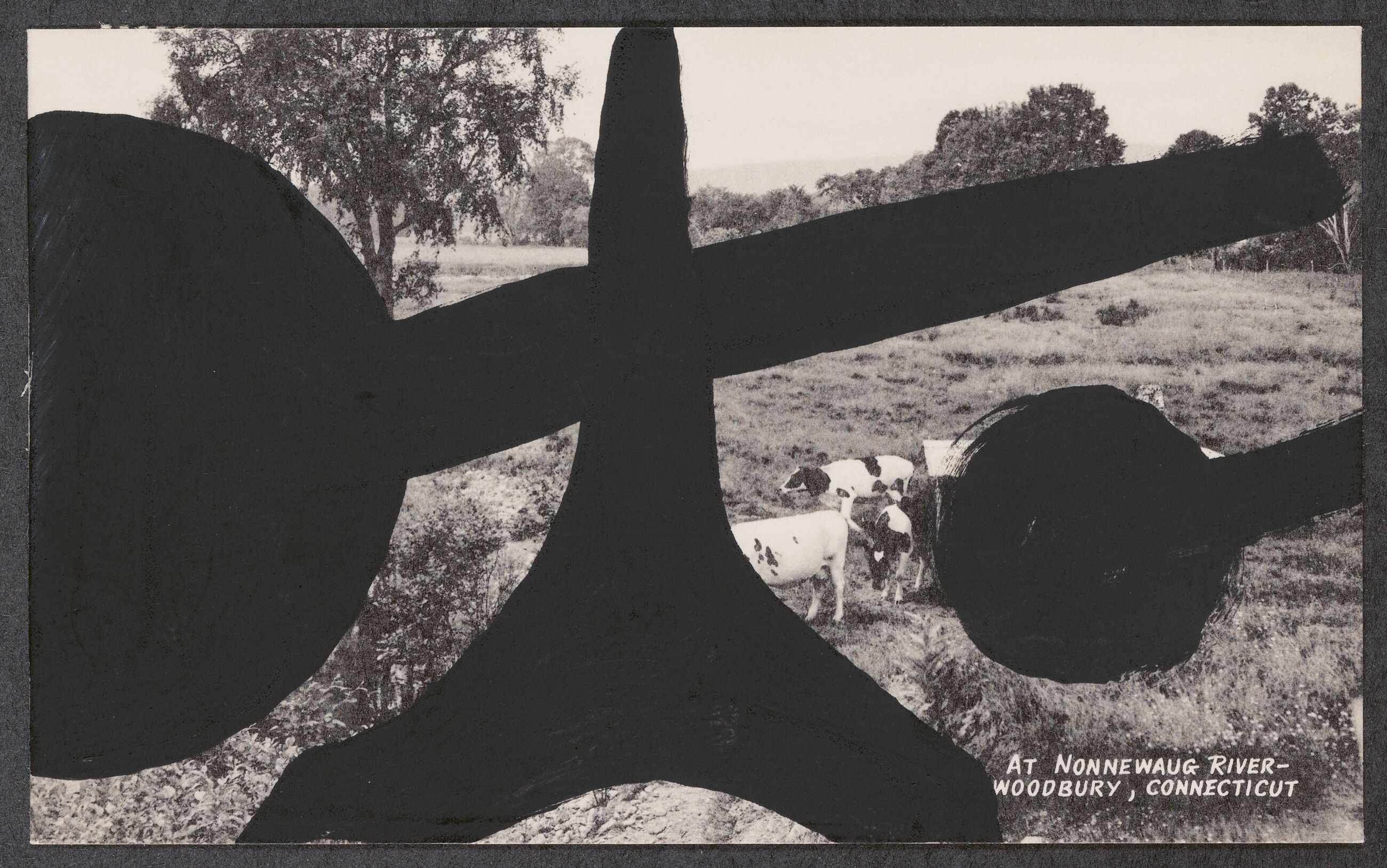

Alexander Calder, hand-drawn interventions on postcards, 1958–59 © 2025 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Juana Berrío: When they approached me for the job of program director, it was really interesting to see how the whole project was presented as a holistic ecosystem of the work of Calder and all the elements that come along with it. It’s not just the sculptures or the artworks. His legacy goes beyond the objects. He was an artist who really experimented with different mediums, collaborated with different disciplines. He pushed boundaries. He was a pioneer of performance art with his Cirque Calder (1926–31). Movement is really important to the sculpture, and also to what happens within you while experiencing it.

That’s why one of the elements we’re embracing is the notion of real-time experience. It’s not just the finished product of the artwork that’s there to admire. It’s our relationship with Calder’s gestures, with his process, that was constantly changing. We would like people to leave the gardens thinking about what they learned about themselves as opposed to, “What did I learn about Calder?” We don’t have to do more of that. There’s already so much information out there that is easily accessible about Calder.

AR: We hired Juana because we knew she would be able to bring in a kind of dynamic that went way beyond institutional programming, things that could tell us about our connection with nature and ourselves and art, things that would bring in incredibly diverse groups of creative people to help us do that. Already, for example, we’ve been engaging with the Lenape, who inhabited the land that became Philadelphia, to come in and conduct ceremonies. We’ve done two now; one was at the groundbreaking. The tribe asked for a red cedar and Piet got a magnificent example. They wanted a red cedar because it’s where their origin story begins; all humanity comes from the red cedar. For the ceremony, they brought fifty elders and had a fresh shad fish, which they buried under the red cedar tree. They all participated in the ceremony. It was an incredible moment.

JB: I see Calder like a score—a musical score, a choreographic score, a process with different rhythms, different tempos, different temperatures that accompany one another and create a composition that allows you to navigate spaces in different ways—physically, intellectually, emotionally, spiritually, too. We’re going to be focusing a lot on the seasons. I discussed with Piet a concept that we’re both really passionate about, which is connected to impermanence: the notion of decay and how beautiful and important it is to embrace decay instead of hiding it or removing it. In the garden, the decay will be on display in the fall and winter, when the flowers disappear and you have still the dead heads of the flowers and how beautiful it is to see that and how it leads to regeneration in the spring.

With the ephemeral commissions that we will begin to do with performers and musicians throughout the garden, the guiding thought is that every time we should be listening to different voices of artists being channeled through Calder Gardens. It should sound like an artist or a constant series of changing artists as opposed to an institution that has a permanent voice that is telling you exactly what you’re supposed to learn or how you should think about certain elements there.

Alexander Calder, hand-drawn interventions on postcards, 1958 © 2025 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“I wanted the project to look like something that I hadn’t designed before. I wanted it to be, in a way, a no-design kind of architecture but purposively. I always admired, in the American landscape, the barn, a functional barn as part of a farm. Barns are iconic and invisible at the same time.”—Jacques Herzog

JH: One of the reasons Calder Gardens includes these very different and somehow almost unlikely spaces is that Calder’s work can look great in diverse situations. It looks great in a concrete, defined space, like a white cube gallery. But it also looks great in a space with no clear dramatic definition, like the apse gallery, or in garden or meadow spaces. And the feeling of these unlikely spaces will, I think, echo and mirror what Juana will be doing with the day-to-day life and the gardens and the people she will bring in.

I have to say that the whole process of making most of the decisions for this project was very honest. Sandy likes intuition-based work, and the decisions and questions that I raised in my calls and emails and in my drawings were very exploratory. I would tell him, “Sometimes you have to drop something that looks so good at first sight but then somehow becomes disturbing or worrying.” You have to give it up and make very tough decisions, and I was speaking to the Calder Foundation about all of these things. I love that kind of honesty and directness in my communication with our best clients. It’s really cool. If you have a client in front of whom you can lay out the whole process of your thinking, it’s so much more interesting for the client because, in a sense, they become a part of the design team.

AR: I think that kind of mindset comes in large part from my grandfather. As a boy, I used to watch him work, and he was not consciously working when he was working. I would call it channeling, literally. If you go back to the beginning of the century, the people that were spiritualists were pulling things from other places, other sources, other dimensions. They were tapping into harmonies at a higher frequency than our three-dimensional world. That’s what he was doing, too. But he never spoke about that in overtly spiritual or even mystical ways. He felt the energy. A lot of people don’t. It’s important to remember, also, that he always thought about the wider world around his work, in the largest possible sense. In 1932 he wrote: “How can art be realized? Out of volumes, motion, spaces bounded by the great space, the universe.”

Alexander Calder, hand-drawn interventions on postcards, 1958 © 2025 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“Even though [Calder’s] work is not straightforwardly political, his goal was to get humans to be a little bit more aware . . . If we could all be a little bit more aware, maybe there wouldn’t be so much misunderstanding or violence or suffering.”—Rower

JB: For the grand opening, as a way to set the stage for the kinds of things we want Calder Gardens to represent and people to expect, we’re proposing a parade. The genesis of the project is, of course, that Calder’s father and grandfather lived and worked in Philadelphia. In Logan Circle, the Swann Memorial Fountain is by his father, Alexander Stirling Calder. The William Penn sculpture on top of city hall is by Calder’s grandfather, Alexander Milne Calder. And now Calder is coming to the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. It’s a beautiful lineage. We want to celebrate that with a very local focus and we also want to celebrate the fact that Calder was completely passionate about the circus. It was not just entertainment for him. It was a higher art form that presented so many options for movement and interactions and frictions and unexpected things to happen.

We’ll start at John F. Kennedy Plaza, known as Love Park, right behind city hall. You can see the William Penn sculpture from there. Then we’ll walk onto Logan Circle, where the fountain is, and from there to Calder Gardens and a little bit beyond on the parkway. We’re planning to have Sun Ra Arkestra, Pig Iron Theatre Company, the Bearded Ladies Cabaret, many different groups that function as collectives and that will bring different energies. There will be drum lines, really amazing, talented people from different generations playing drums; samba drummers; emcees who are also drag queens. It’s going to be a multiplicity of voices, like what you would experience in a circus. This is all about creating a willingness to make space for others, about being grateful for their traditions—that those traditions haven’t been crushed completely, that people are reviving their traditions and we are all assisting them.

AR: It’s all going to evolve, in ways that we don’t yet know and that we can’t predict. The strategy is to allow the place to tell us when it needs something else. If we take out a big sculpture, it’s not just because it’s needed somewhere else. It’s because it’s ready to move, and Calder Gardens is ready for change. The place needs to breathe a new breath, and we need to bring in a new sculpture, to exchange and move things, to make a new way to activate the place, a new way to be present with the work. My grandfather was vehemently against the Vietnam War, vehemently against all war. Nuclear proliferation was something that was completely insane to him. He took out a full-page ad in The New York Times on January 2, 1966, with my grand-mother, making this political statement: “Reason is not treason.” This is directly relevant to his work. Even though his work is not straightforwardly political, his goal was to get humans to be a little bit more aware, more self-aware. If we could all be a little bit more aware, maybe there wouldn’t be so much misunderstanding or violence or suffering. He was hoping that without him telling you how to feel, and how to react, and what to think in front of his work, something could naturally evolve and erupt in you. Maybe your life would be improved ever so slightly, in a way you might not be able to explain or even be conscious of. He hoped such experiences could be the fulcrum that tilted you toward greater awareness, greater enlightenment.

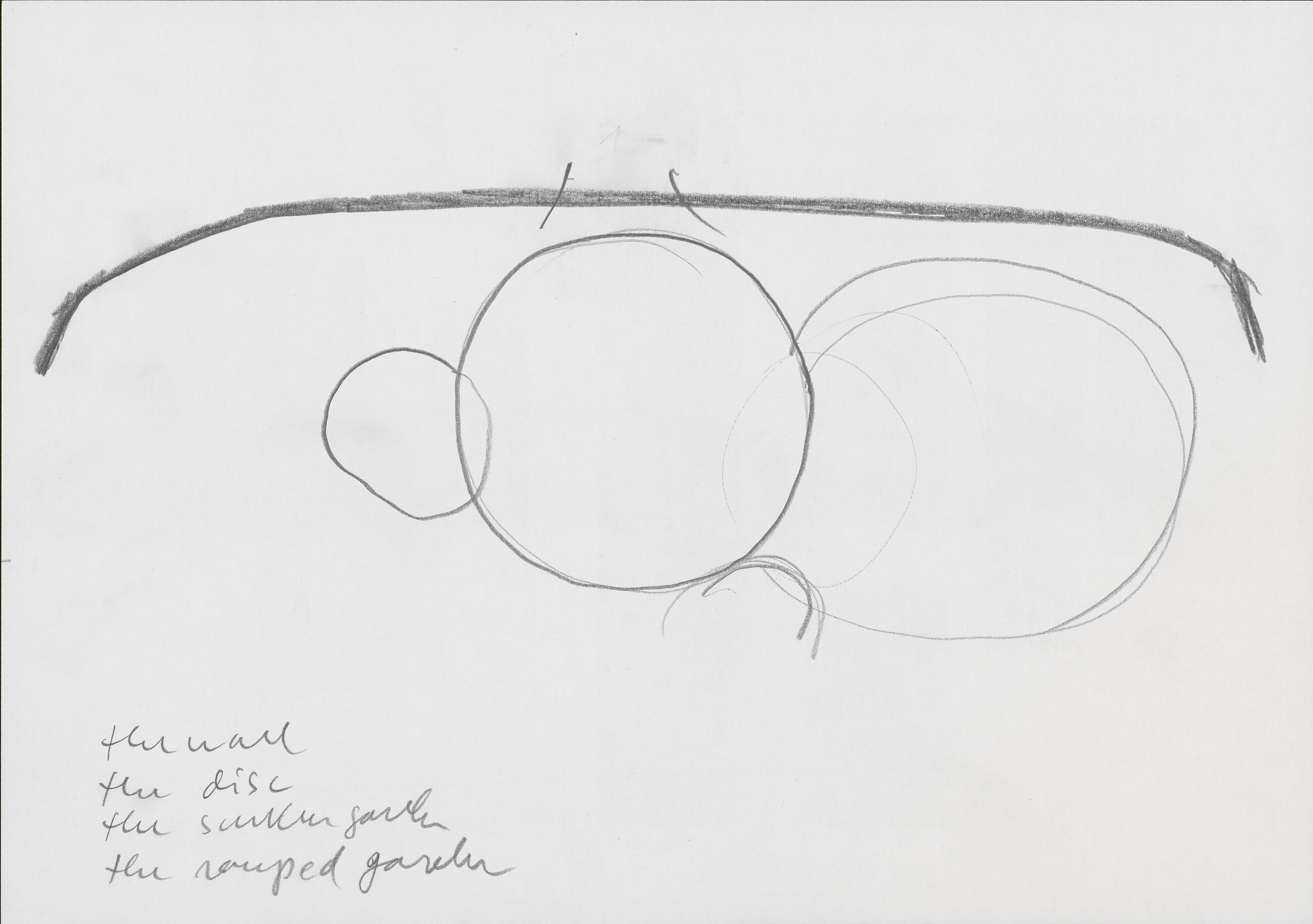

Jacques Herzog, drawing for Calder Gardens, Philadelphia, May 2020 © 2025, Jacques Herzog und Pierre de Meuron Kabinett, Basel. All rights reserved

Herzog & de Meuron, model of Calder Gardens, Philadelphia. Courtesy Herzog & de Meuron and Hauser & Wirth Publishers

–

Calder Gardens: Drawings and Texts by Jacques Herzog is available from Hauser & Wirth Publishers in October 2025.

Calder Gardens opens 21 September 2025 in Philadelphia.

–

Juana Berrío is a New York-based curator, educator, arts programmer and writer from Colombia. She is the Marsha Perelman Senior Director of Programs at Calder Gardens in Philadelphia and also serves as the curatorial and sustainability advisor at the Whitney’s Independent Study Program.

Jacques Herzog founded Herzog & de Meuron in 1978 with Pierre de Meuron. Herzog was a visiting professor at Harvard GSD, Cornell AAP and the ETH, where he and de Meuron co-founded the ETH Studio Basel, Contemporary City Institute. Their honors include the Pritzker Architecture Prize, RIBA Royal Gold Medal and Praemium Imperiale.

Piet Oudolf is an internationally-renowned landscape designer and leading figure of the New Perennials movement, which focuses on creating dynamic, naturalistic gardens that evolve with the seasons. His projects include plant design for the Lurie Garden, Chicago (2001); the High Line, New York (2009); Serpentine Pavilion, London (2011); and the Venice Biennale (2010).

Alexander S. C. Rower is the grandson of Alexander Calder and president of the Calder Foundation. Since founding the nonprofit in 1987, Rower has documented more than 22,000 Calder works, established an extensive archive and collaborated on more than 100 exhibitions worldwide.