Books

Book Stack

Some new and forthcoming titles we love

Otherhow: Essays and Documents on Art and Disability 1985–2024 by Joseph Grigely (Primary Information)

Joseph Grigely has long been one of my favorite artists-as-writers. Maybe it’s his love of fly-fishing or the fact that he lives and works in Chicago that brings Hemingway to mind when I read him. But the connection is really more about an essential clarity of thought. Grigely wrote for this magazine in 2019, a wonderful piece about making art only for oneself, in his case piling stones in remote quarries. “If things had gone a bit differently,” he began, “I might have become a bricklayer instead of an artist.” His writing possesses that kind of solidity. And because his subject is often communication itself (Grigely has been deaf since the age of ten), his sentences seem to perform double duty. This superb collection is the first to gather all of his writing, much of it about the complex cultural mechanics of disability. “Disability is always latent,” he once observed, “always potential, and trying to get people to embrace disability means trying to get them to embrace what they fear.”

—Randy Kennedy

Things That Disappear by Jenny Erpenbeck, translated by Kurt Beals (New Directions)

What remains when the fabric of daily life—its objects, habits, rituals—falls away? Jenny Erpenbeck’s Things That Disappear catalogues thirty-one such vanishings, from the trivial and amusing (a missing sock, an impulsive cheese purchase) to the devastating: her son’s preschool, a parliament building, a country. First published as a series of feuilletons—short columns for the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung—this book of essays hovers between memoir and philosophical inquiry, each piece animated by the author’s clear-eyed wit.

Born in East Berlin in 1967, Erpenbeck came of age in a country that dissolved before she turned thirty. “Things disappear when they are deprived of their means for existence,” she observes, her tone not nostalgic but searching. In her hands, East Germany’s disappearance becomes a refusal of forgetting—a way of keeping faith with what history would prefer to discard.

Compact enough to slip into a coat pocket, this slender book invites rereading anytime. To name what’s gone is to keep it alive, as long as we can.

—Alexandra Vargo

Stay away from nothing by Paul Thek and Peter Hujar, edited by Francis Schichtel (Primary Information)

It is believed that Paul Thek and Peter Hujar first met in the winter of 1956 when Hujar, on a road trip with a classmate of Thek’s from Cooper Union, visited the artist and his then-partner, the set designer Peter Harvey. By the spring of 1960, Thek and Hujar were both living in New York and had become lovers. Over the following decades, their intimate friendship would anchor both men. Stay away from nothing presents a portrait of their relationship as constructed through photographs and letters. Thek’s voice emerges as the dominant one (no letters from Hujar to Thek survive; as Andrew Durbin explains in the book’s afterword, Thek was hardly a diligent record keeper). Hujar instead appears in fragments: “Your depression letter just arrived,” Thek writes him in early October 1962. Their correspondence follows their travels, both alone and together, though Thek is the itinerant one—his letters chart a winding trail through Rome, Palermo, Amsterdam, Germany and Norway. Hujar’s photographs of their time together are interspersed with Thek’s words, rupturing their long periods of separation.

—Susannah Faber

Susan Rothenberg: The Weather, edited and introduced by Alexis Lowry (Hauser & Wirth Publishers)

“What is not weather?” ask Alice Oswald and Paul Keegan in the foreword to their anthology Gigantic Cinema. To concentrate on the weather, they observe, is to attend to “things that are invisible, ephemeral, sudden, catastrophic: air’s manifold appearances.” Susan Rothenberg: The Weather is a monument to the prodigious painter’s attunement to such mysterious forces. “The weather” is what Rothenberg called the dense textures that formed the backgrounds of her paintings; it could also allude to the oneiric mood her paintings produce, at once “abstract and visceral,” as Joan Jonas writes in her essay for this catalogue. Published for her 2025 exhibition of the same name, The Weather focuses on little seen and never previously exhibited works. Informative, poetic and carefully compiled, the book brings together six writers who reflect on specific paintings. Together, they provide a thoroughgoing tour of Rothenberg’s sensibility and the principles that guided her singular oeuvre. “I’ve always been circling the same few things,” Rothenberg said in 1987. “Time, space, composition, smoke, air, light, shadows.”

—Janique Vigier

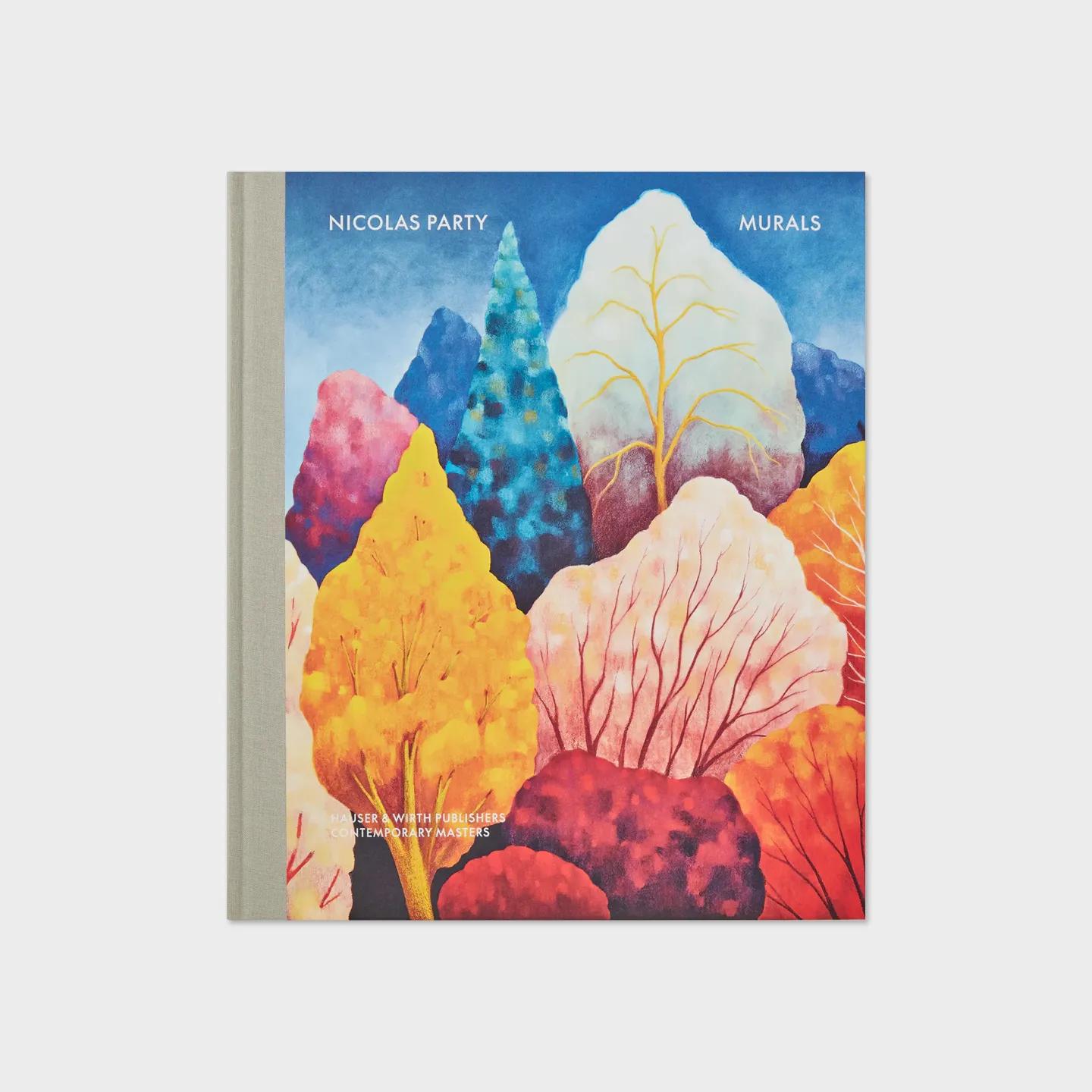

Nicolas Party: Murals, text by Jamilee Lacy and Nicolas Party (Hauser & Wirth Publishers)

When it comes to the work of Nicolas Party, mural is a capacious term. This point is illustrated vividly in Nicolas Party: Murals, a visual chronicle of Party’s most ambitious works of the past fifteen years. The works featured in it are “wall-based,” but, as noted in the engaging introductory essay by Jamilee Lacy, Party’s practice combines painted objects, walls and surfaces in ways that complicate the categories of artwork and environment, figure and ground, subject and support.

Murals traces Party’s development of a distinctive visual language that revels in the uncanny, the illogical and the absurd, alongside a characteristic whimsy and humor. Readers come away with an appreciation of his deep dialogue with art history, especially with Surrealism, and of his experimentation with the genres of landscape, portraiture and still life. They also understand the centrality in his work of pastel, a delicate and ephemeral medium that he wields in ways decidedly at odds with the techniques of traditional mural painting.

Accompanied by illuminating commentaries by Party himself, Murals captures the range and variety of an artist who is as ferociously committed to his craft as he is inspired by art history.

—Melissa Hyde

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: la règle des courbes / The Rule of Curves, text by Briony Fer and Jenny Nachtigall (Hauser & Wirth Publishers)

In recent years, Sophie Taeuber-Arp has started to receive the serious attention she deserves as a key figure in the European avant-garde of the early twentieth century. A new study explores her practice of setting circles and curves against the rectilinear structure of the modernist grid. The publication of this handsome clothbound volume, with essays in French and English by Briony Fer and Jenny Nachtigall, coincides with an exhibition of Taeuber-Arp’s work at Hauser & Wirth Paris in early 2026. Fer, the curator, suggests that Taeuber-Arp’s background in the applied arts, with an emphasis on textiles rather than on painting and sculpture, led to her distinctive style. Nachtigall’s essay examines Taeuber-Arp’s training in dance, noting that she first learned how to draw lines with her body, then translated that movement into materials, including textiles and paper. Marcel Duchamp once wrote that Taeuber-Arp introduced the “geometric arabesque” into modern art. That’s a good description of the stunning reproductions in the book. Whether in black-and-white or color, they are bold, playful, endlessly inventive—and a pleasure to look at.

—Ann Levin

What I’m Reading—Christina Quarles

Christina Quarles in her Los Angeles studio, 2025. Photo: Joyce Kim

Earlier this summer I read Miranda July’s All Fours. I loved it but regretted not listening to the audiobook. Since then, I’ve been on an audiobook kick. Recent favorites have been Donna Tartt’s The Secret History and Bret Easton Ellis’s The Shards, each read by the author and a great back-to-back experience. I just finished listening to Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer, a sci-fi-horror novel that follows a team of four women on an expedition to a black site called Area X. It was a short listen, but I think it influenced a particularly swampy section of a painting I’m working on right now.

—Christina Quarles