Books

Book Stack

Some new and forthcoming titles we love

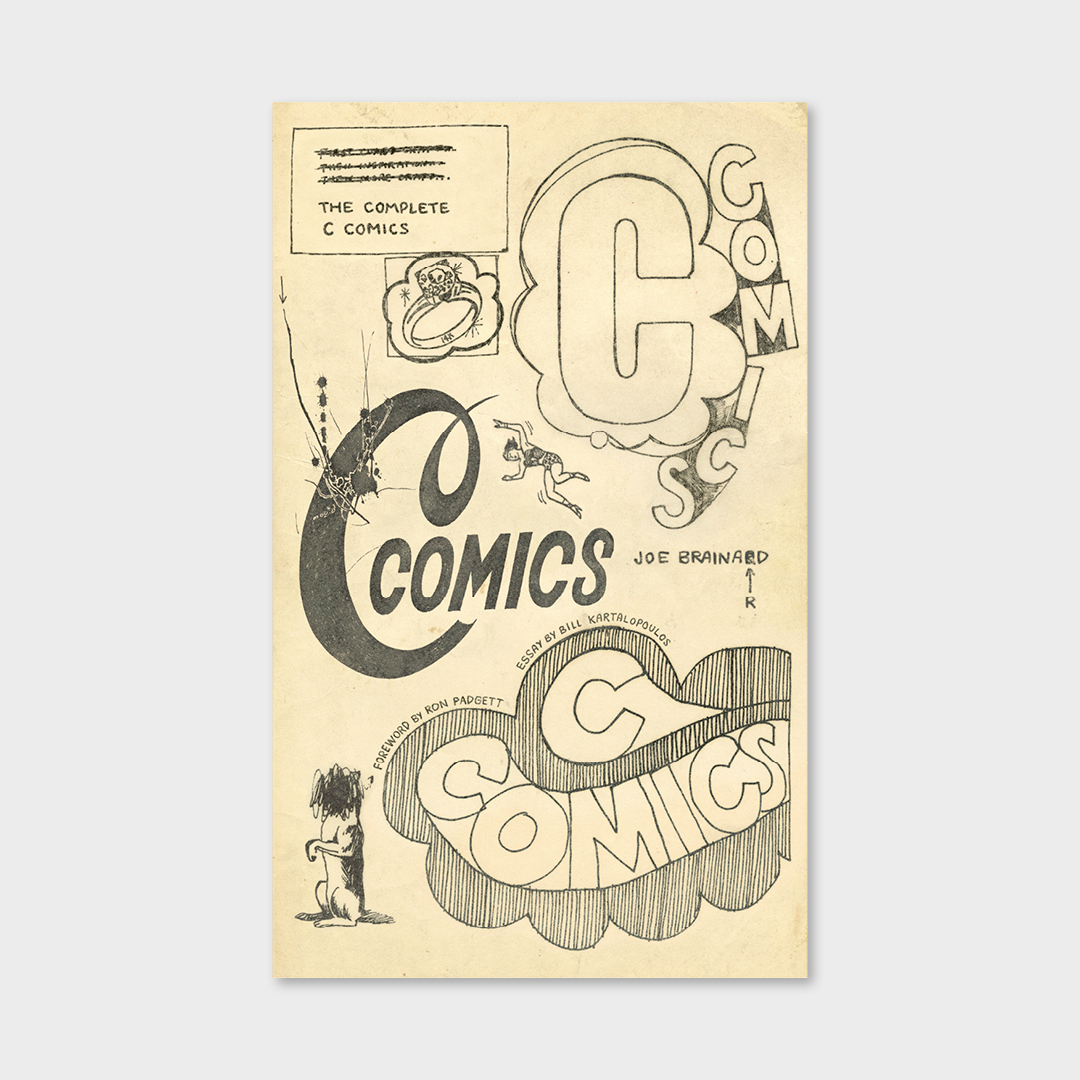

The Complete C Comics by Joe Brainard (New York Review Books)

Of all the art-world polymaths who came of age in 1960s New York, Joe Brainard was the most fun. Poet, painter, collagist, bookmaker and set designer, he seemed to approach every creation as a kind of lark, playing hide-and-go-seek with his intentions, which were as serious as those of any of his peers in the New York School. In 1964, at the age of twenty-two, he bounded with no prior experience into the comic-book world, starting C Comics as a place for his friends, among them Ron Padgett, Frank O’Hara, Anne Waldman, Barbara Guest and John Ashbery, to romp around with word and image. Copies of the series, which lasted only two issues, have long been rare and expensive. This marvelous facsimile compilation is introduced by Padgett, who remembers: “We did the work simply for the pleasure and adventure of it, with little or no thought of how it might be received by the public. Likewise, it was happily free of theoretical ambitions, such as toward being avant-garde or radical or even funny.” Brainard’s beloved Nancy, from Ernie Bushmiller’s comic strip, shows up in both issues, at one point observing sagely: “Though they work by instinct, bees (like humans) seem happiest when deeply involved in a project.”

—Randy Kennedy

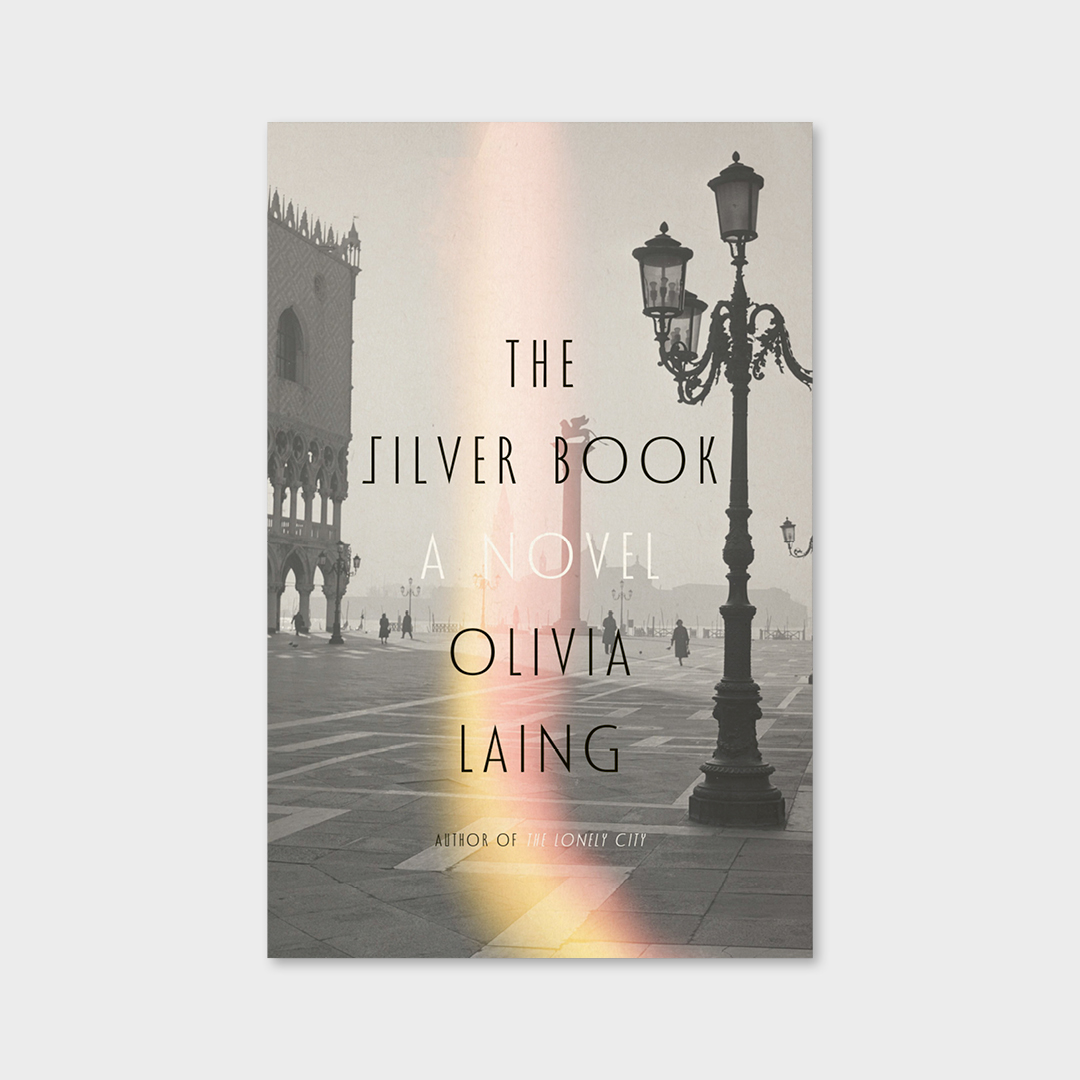

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing (Farrar, Straus and Giroux – US release)

In autumn 1974, as political unrest flares across Italy, two films of radical cinematic ambition are underway: Fellini’s opulent Casanova and Pasolini’s brutal Salò. Between them is Nicholas Wade, a young British artist who has recently fled London under suspect circumstances. After arriving in Venice, he is taken on as an apprentice to Danilo Donati, the real-life set designer for both productions, here fictionalized as a mercurial and magnetic creative force.

What begins as a sensuous travelogue becomes something deeper and more fractured. The men’s alternating seductions escalate into a power struggle fueled by desire. Shadowed by the 1975 murder of Pasolini, The Silver Book moves with historical fidelity through a world of glittering excess—Rome’s cavernous Cinecittà studios, Pasolini’s red Alfa Romeo GT, Donald Sutherland’s gold-threaded costumes—and also exposes the flimsy façades of moviemaking. The surfaces shimmer, but Laing’s interest lies beneath, in betrayal and evasion. With taut control, they build a mesmerizing and devastating study in which identity itself is a kind of set dressing—ever shifting and dangerously easy to dismantle.

—Alexandra Vargo

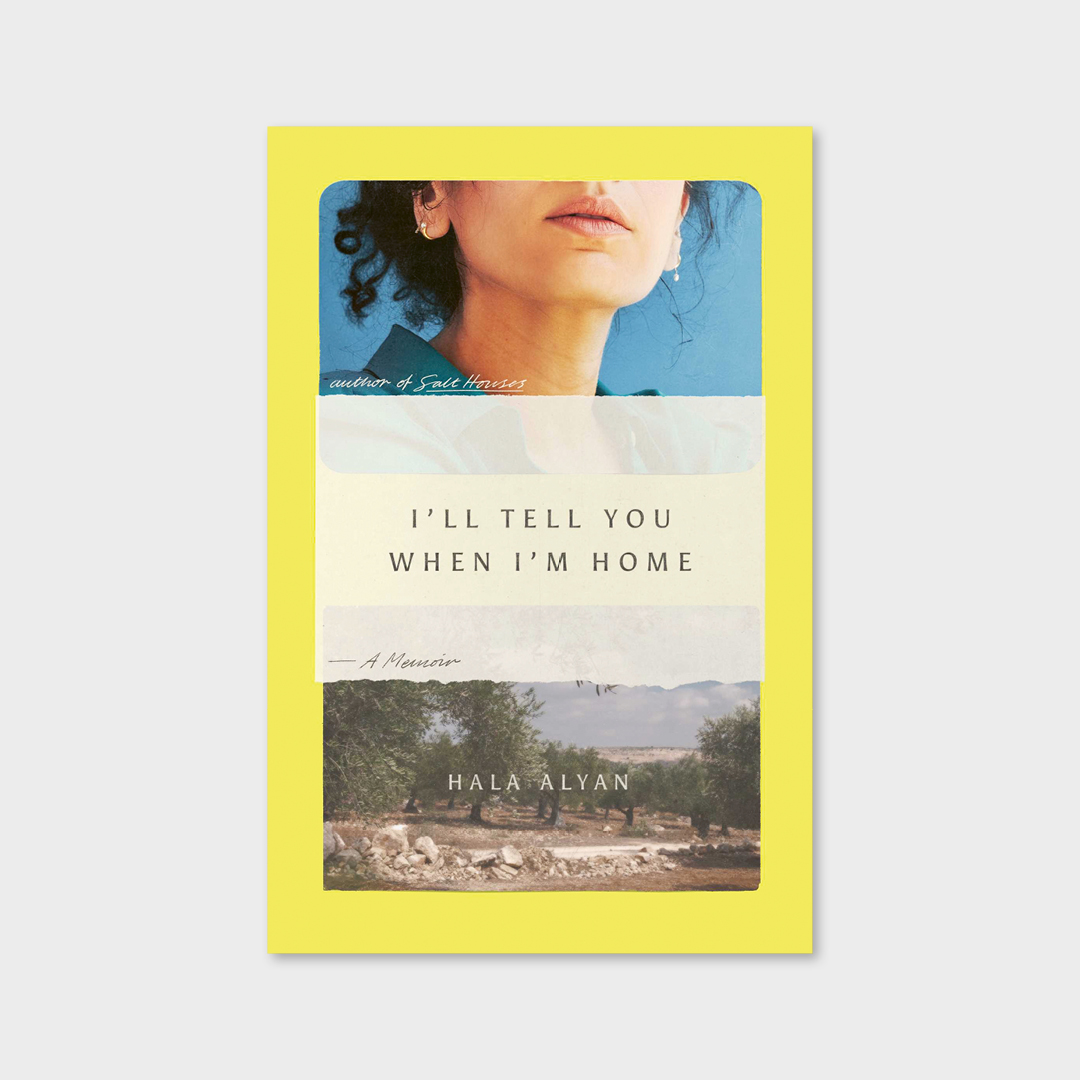

I’ll Tell You When I’m Home by Hala Alyan (Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster)

“There was and how much there was,” Palestinian poet Hala Alyan writes in her new memoir. The literal translation of the Arabic kan yama kan, the phrase is often rendered in English as “once upon a time.” The two expressions remind me of fraternal twins—connected but different.

When we enter her story, Alyan is living in New York City with her American husband. After several miscarriages, their baby is finally growing—from the size of a grain of rice to a raspberry, a lime, an avocado, a coconut—in the belly of a woman in Canada. While we wait, Alyan recounts her life, inextricable from the lives of others, in broken-up stories revealed as masterfully as the mythic tales of Scheherazade, who evaded death by rendering her husband-killer helpless with cliffhangers.

We learn about her grandmothers, now photographs she consults like Magic 8 Balls; her alcohol-powered youth in Beirut; “the heave of the earth” she can feel in America while her homeland is split by the “teeth” of bulldozers, bombs. The reading experience is faith-based, compulsory. You want to know that the fragments of her life stories will culminate and combine with others and go on like her now-this-size-fruit baby in that unlikely womb. (I won’t tell you if they do.)

—Jana Horn

Louise Bourgeois: Insomnia Drawings, Limited Edition. Text by Marie-Laure Bernadac and Elisabeth Bronfen (Hauser & Wirth Publishers)

“The drawings of the night,” Louise Bourgeois writes, are littered with semi- coherent notes to self. “I love you because you make me feel important”; “Not homeless but armless, do you see the mosquitoes”; “Pourquoi le hérissons’ hérisse-t-il? (Why does the hedgehog bristle?)” These are the unfettered thoughts of a mind in need of sleep.

Bourgeois’s Insomnia Drawings are filled with intrusive thoughts and apparitions, manic gestures and composed landscapes. Scrawled on whatever paper she had at hand, the 220 works she made between 1994 and 1995 feature an abundance of tightly recurring marks that form and unfurl. Part notation, part poetry, part Freudian-style record-keeping, the texts annotating these drawings have a captivating immediacy. The minutiae of never ending to-do lists collide with lyrical lines and critical reflections.

Originally published in 2001 and made newly available by the Easton Foundation and Hauser & Wirth, this two-volume publication reproduces the drawings in one book, and in the other offers incisive essays to accompany full transcriptions of Bourgeois’s writings in French and English. It’s a welcome companion for one’s own sleepless nights.

—Alexis Lowry

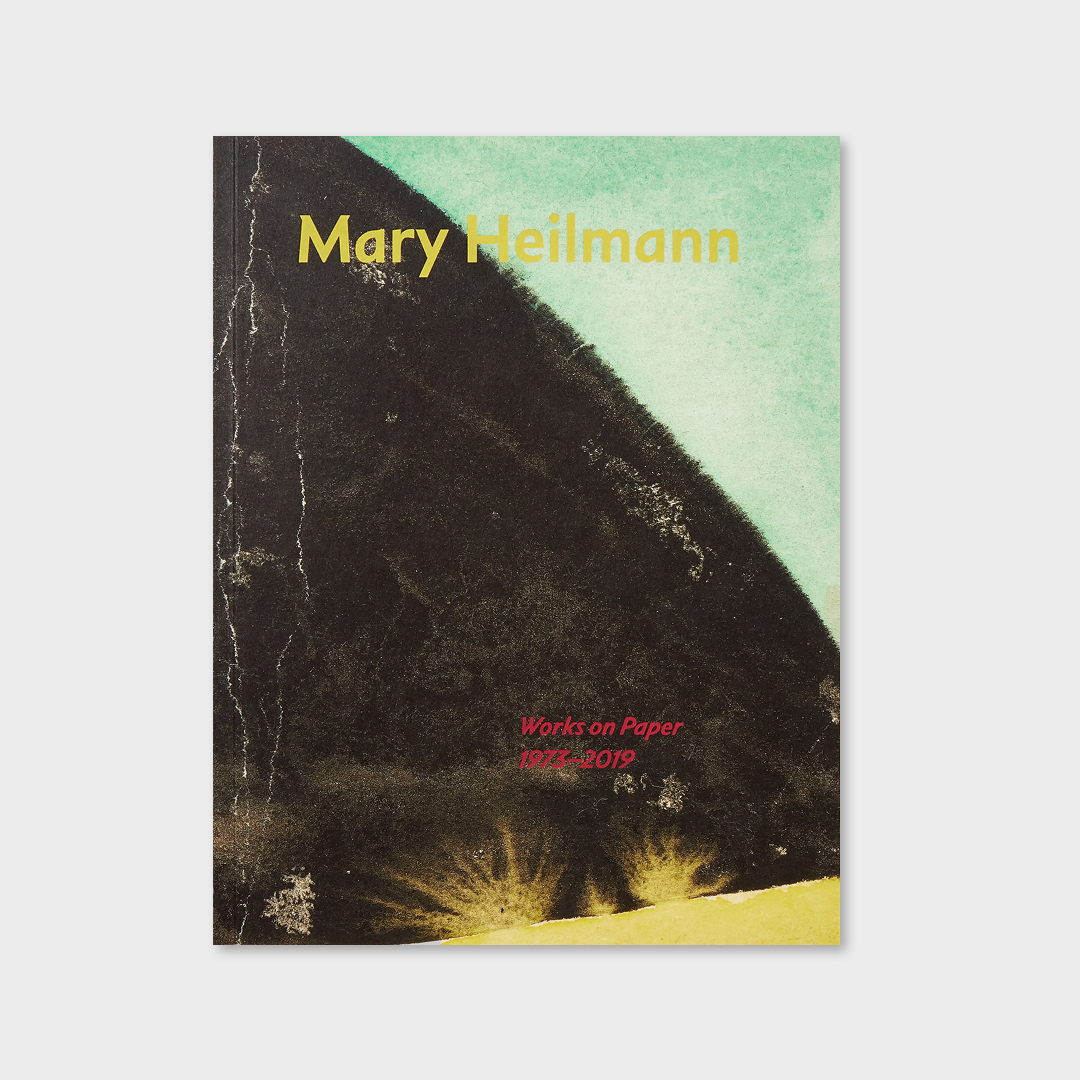

Mary Heilmann: Works on Paper, 1973–2019. Edited and introduced by Alexis Lowry Text by Jo Applin and Ilana Savdie (Hauser & Wirth Publishers)

This is the first book of its kind dedicated solely to Heilmann’s little-known work on paper, which builds on her 2024 exhibition “Daydream Nation,” curated by artist Gary Simmons.

Throughout this collection are recognizable elements of Heilmann’s visual language—her bold color palette and abstract compositions—alongside surprises, including rare examples of figuration and handmade paper pieces verging on sculpture. The works range from intimate watercolors and pulp constructions to layered acrylic pieces, all infused with Heilmann’s fearless mark-making and the sensual immediacy unique to paper. Trained as a sculptor and ceramicist yet known primarily as a painter, she treats paper as both surface and object by engaging the edges and creating constructions.

Edited, and with an introduction by, curator Alexis Lowry, Works on Paper also offers a personal reflection from artist Ilana Savdie and an essay by art historian Jo Applin linking Heilmann’s paper works to her broader oeuvre. Altogether, the elements here celebrate the delicate, sculptural and serious yet playful spirit that has defined Heilmann’s throughout her career.

—Melanie Crader

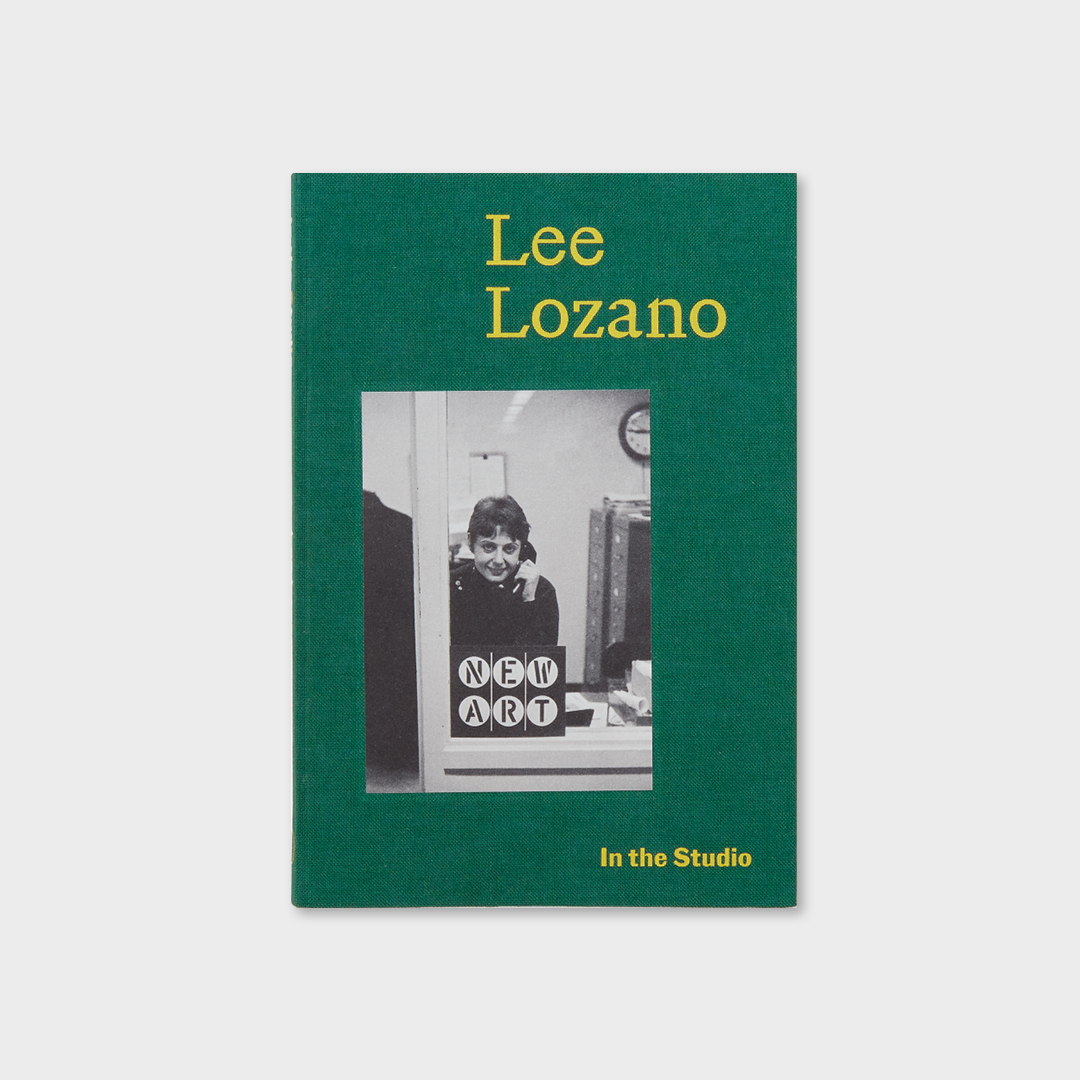

In The Studio: Lee Lozano. Text by Lucrezia Calabrò Visconti (Hauser & Wirth Publishers)

Navigating the crisscrossing currents of the heady New York art scene in her time, Lee Lozano burned bright and flamed out, leaving an indelible slipstream of ash in the art historical record. From 1960 to 1972, her work evolved quickly, from loose, raunchy figuration to illusionistic paintings to saturated geometric abstractions that reached their apotheosis in her monumental Wave series—a group of eleven paintings grounded in a quasi-scientific investigation of the electromagnetic spectrum. The three-year process of creating those paintings galvanized a final shift into working directly with behavior, energy, language and personal experience, making her, as Lucy Lippard later wrote, the major female figure in Conceptual art at the time. Phew!

Lucrezia Calabrò Visconti, a co-curator of the 2023 retrospective “Lee Lozano: Strike” at Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin, delivers a well-researched and cohesive overview introducing this singularly intense artist—whose “Life-Art” project culminated in Lozano’s boycott of women and her disappearance from the art world at the peak of her career. With generous color illustrations, a practical chronology at the back and brief thematic chapters, this third installment of the In the Studio series is a breezy afternoon read that just might blow your mind.

—Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer