Diary

A Veritable Voyage

Beverley Calté on the life of Olga Picabia (1905–2002)

Olga Mohler Picabia and Beverley Calté at “Francis Picabia: Das Spätwerk, 1933–1953,” Deichtorhallen Hamburg, 1997. Courtesy Archives Comité Picabia, Paris

On the occasion of a major Francis Picabia exhibition currently on view at Hauser & Wirth New York’s 22nd Street location, Ursula spoke with Beverley Calté, a curator of the show and president of the Comité Picabia, who shared her memories of Olga Mohler Picabia, the artist’s last wife.

Born into a modest family in Rubigen, Switzerland, in 1905, Olga Mohler studied to be a kindergarten teacher. At the age of twenty, she found a position in Mougins as governess for Lorenzo, the five-year-old son of Picabia and Germaine Everling. In the home they called the Château de Mai, Olga became an indispensable part of their household, not only for young Lorenzo but for his father as well. Among her many jobs, she cleaned Picabia’s paintbrushes, stretched his canvases, tended to his wardrobe and soon became his constant, compassionate travel companion. Following a visit to Barcelona in 1927, an amorous liaison began.

While artistic expression was Picabia’s vital necessity, he also had a particular passion for automobiles and a singular attraction to women. He married Gabrielle Buffet in 1909. They parted ways in 1919, after Germaine came into his life. She was his companion until their rupture in 1933, but both Gabrielle and Germaine continued to play important roles for Picabia.

Pierre Calté and Olga in Rubigen, Switzerland, 1979. Courtesy Archives Comité Picabia, Paris

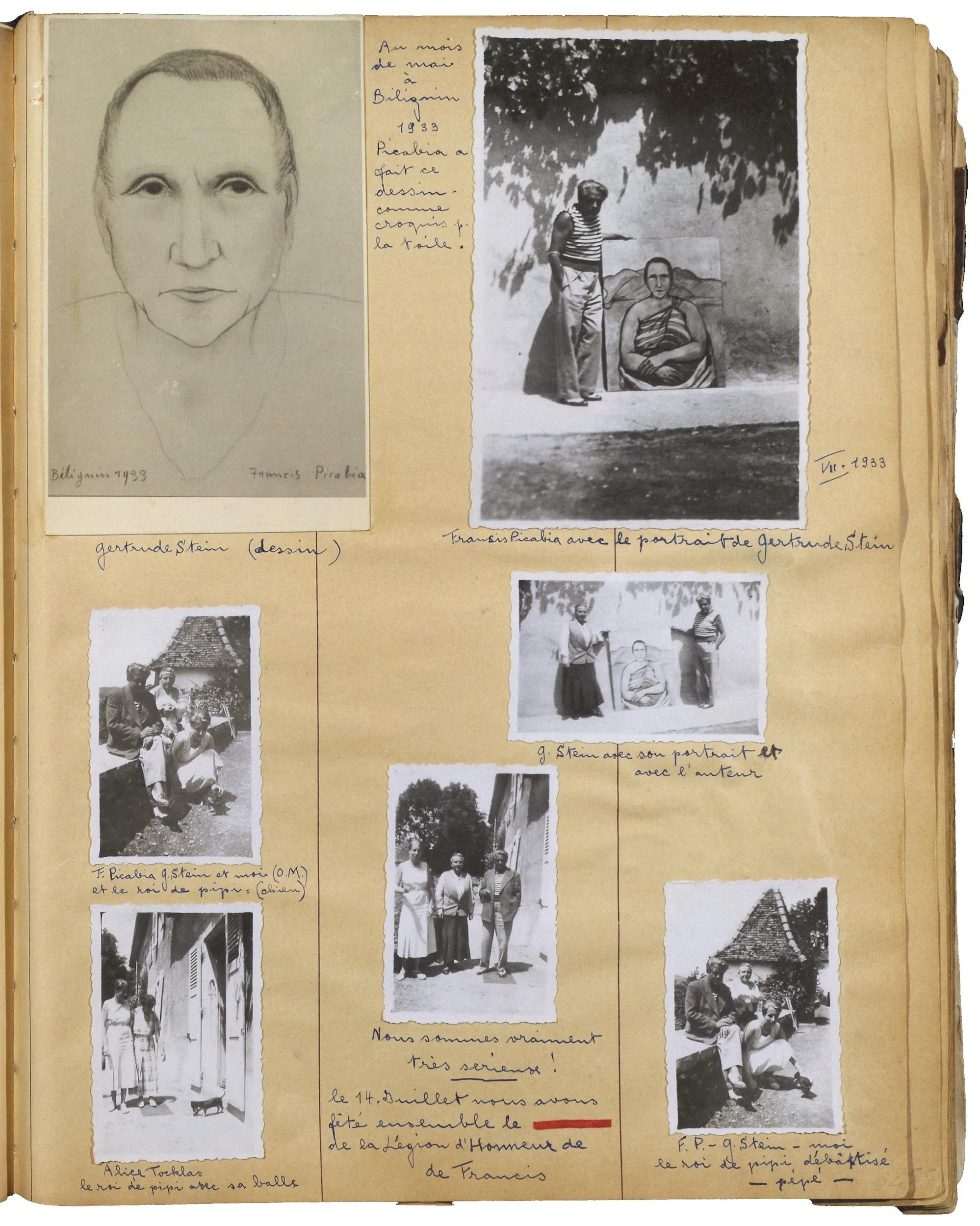

Olga became Picabia’s protégé and succeeded in living up to her mentor’s great expectations. At first, she existed somewhat in the shadow of the artist’s world that evolved through Picabia’s invaluable friendship with Gertrude Stein and her partner Alice B. Toklas. Gertrude and Alice adored Olga, and she loved to visit them at their home in Billignin, France. In her native Switzerland, her relationship with Meret Oppenheim was also very important to her. On the other hand, she was afraid of Picasso, saying he had a look that could burn a hole in your skin!

Before leaving the Château de Mai, Olga collected every memento she could find from the drawers in the house and studio. In 1936, four years before her marriage to Picabia, she began work on an album in a rented flat on the Bois de Boulogne during one of their trips to Paris. The album expanded, with innumerable letters, drawings, press clippings, exhibition invitations and photographs, including some from Picabia’s childhood. She accentuated these with personal annotations, which Picabia described as her “grandiose book of poems.”

Olga stopped work on the album in late 1952, eight years after she and Picabia returned to his Paris atelier. When he had difficulty walking, she helped him to sit in front of the terrace windows and read him excerpts from books by his “alter ego,” Nietzsche. Picabia once said, “My paintings are a reflection of my life.” The album exists as a remarkable reflection of Olga’s dedication to Picabia. Her life was a veritable voyage. Her dauntless devotion to Picabia is somewhat comparable to his constant, undaunted change of artistic direction. After his death in 1953, she spent the rest of her life working to preserve his legacy.

Studio photograph of Olga with Le brave (The Brave) and her album, 1990s. Francis Picabia © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Courtesy Archives Comité Picabia, Paris

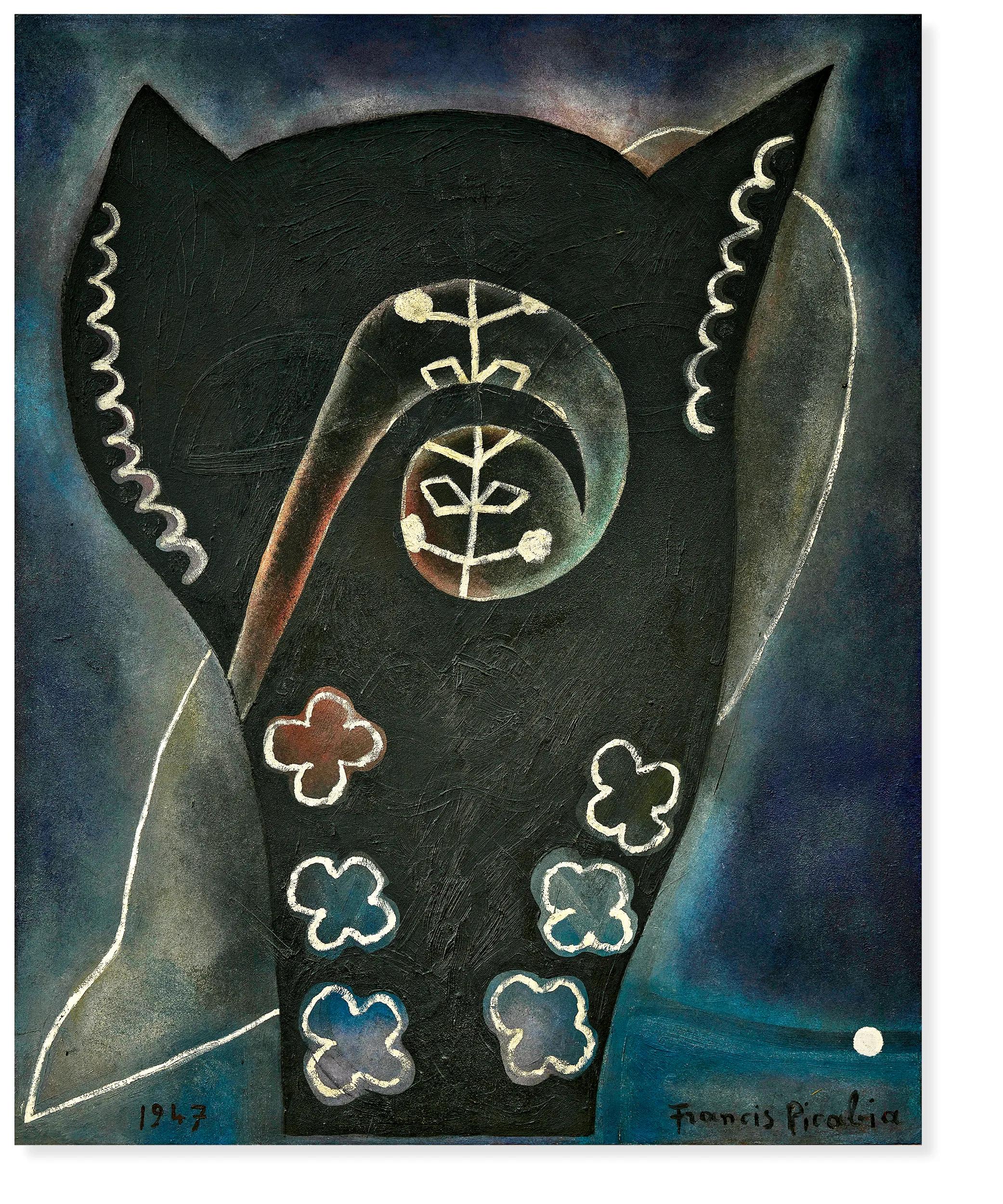

Francis Picabia, Le brave (The Brave), 1947. Oil on cardboard, 39 3/8 x 31 1/2 in. Francis Picabia © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Courtesy Archives Comité Picabia, Paris

In 1979, I met Olga with my late husband, Pierre Calté. That year, we had the chance to organize a Picabia exhibition at the Palais des Congrès in Paris, and through the introduction of a friend, we went to visit her in Rubigen. Olga was a programmatic Swiss woman who took to Pierre immediately. There was something about his spirit of freedom and adventure that reminded her of Picabia. She said, “Oh, you’ll never be able to do an exhibition in three months,” but we did it! For the next ten years, we traveled all over the world with her. She was seventy-five then, and we were like family. She and Pierre used to play chess together whenever we were traveling.

In Paris, Olga retained many works that Picabia painted after 1945, especially the nonfigurative paintings that were present on the walls of his atelier. It was on the fourth floor of the family-owned building where he was born and where they had returned in 1945. After inheriting the building, Picabia had to sell it during the war, but he managed to keep the atelier, and Olga continued to occupy it after his death. In 1990, Olga, along with Pierre and myself, established the nonprofit Comité Picabia in the atelier, a stone’s throw from the Place Vendôme.

Until the very end, Olga talked about Picabia as though she had seen him just that morning. She called him a prince and one of the world’s truly original artists. Since her death in 2002, the Comité has had the honor of continuing to occupy this space, whose history remains forever present.

My wish is to digitize our extensive archives and make them accessible to the public so that when I’m off to see Olga and Pierre playing chess somewhere in this vast universe, the Picabia atelier will carry on as a place of study.

—As told to Alexandra Vargo

Page from an album devoted to Francis Picabia’s life and work, compiled by Olga Mohler Picabia. Courtesy Archives Comité Picabia, Paris. A selection of pages from the original album is published in Olga Mohler Picabia, Album Picabia, ed. Beverley Calté (Brussels: Mercatorfonds, 2016)

–

"Francis Picabia: Éternel recommencement / Eternal Beginning,” curated by Beverley Calté and Arnauld Pierre, remains on view at Hauser & Wirth New York’s 22nd Street location through August 1.

Francis Picabia: Éternel recommencement / Eternal Beginning is now available from Hauser & Wirth Publishers. This dual-language catalogue includes texts by Beverley Calté, Arnauld Pierre and Candace Clements, plus a selection of pages from Olga Picabia’s album.

Beverley Calté is an independent scholar and a co-author of the four-volume Picabia catalogue raisonné (Mercatorfonds, 2014–22). In 1990, she and Pierre Calté were chosen by Olga Picabia to found, along with William and Virginia Camfield, the Comité Picabia in Paris, of which she is the current president.