Essays

Arrivals and Departures

Felix Petty on the existential spirals of Brian Eno’s Music for Airports

Untitled (Tokyo I), 1990. C-print, Edition of 6 + 1 AP, 48 3/4 × 72 3/4 in. Courtesy Estate Peter Fischli David Weiss and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / Vienna © Archiv Peter Fischli David Weiss. Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography, Zürich

Fifty years ago, in January 1975, Brian Eno was hit by a taxi after leaving a recording session in London. He was hurt so badly that passersby thought he was dead. After a hospital stay, he found himself back at home, bedbound and recuperating. A visiting friend left a record of 18th century harp music playing for him, but the volume on the stereo was too low and Eno, unable to get out of bed and turn it up, instead had to let it play on gently.

Half-conscious and dosed up on painkillers, Eno heard the music blend into and become indistinguishable from the sounds of the world around him, mixing with raindrops and traffic. The experience suggested to him a new way of hearing music, music as an intrinsic part of our surroundings, music as an “iceberg,” as he said in an interview with the NME in 1977—only partly visible, both made of water and also separate from it, adrift upon it.

A few years later at the Cologne Bonn Airport, afraid of flying and agitated by the restless atmosphere, Eno thought of an idea for background music that could prepare one for the death that awaited if a plane crashed: a kind of Muzak to guide you into the heavens, 38,000 feet up, a serene choir playing out through the sunshine over the top of the clouds as you approached the pearly gates.

Untitled (Frankfurt/Condor), 1998. C-print, Edition of 6 + 1 AP, 47 1/4 × 70 7/8 in. Courtesy Estate Peter Fischli David Weiss and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / Vienna © Archiv Peter Fischli David Weiss. Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography, Zürich

Peter Fischli and David Weiss, Untitled (Paris/Aeroflot), 1990. C-print, Edition of 6 + 1 AP, 47 × 70 3/4 in. Courtesy Estate Peter Fischli David Weiss and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / Vienna © Archiv Peter Fischli David Weiss. Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography, Zürich

Through these small but cumulative epiphanies, which occurred somewhere between heightened emotion and incapacity, Eno conceived of what he called ambient music, a genre that began as an avant-garde sonic expression of intense almost not-listening. It is music that places primacy on atmosphere—hence ambience, the character and atmosphere of a place—over rhythm or melody, favoring gentleness, modulation, repetition, subtlety and organic musical structures.

Though it arose from a very specific context and as a development of many other strains of experimental composition, it was defined more by a sensibility than a specific style, and its amorphousness allowed it to spread and adapt into many other genres, from chill-out techno to drone metal.

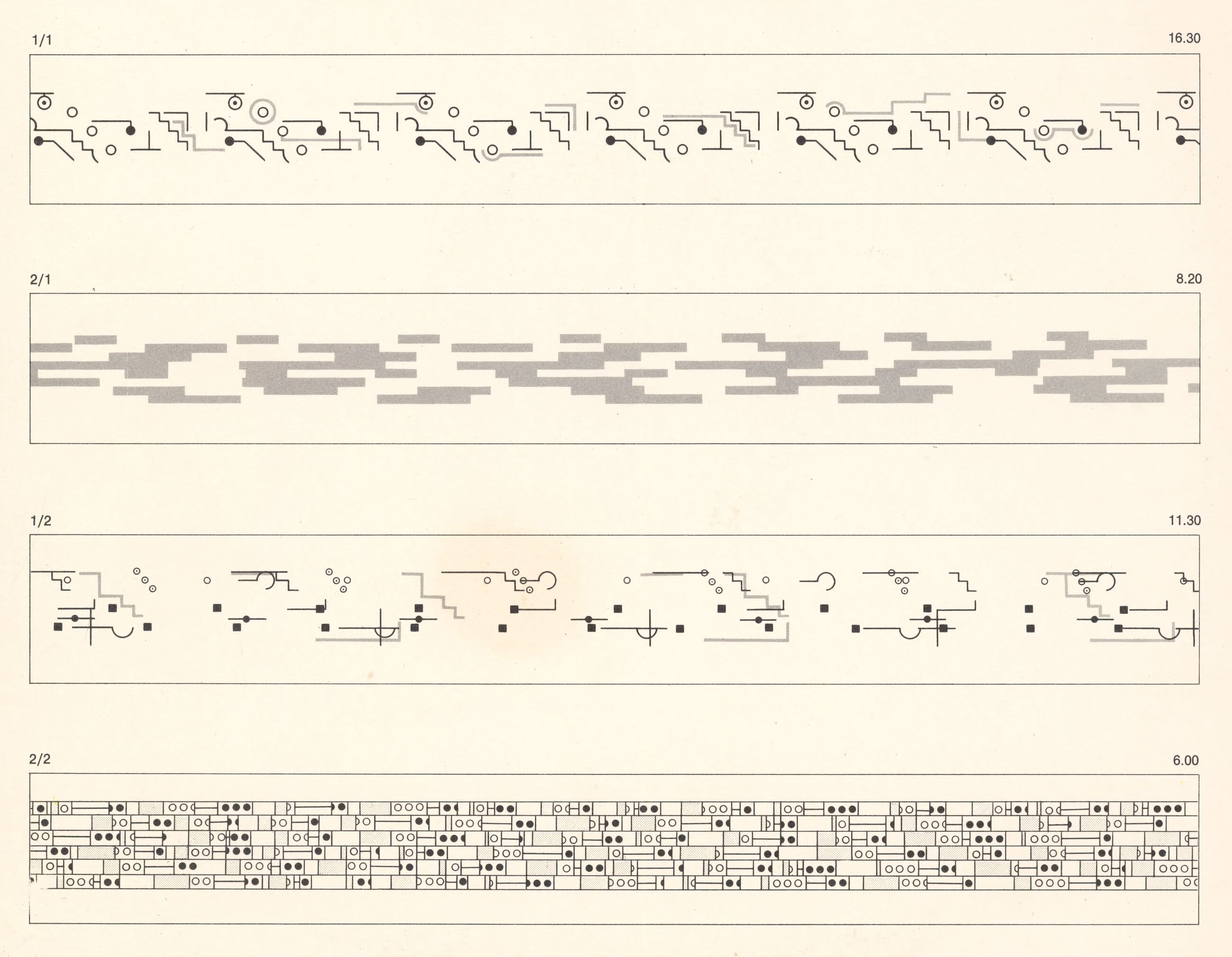

Recently, while my brain was turned to standby as I scrolled through the endless images on my phone, I was surprised to be served, amid the social-media slop—and what is this slop but a kind of anti-ambient music, designed to hijack attention and presence—with an image that made me actually think: the score Brian Eno had created for his landmark 1978 album Ambient 1: Music for Airports.

At first glance I took the image to be a piece of abstract art rather than musical notation. There was something beautiful and intriguing about it, floating visually somewhere between Mondrian and Agnes Martin. I had listened to Music for Airports for so many years, but the music had always been mediated by the disembodied interface of Spotify, so I’d never previously come across the score, tucked away as it had been in the physical world of a vinyl record or CD case.

A classical score exists before a piece is played and is an intrinsic part of the composition itself. It is traditionally a set of detailed instructions for the assembly of a piece of music—two good violinists, for example, following a classical score, should be able to transform what is on the sheet into music more or less identically.

The score for Music for Airports is, by contrast, something closer to documentation, created after the composition. It is visual and sensory in addition to being instruction. In other words, the map is not the territory.

The effect of listening to Music For Airports … is of experiencing something almost like absence, an elegy for music, music haunting itself.

As I looked at the score, I was instantly able to recall and recognize the rhythms, cadences and tempos of Music for Airports in the same way I might recognize the original French of a poem by Rimbaud that I know intimately but only in translation.

There in the slop, a neat full-circle moment occurred for me in my experience with the album and the quality of the attention I paid to it. This made sense. Ambient music, after all, began as a kind of anti-Muzak. Whereas Muzak serves as lightweight background music, ambient music, in Eno’s conception, focuses precisely on the spatiality of what makes up a “background,” music as an architectural structure, giving space for thought within the physical spaces we inhabit.

If ambient music is environmental, it is so in a Borgesian sense—looping and endless. It is system music, generative and self-fulfilling. The score reflects this. It gets to the emotional heart of Music for Airports in ways that traditional notation cannot.

“Whereas conventional background music is produced by stripping away all sense of doubt and uncertainty from the music, Ambient Music retains these qualities,” Eno wrote in the album’s liner notes. “And whereas [Muzak’s] intention is to ‘brighten’ the environment by adding stimulus to it, thus supposedly alleviating the tedium of routine tasks and levelling out the natural ups and downs of the body’s rhythms, Ambient Music is intended to induce calm and a space to think.”

Ambient’s antecedents stretch back to Erik Satie’s early 20th-century idea of “furniture music”—pieces that he composed to score lunch or dinner, the arrival of guests, the interludes in an evening’s entertainment. It was an idea later picked up by John Cage in his conception of minimalist music, most famously his piece 4’33”, which was all background—four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence, the only sounds being those of the audience, shuffling or coughing, or the noise filtering in from outside.

Eno rose to fame playing synthesizer on the first two Roxy Music albums, but after leaving the group he began working in a more experimental fashion. His compositions with Robert Fripp in the ’70s explored the possibility of tape loops in music-making and became known as Frippertronics. Two reel-to-reel tape recorders would be set up side by side, and sounds recorded on the first deck—here, specifically, Fripp’s guitar—would be played back onto the second deck, then routed back into the first deck to create a long, looping delay. One input creates an infinite and constantly evolving piece of music.

Another important precedent in discussing the score for Music for Airports is Eno’s pre-Roxy affiliation with Cornelius Cardew and his Scratch Orchestra, which used amateur musicians, and also, importantly, nontraditional graphical scores to allow the musicians to play together without prior knowledge of classical notation. The “score” for Cardew’s The Great Learning, a project in which Eno had a hand, is simply a set of written instructions that resembles something like a Fluxus artwork. In his 1976 essay, “Generating and Organizing Variety in the Arts,” Eno reflects on this, suggesting a musical score as simply “a statement about organization . . . a set of devices for organizing behaviour toward producing sound.”

Graphic score included in the liner notes for Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports (1978), released by Polydor in 1979

These musical strands of Eno’s were deepened during the 1970s through his involvement in the German Kosmische Musik (Cosmic Music) scene, where he participated as a producer and composer on technological experiments, released two albums with the band Cluster and spent time in Berlin with David Bowie. The scene’s approach to electronic sound production was propelled by the invention and development of the synthesizer, which led to the creation of a totally new, inorganic sound.

The effect of listening to Music for Airports—and Discreet Music, Eno’s first experiment in ambient music-making, released in 1975—is of experiencing something almost like absence, an elegy for music, music haunting itself. The recordings reach toward something deep in music’s historical purpose—whether that be ritual or dance or virtuosic performance or salon entertainment—while also pushing into something beyond music.

The aim, Eno wrote in the Music for Airports liner notes, was to create music “as ignorable as it was interesting,” a line that has become perhaps his most widely quoted. There’s a sadness to the idea. The result is almost too beautiful. But at the same time the sounds seem to fade into nothingness—a strand of the ambient sensibility that would later be explored more deeply by figures like the composer William Basinski and the electronic musician William Emmanuel Bevan (better known by his musical alias, Burial), both of whom make music that feels explicitly haunted. One thinks of Burial’s inclusion of tape hiss and vinyl crackle on otherwise wholly digital recordings. Or of Eno’s tape-loop system playing back some old cassettes. For a true sense of the spectral nature of such work, consider the image of tapes disintegrating slowly with each whirl around the recording equipment in Basinski’s Brooklyn loft as he watches two airliners crash into the World Trade Center. (Basinksi finished his venerated The Disintegration Loops on the day of the 9/11 attacks, another link to the existential dread of air travel.)

Like Music for Airports’ generative endless loops, the genre aims to create work that involves human input but that ends up somewhere beyond human control—or that suggests the presence of the human operating from within the machine. The individual pieces of music that make up Music for Airports are built from a series of loops that could play out infinitely without repetition despite the endless repeating of the individual loops.

Ambient music shares structure with human intelligence, at least in the way that Jung conceived of human experience, “Psychologically, you develop in a spiral,” Jung wrote. “You always come over the same point where you have been before, but it is never exactly the same. It is either above or below. A patient will say, ‘I am just at the place where I was three years ago,’ but I say, ‘At least you have travelled three years.’ ” This structure is reflected in the details of the scores, which have, at first glance, an overriding structure but never align in the same way.

In a 1986 lecture in San Francisco, Eno said: “All of my ambient music . . . was based on . . . the idea that it’s possible to think of a system or a set of rules which, once set in motion, will create music for you.” To read the score for Music for Airports is to read not simply inputs for specific notes or instruments but to read a representation of a system. Each mark can be read as what might be put into that system.

At least in the way that Jung conceived of human experience, ambient music shares structure with human intelligence. “Psychologically, you develop in a spiral,” Jung wrote. “You always come over the same point where you have been before.”

In the score for track “1/1” on the album, a sequence of repeated notations appear to correlate to something: a straight line that later descends like stairs; three circles, also descending; an upside-down T, ascending. Attempting to follow a piece of music with these types of graphic notations not only leaves space for the user to think but also demands thinking. What instrument might the circle represent? What is the starting note? Should all the lines be the same instrument? What is the tempo, the key, the time signature?

The notation for track “2/1” is even more minimal—just a series of gray bars of different lengths arranged over eight rows. A certain logic must be followed, but the rest is open-ended—the space between the notes and the duration, the tone, the instruments.

In his 1995 essay “Generic City,” Rem Koolhaas cites the airport as the supreme building of the modern world. It is, he suggests, a replacement city, a place of endless hyperglobal sameness and hyperlocal variation. It is also a loop, a hermetically sealed system. We travel from airport to airport and back again. Despite the variety of architectural styles, each airport is essentially the same. Eno’s score works much the same way. It is notation as a Möbius strip. Though it travels, it always ends up where it began, almost.

Writing about his inspiration for Another Green World, also released in 1975, Eno explained part of his thought process: “I read a science fiction story a long time ago where these people are exploring space and they finally find this habitable planet—and it turns out to be identical to Earth in every detail. And I thought that was the supreme irony: that they’d originally left to find something better and arrived at exactly the same place. Which is how I feel about myself. I’m always trying to project myself at a tangent and always seem to eventually arrive back at the same place. It’s a loop.”

Music for Airports is about the small, beautiful epiphanies that occur somewhere between consciousness and death, in the sky. It approaches the sublime, a rare achievement for a piece of purely mechanical art. It’s about the human response to the natural, about the beauty that is produced by the accidental. It asks what instrument a circle represents and about the duration of a gray line.

–

Felix Petty is a writer and editor based in London. Previously editor of i-D magazine, he is currently head of content at Kaleidoscope. He has written for Fantastic Man, Harper’s Bazaar, Marfa Journal and The Spectator.