Essays

Acts of Senseless Beauty

The Exquisite Corpus of Babs Santini

Bob Nickas on the art and music of Steven Stapleton and Nurse With Wound

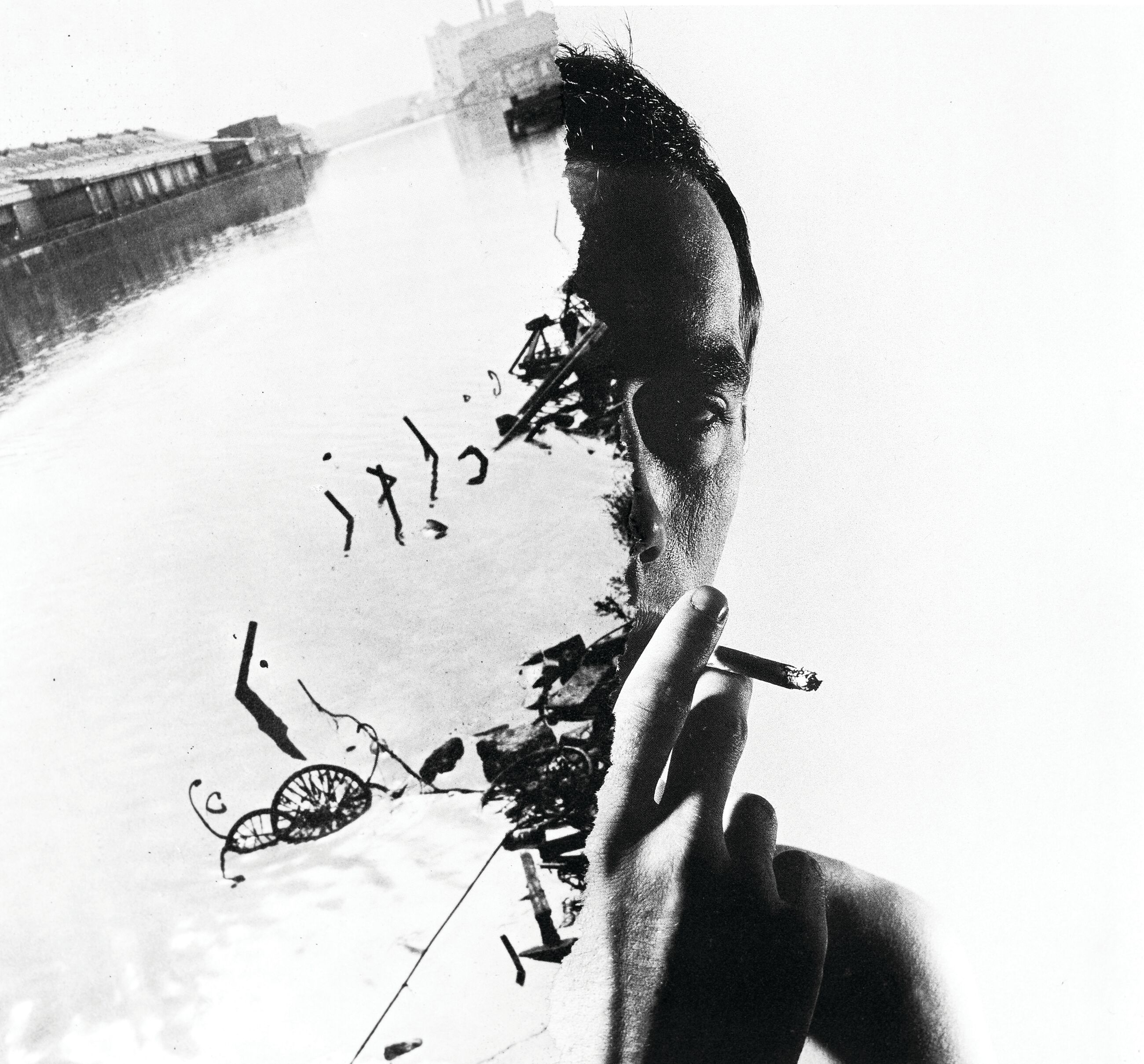

Cover of Nurse With Wound’s Thunder Perfect Mind, 1992

John Heartfield, Hannah Höch, Max Ernst, Kurt Schwitters, Roland Topor, Bruce Conner, Babs Santini … [short pause] Babs Santini? You must be wondering, surely, how it is that a list of key figures in Dada and Surrealism, artists who wielded, as a weapon, some of the most incisive political imagery ever imagined and who helped to map the undulating contours of a major 20th-century movement, conclude with a name we’ve never heard before. As if she is a long-lost heir to the great enchantment and derangement of decades prior. She is, very much so. But Babs Santini is not previously unknown or forgotten, some shadowy figure from the 1930s or ’40s rediscovered only now. No, if the name is wholly unfamiliar this is completely understandable because Santini, an elusive figure from the present, doesn’t actually exist except in the febrile mind of our greatest living Dada and Surrealist, the British musician Steven Stapleton.

Far off in the ancient days of 1978, although he couldn’t have predicted it at the time, Stapleton set out on what was to become a wildly adventurous musical project now spanning more than four decades and counting, the highly regarded Nurse With Wound. Under this indelible name, the band has released well over 125 albums, in addition to dozens of singles and special editions (keeping track of the ever-prolific Stapleton is no easy task), most of which feature artwork credited to Babs Santini, Stapleton’s female alter ego. While no images of Stapleton as Santini are known to exist, in the manner of Duchamp’s transformation into Rrose Sélavy, the two are in every way conjoined, boundless sensibilities—nothing is real, everything is possible—entwined with the work of fellow artists who have plumbed the dreamlike realms of the unreal.

This ongoing musical/visual alliance—characterized by Stapleton in a description worthy of the Surrealist manifesto as “acts of senseless beauty”—turns the world inside out, conducts an autopsic investigation, detourns perception. It is a hijacking of and a mischievous misuse of images and sound, an engagement that continues to heighten and offend the senses, delighting and disturbing in equal measure to this day. Stapleton’s ever-resonant motto for Nurse With Wound? “Purveyors of Sinister Whimsy to the Wretched.”

“A world as fractured as ours … requires the kind of dissection and stitching together implicit in the very notion of montage, evocative of moving rather than still pictures.”

Where did it all begin? With a hooded, black-leather-clad, bare-chested dominatrix, cat o’ ninetails in hand, looming over the cover of the first Nurse album, 1979’s Chance Meeting On A Dissecting Table Of A Sewing Machine and An Umbrella. With the title, by way of Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror, animating the group’s name and the image, the cover proved so provocative that some shops would carry it only in a plain brown wrapper—censored, arousing even greater curiosity. While the image remains unsettling for some, just as the music contained on the record does, for others there was and remains an immediate attraction. The old adage that you can’t judge a book by its cover likely means little or nothing to Stapleton, for whom a cover can function alternately as warning and enticement: This is what you are about to get yourself into. He has remarked that when he was younger, he often bought records because of an undeniable pull elicited by the artwork, title or band’s name. In the echoing visual/textual identity of Nurse, and in its fluidly shifting continuity over the years, Stapleton has provided similar enticement for subsequent generations.

That first album included an insert, the justly famous Nurse With Wound list, in which he and his cohort identified myriad influences and interests, and which, long before Internet algorithms, turned many onto recordings that wouldn’t have otherwise been discovered without significant delay, all sorts of obscurities yet to be encountered. For every recognizable name—John Cage, Can, Henri Chopin, Yoko Ono, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, La Monte Young—dozens simply hadn’t registered with us. How else would we know about Bladder Flask, Horrific Child, Lemon Kittens, the Nihilist Spasm Band, Taj Mahal Travelers, Álvaro Peña-Rojas (famous for his “singing nose”) and Xhol Caravan? The list is the document of experimental and avant-garde music. These influences were acknowledged from the start, although they required investigation. Nurse’s visual influences have been a longer study, appearing and evolving from one record to another.

Cover of Nurse With Wound’s The Surveillance Lounge, 2007

Babs Santini, Captains of Industry IV (The Creator), 2015. Montage work

Now, all these years on, Babs Santini finally gets her due with a monograph, The Formless Irregular, compiled and designed by Steven Stapleton, Sarah Stapleton and Andrew Thomas (Timeless Editions, 2025), a book of 500 pages, twelve years in the making. It makes abundantly clear that “the dissecting table” is not a location, no morbid slab of cold metallic furniture, but a freewheeling approach to visual material, liberally dosed with humor, absurdity and irreverence, propelled by a firm grasp of history, as well as world events and their horrible recurrence. After all, a world as fractured as ours, in perpetual motion, at times spinning out of control as it is today, requires the kind of dissection and stitching together implicit in the very notion of montage, evocative of moving rather than still pictures. A movie is a succession of images, twenty-four frames per second, seamlessly, or seemingly. The material is fragile. What happens when film breaks in the projector? When the illusion has shattered but the machine keeps running? Just as in life. Stapleton prefers the term “montage” over “collage,” conjuring filmic language, its cutting, splicing and editing, and this preference applies in equal measure to his visual and musical realms, where accident may be welcome.

A parallel can be drawn to experimental literature, most obviously the cut-up method of writing developed by Brion Gysin in the late 1950s, shared with and explored by William S. Burroughs. Other writers of speculative fiction hover in and around the Santini images, in relation to Nurse and its reverberating auditory chambers: J.G. Ballard with his book of linked short stories The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), which includes, notoriously, “The Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Considered as a Downhill Motor Race” and his novel Crash (1973). Orwell would have recognized the inconvenient truths implicit in the dystopia presented in Santini’s montages such as the 2015 artwork The Captains of Industry IV (The Creator), in which humans are subservient, cogs in a grinding machinery. (In black and white, there is little distinction between flesh and steel.)

“Stapleton’s soundscapes can be pictured in the mind’s eye as the soundtrack to any number of imagined movies, everything from ghost stories to slapstick comedy, from medical documentaries to ballets mécanique.”

These writers, disruptors and re-makers of reality, one and all, knew only too well that the world can explode in an instant. The cover of the 2018 CD version of Changez les Blockeurs is based on a photo of a mangled double-decker bus in London during the blitz, in the midst of collapsed buildings, rubble as visceral object-collage, with a face superimposed on the bus representing human wreckage—absent passenger fatalities. Elsewhere, images recur from Eisenstein’s iconic Odessa steps scene in Battleship Potemkin (1925). A large crowd of unarmed civilians, many women, children and the elderly among them, is dispassionately shot at by the tsar’s soldiers, as if at target practice—a scene all too easily aligned with our own time. Eisenstein focuses on a woman who, having been struck, crumples to the ground, losing her grip on a carriage with her baby inside. Teetering precariously on the steps, the carriage bounces down to an unseen, though likely tragic, end. Consciousness, space and time—collapsed as in a moment of trauma—are seen as a flip-book, fluttering in slow, chaotic motion.

Stapleton’s soundscapes can be pictured in the mind’s eye as the soundtrack to any number of imagined movies, everything from ghost stories to slapstick comedy, from medical documentaries to ballets mécanique. While we may be reminded inevitably of dream sequences from classic cinema as we encounter these montage works, they suggest nothing less than scenes composed entirely of such sequences—not only of dreams but also of nightmares. The Surrealists believed in automatic writing, a stepping outside oneself to attain other levels of creative connectivity: thought made audible instantaneously. Never mind that the trancelike poetry performed by Robert Desnos, for example, was mostly a parlor trick, his verse having been memorized. Here we can picture such a moment’s haute counterpart, Jean Béraud’s painting Le Monologue (1882), which depicts a well-dressed, rapt audience in a grand Parisian salon, seated before a well-known actor from the Comédie-Française. Santini’s transformation of the painting for the cover of the album Thunder Perfect Mind (1992), amounts to a hollowing out of all the eyes into skeletal black cavities. The now creaky actor is given an elongated, rubbery chin and his hair becomes wiry, spikes of fright (a finger poking an electric socket). High society is similarly spiked as grotesquerie. And what was the actor’s subject for the evening? Perhaps he held forth on the art of Babs Santini, how it evolved through the 1980s and into the ’90s from an ominous, primarily black-and-white palette into vivid, acidic color and psychedelic visions in the years following—drugs without having to take them. The actor would have noted how Stapleton had made drawings on LSD between ’85 and ’87, as Adrian Piper had twenty years prior, and created what he termed “phonautographic prints” to accompany the limited edition album Drunk With the Old Man of the Mountains (1987)—abstract/alchemical photos reminiscent of Sigmar Polke’s experimental camerawork. He certainly would have spoken of Polke along with Henri Michaux, both of whom took psychotropic drugs to heighten perception, when he presented Santini/Stapleton’s Psilocybin Great Teacher (2013), in which a figure from the Middle Ages hovers in hallucinatory space. He would have talked about Peter Hujar’s iconic 1981 portrait of David Wojnarowicz and its haunted reimagining for the cover of The Surveillance Lounge (2009). The subject of humor and irreverence would certainly have arisen, perfectly illustrated by Three Red Tears (2023), featuring, at its top left corner, the merged faces of Warhol’s Mao and Marilyn, with a whimsical adornment, a dangling hammer-and-sickle earring. He would have noted artists who have made “guest appearances” in these works, among them Man Ray and Carolee Schneemann, and provided context by relating the heady atmosphere of late ’70s British punk, bringing in Jamie Reid’s Situationist provocations and the great collagist Linder Sterling. The lecture would have been accompanied by excerpts from Spiral Insana (1986), The Ladies Home Tickler (1990) and Opium Cabaret (2020). This long but transporting evening might well have concluded with A Weird Surgical Indulgence (2023), our speaker wondering aloud, “Haven’t they all been?”

Babs Santini, Dream in Morse Code II, 2022. Montage work

Increasingly, since the pandemic and the rightward (wrongward) tilt in global politics, we have witnessed an unfortunate shift in art—from works with more seriousness of purpose to works of palliative escapism, art in which there is scant danger of disturbance. In this respect, Santini/Stapleton is an artist for our time. Upend things, he/she/they seem to be saying, and let’s see what lies beneath the surface—lies in this formulation suggesting deception. In this fraught moment, can we passively accept whatever is presented before us? Reality—all too often riddled with gaping holes as these works remind us, even when densely layered with information—is infinitely porous. Trust no one? Stapleton is consistently open to working with others. But his greatest collaboration may be the enduring one with himself these past forty-five years. In it we have the Surrealist drawing game of exquisite corpse, which involves at least two players and the sequential unfolding of an image built unexpectedly upon itself. Stapleton’s engagement with the game, conversely, is enacted by a single player, he alone, yet an element of surprise remains, for him first of all. In the twinned authorship of Santini/Stapleton, we confront an idea of split consciousness, the oscillating space in between, a split meant to be fused—patient/surgeon, anesthesia and sutures self-administered: Nurse With Wound.

–

Bob Nickas is a writer and curator based in New York. A new collection of his essays and interviews, Corrected Proofs: Previously Unpublished, Uncollected, Unwanted, was recently issued by At Last Books in Copenhagen.