Books

Eva Hesse’s Woodstock Paintings

by Gioia Timpanelli

Eva Hesse in her studio on the Bowery, New York, 1969 © The Estate of Eva Hesse / Münchner Stadtmuseum, Munich / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Hermann Landshoff

In the summer of 1969 Eva Hesse came to Woodstock, New York, with a small suitcase and a substantial box of drawing materials. The box was a green metal, no-nonsense toolbox filled with the ordinary number of artists’ brushes, some with flayed hairs, some intact—all had been through the paint wars. There were small bottles of ink, including silver and gold, a pristine Japanese inkstone and brush in a blue silk case with a bone clasp, stubs of colored pencils, a small hammer, razors, nails, and old tubes of favorite colors.

Eva stayed with her good friend the sculptor Grace Bakst Wapner and her family until Grace’s mother came to visit, then space was needed, so instead of going back to the City, Eva came to live with me in my old Byrdcliffe cabin. Eva and I had become casual friends the year before, and we knew that we were compatible, but when we immediately settled into living easily together like very old friends—‘my Rosie and your Jean,’ said Eva—it made life and work extraordinary. The art of female friendship, poetry and prose as any friendship, is a substantial joy for women who have experienced it. It creates a respectful space for deep, mutual understanding and the insightful, sympathetic exchanges of stories and experiences. Sharing a work and living space and the art of friendship was a topic first brought up by Eva over a bowl of muesli sitting at the kitchen table: ‘Too bad we like those handsome men [she had two specific men in mind], or we could just live together for life.’ That was true, I said, that was very true. In every sense we were in a perfect place for each of us to work.

Eva Hesse, No title, 1969. Private collection © The Estate of Eva Hesse

Eva Hesse, No title (For Gioia), 1969. Private collection © The Estate of Eva Hesse

‘Quartet’ was a simple cabin that had had artists living in it for six months of the year for sixty-four years, starting with the original members of Byrdcliffe, a utopian Arts and Crafts community for which it was built. It had four small rooms strung out in a row like rectangular beads, with one exterior door facing a dirt clearing that ran the length of the building (‘terrace’ would be too grand a word) and another exterior door opening onto the steep incline of Mount Guardian, a small mountain of the Eastern Catskills that towered behind us. We were living in the middle of a large, typically northeastern hickory and oak wood, which climbed and covered more than a thousand acres behind the cabin. Eva heard for the first time wood thrushes sing their hauntingly distinct songs each evening.

The cabin—sitting on a dry stone wall foundation, of simple wood construction, and with eight-over-eight windows filled with wavy turn-of-the-century glass—was a ‘real’ place, one showing the natural beauty that requires a fundamental life, with few material things, and no wasting of time. True to the precepts of the utopian community’s founders, by 1969 the cabin was a comfortable part of the natural place, holes where wood knots had fallen out of the wallboards allowed glimpses of the trees, and the wooden floor was falling gracefully back into the earth itself. We were not surprised that we did things around the house the same way, much of it old-fashioned and steady: make our beds quickly each morning, sweep the floors each evening, and when something was wrong, which of course there has to be, ‘too much salt in this soup,’ ‘not enough,’ ‘did we burn it on the bottom?’ It was always said kindly and we were happy that we always agreed on the issue at hand, and the one who made the soup had no hurt feelings, overt or hidden.

Although we were both sensitive to feelings, when it came to simple things we both loved good soup and the lesson the mistake had taught us was welcomed. Blame could be an unkind and pernicious power issue leading to never ending arguments which were not worthy of friendship. This was a conversation we actually had over a good lunch we had both prepared. Since we were also both extremely polite and careful as we talked about our lives and feelings, we experienced that lovely thing—safe in our new nest. ‘No enemy here,’ I said joyously. What chore needed to be done, I did on the spot without making a big deal of it. Eva liked that. (Later, at her own home and studio, I saw that she was usually a fastidious housekeeper.)

For the time being, we had no desire to spend hours cleaning. There would be neither excellence nor high standards in keeping house, although I did put up on the old refrigerator a few glossy magazine pictures of ‘old great house interiors’ to admit to their existence somewhere else in the world. The freedom of caring for the mundane without ever loosing ourselves in the threads of doing it made our lives unexpectedly happy. We didn’t have the longtime tests of roommates, yet we did have the love of friendship and old ‘family’ feelings that made our life together protected and close, agreeable to the only thing we wanted to do—make art while being as ‘awake’ in our lives as possible.

‘...we pledged ourselves to making art from the center of our world and committed life, a center that we both had touched, had experienced.’

For our lives we would live simply and do nothing that would enervate or distract us from our work, and by ‘our’ work we meant art, in all its complexities. ‘Excellence in art is all I care about,’ she said more than once, meaning the excellence gotten after study and knowledge and practice with no preconceived dogma or formula. The operation for a brain tumor that she was told was benign had been successful, and in this ‘right after’ period she felt alive and happy after having ‘narrowly escaped’; she felt she was being given incredible, beautiful time to continue making her art. Art made from the center of her dramatic life, art worthy of the mysterious inner place that held both object (event) and meaning that could bring you to a new way of being present. So we pledged ourselves to making art from the center of our world and committed life, a center that we both had touched, had experienced. Eva knew exactly what she was going to do: a series of paintings, paintings on paper. The cabin was a soulful place, and Eva loved it immediately. You entered it from a screened in porch, that allowed no insects in but enough natural light for drawing or painting.

Then, as in a railroad flat, one room brought you directly into the next: a sitting room, a kitchen, a bedroom, a small empty room that although dark had been used as a studio, and then the bathroom, with its necklace of high small windows. I made the first room off the porch into a kind of primitive sitting room with two comfortable daybeds that were on either side of the Franklin stove that luckily I had bought in the first cold month of spring. I offered Eva any room or rooms she wanted, but because of the light she decided we should work on the screened-in porch, and because it had started to rain and was cold, we decided to sleep in the sitting room with the wood stove. We carried a second table out to the eight-by-fourteen-foot porch and set it up next to the table already there. We made a trip to the good art store in town and, although money was not plentiful, Eva bought many sheets of ‘only the best watercolor paper.’ After I readied my palette (tubes of caseins, watercolors, and bottles of medium), Eva only used the color tubes, never the plastic medium. My table looked ordinary; Eva’s looked like an inventive painter/sculptor’s setup with many unusual tools and objects. She took one of my glass palettes; she was ready.

Materials used by Hesse during the summer of 1969 in Woodstock, New York. Photo: Jill Sterrett

It was Eva who established our daily work schedule. Your basic eight to five. At about five we stop and treat ourselves to other joys, dinner in town in the company of friends, she said. Add music to that I said. After all, we are in Woodstock. Although I had never painted like that, it sounded good to me. With the work schedule and the two tables, it felt as if we were two women workers at our benches. We awoke naturally at seven to the now-constant heavy downpour. Each morning and evening I kept the fire going in the stove, which kept the sleeping room warm. After feeding my two cats and having a simple breakfast of muesli or granola and tea, we worked all morning, never talking or stopping until noon, and then after a small bowl of soup or sandwich, we went back to work all afternoon. She was earnest about time and determined to get a great deal done each day.

Once or twice in the afternoon we went shopping in local hardware stores. Eva looked for cord, and found a handful of rubber worms used by fishermen. It was the immediate surprise and sensual feel of them that interested her. She bought a couple of fists full, food for the hand’s imagination. She said she might use them or an idea from them in a sculpture later, but she would play with them for a while, and I could already see by just picking them up that they had already called her to something. They went into her drawing box. Next to my table there was just enough room for a small easy chair in the corner, where in the afternoon I sat to write poetry or plan the programs for my educational television series on stories that I was preparing for September, but otherwise we both stood up at the tables, painting.

The only concession we made to the daily rain was to put on sweaters and jackets, and after a week we moved the tables back a little to the center of the porch. Twice we went down to the hot City for the day. Once, Eva had a meeting with Ellen Johnson of Oberlin and I did research on some stories for my programs and the second time I think Eva met with a museum curator but we came back to the cabin quickly to continue painting. A few times Peter Whitehead, son of Byrdcliffe’s founders, who ran Byrdcliffe in the most humanly way possible, stopped by in the late afternoon, once to bring us a Chinese teapot, and on the twentieth of July to invite us to supper and to watch the first moon landing on television, which we did. I invited him to tea, and Eva joined us in a wildly funny conversation about living in Byrdcliffe.

It was just the sort of thing that happened often—small and deeply satisfying times talking and sharing stories with artist friends at the Colony. Jean Russo stopped by on her way to Montreal on a vacation with her boyfriend to leave me her three cats. Eva loved the feisty, wild, new stray and thought about taking him home with her when the time came to go back to her two floor loft in the City. More life, ‘but maybe that’s too much,’ she concluded. By this time it had rained for weeks. One morning we woke up hearing a thundering sound. It was a newly formed stream running straight down from the mountain and raging right outside the cabin. I had to move the car quickly so it would not be swept away. ‘Just like our lives,’ said Eva, ‘right over the top.’

Eva Hesse, No title, 1969 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

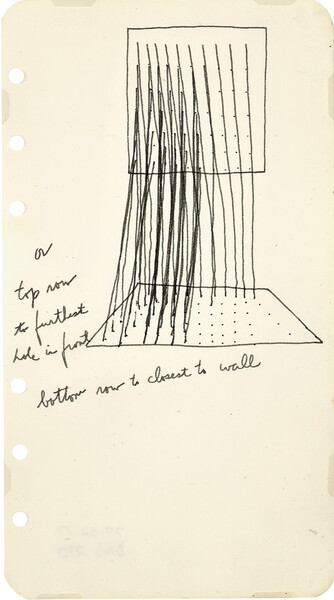

Eva Hesse, Study for ‘Contingent’, 1969 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

Every evening at about five we stopped work, had a cold drink or a hot tea and decided where we would go for the evening. We’d dress up a little and go out for dinner to the Elephant or the Espresso (as later in the City we went to Max’s Kansas City and St. Adrian’s), get the day’s news, talk to friends, listen to music, and never come home too late because of our early schedule. Ah! This is a good life right now: easy, good company, painting now, and making sculptures when the time comes. The schedule was only one example of Eva’s commitment to her work; she had no hesitancy, never drew back. She had had many successful shows, and critics had recognized her art, now she had to make pieces for museum shows coming up in the fall and spring. She never became sidetracked or diverted from her work. Thunder and lightning, hurricanes passed, and we worked on with our schedules intact. ‘Art history;’ she said, ‘I don’t want to waste time.’

She had a great sense of humor about everything, including growing irony about her own life. Although she talked about making sculpture in the fall in her New York studio, now she gave herself to painting on that wild porch. Eva’s table was a mass of jars, inks, and tubes of colors, but more amazing was the cache of objects with which she worked, the point ends of brushes for making invisible drawing marks after putting down a beautiful wash of color, crayon stubs and lead pencils to draw or break the surface of wet paint. She had an intimate knowledge of that drawing box, and instinctively picked up brushes, wax crayons, pencil stubs, brushes filled with water and color. She knew the condition of a pencil stub and what was left for her to use. She worked quickly and deliberately, sometimes turning the sheets of paper. Eva had very lovely, expressive hands, and her ‘hand’ was literally and metaphorically in all her sculptures; now I saw it in the paintings as well.

‘Art, like nature, had a prodigious complexity recognizable by those who could see it.’

After working for hours on a painting, she would begin another, and then take another sheet and begin work on it. There were painted sheets on the floor all around her. She studied them there, and then would pick up a few that were in different states of being finished and would put them up on walls inside of the cabin, over my bed so she could study them from hers, which she did for the rest of the day and into the evening, taking them down in the morning to work on them again until she was satisfied. If you had seen Eva painting then, you would know that it was still a very important part of her art, although I don’t think she would have spent so much time painting if she had been able to make sculpture that summer. (There had been a rumor afloat that year that figure painting, landscape painting, indeed maybe all painting was dead.) But she was where she was: in a cabin with her drawing box and a tremendous desire to paint.

It was a perfect time for this incredible series. She began the early works with vibrant color, those great oranges and pinks and the silver edges to the lopsided ‘window’ forms. The work was always abstract, there was no question of body or figure representations. None at all. They were images, complex and subtle, to be solved, arrived at, completed. She reached through everything she knew, had studied, had already accomplished, to work on these. Although these paintings began as highly colored, red pink orange—expressionistic—that was not what she wanted. She said it was ‘too easy, too pretty, too much of the past,’ so she worked layer over layer or, more complicatedly, worked unusual image next to another. The work was abstract, formal, cool, showing great deliberation, clear-headed and passionate at the same time. She never excluded the human emotional element, never abandoned the subtle form. If there seemed to be rules, then they were there to be broken. Everything was immediate and present.

The washes were all important, the paint thicknesses and the thin washes were worked in order to arrive at an abstraction that made sense. She was sure of what she was seeing, as if she were always ‘checking’ with some internal eye as well as with her eyes. So, what started in one way was not worked over or changed; rather, another consciousness was added over it. Things played off one another, and a brilliant image was achieved from varied and independently dependent parts. Art, like nature, had a prodigious complexity recognizable by those who could see it. All this done with an intense passion. I don’t use the word ‘passion’ lightly. By it I mean a serious Eros, child of Beauty and the ineffable place of creation, which does not use opposites, not two, but the possibility of a third image or fourth which brought Eva, with movement, to another way of seeing the piece—which in turn creates something brand new.

Eva Hesse, No title, 1969 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

Eva Hesse, No title, 1969 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

Eva had a movement that was deliberate and improvisational, expressing discipline and freedom. The unconscious was fair ground since good work can come from it, and if this spontaneous unconscious of her whole life met what she had really studied—the color, form, technique, and the art history (to which she knew she was making a contribution)—then the work would embody these forces in the mysterious combination that is recognizable in all great art where there is a close study of life itself, a subtle work which is conscious where it needs to be conscious and unconscious where it needs to be unconscious, in which there’s a fair chance to have one’s spirit, one’s genius fully expressed. It is the kind of transformed passion that creates paradox out of chaos, wholeness out of fragments, powerful art out of the common and absurd in human life. Eva had a great sense of humor and pain about the absurd in human life. Eva and I talked about making art and psychology, not only in relation to personal experience (although we told each other lots of stories that summer), but as two of the major disciplines we used to find substantial meaning in life.

We questioned and considered. Art and psychology were ways of questioning and learning that had given each of us a subtle education. Psychology gave us a way to understand the human psyche, while art pointed us to the nameless place. When telling our stories, we found that we had both pledged ourselves to this art path since childhood. Psychology came later. Eva was psychologically astute, profoundly intelligent, an original thinker. We had both experienced events that tainted our present lives but at this time we were committed not to a dead past but to being fully conscious in the present. Eva had experienced great fear as a small child, and in the April just past, at age thirty-three, the possibility of her own death from a brain tumor. Honest actions appropriate to the present that are not governed by the past—express these and you have a valuable, hard-won freedom. With desire, genius, and this freedom, she made new art. Eva felt she had nothing to lose.

Others might walk away from the shadow, but Eva went further in to bring back, with consciousness, what she found there. I saw her make some good ‘food’ from it. I read aloud from the diaries of Delacroix, the letters of van Gogh and Keats, the poems of Dickinson, and W.S. Merwin’s translation of Antonio Porchia, who wrote ‘I know what I have given you, but I don’t know what you have received.’ We were committed to being exactly where we were, no false masks and no stance. ‘We are not exaggerators or liars,’ said Eva more than once. She was committed to the truth, both the literal and the metaphoric, that which could be described in physical terms, and to the subtle and varied meaning that lay in the layers. Once when I was describing something we had seen, our visitor said, ‘Oh! That couldn’t have happened,’ and where someone else would have laughed and let it pass, Eva stopped, and said, ‘Gioia never exaggerates.’

I was startled that she knew this, since poets and storytellers are often accused of ‘exaggeration’ and the heat that passes by more undemonstrative souls called ‘drama,’ but she understood the difference, for she too never lied, never exaggerated. It was her pledge to this trait that gave her the freedom to express deeper layers of ‘what she saw and understood.’ Eva was not afraid of her intellect or her emotions. This is what allowed her to paint images that were on the one hand visually beautiful and evocative, and on the other startling and absurd, images that speak to her specific life and to our essential lives. In the last paintings, made in Byrdcliffe and later back her studio, Eva produced powerful art that embraced paradox. She painted and worked with ardor on those paper paintings and achieved paintings and drawings as wisely enduring and deeply eloquent as a Taoist text.

Materials used by Hesse during the summer of 1969 in Woodstock, New York. Photo: Jill Sterrett

The summer was over and Eva and I were ready to go back to our work and lives in the City. I drove Eva to her studio where she picked up working on pieces where she had left off while having lots of ideas for new sculptures. I went back to my work at the Educational TV Station and back to my study where I continued to write poems. My artist friend, (one of the handsome men Eva had mentioned) who knew Eva, came back from his family home in North Carolina to his apartment and studio with a series of drawings for an Anonima Group show. We continued working all day and going out for other joys, talks and dinners. When Eva had headaches again, she underwent a series of tests. She came to stay with me during chemotherapy. After this, she went back to her studio and continued to make one amazing piece after another.

Eva Hesse’s art was shown, written about, and critically admired. Her devoted family, Helen and Murray and Murray’s friend David and I, along with other loving friends, helped to care for Eva while she continued to be Present with that Eva depth of soul and spirit: actively loving her family and friends, creating great sculptures—living a full life. She wrote in her diary. People write in diaries for many reasons. Eva wrote when she needed to find clarity in the painful truth of her life, when she wanted to describe what she was feeling and thinking, when she wanted to tell herself to be courageous, when she wanted to write about art and the making of art. There is an urgency in rain; I have always written in my notebooks on two occasions especially: when it rains, and when I am traveling. One is a naturally introverted time for me, the other is a liminal one, uncertain, new, adventurous, and possibly transforming.

Diaries are often used to record extraordinary states of mind, which, having been described, naturally pass on until the next time. Eva wrote on pads, in books, in diaries when she was feeling the need to record her deepest, most honest feelings. And since she was pledged to telling the truth, what else would she do but write how she was feeling at the moment? But to understand the strong, funny, confident, brilliant, life-loving Eva that I experienced that last year, you would have to see the diaries as only part of her being. She faced dying with courage and equanimity. She was totally alive creating her sculptures. Once, when I came into her hospital room she was sitting up and looking at a pad on which she had drawn three enormous legs and feet, a model for a sculpture piece, she called it. She was smiling as she turned the pad, and when I looked we both burst out laughing. ‘I know,’ she said, ‘they really are funny.’

Eva knew that as a child her life played out in great events, more dramatic than most children’s, and she accepted this as true, and she did not shy from its words and expressions. I think first of the diaries that Eva’s father wrote for his daughters. She was a Jewish child born Hamburg in 1936. In 1938 she traveled to the Netherlands on a children’s transport with her sister Helen. They did not know if they would ever see their parents again. Eva searched the impossible to explain the truth of what she knew of the terrific, terrible tragedy of human life, of what she often called the absurd. What else would interest her? Most people I guess would hide this fear or pain, but she would not. How could she ever truly live her life if she lied? If she were to admit fully where she was, she would put nothing between herself and her life; understanding this allowed her to put nothing between that center and her art. She would investigate her life, probe it, look at it, call it names, express it, make a profound art out of what is essentially an ephemeral life with hints and/or experiences of ‘the other,’ transcendent and deeply moving.

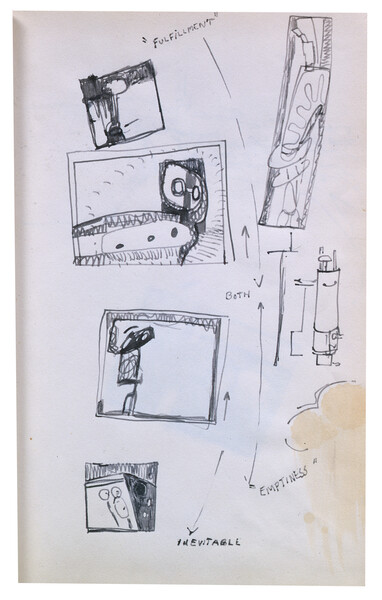

A drawing in Hesse’s sketchbook from 1961. Private collection

Eva Hesse, No title, 1968 © The Estate of Eva Hesse

One afternoon after I had read her some new poems, she stopped painting for a minute, looked up, and said, ‘I wish I could be a writer. You only have a pen and a pad. You don’t need to deal with all this stuff.’ ‘Oh! Go on,’ I said, ‘Look at what you’re doing with a little stuff and a drawing box,’ and she laughed, agreeing. An important part of Eva did write, about art and what in her life brought her to it. When she was writing about her life, she was writing about her desire to have the freedom and the power she wanted, and it was attaining that which made her genius possible.

Eva was an original talker and thinker. If you read only anguish in the journals, then you mistake a part for the whole, the fleeting for the enduring, and forget that she was always engaged in the practice of being brutally honest, for personal anguish was only meaningful if you could feel and see it to be a journey through the mess and beauty that is human life, and that, with honesty and courage, can lead you to make true art—an art that human culture needs to describe and see itself. When I read the journals, I see them as her way to describe that metaphysical journey. Eva Hesse loved to make diagrams of these metaphysical states which have to do with her art, with all art. In one notebook from 1961 , she made drawings in two columns, and in between them she made a diagram in which she wrote FULFILLMENT at the top and EMPTINESS at the bottom. In between, she drew arrows going both ways and wrote BOTH. And to the side is the wonderful word INEVITABLE.

‘Forms Larger and Bolder: EVA HESSE DRAWINGS from the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College,’ opening 5 September at Hauser & Wirth New York, 69th Street, illuminates the important role that drawing played in Hesse’s career. ‘Forms Larger and Bolder’ is accompanied by ‘Eva Hesse: Oberlin Drawings,’ a new 428-page publication by Hauser & Wirth Publishers that illustrates the Allen Memorial Art Museum’s extensive collection of Hesse works on paper.