Portfolio

Max Bill and the Dessau Bauhaus: A design pioneer’s origins in painting

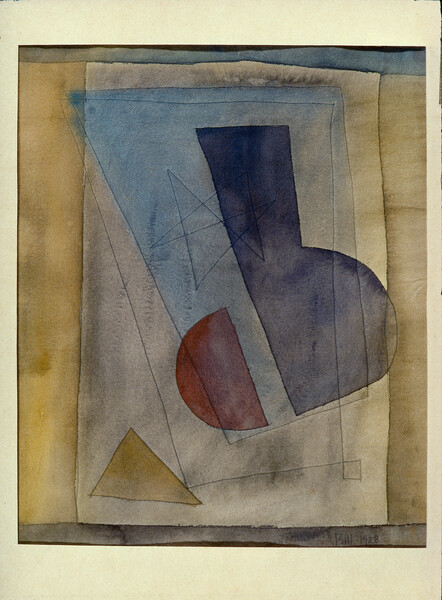

Düstere Bewegungen (stilleben) (Gloomy Movements [still life]), 1928, gouache over watercolor on paper © Angela Thomas Schmid, © 2019, ProLitteris, Zurich. All artworks: Courtesy Max Bill Georges Vantongerloo Foundation

‘I have caught the painting disease.’—Max Bill to his teacher László Moholy-Nagy, Dessau Bauhaus, 1927

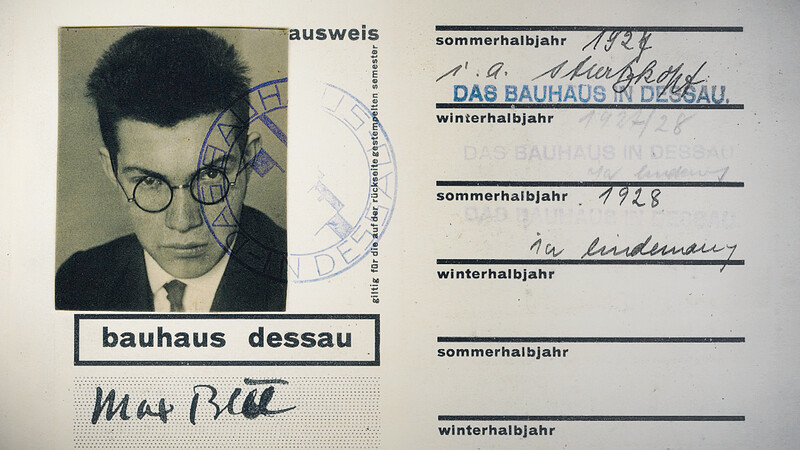

On the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Bauhaus, Ursula follows Max Bill—one of the most influential designers of the 20th century and a personification of the Bauhausian dream of erasing the boundaries between fine and applied arts—back to his student days (1927–29) and his still little-known work as a fledgling painter, in thrall to his teachers Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Josef Albers. Bill, who in his teens had studied silversmithing in Zurich but was expelled from the School of Applied Arts for being too forthright with his opinions, was accepted for the summer 1927 semester at the Bauhaus in Dessau, founded there only two years earlier after political pressures forced the closing of its original Weimar home.

Max Bill's student card from Bauhaus Dessau.

Ohne Titel, Entwurf für eine Wandmalerei mit grossem ‘O’ (Untitled, draft for a wall-painting with a large ‘O’), 1932, gouache.

‘I can still remember that very morning, just before I arrived at the railway station in Dessau, the facade of the Bauhaus building suddenly appearing opposite,’ Bill (1908–94) said years later. ‘There was nothing else like it: striking white walls and large dark glass facades and, in the foreground, the students’ house with balconies and red lead doors. Sensational!’

Rauchbläser (Smoke Blower), 1929, painting on hardboard.

Teilung und Multiplikation (Division and Multiplication), 1929, gouache over watercolor on Japanese paper.

He began studying metalwork under Moholy-Nagy but quickly stopped attending those classes as painting took up more and more of his time; the influence of Klee, in part because the two could speak together in Swiss-German, was powerful. From Albers, he began to learn a philosophy in painting that would lead him to articulate his own language in design, things ‘less to do with painting than with the collective relationship that design-oriented people have with their environment. It was the stimuli radiating from Albers that activated the will in me to find the fundamentality of a thing.’

Hermaphrodith (Hermaphrodite), 1929, ink on Japanese paper.

Tiefer Gesang (Low Chant), 1928, gouache over watercolor on paper on original cardboard.

Bill’s colorful, unfettered student expressionism stands in stark contrast today to his legacy as a poetically rectilinear designer, the paradigm of Swiss harmony and functional economy. But his training with canvas and brush never left him. ‘Painting was a completely natural thing for me to do,’ he said in 1993, for an essay by the art historian Dr. Angela Thomas Schmid, his widow, who directs the Max Bill Georges Vantongerloo Stiftung in Zurich. ‘And this naturalness has remained with me, even to this day.’

Siamesische Zwillings-Akrobaten (Siamese Twins Acrobats), 1929, oil on cardboard.

No. 44, 1929, Indian ink on Japanese paper.

Konstruktion (Construction), 1934, oil on compressed wood.

To coincide with the centenary of the Bauhaus’s founding, Hauser & Wirth Zurich is presenting a major exhibition, ‘max bill. bauhaus constellations,’ on view through September 14, 2019, curated by Dr. Angela Thomas Schmid, president of the Max Bill Georges Vantongerloo Stiftung.