Conversations

A conversation between Jerry Gorovoy and Diana Widmaier Picasso

(Left) Ervin Marton, Picasso at Golfe-Juan, 1948 © Ervin Marton Estate Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Michèle Bellot. (Right) Berenice Abbott, Louise Bourgeois, 1949 © The Easton Foundation. Photo: Berenice Abbott

Jerry Gorovoy, former studio assistant to Louise Bourgeois and now head of her foundation, The Easton Foundation, sits down with Diana Widmaier Picasso, art historian and granddaughter of the late great master, Pablo Picasso. This conversation anticipates ‘Louise Bourgeois & Pablo Picasso: Anatomies of Desire’ curated by Marie Laure Bernadac at Hauser & Wirth Zürich, which brings together over 90 works including paintings, sculptures, and works on paper from important public institutions and private collections.

Jerry Gorovoy: In my introduction to Marie-Laure Bernadac’s exhibition catalogue, I suggest that both Louise Bourgeois and Pablo Picasso fell sick from love. Freud tells us that falling in love is on one level a defense against falling ill, and, in turn, that the inability to fall in love leads to illness. I associate Picasso with the former and Bourgeois with the latter. Would you agree with my way of framing this key difference between the two artists?

Diana Widmaier Picasso: For the Surrealists, love was the supreme ‘where the spirit and flesh cease contradicting one another’ and they held that all passion leading to sexual exultation was a positive good, not to be denied by taboos. It could have been that through André Breton and Paul Éluard that Picasso found an intellectual basis for resolving the sexual conflict that invaded his life and work from the 1920s. His choice to create a mythological creature, the Minotaur, which carries loves and fights, is a good example to illustrate your theory. As Kahnweiler wrote, it, ‘…is Picasso himself. It is a symbol of his naked soul.’

JG: What function do you think romantic love played in the gestation and making of a work of art by Picasso?

DWP: Romantic love shines out as a crucial catalyst in his development as an artist. Each one of his muses stands for a different period in his career, representing a complementary or opposing ideal that inspired the evolution of a new visual language—just as they became involved with him, so he was dependent on them. Women were all important in his life because he was always apt to associate sex with art—the procreative act with the creative act.

‘She wants to walk around and enter her installations; she wants to smell, touch, and feel, and to evoke all five senses.’

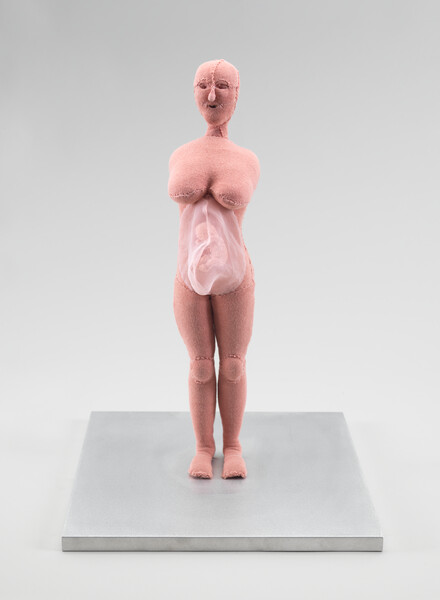

JG: Your essay on maternity turns upon one of the key biological differences between men and women. For Picasso, the swollen belly and enlarged breasts of the pregnant woman are objects of contemplation and desire. Formally speaking, I tend to consider most of his sculptures as images and objects rather than experiences. They seem to me to be more pictorial, that is, an extension of his painting in three-dimensional terms, and, as such, have more to do with the eye rather than with the body. Do you agree with this assessment?

DWP: Picasso tended to glorify maternity. His sculptures have a symbolic significance and are often represented in a stylized way and dedicated to female fertility, akin to fertility idols.

JG: By contrast, Bourgeois’s sculptures are reactions to her bodily states. Her physical sensations are paramount to the development of a form: the experience of carrying a child within her body, giving birth, and breastfeeding; the feeling of being inside or, conversely, of having something inside; the alternation between states of fullness and emptiness; and so forth. Perhaps this is because her sculptures are more experiential than his. She wants to walk around and enter her installations; she wants to smell, touch, and feel, and to evoke all five senses. Why do you think Picasso dealt with sculptural space in the way that he did? How does his handling of space compare with that of Bourgeois?

DWP: Because Picasso can only see pregnancy as a spectator! It is different for Louise Bourgeois. The radical transformation of society in the 1960s and 1970s began to change how we see pregnancy. Pregnancy is now perceived as a special moment in a woman’s life. Although an artistic career and motherhood had long seemed irreconcilable, Bourgeois takes a fresh look at pregnant women by drawing on her own personal experience of pregnancy. Her works are not intended to realistically reflect this state, however. Bourgeois’s performances reflect a second, more symbolic birth as an artist.

Louise Bourgeois, Umbilical Cord, 2003 © The Easton Foundation / ProLitteris, Zurich. Photo: Christopher Burke

Pablo Picasso, La femme enceinte 1950 – 1959 © Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zurich. Raymond and Patsy Nasher Collection, Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas. Photo: David Heald

JG: In your essay, you quote Dora Maar as saying, ‘Once a girl has had a baby she becomes [Picasso’s] enemy.’ To be pregnant with his child would appear to be a confirmation of his virility and a consummation of his desire to live forever through his creations. Is being pregnant or being a mother incompatible with being a muse? Or is it that, per Karen Horney’s theory of womb envy, Picasso was envious of the superior creativity that a woman’s ability to give birth represented?

DWP: This reminds me above all of a conversation recalled by Françoise Gilot in 1948, which seems to me to define Picasso’s position on motherhood: ‘I know just what you need’ he told me. ‘The best prescription for a discontented female is to have a child.’ I told him I wasn’t impressed by his reasoning. ‘There’s more logic to it than you think,’ he said. ‘Having a child brings new problems and they take focus off the old ones.’ At first that remark sounded merely cynical, but as I thought about it, it began to make sense to me, although not at all for his reason. I had been an only child and I hadn’t liked it a bit; I wanted my son to have a brother or sister. And so, I didn’t raise any objections to Pablo’s panacea. As I began to think back on our life together, I realized that the only time I ever saw him in a sustained good mood—apart from the period between 1943 and 1946, before I went to live with him—was when I was carrying Claude. It was the only time he was cheerful, relaxed, and happy, with no problems. That had been very nice, I reflected, and I hoped it would work again, for both our sakes. I knew I couldn’t have ten children just to keep him that way, but I could try once more at least, and I did.’

JG: To me, the terrain that Picasso and Bourgeois share is the realm of sexuality, however differently it informs their work. Do you think that Picasso, for all his superhuman vitality, nonetheless expresses a fear of sex in his work? Is there an equation between sex and creativity in Picasso’s work, and if so, is the fear of sex connected to the fear of the loss of his creative powers? Is there a specific date or work where the fear of death seems to come to the fore?

DWP: I was fortunate to meet Leo Steinberg, the late art historian who did the first major analysis of the Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. He was impressed that even at an advanced age Picasso never lost his desire. I also think that desire is the most important thing and channels our sexual energy. There is definitely a fear of death behind Picasso’s explosion of sexuality. Eros holds back Thanatos. But I think his voracious creativity distracts him from the preoccupation of losing his young appetite. In fact, he feeds his libido with the stimulating late works including the numerous erotic works on paper and the extraordinary print series called 347, where he fantasies about Raphael and his tumultuous love affair with his muse La Fornarina, with Michelangelo and the Pope as witnesses to the scenes.

JG: Are there any stories that your mother told you that gave you an insight into Picasso’s art?

DWP: I was always fascinated by the materials that Bourgeois selected for her works. My mother always insisted on the quality and diversity of material that my grandfather used, or sometimes just preserved, in the hope it might serve a purpose. While I was looking through drawings and sketchbooks with her, she stressed how much respect Picasso had for beautiful paper or pencils, which were particularly difficult to access at certain times of his life (either because they had no money or it was during the war). I believe his love for the materials transpires in his work just like it does in the work of Louise Bourgeois. I find the way the paper, cardboard, and fabric are nailed together also very erotic. By mixing them, he is himself giving birth to a form.

Curated by Marie-Laure Bernadac and organized in close collaboration with the Louise Bourgeois Studio, ‘Louise Bourgeois & Pablo Picasso. Anatomies of Desire’ is on display at Hauser & Wirth Zürich, 9 June – 14 September.