Conversations

A conversation on Max Bill and Georges Vantongerloo

With Dr. Angela Thomas Schmid and James Koch

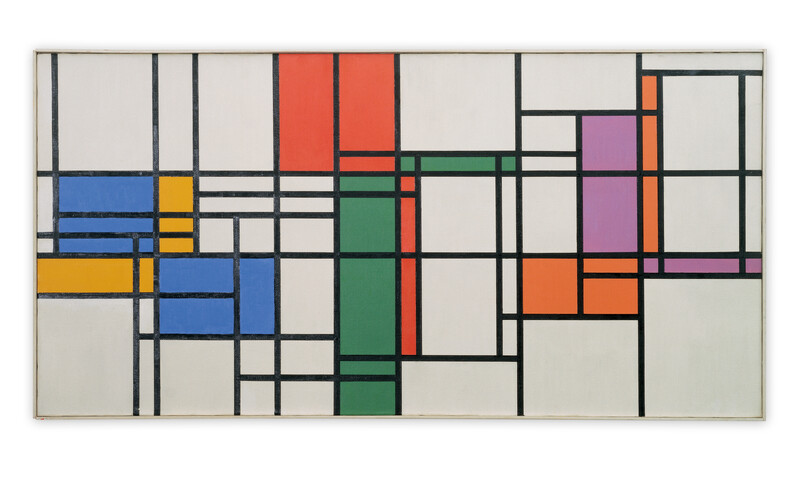

Max Bill, horizontal-vertikal-rhythmus (horizontal-vertical rhythm), 1943 © Angela Thomas Schmid/ProLitteris

James Koch is an Executive Director at Hauser & Wirth, and is responsible for the gallery’s activities in Switzerland including oversight of the public gallery spaces in Zurich and St. Moritz, and the semi-private chalet in Gstaad. Ahead of Art Basel 2019, he spoke with Dr. Angela Thomas Schmid on the Bauhaus exhibition she is curating in Zurich, and the work of Max Bill and Georges Vantongerloo.

James Koch: We are proud and delighted to present the exhibition you curated, ‘max bill. bauhaus constellations’ at Hauser & Wirth in Zurich. It shows the influence of the Bauhaus masters on the work of Max Bill. Which personalities, and specifically which artists, were decisive for him? What ‘lessons’ had an impact on his later oeuvre?

Dr. Angela Thomas Schmid: What particularly impressed Max Bill as a student at the Bauhaus in the foundation course taught by Josef Albers was the latter’s moral and ethical stance. Albers advised students that they should only ‘release’ their products into society if they were fully convinced of them. In later years, as director of the School of Design in Ulm, Bill tried to convey the same philosophy to his students: they should be able to justify their works, to ‘account for them’ in order to convince potential clients (e.g. in industry).

Bill, who had been searching for ‘clarity’ at the Bauhaus, learned everything he needed to know for his own architectural projects from the Dutch architect Mart Stam in the latter’s statics class.

On a personal level, and initially in terms of style as well, Bill had an affinity for the Bauhaus master Paul Klee and his work. The analytical drawings from Paul Klee’s pedagogical instruction at the Bauhaus had a lasting influence on Bill’s development as an artist. Visual attestations of this can be found in the exhibition ‘max bill. Bauhaus constellations’ at Hauser & Wirth in Zurich.

László Moholy-Nagy, another Bauhaus master whose metal workshop was only briefly attended by Bill, put so much trust in him that after the end of the second world war, he asked Bill to join him in the United States as a lecturer at his ‘new Bauhaus’ in Chicago. Bill declined the offer, preferring to stay in Europe at the time.

Dr. Angela Thomas Schmid and James Koch. Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

Georges Vantongerloo, (I) étude la haye, 1918 © Angela Thomas Schmid/ProLitteris

James: The friendship with Georges Vantongerloo is recognized as having been especially close and important for Bill. Is there a certain period in which this shared connection is visibly reflected in their oeuvres? How did the friendship otherwise manifest itself?

Angela: Soon after completing his studies at the Dessau Bauhaus, Bill discovered his own artistic path. In his later creative work, he was greatly influenced by the aesthetics of the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, whom he first visited in 1933 in his Paris studio, and the Belgian-Flemish painter and sculptor Georges Vantongerloo. Bill met the two artists, Mondrian and Vantongerloo, numerous times after joining the Association Abstraction Création—Art Non-Figuratif (Paris), along with other important artists of this international group.

Vantongerloo, an innovative pioneer of modernism, became Bill’s closest friend. After Vantongerloo’s death in 1965, Bill inherited most of his friend’s artistic estate as well as his archives, which are now held in haus Bill in Bumikon.

James: We are looking forward to presenting important works by Max Bill and Georges Vantongerloo at Art Basel. Can you explain more about these works and their meaning within the oeuvre of the two artists in general?

Max Bill and Georges Vantongerloo, 1965 © Angela Thomas Schmid/ProLitteris. Photo: Carmen Martinez

Georges Vantongerloo, Zittende Vrouw (Sitting Woman), 1916 © Angela Thomas Schmid/ProLitteris. Photo: Jon Etter

Angela: The two works by Vantongerloo are a figurative painting of a seated woman wearing red stockings, originally titled ‘zittende vrouw’ (1916), as well as the abstract depiction of a seated figure, ‘étude, la haye’ (1918). The work étude, created during Vantongerloo’s exile in the Hague in the Netherlands, is an important transitional work as a successful example of abstraction, an icon of art history.

Henceforth Vantongerloo would no longer engage in abstraction, but—as Bill put it—would only paint ‘concretely.’ Vantongerloo created this standard work when he was a contributor (medewerker) of the Dutch magazine ‘De Stijl’ published by Theo van Doesburg. Vantongerloo’s ‘réflexions’ texts were also published in ‘De Stijl’.

In June 1943, Mondrian sent a postcard to Bill from New York: ‘I’m working. Had another solo exhibition and sold a picture to the Museum of Modern Art.’ Impressed and inspired by the aesthetic of Mondrian, whose Paris studio was first visited by Bill (accompanied by Jean Arp) in 1933, Bill created his work ‘horizontal-vertical-rhythm’ in 1943; this can be seen at Art Basel 2019.

When Bill organized the exhibition ‘concrete art’ at Kunsthalle Basel in 1944, where Mondrian was represented with ten works from Swiss collections, he received the message that Mondrian had died in New York on 1 February 1944.

At the opening of the ‘concrete art’ exhibition in March 1944, the Basel museum director Dr. Georg Schmidt compared piet Mondrian's works to those of Max Bill. Georg Schmidt noted the following differences in content and substance: while Mondrian's art is defined by ‘the strictest scale of the ordered, formed, measured,’ the works of the 36-year-old Bill evince ‘acerbity and ingenuity.’

The above works by Georges Vantongerloo and Max Bill are part of Hauser & Wirth’s presentation at Art Basel, from 13 – 16 June 2019.

All rights reserved. Without permission through ProLitteris reproduction and any other use of the work besides the individual and private consultation are forbidden.