Essays

Arshile Gorky: The Liberation of an Artist

On the occasion of ‘Arshile Gorky, 1904–1948’ at Ca’ Pesaro International Gallery of Modern Art

by Saskia Spender

Arshile Gorky, Landscape-Table, 1945 © 2019 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Centre Pompidou, Museé d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle, Paris

A hundred years ago, the teenage Arshile Gorky got as close to Venice as he would ever be in person, when the boat taking him from Athens to Ellis Island stopped in Naples. Spiritually though, he was never far from the art of Pompeii, of Paolo Uccello and Giorgio de Chirico, and indeed he was happy to work ‘as fast as Tintoretto,’ because, as he once said, ‘when we are in tune with our times we do things with greater ease’[1] Not only did Gorky feel at one with his times, but also that through painting he drew from the eternal—where his chosen ‘ancestors,’ from Rimbaud to Picasso, also lived.

Four features in the story of my grandfather’s career stand out for me. The first is simply how much work he managed to pack into his mere twenty years of activity. Despite much of his oeuvre being destroyed by fires, just under two thousand works exist, mostly in important museums and collections around the world.[2] The second is the way he projected his personality as an artist so powerfully among his contemporaries that they carried his reputation both before his prime and beyond his death. The third, related in a way to the second, is his complex relationship with the critics of the day: if Gorky felt at one with his times, their reception lagged behind. And, lastly, how in choosing to eschew all categories in favor of his own agency, he gained a shadow of shifting identity issues—arguably one he sought to avoid.

Gorky seems not to have given much attention in his life for anything other than art, almost as if aware of his own limited time.

Arshile Gorky, The Limit, 1947 © 2019 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS)

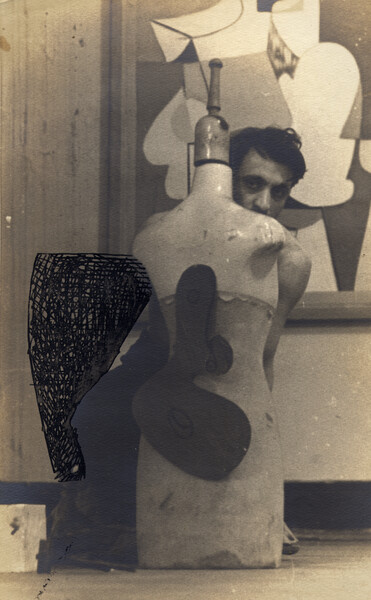

Gorky posing in his studio, ca. 1929 © 2019 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Long before reaching his own artistic maturity Arshile Gorky was recognized as a protagonist of the artists’ scene in downtown New York. The accounts of colleagues to whom he was close in the 1920s and 1930s, Stuart Davis first and then Willem de Kooning, describe a charismatic figure, a man from a resolutely unnamed country, with an invented name, an inaccessible past, and a highly individual way of expressing himself in speech and dress: ‘The atmosphere was so beautiful,’ de Kooning said of Gorky’s dazzling studio at 36 Union Square.[3] As soon as de Kooning ‘came to,’ taking in the bare walls, bleached floorboards, and storage side room, he said he was ‘bright enough to take the hint immediately’: art was central to this colleague’s life, coming before food and drink, let alone the swagger and the ‘jive talk’ for which he was notorious.[4] ‘He worked day and night, day and night.’[5]

Rake-thin and poor, Gorky invested only in first-rate materials and handmade paper: ‘ A massive easel of foreign make, great quantities of canvases of large size, hundreds of tubes of the most expensive colors, dozens of palettes covered with huge piles of paint, forests of fine brushes, bolts of linen for paint rags, and carboys of oil and turpentine. This is not an exaggeration…’[6] Gorky seems not to have given much attention in his life for anything other than art, almost as if aware of his own limited time (he had metastasized rectal cancer when he killed himself). While able to mix in different social circles, from the raucous evenings at Romany Marie’s to the private study of Alfred Barr in the Museum of Modern Art, Gorky’s important bonds tended to the singular. In a sense, his close friendship with John Graham made way for the one with Stuart Davis, who was dropped for Willem de Kooning, who was dropped for Roberto Matta, all dropped for a wife, and always all, including marriage, for painting.

In the feverish atmosphere of Depression-era New York, many artists felt drawn to organized movements: Gorky was happy to participate in the festive aspects of the Artists’ Union, making an extravagant float for a 1934 protest march. He left as soon as the discussion turned to suitable themes for revolutionary art. Nor did he agree with ‘geometrically’ prescriptive bodies, such as the American Abstract Artists. When his teaching jobs dried up he participated in the Federal Art Project, though not as fully as he did in his own work; Gorky painted his publicly commissioned ‘murals’ on canvas, and did not allow the designated mural assistants to help, presumably so that his work might one day be easily removed and exhibited differently.[7] The experience however was fraught with anxiety, first as questions were raised over his citizenship, then when his works were ill-received by the popular press, and finally when they were destroyed. Gorky’s profound rejection of politics emerged from his personal history: he had experienced the catastrophic consequences of political failure in his early life in Ottoman Anatolia.

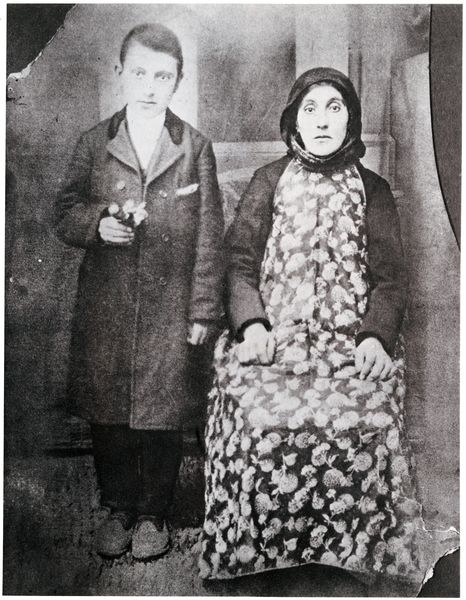

Furthermore, those members of his family who had been politically active had been failed by their ideals, or repeatedly failed him: none more deeply so than his father and elder half-brother. After leaving Lake Van in 1908, Gorky’s seniors settled in America with an assumption that they would send for the rest of the family in due course. They never did. In 1915 the situation in Van deteriorated to the point that Gorky’s mother had to flee with her small children to Yerevan. As a last appeal to her husband in America, she sent him a photograph of herself and their young son. There was no response, and she died of starvation in his arms. Some months later the city was besieged and fell. In the chaos that followed the two children made their way to Constantinople, subsisting in the port until they secured a passage with the help of an elder (matrilineal) sister in America. Once in Watertown, Massachusetts, where his father and brother worked in a factory and had bought a house, Gorky joined the Hood Rubber Company but was sacked for drawing on factory property: the male relatives were not impressed. One day Gorky found the photograph of himself and his mother in a drawer, picked it up, and walked out of their lives forever.

Arshile Gorky, The Artist and His Mother, ca. 1926–42 © 2019 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Alisa Mellon Bruce Fund 1979

A photo of Gorky with his mother taken in Van around 1910 and sent to Sedrak Adoian, Gorky’s father, in the United States

It is at this point that my grandfather changed his name. His first choice appears to have been ‘Archie Gunn,’ a Western-style character which, as a non-WASP, he discovered himself unable to inhabit beyond his sister’s front door. It is significant, however, that his choice delivered him not only from his patrilineage, but also from any particular ethnic identity, to place him instead generally ‘in the Caucasus’ and, more specifically, in the universal lineage of the arts. From there Arshile Gorky moved to New York City, and conducted his apprenticeship with groundbreaking artists of all epochs who resonated with him, from Fayum and Japan, to Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Joan Miró, mostly from reproductions and visits to museums. In other words, his education was visual, entirely self-directed, and focused on the material rather than theoretical aspects of painting.

While it is unclear whether he knew that Maxim Gorky was a pseudonym, any kinship to the celebrated poet did not withstand the scrutiny of Arshile’s own success. By the mid-1930s he was talking it down. By now he was firmly established in New York, showing work at the Whitney Museum Annuals and working on multiple versions of ‘The Artist and His Mother’, based on the photograph he recovered from his past. Yet there is no doubt that picking an illustrious alias wrong-footed Gorky’s early relations with the press, foreshadowing the later ambivalence from those art critics who sought a decisive break between European and American art. The artists’ agenda was different. De Kooning again: ‘You find a fellow who’s really good and you have a sense for it. It’s hard to explain,’ he said. ‘Gorky always had his own image. You know it’s like a flavor. The feeling, the way he painted the things, the way he drew. It was terrifically Gorky. His interpretation was always very Gorky. He understood everything. He had terrific, uncanny insight.’[8]

Gorky came to his fullness in the 1940s, a decade during which he was also having a family, and so, to a certain extent, removing himself from the metropolis. His greatest epiphanies began in the solitude of rural breaks in Connecticut and Virginia. This was also the decade when New York critics sought to define the art for an American century: Gorky’s former notoriety and relative isolation of the 1940s meant some were slow to recognize his developments. However, by the time of his death in 1948 he was regarded as a leading artist in the nascent Abstract Expressionist movement. A full ten years after he died, Gorky was included in Dorothy Miller’s traveling Museum of Modern Art show, ‘The New American Painting’, with six works represented—among which ‘Soft Night’, ‘The Limit’, and ‘Dark Green Painting’—introducing European audiences to a radically new experience of art. [...]

Arshile Gorky, Dark Green Painting, ca. 1948 © 2019 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art Gift (by exchange) of Mr. and Mrs. Rodolphe Meyer de Schauensee and R. Sturgis and Marion B. F. Ingersoll, 1995

Arshile Gorky, Nighttime, Enigma and Nostalgia, ca. 1931-1932 © 2019 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Whitney Museum of Modern Art. 50th Anniversary Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edwin A. Bergman

Although we cannot know how Gorky’s own work might have developed had he lived, his later works (like Terracotta or the black Pastoral) suggest he was finding a more essential line, sometimes scraped into the canvas, paring-down his compositions, and using fewer bolder colors including black. It was left to other painters, like Helen Frankenthaler and Cy Twombly, later Jack Whitten and Cecily Brown, to invoke his work in their own, just as the Italians Afro and Scialoja had. Thus, the artists made sure Gorky remained part of a living conversation, even if for a long time the critics settled on his place as a mere bridge between American abstraction and European Surrealism.

Today we wish to keep the bridges open, particularly in this city of many beautiful ones. In choosing to place himself outside given social and even art-historical categories, Gorky shows us the way to liberate ourselves from our temporal limitations. – The above is an excerpt from an essay included in the exhibition catalogue ‘Arshile Gorky, 1904–1948’, by Saskia Spender, the granddaughter of Arshile Gorky and president of The Arshile Gorky Foundation. Produced on the occasion of the exhibition, ‘Arshile Gorky, The Eye-Spring’ is a documentary film directed by Cosima Spender, granddaughter of the artist. The eponymous ‘eye-spring’ comes from the words of André Breton, who said of his friend ‘The eye spring ... Gorky is for me the first painter to whom this secret has been completely revealed’.

‘Arshile Gorky, 1904–1948’ is the first Italian museum survey on the career of a leading American painter. Presenting over eighty paintings and works on paper, the retrospective sheds light on the artist’s early artistic dialogue with Cézanne and his later influence on abstract expressionism. The exhibition is on view 9 May – 22 September 2019 at Ca’ Pesaro International Gallery of Modern Art, Venice.

[1] Matthew Spender, From a High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 151.[2] A number of paintings were destroyed in a relative’s house fire in 1934; Gorky suffered a studio fire in 1946; The Calendars was destroyed in a fire at the New York Governor’s mansion in Albany, NY, in 1961; and about fifteen drawings were destroyed in a plane crash in 1962.[3] Willem de Kooning, ‘Editor’s letters,’ Art News 46 (January 1949): 6.[4] Stuart Davis, ‘Arshile Gorky in the 1930s: A Personal Recollection by Stuart Davis,’ Magazine of Art 44 (February 1951): 56–58.[5]. De Kooning in Ararat: A Special Issue on Arshile Gorky, cited in Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, De Kooning: An American Master (New York: Knopf, 2004).[6]. Davis, ‘Arshile Gorky in the 1930s’, 56–58.[7]. Matthew Spender, ed., The Plow and The Song (Zurich: Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 2018), 113.[8]. Spender, The Plow and The Song, 49.