Essays

This is not a photograph

by Luc Sante

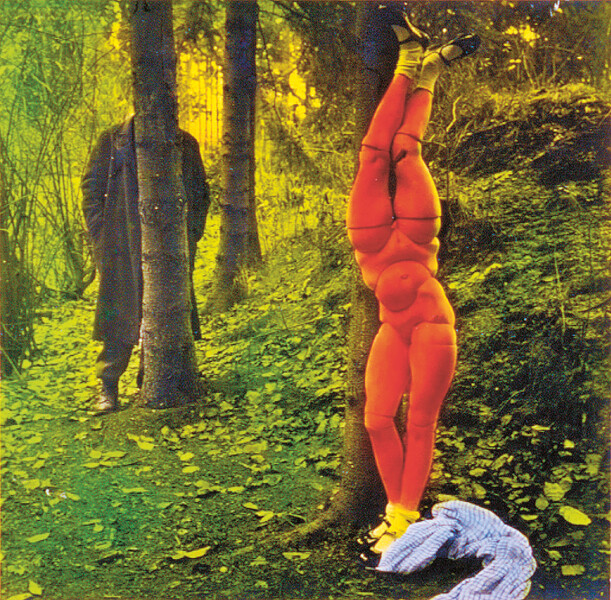

Paul Nougé, La naissance de l'objet from La subversion des images, 1929–30 © 2018, Artists Rights Society, New York/SABAM, Brussels. Courtesy Sylvio Perlstein Collection

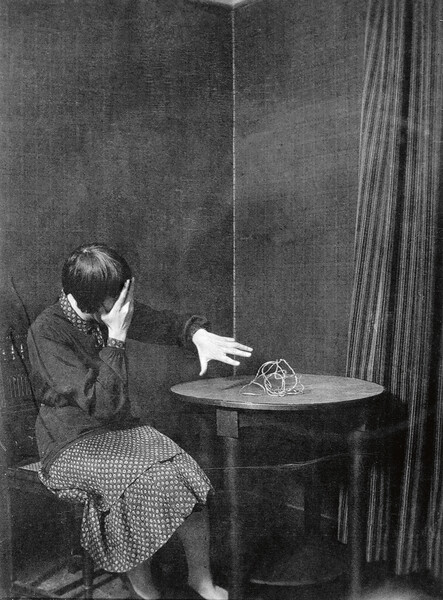

They are strange little pictures, the size of snapshots, and like snapshots, they include his wife and friends. But they depict an alternate world, with a tone that oscillates between humor and horror: a woman is frightened by a piece of string; two men seated at a table appear to clink glasses, but there are no glasses in their hands; a group of people stare intently at an empty corner of a room. A woman rests her head and arms on a table, with spheres of graduated sizes arrayed in an arc between her open palms. A pointing hand emerges from behind a door.

The pictures, exquisitely deadpan, are beautifully framed and lit, despite the fact that Nougé is not known to have made any other photos, before or after. They evoke spirit photographs, of the kind that rose to popularity in the afterworld-besotted late 19th century, showing mediums emitting spumes of ectoplasm or consorting with dubious sheet-draped revenants. Nougé’s pictures also suggest the paintings of René Magritte, which is hardly surprising since Magritte and his wife, Georgette, figure among the participants in these staged scenes.

What purpose, if any, Nougé intended for his pictures at the time remains a mystery. Three of them were published in 1954 and 1955 in ‘Les Lèvres nues,’ a post-surrealist journal edited by Marcel Mariën, but the set was published by Mariën only in 1968, a year after Nougé’s death. That little chapbook, issued in an edition of just 230, includes captions by Nougé that follow his usual artistic modus operandi, which was to pursue philosophical points aggressively, exhaustively and with no undue literary flourishes: e.g., ‘For the viewer, what consequence can follow from the spectacle of a woman terrorized by a piece of string?…It is a question of the abnormal relations that can arise between a human and an inanimate object.’

René Magritte, Portrait de Paul Nougé, 1927 © 2018, C. Herscovici, Artists Rights Society, New York. Photo: Bancque d’Images ADAGP/Art Resource, New York. Courtesy Musée Magritte, Brussels, Belgium

René Magritte, The Hunters’ Gathering, 1934. Standing, from left: E.L.T. Mesens, René Magritte, Louis Scutenaire, André Souris and Paul Nougé. Seated, from left: Irène Hamoir, Marthe Beauvoisin and Georgette Magritte. © 2018, C. Herscovici/Artists Rights Society, New York. Courtesy Latrobe Regional Gallery

Outside Belgium, Nougé (1895–1967) is remembered today mostly in the company of (and shadow of) his far more celebrated friend Magritte, who depicted him in a 1927 portrait as a bespectacled doppelgänger decked out in white tie. But getting reacquainted with Nougé’s slim, elusive oeuvre presents a rare opportunity to wander some of the more secluded passageways of surrealism, that juggernaut of European modernism, and also to revisit the ferment of early 20th century Brussels, which the critic John Russell once described as ‘the capital of the slow burn, the general headquarters of purposed absurdity and the last redoubt of a close-knit group of writers, painters and collectors who counted the rest of the world well lost.’

The Belgian surrealists set out to change life itself, but they were not about to tackle the problem by employing hot air from the unconscious. Rather, their main tactic was a kind of radical clarity.

Nougé was the leading theorist of the Brussels-based group of Belgian surrealists, a group whose very existence, properly speaking, was never quite resolved by the participants themselves. (The Brussels crowd had a counterpart in the southwestern province of Hainaut, somewhat differently oriented, led by Achille Chavée.) The Brussels surrealists—Nougé, Magritte, Camille Goemans, André Souris, Louis Scutenaire, E.L.T. Mesens, Paul Colinet, Marcel Lecomte, and later on Mariën, Christian Dotremont, Pol Bury and Marcel Broodthaers—sometimes cosigned tracts issued by their French counterparts, but sometimes they refused and sometimes they were not consulted; relations between the two bodies were often strained. Besides their disinclination to follow André Breton’s every whim, as their French colleagues were expected to, the Belgians maintained several significant theoretical divergences from the creed. They were suspicious of manifestos and loose prattle about revolution, for one thing (Nougé had been a founding member of the Belgian Communist Party in 1919, and was expelled from it in 1925). For another, as the poet and chronicler André Blavier wrote, ‘With the exception of Chavée and his circle, [the Belgian surrealists] proved themselves singularly skeptical with regard to automatic writing, oracular prophesying, the value of dreams and the exaltation of delirium, the delirium of dreams.’ In addition, they had little to no interest in alchemy or the occult, which had become major preoccupations of Breton’s after World War I.

The Belgian surrealists set out to change life itself, but they were not about to tackle the problem by employing hot air from the unconscious. Rather, their main tactic was a kind of radical clarity. Nougé, who for 30 years held a day job as a biochemist, believed that the task of poetry—a term he employed in its broadest sense—was to disturb mental habits, to break the template of conventional thought that kept people imprisoned in their lives. He believed that by pushing relentlessly on the pillars of cognitive convention, they would eventually give way. He was particularly attentive to the use of words, ever on the watch for contradictions, flabby reasoning and facile theorizing. In a concerted attack on Breton’s first ‘Manifesto of Surrealism’ in the journal ‘Correspondance’ in 1925, he turned Breton’s own words against him, quoting what the latter had written the previous year: ‘Words have a tendency to group themselves according to particular affinities, which generally have the effect of making them recreate the world along its habitual lines.’ So much for the liberating properties of automatic writing!

Raoul Ubac, Model for an Irrational Landscape, 1935 © 2018, Artists Rights Society, New York/ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy Sylvio Perlstein Collection

Marcel Broodthaers, Thighbone of a Belgian Man, 1964 © 2018, The Estate of Marcel Broodthaers/Artists Rights Society, New York/SABAM, Brussels. Courtesy Sylvio Perlstein Collection

Nougé—whose legacy lives on particularly in the work of Broodthaers, the subject of a Museum of Modern Art retrospective in 2016—wrote poetry of a disarmingly limpid sort, along with ample theoretical ruminations and exercises in what would later be termed ‘détournement,’ or ‘diversion,’ by his admirer and occasional pupil Guy Debord (who published his first three important theoretical works in ‘Les Lèvres nues‘ and modeled his own journal, ‘Internationale situationniste,‘ on its format). These efforts, which turned the oppressive use of language against itself through judicious correction, ranged from a systematic rewrite of a school grammar manual to a group of poems called ‘Transfigured Publicity,‘ in which bold typefaces of variable size were at least as important as the words themselves. (‘Transfigured Publicity‘ has just been published in an English translation for the first time by Brooklyn’s Ugly Duckling Presse.) In 1927 Nougé hired a cart to travel through the streets of Brussels carrying an enormous panel that read simply: ‘Look at this boulevard clogged with the dead: You are there.’ In the mid-1950s Mariën extended this pursuit by supplying ‘Les Lèvres nues’ with ferocious advertising parodies that look for all the world as if they had appeared in underground newspapers in the ’60s or punk fliers in the ’70s: ‘For a quicker death [an image of Socrates about to quaff the hemlock] drink Coca-Cola,’ or Straight to heaven [an airplane in flames plunging headlong earthward] with Sabena/Air France.’

Until an undisclosed private dispute ended their friendship in the early 1960s, Nougé and Magritte were inseparable, virtually one brain with two bodies. In part because Magritte engaged in the production of highly bankable goods—his paintings—he became world famous, while Nougé, who published little until Mariën began to exhume his manuscripts and publish them in the 1950s, seemed nearly to desire obscurity, albeit waveringly. (As he wrote to Breton in 1929, ‘I would like it if those among us whose names are getting to be known a bit would step aside.’) Nougé gave titles to many of Magritte’s paintings, and he seemed to infuse his friend with his philosophical rigor. Witness Magritte’s sole textual contribution to ‘La Révolution surréaliste,’ the essay ’Words and Images,’ which coolly enumerates various aspects of the relationship between the two without reference to dreams, the unconscious or any other surrealist hobbyhorse, insisting instead on a kind of analytical surrealism: ‘An object is never so wedded to its name that another cannot work just as well….Sometimes the name of an object can take the place of an image.…Everything tends to make one think that there is little rapport between an object and its representation.’

How can a photograph, a mechanical reproduction of what lies before the camera’s lens, be surreal? Shouldn’t surrealist photography be an oxymoron?

Man Ray, Meret Oppenheim at the Printing Wheel, 1933 © 2015, Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society, New York/ADAGP, Paris, 2018. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The same spirit lies behind La Subversion des images, which is a set of philosophical propositions and, as such, requires photographs cleansed of artistic or circumstantial distractions. Much like Magritte’s paintings of the same period, they are intended to be generic in everything but their central premise. For Nougé, they were simply a visual extension of his written work, and he failed to publish them at the time very likely for the same complex psychological and political reasons that caused him to keep the bulk of his manuscripts unread by others until the much younger and phenomenally energetic Mariën forced them into the open. It is doubtful he was aware—or would have been much interested to know—that he was contributing a major item to the pantheon of surrealist photography.

Which brings us to the question always running just beneath the surface of Nougé’s pictures and flowing out into the wider world of images made at that time and since: How can a photograph, a mechanical reproduction of what lies before the camera’s lens, be surreal? Shouldn’t surrealist photography be an oxymoron? As Rosalind Krauss wrote in the catalog for ‘L’Amour fou,’ the important survey of the genre that she and Jane Livingston mounted in 1985 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington: ‘It would seem that there cannot be surrealism and photography, but only surrealism or photography.’ She goes on to list the contradictions: Breton abhorred realism in all its manifestations, despised description of all sorts, believed strictly in visual art that arose straight from the unconscious through dreams or hypnosis or other altered states—and yet proclaimed as early as 1925 that books should be illustrated with photographs, had three of his own thus illustrated (‘Nadja’, 1928; ‘Communicating Vessels’, 1932; and ‘L’Amour fou’, 1937) and featured photography prominently in the journals he controlled, especially ‘La Révolution surréaliste’ (which reproduced four pictures by Eugène Atget, uncredited apparently because he did not wish his name associated with the movement) and Minotaure (which made capital use of surrealism’s brief collaboration with Brassaï).

Krauss cites Breton’s dictum in the prologue to ‘L’Amour fou: Photography & Surrealism’, ‘Convulsive beauty will be erotic-veiled, explosive-static, magic-circumstantial, or will not be at all.’ In ‘Minotaure’, where the prologue was first published, the three properties are illustrated by photographs: ‘erotic-veiled‘ by a Man Ray photo of an androgynous Meret Oppenheim leaning nude on the wheel of a printing press, her hand and forearm black with its ink; ‘explosive-static’ by a Man Ray photo of a flamenco dancer caught in full blurred sway, arms, hair and skirt all cresting; and ‘magic-circumstantial’ by a Brassaï photo of a potato caged by its tuberous outgrowths. She delineates the properties: Erotic-veiled ‘invokes the occurrence in nature of representation, as one animal imitates another or as inorganic matter shapes itself to look like statuary,’ while explosive-static relates to the interruption of movement and magic-circumstantial to the found object.

She further aligns these with the photographic strategies of, respectively, doubling (through double exposure or superimposition, for example), cutting (which might also be called ‘editing,’ in the cinematic sense) and framing. These join the array of special effects in the surrealist armory: solarization, negative printing, cameraless photography such as Man Ray’s rayographs, and also the specialties of the Belgian Raoul Ubac: ‘brûlage’, which involves melting the negative emulsion, and petrification, ‘a process of off-register sandwich-printing by which his images gained dimension, appearing as if they were in low relief.’ (In 2009, ‘The Subversion of Images: Surrealism, Photography, Film,’ opened at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the first extensive updating of Krauss and Livingston’s explorations in more than two decades.)

Hans Bellmer, The Doll, c. 1936 © 2018, Artists Rights Society, New York/ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy Sylvio Perlstein Collection

The prospect of surrealist photography is vast and unwieldy. Of the mass of art photos from the interwar years, the items that are definitely not surrealist probably constitute the smaller pile. It might seem as though all that is required for a photograph to fall into surrealist territory is to have an invisible question mark hovering over it. Man Ray is more responsible than anyone for this sweeping ambiguity. A charter member of the surrealist group, he had brought photography with him from New York; a Breton loyalist, he was immune to the leader’s frequent ukases and excommunications; a relentless experimentalist (and sometimes opportunist), he could slide his every change of direction into the surrealist canon. Despite Breton’s general distaste for commercial collaboration with bourgeois culture, this included Man Ray’s fashion photography. Hence the three beautifully framed and lit but otherwise rather conventional photos of women’s hats he published in ‘Minotaure’ in 1933, which do relate to the text they illustrate (Tristan Tzara’s ‘On a Certain Automatism of Taste’) but loom much larger—and have been many times reproduced independently—becoming erotic enigmas simply by virtue of context and authorship. There is little about them, however, that suggests they could not have been taken by fashion photographers of the time, like Baron Adolf de Meyer or Louise Dahl-Wolfe.

Man Ray, of course, gave surrealism many of its cardinal images in the form of photographs: ‘The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse’ (1924; a sewing machine wrapped in burlap and tied with ropes, first made in 1920), ‘Marquise Casati’ (1922; her eyes doubled vertically), ‘Le Violon d’Ingres’ (1924; violin F-holes painted on the odalisque back of Kiki de Montparnasse), as well as numerous rayographs and portraits, solarized and otherwise.

Claude Cahun, Heart of Spade, 1936 @ The Estate of Claude Cahun. Courtesy Sylvio Perlstein Collection

Man Ray, Untitled (Paul and Nusch Éluard), c. 1936 © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society, New York/ADAGP, Paris 2018. Courtesy Sylvio Perlstein Collection

But then there are the photographs commissioned by Breton for ‘Nadja’ and taken by Jacques-André Boiffard. If, as Breton wrote, ‘Swift is surrealist in cruelty; Sade is surrealist in sadism; Chateaubriand is surrealist in exoticism,’ these might be said to be surrealist in their anonymity. They are Parisian street scenes, illustrating, very literally, locations mentioned in the text, showing hotels, cafés, storefronts and monuments more artlessly than any postcard. Despite Breton’s later reservations (in his preface to the 1963 edition, he found the pictures notably less magical than the places they depicted), the photos are imbued with mystery by their very blankness—they look like newspaper photos showing the scene of the crime. Before the year of the book’s publication was out, Boiffard had broken with Breton, and he joined the dissident camp headed by Georges Bataille, supplying ominous and sordid photos of a big toe for Bataille’s essay on that digit.

If we were to judge the degree of surrealism in photographers’ works by their representation in Breton’s own collection, the clear winner would unsurprisingly be Man Ray, by whom Breton owned dozens and dozens of pictures, from masterpieces to snapshots.

But after that, things get a little more complicated. Breton owned 27 prints, for example, by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, of whom it might be said that he was surrealist only in reportage—his representations of Mexico do not strive for effects but artfully record the inherent surrealism of a country marked by the often dizzying juxtaposition of European and Mesoamerican cultures and the looming presence of death. Breton had 19 pictures by Ubac, who did not frequent any of the Belgian surrealist cabals but whose principal field of research was the nude female body and the violations that could be visited upon it in the darkroom.

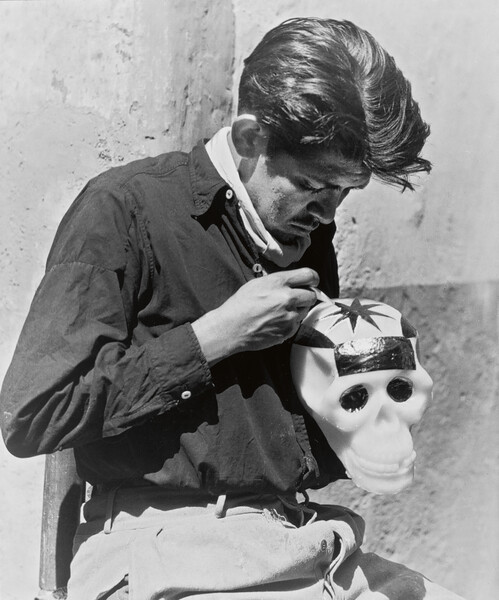

Manuel Álvarez Bravo, The Skull Factory, 1933 © Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, S.C. Courtesy Sylvio Perlstein Collection

He had 11 prints by Hans Bellmer, the German whose single-minded pursuit of violent eroticism through the medium of dolls’ bodies makes him one of the most durable illustrators of the surrealist concept; his frequent joining together of two pairs of legs at a common waist, for example, instantly establishes the idea of the ‘erotic-veiled.’ He had 11 pictures by Claude Cahun, all of them photographs of her tiny bell-jar assemblages, none of the work for which she is best known today: her shape-shifting self-portraits in a variety of costumes, dismantling gender roles. He had 11 photographs by Leo Dohmen, yet another Belgian, of a later vintage, who collaborated with Mariën on his long-banned erotico-anticlerical comedy ‘L’Imitation du cinéma’ (1960).

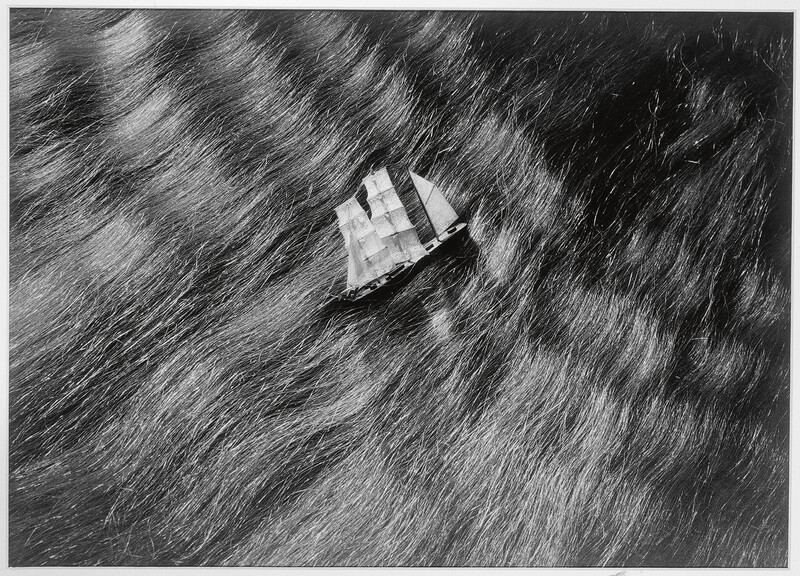

Breton also possessed photographs by Helen Levitt (three early pictures), by Brassaï, by Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose 1930s work is very close to surrealism though he never adhered to the group, and by E.L.T. Mesens and the Czech surrealists Jindrich Štyrský, Jindrich Heisler and Vítezslav Nezval. He had three pictures by Dora Maar, far better known for her turn as Picasso’s lover and model (1936–43, approximately) than for her own art, to no small degree because of her secretiveness and emotional turmoil, though she was as much a fountain of ideas as Man Ray. (Her advertising shot for Pétrole Hahn shampoo, which depicts a tiny sailing ship navigating an ocean of hair, is no less powerful and surrealist than her well-known, unsettling 1936 Père Ubu—made using what was possibly an armadillo fetus.)

We can add to this Breton pantheon other photographers who at the very least took coffee on Place Blanche with the surrealist high command: Maurice Tabard, a master of the double exposure; Roger Parry, with his gift for simulated crime scenes; Frederick Sommer, who found surrealism rampant in the high desert after moving from Brazil to America; Pierre Molinier, infamous for his fetishistic, sadomasochistic photocollages; Georges Hugnet, who, although not a photographer, pursued the possibilities of photomontage more assiduously than anyone else. And, finally, André Kertész, who took some of the most expressively surrealist photographs of the period (the de Chirico-like ‘Meudon’, 1928; the Parisian roofscape seen through shattered glass of‘ Broken Plate’, 1929; the clockface-shadowed ‘Pont des Arts’, 1929–32) while having no apparent connection to the group or its ideology.

Dora Maar, Untitled (advertisement for Pétrole Hahn), 1935 © 2018 Artists Rights Society, New York/ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy Sylvio Perlstein Collection

Paul Nougé, Femme effrayée par une ficelle from La subversion des images, 1929–30 © 2018 Artists Rights Society, New York/SABAM, Brussels. Courtesy Sylvio Perlstein Collection

Kertész could travel with brilliance and grace down virtually every avenue opened by photography in the first half of the 20th century. And with him in mind, in fact, it would not be difficult to mount a show of surrealist photographs taken exclusively by non-surrealists. For despite all of Breton’s attempts to define its meaning and patrol its borders, surrealism was and remains fluid and ungovernable, an entirely subjective optic, replete with contradictions. Surrealism results from chance procedures, unstudied juxtapositions, deracinated cultural artifacts, transient mysteries, erotic set dressing, unintended side effects. It grows wild in cities, especially in their most chaotically trafficked neighborhoods, especially when the spawn of clashing eras and unconnected cultures have been thrown together across the haphazard geometries of streets and walls. Any sufficiently open photographer’s eye will catch this transitory mating on the wing. Moreover, since surrealism, like humor, can simply result from thwarted expectations—I reach for my hat but instead grab a fish—all photography has to do to be surrealist, in the finally tally, is to be literal: A woman is frightened by a piece of string.

–

A version of this essay will also appear in ‘A Luta Continua: The Sylvio Perlstein Collection—Art and Photography From Dada to Now,’ to be published in conjunction with the exhibition of works from Perlstein’s collection that was shown at Hauser & Wirth in New York, 26 April – 27 July 2018.