Exhibition Learning Notes: ‘Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely. Myths & Machines’

Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely, Back from the Cyclop, La Commanderie, Dannemois, France, 1973 © Laurent Condominas. Photo: Laurent Condominas

Exhibition Learning Notes: ‘Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely. Myths & Machines’

This resource has been produced to accompany the exhibition, ‘Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely. Myths & Machines,’ at Hauser & Wirth Somerset from 17 May 2025 – 1 February 2026.

About ‘Myths & Machines’

Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely are reunited in a major site-wide takeover at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, in collaboration with the Niki Charitable Art Foundation. This is the first exhibition dedicated to both artists in the UK and illustrates Saint Phalle and Tinguely’s visionary artistic output and enduring creative collaboration over three decades. Two emblematic figures of contemporary art, Saint Phalle and Tinguely defied conventional artmaking and were fueled with rebellion, in both life and art.

The exhibition takes place as part of Jean Tinguely’s centenary celebrations. To mark this occasion, his innovative and playful oeuvre will be honoured internationally with a range of exhibitions and events.

About Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely

Niki de Saint Phalle (1930 – 2002) and Jean Tinguely (1925 – 1991) were pioneering artists whose collaborative works significantly influenced 20th Century art. Their partnership, both personal and professional, began in the mid-1950s and spanned several decades. Tinguely and Saint Phalle met and started working together in Paris, France, eventually marrying in 1971. The pair forged an extraordinary personal and artistic relationship that resulted in numerous groundbreaking projects that combined their unique artistic visions.

Niki de Saint Phalle was born in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, but spent her childhood in the United States. She was educated at a convent school in New York NY but spent her summers in France. After a tumultuous childhood and a brief career in modelling, she turned to art as a form of self-expression and healing. Saint Phalle was largely self-taught, drawing inspiration from diverse sources, including Antoni Gaudí’s architectural works and indigenous art forms. Her early works included the ‘Tirs’ series (1961 – 1964), in which she created paintings by shooting at canvases embedded with bags of paint, a radical approach that challenged traditional artistic methods. Saint Phalle gained widespread recognition for her ‘Nanas’—large-scale, brightly colored sculptures of female figures that celebrate femininity and fertility. Her most ambitious projects was the ‘Tarot Garden’ (1979 – 2002) in Tuscany, Italy—a sculpture park featuring monumental figures inspired by tarot cards. This endeavour showcased her commitment to creating immersive environments that engaged viewers on multiple levels.

Jean Tinguely was born in Fribourg, Switzerland, and grew up in Basel. He studied at the School of Arts and Crafts in Basel before moving to Paris, France, in the early 1950s. Tinguely became known for his kinetic sculptures, termed ‘Métamatics,’ which were mechanical constructions that incorporated movement and self-destruction, satirizing automation and the technological overproduction of material goods. Tinguely gained international attention with ‘Homage to New York,’ (1960) a self-destructing sculpture performed in the garden of the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York NY. This piece epitomized his interest in the ephemeral nature of art and the fusion of creation and destruction. His works often featured salvaged materials and whimsical designs, engaging audiences in novel ways.

Notable collaborative projects between Saint Phalle and Tinguely include: ‘Hon – en katedral’ (1966), a monumental installation at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden, featuring a giant reclining female figure that visitors could enter; the ‘Stravinsky Fountain’ (1983) near Centre Pompidou, in Paris, France, comprising 16 colourful sculptures inspired by Igor Stravinsky’s compositions; and ‘Le Cyclop’ (1969 – 1994), a monumental sculptural work in the forest of Milly-la-Forêt, France. Their collaborative efforts left an indelible mark on contemporary art, inviting audiences to engage with art in interactive and thought-provoking ways.

Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely in front of their home and studio ‘Auberge du Cheval Blanc,’ Essone region, France, 1967 © 2025 Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All rights reserved. © Shunk-Kender / Roy Lichtenstein Foundation. Courtesy Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in Memory of Harry Shunk and Janos Kender @ J. Paul Getty Trust. Photo: Harry Shunk and Shunk-Kender Photographs

What does the exhibition look like?

In the exhibition, ‘Myths & Machines,’ Saint Phalle’s and Tinguely’s works take over Hauser & Wirth Somerset, marking the first time both artists work has been shown together in the UK.

Beginning in the Farmyard, ‘Le Poète et sa Muse’ (1999) and ‘Les Trois Graces’ (1995 – 2003) are displayed as visitors’ first encounter with Saint Phalle’s iconic ‘Nana’ figures. These sculptures, depicting voluptuous, joyful women in dancing poses, are symbols of femininity and empowerment. Each figure is covered in mirrored glass, a mosaic technique often used by Saint Phalle to harness the physically and personally reflective power of the mirror.

In the Bourgeois Gallery, Tinguely’s iconic kinetic machines occupy the space, ranging from the 1950s to the final years of his life. These assemblage creations such as ‘Deng Xiaoping’ (1989) and ‘Laika’ (1989) showcase his innovative fusion of movement and sound through assemblages of metal, electric motors, and found objects such as wheels, chains and animal skulls. Overlooking these works stands Saint Phalle’s ‘Big Lady (black)’ (1968/1995). By 1965, Saint Phalle began to introduce polyester to create more voluptuous dancing figures that could be displayed in public parks and other outdoor locations, as seen in ‘Les Trois Graces’ (1995 – 2003) that is presented in the farmyard in Somerset.

On view in the Rhoades Gallery, ‘La Grande Tête’ (1988) is a key example of Tinguely’s and Saint Phalle’s creative collaboration, originally an element from ‘La Fontaine de Château-Chinon’ (1988), given to Château-Chinon by former French President, François Mitterrand, which features Saint Phalle’s vibrant sculptures alongside Tinguely’s kinetic elements.

Saint Phalle’s golden furniture is showcased for the first time in the Rhoades Gallery, reflecting her view that art and design are joined, not separate. This collection, comprising thrones, tables, and mirrors crafted from metal, polyester, and gold paint, was originally created as decorative elements for her recently restored film ‘Un Rêve Plus Long Que La Nuit’ (1975). Saint Phalle both wrote and directed this film, featuring performances by herself and Tinguely. Her furniture pieces, Nanas series and ‘Patineuse’ (1966 – 1967) exude a fantastical and fairytale-like quality, aligning with the film’s dreamlike narrative.

Installation view, ‘Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely. Myths & Machines,’ Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2025 © Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Photo: Ken Adlard

Examples of how Saint Phalle pushed the boundaries of traditional artistic techniques are on view in the Pigsty Gallery with her ‘Petit Autels’ (small altars) (1970 – 1972), made in connection with her ‘Tirs’ (shooting paintings) which began in 1961. These works involved embedding paint-filled containers within plaster-covered structures, which Saint Phalle would then ceremoniously shoot with a rifle, causing the paint to burst in a vivid, performative act. The act of shooting these altars can be seen as a symbolic destruction of unjust and oppressive constructs, such as the strictness of the Catholic Church Saint Phalle’s parents raised her in, allowing for the creation of new, liberated forms. This reflects Saint Phalle’s engagement with feminist themes, confronting societal perceptions of femininity and empowerment.

Key examples of Tinguely’s and Saint Phalle’s collaborations are on display in the Workshop Gallery with ‘Nana Dasant (Nana Mobile)’ (1976), the only edition they made together, and ‘Pallas Athéna (Le Chariot)’ (1989). This work relates to the seventh card in the Tarot which appears in Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden in Garavicchio, Italy. These works bring together Tinguely’s kinetic structures of metal and motors and Saint Phalle’s sensual feminine sculptures, whilst still bearing the signature of both artists. A collection of Saint Phalle’s 30 works on paper, never exhibited before, are also shown, reflecting her exploration of personal themes and societal commentary through form, color and composition.

Monumental open-air sculpture, ‘The Prophet’ (1990) is on view in the Oudolf Field amongst the garden’s landscaping. The piece is part of a series created by Saint Phalle whilst in the Tarot Garden in Tuscany, Italy. Tinguely’s dynamic fountains are exhibited, underscoring both artists’ efforts to blend art, movement and the natural world into immersive experiences.

Installation view, ‘Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely. Myths & Machines,’ Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2025 © Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Photo: Ken Adlard

Installation view, ‘Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely. Myths & Machines,’ Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2025 © Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Photo: Ken Adlard

Education Lab: ‘Our Imaginary World’

Taking Niki de Saint Phalle’s philosophy that creativity can serve as a therapeutic outlet and Jean Tinguely’s exploration of movement and transformation through kinetic art, the Education Lab: ‘Our Imaginary World,’ invites reflection on art as a form of healing, self-reclamation and empowerment. In partnership with the East Somerset Federation: Bruton Primary School, Ditcheat Primary School and Upton Noble C of E Primary School, Hauser & Wirth invited 130 young people aged 7 – 8 years to create an installation that, through making gestures of emotional release, spontaneity and imaginative production, connects with the work of both 20th Century artists. ‘Our Imaginary World’ provides an interactive space realized by young people as an exploration of their emotions, experiences and stories.

The Education Lab is part of the gallery’s commitment to inclusive learning programs that instigate a dialogue between art, artists and diverse audiences. Located at our galleries in Downtown Los Angeles, Menorca and Somerset, as well as the Chillida Leku museum, each Education Lab is a collaboration with a local community group, school or university. The interactive spaces take their starting point from one of our international artists, facilitating a platform for discovery, discussion and additional resources.

What are the major themes within the exhibition?

Rebellion

Saint Phalle and Tinguely viewed creation as an act of defiance against established norms. Their works often convey aggressive undertones, challenging societal conventions through bold and provocative expressions. Saint Phalle’s practice is testament to artistic rebellion, intertwining aggressive subtexts with feminist ideals. Her ‘shooting paintings’ invited viewers to participate by shooting color-filled packets with rifles, transforming traditional art into an action-oriented experience. This participatory approach not only garnered significant attention but also aligned with the principles of action painting, emphasizing the physicality of creation.

Central to her work are the ‘Nanas’, vibrant sculptures of female figures that challenge conventional representations of women, positioning them as ‘female warriors’ in the art world. These large-scale creations also assert the capability of female artists to produce monumental works, reinforcing their presence in a domain historically dominated by men.

Tinguely’s kinetic sculptures often incorporated elements of disorder, inviting viewers to engage with the unpredictable nature of his machines. Tinguely not only questioned the role of the artist and the permanence of art but also invited audiences to engage with the transient and often chaotic essence of creation. Collaboratively, Saint Phalle and Tinguely pushed artistic boundaries, embodying a shared commitment to using art as a vehicle for social commentary and transformation.

Healing

Niki de Saint Phalle’s journey of healing through art is deeply rooted in her tumultuous early life and personal challenges. Born into an aristocratic family that faced financial ruin during the Great Depression, she endured a strict upbringing and a traumatic childhood. Following a severe nervous breakdown that led to hospitalization, Saint Phalle began creating collages using pebbles, leaves and found materials. Encouraged by a friend who provided her with gouaches and brushes, she developed a unique style that combined painting and assemblage. Her early works, such as the shooting paintings, served as cathartic expressions of her inner turmoil.

In her later years, Saint Phalle continued to explore themes of healing and self-discovery through monumental projects like The Tarot Garden in Tuscany, Italy, envisioned as a place of reflection and and restoration, described by Saint Phalle as ‘a promenade between nature and culture.’ This process of artistic exploration became a vital means for her to confront and process her emotions, dreams, and traumas, ultimately serving as a therapeutic outlet that facilitated her personal healing and growth. Her life and work continue to inspire discussions on the intersection of art and mental health.

Movement & mechanics

Tinguely’s exploration of movement and mechanics transformed static sculptures into dynamic, kinetic experiences. Tinguely mechanized sculptural assemblages composed of found objects, primarily scrap metal, introducing movement into his art. He referred to these creations as ‘Métamatics,’ emphasising their self-referential nature and challenging conventional notions of art and functionality. Tinguely’s works often incorporated motors and moving parts, inviting viewers to engage with art that was not merely observed but experienced through motion. This integration of movement and mechanics not only expanded the possibilities of sculptural expression but also served as a satirical commentary on the overproduction and mechanisation prevalent in modern society. By infusing his sculptures with movement, Tinguely invited viewers to reconsider their perceptions of art, technology and the mechanized world around them, bringing freedom and life to machines. As Tinguely remarked, ‘le movement c’est la vie (movement is life)’.

Myth & fantasy

Saint Phalle’s and Tinguely’s creative practices were imbued with fantasy and myth. Saint Phalle often immersed herself within the very sculptures she crafted, transforming these spaces into imaginative worlds that were creatively liberating. In her early drawings, Saint Phalle wove together vibrant, interlocking scenes populated by recurring motifs—fantastic creatures, fairytale landscapes and real-life imagery like cars, planes and skyscrapers—drawing inspiration from her environment and mythology. She wrote plays and films that built upon these motifs and fairytale landscapes, with a young girl as the heroine.

Tinguely’s kinetic sculptures were not merely machines but whimsical creations that invited viewers into a playful, imaginative world. Tinguely’s work often incorporated sound, transforming everyday materials into fantastical entities. This imaginative world-building through sculptural reinvention invited viewers into a universe where fantasy and reality coalesced. This shared commitment to fantasy and imaginative expression was a cornerstone of both artist’s collaborative work to createimmersive environments.

Installation view, ‘Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely. Myths & Machines,’ Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2025 © Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Photo: Ken Adlard

Installation view, ‘Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely. Myths & Machines,’ Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2025 © Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Photo: Ken Adlard

How did the artists make their work?

Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely’s collaborative making process was characterized by a dynamic interplay of materials, techniques and shared visions. Saint Phalle and Tinguely’s collaboration began with Saint Phalle’s request for Tinguely to construct an iron armature for her first sculpture in 1958. This initial collaboration evolved into a ‘four hands’ approach, where they alternated roles in the creative process. Saint Phalle would prepare, glue and paint, while Tinguely added elements like bent wires, resulting in unique assemblages that blended their individual styles.

Other artists and movements to consider

Louise Nevelson (1899 – 1988) was an American sculptor known for her monumental, monochromatic, wooden wall pieces and outdoor sculptures.

Nouveau réalisme was founded in 1960 by art critic Pierre Restany and painter Yves Klein as an artistic movement that sought to bridge the gap between art and everyday life, incorporating real objects and materials into artworks to challenge traditional distinctions between art and reality. Both Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely belonged to the nouveau réalisme art movement.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889 – 1943) was a Swiss artist who defied categorization during her brief career as a painter, sculptor, architect, performer, choreographer, teacher, writer and designer of textiles, stage sets and interiors, reflecting her commitment to abstraction and innovative forms. She is considered a pioneer of constructivist art.

Louise Bourgeois (1911 – 2010) is recognized as one of the most important and influential artists of the 20th Century. Her career spanned over 70 years, during which time she employed a wide variety of working methods and materials, across genres of drawing, printmaking, painting, sculpture and textiles

Hans Arp (1886 – 1966) is a key figure in art history who focused his attention on everyday objects. He created biomorphic work whose organic forms highlighted his fascination with processes of procreation, growth and death. He studied the mineral, vegetable and animal worlds for creative inspiration.

Jason Rhoades (1965 – 2006) was an American artist for whom sculpture and myth were intertwined forms of construction. His epic assemblage installations established him as a force of the international art world in the 1990s.

Installation view, ‘Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely. Myths & Machines,’ Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2025 © Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Photo: Ken Adlard

Glossary

Action painting is a style within abstract expressionism that emphasizes the physical act of painting itself, characterized by spontaneous techniques such as dripping, splattering and vigorous brushstrokes to convey movement and emotion.

Assemblage is an art form that involves creating sculptures by combining various three-dimensional elements, often found objects, into a single composition, thereby transforming everyday items into new artistic expressions.

Feminism is a movement advocating for the rights and equality of women, aiming to address and rectify gender-based disparities in various societal domains

Freedom is the power or right to act, speak, or think as one wants.

Humor is the quality of being amusing or comic, especially as expressed in literature or speech. It is also a mood or state of mind

Kinetic art incorporates movement as part of its expression, either mechanically, by hand, or through natural forces, engaging viewers through dynamic interaction.

Métamatics refers to a series of kinetic sculptures created by Swiss artist Jean Tinguely in the late 1950s, designed as machines that produce abstract drawings when activated by viewers, challenging traditional notions of authorship in art.

Nana is a French colloquial term for a girl or woman, similar to ‘lass’ or ‘chick in English.

Tarot is a set of 78 cards, comprising 22 major arcana cards depicting symbolic imagery and 56 minor arcana cards divided into four suits, traditionally used for fortune-telling and gaining insights into the past, present, or future.

Tir is the French word for ‘shooting,’ derived from the word ‘tir,’ meaning to fire. In the context of Niki de Saint Phalle’s work, it refers to her ‘shooting paintings,’ where viewers were invited to shoot at canvases filled with paint-filled bags.

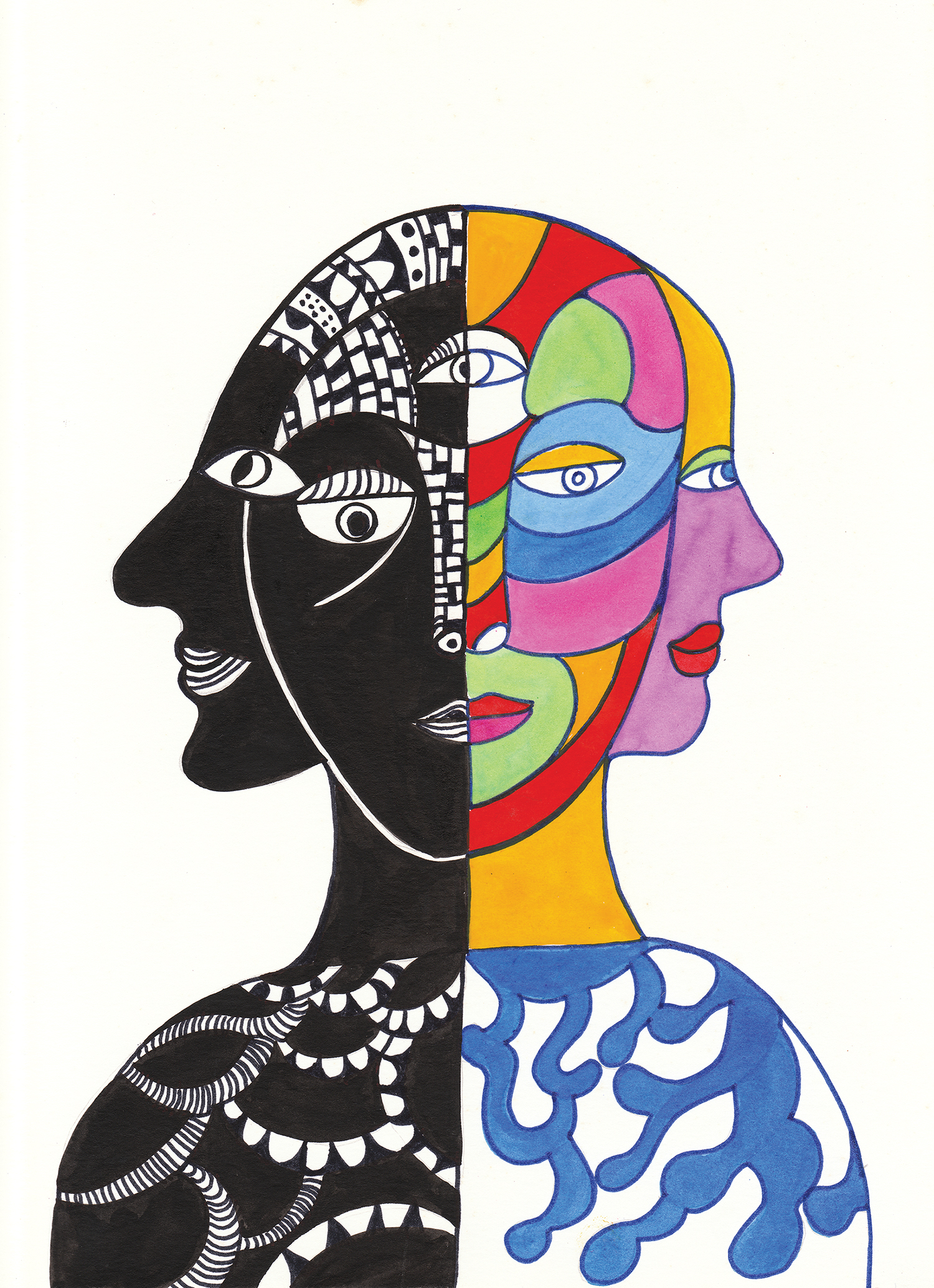

Niki de Saint Phalle, Double Tête, 1999 © Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All rights reserved. Photo: NCAF Archives

Discussion questions

Key stages 1 – 2

Saint Phalle used everyday objects in her art. What do you understand to be art materials? Discuss your answers.

Some artworks, like those created by Jean Tinguely, can move. How do you think moving art is different from still art? How does movement change the way you experience an artwork?

Key stages 3 – 4

In what ways do their works invite viewer participation, and how does this engagement alter the experience of the artwork?

Some of Saint Phalle’s and Tinguely’s artworks are displayed outdoors. How do you think placing art in a park, garden or public space changes the way people experience it? Where would you display your own outdoor sculpture, and why?

GCSE and A-Level

How does the collaboration between Saint Phalle and Tinguely challenge traditional notions of individual artistic authorship?

Reflect on the balance between mechanical elements and organic forms in Saint Phalle’s and Tinguely’s collaborative pieces. How does this interplay influence the overall impact of their work?

Creative activities – During your visit

Inspired by Tinguely’s kinetic sculptures, design your own moving artwork. Consider the materials you would use and how each piece would move. Create a drawing or model of your design.

Saint Phalle’s ‘Nanas’ are symbols of female empowerment, femininity and motherhood. Using found objects and collage materials, create your own ‘Nana’ that embodies the qualities and impact of a significant female figure in your life—be it a family member, mentor, friend or public figure. Consider poses, colors and textures that reflect your relationship with them.

Creative activities – After your visit

Imagine one of Saint Phalle’s sculptures or Tinguely’s machines comes to life. What adventures would it have? How would it speak? What would it say? Write a short story about its journey.

Saint Phalle and Tinguely often worked together to create art. Think of a project you could create with a friend that combines two different art styles or materials. What would your collaborative artwork look like?

Think of an object from your home that holds personal significance. Imagine transforming it into a piece of art, much like Saint Phalle and Tinguely transformed everyday items. Draw your envisioned artwork and write a brief story about its significance.

Resources

1 / 10