Jenny Holzer: Softer Targets

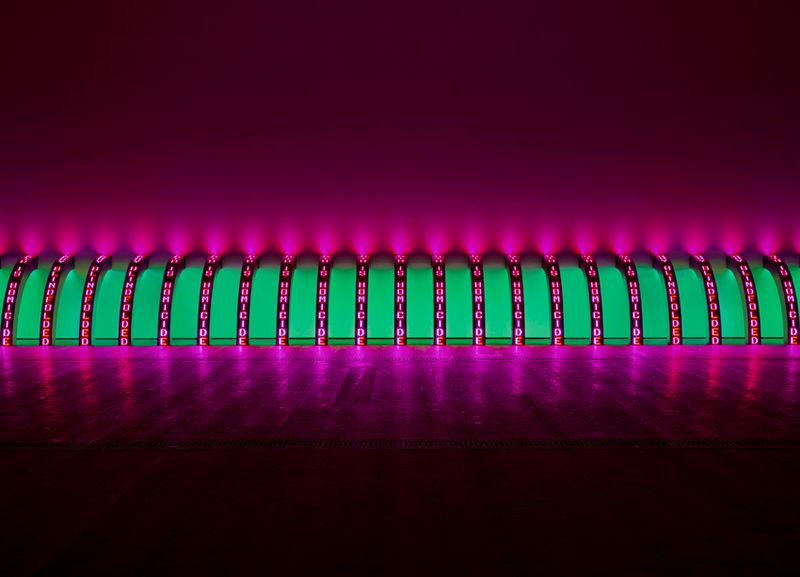

Installation view, 'Jenny Holzer: Softer Targets', Hauser & Wirth Somerset, England, 2015. Photo: Ken Adlard

Jenny Holzer: Softer Targets

This resource has been produced to accompany the exhibition ‘Jenny Holzer Softer Targets’ at Hauser & Wirth Somerset.

It provides an introduction to the artist Jenny Holzer, identifies the key themes of her work and makes reference to the historical and theoretical contexts in which her practice can be understood. It offers activities, which can be carried out during a visit to the gallery, issues for discussion, additional research and a list of related education activities held at the gallery during the exhibition.

Photo: Nanda Lanfranco

Jenny Holzer was born in 1950 in Ohio, USA. She studied painting and printmaking (BFA) at Ohio University, and received an MFA in painting from Rhode Island School of Design in 1977.

In 1976 Jenny Holzer moved to New York and enrolled in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Independent Study Programme (ISP).

Much of Jenny Holzer’s education was in the Liberal Arts and she believes this broad education impacted the work she made. Although much of her work focused on painting, she was already using text in her pieces at an early stage. Holzer works with language as an artistic medium, employing it across a variety of formats, from printed posters to LED displays. ‘I used language because I wanted to offer content that people – not necessarily art people – could understand’, she has said. Her work is part of the public domain, equally accessible in museums and galleries as in storefronts, on billboards and T-shirts, and even electrified in New York’s Times Square.

Her text pieces started in the 1970s with the New York City posters, a series she called Truisms, and she credits her breakthrough to ‘putting up anonymous street posters around lower Manhattan. Dan Graham, an artist I admire, noticed them, talked to people about them, and finally figured out that I was the person doing them. So thank you, Dan.’1

In the 1980s Holzer began using LED lights and electronic billboards on public buildings and monuments, in place of her posters. One example from 1986 was the presentation of lines from her text series Survival, including her famous sentence ‘PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT’ on the 20 x 40 foot Spectacolor electronic sign board in New York’s Times Square. Other big projects included a giant installation of LED displays spiralling up the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s atrium.

In 1990 Holzer became the first woman to represent the USA with a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale, for which she was awarded the Golden Lion prize.

Since 1996 Holzer has been using light projection – in which a powerful film projector casts scrolling texts onto architecture or a landscape – as another way of presenting texts in the public realm. The texts and light are dramatic but unobtrusive, adapting to varied projection surfaces, from the mountains and ski jump in Lillehammer to the Pyramide du Louvre in Paris.

Other significant series of works, after the early Truisms are Inflammatory Essays (1979 – 1982), Living (1980 – 1982), and Survival (1983 – 1985). In recent years Jenny Holzer has returned to painting, making reference to Abstract Expressionism and Suprematism and reinforcing the continued relationship of art with politics.

"Jenny Holzer – Portrait of the Artist", https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/feb/05/jenny-holzer-portrait-artist

Working Methods

Jenny Holzer is best known for making visual art utilising language. Throughout her career as an artist, she has employed the power of words: text carved into stone, in LED lights, cast into metal plaques or projected onto iconic buildings like The Louvre in Paris (2009), City Hall in London (2006) and Tate Liverpool (2003).

The subject of text and images has a longstanding relationship within the history of art. Generally, works of art are given titles, which provide viewers with clues or pointers to the works’ interpretation. However, since the twentieth century the relationship between the artwork and its title has become far more complicated.

A more theory-driven art world has put greater emphasis on the written word. From Picasso to Holzer, we have seen text as both content and a compositional element, in the work of the Cubists, in Dada, and in Conceptual Art.

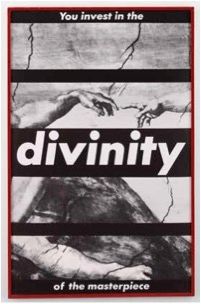

Early in her career, Jenny Holzer considered many different career paths such as writing and law before practicing as an abstract painter. However, starting in the 1970s, in order to make more explicit statements and to establish more direct contact with a larger audience than would visit galleries, she changed her working methods. With her first series, Truisms, Holzer began to use text in a bold and dramatic manner. Her text as art has appeared on posters, billboards, T-shirts, metal plaques, park benches, television and projections on and in buildings, such as airports and cathedrals. Partly shaped by her association with Collaborative Projects (Colab), a group of New York City artists that aimed to collaborate on work directed to the needs of the community at large, Holzer reached a mass audience by displaying work outside the gallery setting and employing tactics usually used by the media. These approaches raised interesting questions about the power of art outside its traditional context; it challenged traditional ideas about authority and authorship. These issues were not exclusive to Jenny Holzer’s work but seen in the work of other American artists at the time, such as Barbara Kruger, Keith Haring, Claes Oldenburg and Nam June Paik.

Jenny Holzer’s LED pieces have a minimal aesthetic, similar to the works of Donald Judd, and recall the luminosity of a Dan Flavin sculpture from the same era, but they are accompanied by text. In the Threshing Barn, the first of the gallery spaces, the viewer encounters ‘MOVE’, a new eight-foot LED work suspended from the rafters in vivid juxtaposition to its surroundings. The slender, four-sided LED column senses the presence of the visitor and moves in response. The text displayed on each side of the column comes from declassified and other sensitive U.S. government documents.

Jenny Holzer, from 'Truisms' (1977 – 1979), 1983. © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Jenny Holzer from Survival (1983 – 1985), 1985. © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: John Marchael

Several of Holzer’s stone benches are exhibited in and around the galleries. At first they may remind you of cemetery furniture, especially as many of their titles begin ‘Memorial Bench’ or ‘Living Series’, but they may also evoke garden furniture or public seating, offering a place for people to sit and talk. Jenny Holzer began working in stone in 1986. Rather than one particular stone, she uses various types including marble, granite, sandstone and limestone. She is drawn to the beauty of the stones and to the use of a material often employed in ancient monuments and war memorials; the marking, colouration and significance of the material are important to her, as is, of course, the carving of the text that they display.

Many of the pieces on display deliver messages from Living and Survival; they appear to be less direct than the Truisms, offering a selection of observations, directions and warnings. The way in which they are written often refers to ‘you’, the reader, and identifies situations where you respond to your social, physical or psychological environment.

Jenny Holzer, 'Purple', 2008. © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

The enamel metal signs are all hand-painted, and the metal plaques are cast in bronze or aluminium. When they are installed on the exterior walls of the gallery, they may remind you of the signs that often appear on historic buildings. This reinforces their sense of authority; they have a voice of control but often surprising content.

‘Lustmord Table’ (1994) is a work conceived in response to conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, and to the targeting of women and girls as a tactic of war. It features the ‘Lustmord’ text, which Holzer wrote from 1993 – 95 after being invited by Süddeutsche Zeitung, a national newspaper in Germany, to contribute to their weekly supplemental magazine. The German word ‘Lustmord’ is made from two words: ‘Lust’, which means desire, and ‘Mord’, which means murder.

Jenny Holzer, 'TURN SOFT', 2011. © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Ken Adlard

Jenny Holzer, 'Lustmord Table', 1994. © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights had begun recognising crimes against women, such as rape, as human rights violations. On the wooden table are many carefully displayed human bones. On the bones there are engraved silver bands. The process of engraving onto bands rather than directly onto the bones may remind one of bird bands or bangles, where initials or a significant sentence rest against the skin. But here there is no skin, only bones; this use of the human body reminds us that people were hurt in ways beyond the physical, and it continues Jenny Holzer’s theme of war, power and pain.

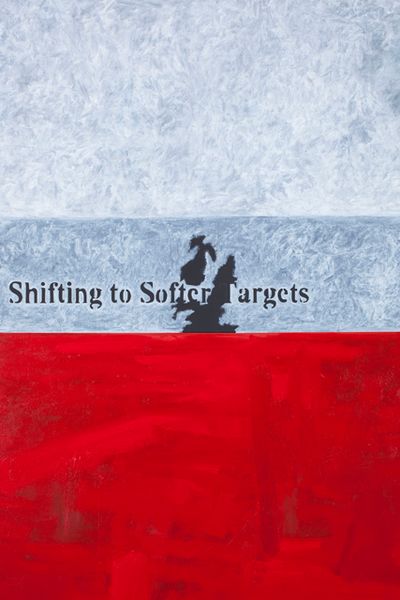

In her recent paintings from 2005, Holzer works in a more traditional way, employing oil paint and linen. Since 2004 she has used U.S. government documents as a source for her work. Her paintings present pages from these documents in large scale, continuing her focus on politics and power.

The paintings appear a little like Abstract Expressionist or Colour Field paintings, or possibly could be seen as responding to the early twentieth century Suprematist works of the Polish-Russian artist Kazimir Malevich. However unlike these earlier movements in politically charged abstract paintings, Holzer’s paintings are faithful reproductions of existing documents, such as the hand- painted words ‘secret’ or ‘Shifting to Softer Targets’ that break up the abstraction.

A recent exhibition of Holzer’s paintings was titled ‘Dust Paintings’, a reference to her process – she and the team of painters with whom she works, carefully trace and paint the text by hand, echoing traditional Arabic calligraphy, which can involve extremely fine work called Ghubar or dust in Arabic.

Jenny Holzer, 'Shifting to Softer Targets' (detail), 2014 – 2015. © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Themes

Truisms and Inflammatory Essays

Jenny Holzer is famous for her short statements that she calls Truisms. She wrote these single-line statements to resemble existing truisms, maxims and clichés. Each line from Truisms distills difficult and contentious ideas into a seemingly straightforward fact or aphorism. Some of the sayings include:

‘A MAN CAN'T KNOW WHAT IT'S LIKE TO BE A MOTHER’

‘MONEY CREATES TASTE’

‘ENJOY YOURSELF BECAUSE YOU CAN'T CHANGE ANYTHING ANYWAY’

‘FREEDOM IS A LUXURY NOT A NECESSITY’

‘DON’T PLACE TOO MUCH TRUST IN EXPERTS’2

Jenny Holzer’s work presents both clear statements and minimal or conceptual aesthetics that make straightforward comments about society today. By working in such a familiar medium, she invites us to question the mass information we encounter daily in contemporary society, particularly via politics and journalism. She wants her work to be something that you just happen to notice, rather than something you immediately read as art.

The wide range of subjects tackled by the Truisms was inspired by the reading list Holzer received at the Whitney Independent Study Program. These one-line statements offer a good format for Jenny Holzer to make observations on almost any subject. The content of each Truism has the capacity to instantly become topical. However, in her second series, known as Inflammatory Essays, the content is often longer and addresses what could be seen as more contemporaneous issues.

In contrast to the Inflammatory Essays, which consist of paragraphs of text, each containing 100 words arranged into 20 lines, Truisms were statements confined to a length of one line which were either displayed together on a poster or broadcast as scrolling text on an LED display.

The tone of Inflammatory Essays is intentionally more aggressive and challenging. The essays were influenced by Holzer’s readings of political, artistic, religious, utopian and other manifestos. Although Holzer has put the texts together, they do not necessarily reflect her personal views. Her writing often considers issues from multiple viewpoints but tackles the issues that are clearly important to many people, a little like graffiti – when located in the city, they cannot go unnoticed.

Many of the works in this exhibition, such as the bronze plaques, are from the Living series (1980 – 1982), in which Holzer presents a set of quiet observations, directions and warnings. Unlike the Inflammatory Essays, the Living texts are written in a matter-of-fact style, suitable for descriptions of everyday life. The commentaries touch on how the individual negotiates landscapes, persons, rules, expectations, desires, fears, other bodies, one’s flesh and oneself.

https://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/contemporary/Jenny-Holzer

Jenny Holzer, 'Truisms' (detail), 1983. © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Text as Image / Image as Text

Throughout history, we have considered the balance of power between text and image, and in society we still ask whether the word is as powerful as the image.

Since Modernism, artists, philosophers and theorists have intellectualised this debate, so much so that we can see its impact in movements such as Cubism, Dadaism, Futurism, Pop Art, Conceptual Art and Postmodernism. It was in the late twentieth century that society was described as a battlefield of text and images all fighting for our attention. Many artists were said to manipulate these languages, so that popular culture’s ‘ideological effects become transparent’.3

It is within this environment that Jenny Holzer’s use of text comes into its own, under the guise of a public service message. She addresses subjects such as sex, death and war, and blurs the boundaries between art and society; her messages reinforce the problems of a society that dumbs down serious and significant issues and responsibilities. The use of simple, clear language presented in the latest technology breaks away from previous uses of language in art and speaks to a contemporary audience. It is minimal and simple; she wants it to project a voice of authority, which raises an interesting gender issue. Holzer has developed a deliberately anonymous, powerful and political voice.

3. Benjamin Buchloh, ‘Allegorical Procedures: Appropriation and Montage in Contemporary Art’, Artforum 21, Sept. 1982, pp. 43–56.

Jenny Holzer, 'Water board black white', 2009. © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Political Art

Jenny Holzer’s art has a political tone because she asks questions about the role of the individual in society and draws attention to the differences between the private and the public in society. If she were to make painted representations of her subjects they would probably be narrative images, like the work of Leon Golub. The works of both Golub and Holzer make direct reference to our individual desires and wider social expectations in an authority-driven society.

However, the use of text and language provides Holzer with a direct or explicit method of communication rather than a painted image. She feels that by using words, people will have a more immediate understanding of her subject.

Through her choices of statements and the minimal way in which they are presented, Jenny Holzer takes the personal out of her work. The statements become divorced from her, the artist; they are not her words but a shared voice or many voices. Therefore, the public location is highly important; she wants people to read the signs when they have time to think about them, or to stop and notice them because they make them angry or reinforce their own personal position. Her texts can help to define beliefs, calm people down or make people aware that there are limitless opinions available to them.

Her web project ‘Please Change Beliefs’ allows users to improve or replace lines from her Truisms series.

Holzer says, ‘I want the meaning to be available but I also want it sometimes to disappear into fractured reflections or into the sky. Because one’s focus comes and goes, one’s ability to understand what’s happening ebbs and flows. I like the representation of language to be the same. This tends not only to give the content to people, but it will also pull them to attend.’4

Following 9/11 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Holzer wanted to know more about what was happening and began making work that specifically responded to those wars. In particular, in her recent paintings, she has used documents that have been drawn up and redacted by the government, such as policy memos, statements by American soldiers and autopsy reports from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. These paintings share the power of her text pieces but are more concerned with the content taken away than the content displayed. Coloured or black blocks of paint conceal large amounts of text, revealing single words distributed across the redacted canvas, providing an unclear indication of their content. Although Holzer’s position is not clear, the paintings make us question the relationship between art and politics, politics and the citizen, as well as policy and ethics. They remind us of the continued uncertainty of moral and ethical values in the world, despite having well-established international institutions.

4. Kelly Shindler, ‘Art in the Twenty First Century’, 2007, see clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CxrxnPLmqEs

Barbara Kruger, 'Untitled (You Invest in the Divinity of the Masterpiece)', 1982, The Museum of Modern Art, New York Barbara Kruger, © 2006. Digital image, MOMA, New York / Scala, Florence. © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Jenny Holzer, 'Hanging', 2014. © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Feminism

Jenny Holzer is often seen as belonging to a generation of feminist artists whose work emerged in New York in the 1980s, including Barbara Kruger, Rosemarie Trockel and Cindy Sherman. All of these artists make art that comments on personal and shared identity within a broader political context. For example, Cindy Sherman uses photography to represent a range of identities; the model behind all of her images is herself, so none of the women she represents are real, although they do exist as characters or cultural types. This work reinforces the relationship between fact and fiction in society, and the relationship between the artist and her work.

As so much of the language that Jenny Holzer uses derives from positions of power and authority in society, it challenges notions of patriarchal order. Her Lustmord series focuses on murder, rape and justice, and the Truisms purposefully assume the subject to be female: ‘A MAN CAN’T KNOW WHAT IT’S LIKE TO BE A MOTHER’. The choice to make public work reinforces Jenny Holzer’s political message; by speaking to a larger audience she contributes to a call for social change. This has always been the force of the Feminist movement, along with challenging the traditional spaces in which art is shown and the media out of which art can be made.

Jenny Holzer: Works

Truisms (1977 – 1979)

The Truisms series (over two hundred fifty single sentence declarations) was written by Holzer to resemble existing truisms, maxims and clichés. The series was influenced by the reading list provided by Ron Clark at the Whitney Independent Study Program, where Holzer studied in 1976 / 77. Each truism distills difficult and contentious ideas into a seemingly straightforward fact.

Privileging no single viewpoint, the Truisms examine the social construction of beliefs, mores and truths. When they are displayed in serial format, Holzer organizes the aphoristic statements in alphabetic order. The Truisms first were shown on anonymous street posters that were wheat-pasted throughout downtown Manhattan, and subsequently have appeared on T-shirts, hats, electronic signs, stone floors and benches.

Inflammatory Essays (1979 – 1982)

Influenced by Holzer's readings of political, artistic, religious, utopian and other manifestos, the Inflammatory Essays are a collection of 100-word texts that were printed on colored paper and posted throughout New York City.

Like any manifesto, the voice in each essay urges and espouses a strong and particular ideology. By masking the author of the essays, Holzer allows the viewer to assess ideologies divorced from the personalities that propel them. With this series, Holzer invites the reader to consider the urgent necessity of social change, the possibility for manipulation of the public, and the conditions that attend revolution.

Living (1980 – 1982)

In the Living series, Holzer presents a set of quiet observations, directions and warnings. Unlike the Inflammatory Essays, the Living texts are written in a matter-of-fact, journalistic style, suitable for descriptions of everyday life. The commentaries touch on how the individual and his or her body negotiates landscapes, persons, rules, expectations, desires, fears, other bodies, one's flesh and one's self. The Living writing appeared on cast bronze plaques, of the sort that often appear on historical buildings, to lend the writing authority. The writings were also incorporated into hand painted signs.

Survival (1983 – 1985)

Survival is a cautionary series where each single sentence instructs, informs or questions the ways an individual responds to his or her political, social, physical, psychological and personal environments. The tone of Survival is more urgent that that of Living. The Survival texts were the first to be written especially for electronic signs; the sentences are short and pointed so as to be easily available to passersby. ‘PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT’ is a key Survival text.

Under a Rock (1986)

Holzer's Under A Rock explores the unmentionable as well as pain’s manifestations and persistence. The effect of politics on the flesh is one theme of the series. Under a Rock was composed for electronic signs and stone benches, and the inaugural exhibition was the first instance in which Holzer created an enveloping indoor environment for her work.

Laments (1989)

Written during the bleakest insurgence of the AIDS epidemic, the Laments chronicle unnecessary death in the first-person voices of the unknown and unnamed who suffer. Written from the viewpoints of women, men, children and an infant, the Laments first were shown at the Dia Art Foundation on thirteen stone sarcophagi and in thirteen vertical synchronized LED signs.

Mother and Child (1990)

Created for the Venice Biennale where Holzer was chosen as the United States representative, Mother and Child outlines fear for a newborn and the forms it inhabits. With autobiographical currents (Holzer's daughter was born in 1988), the complete text was programmed on twelve vertical LED signs and cut into a marble floor in the American pavilion.

War (1992)

The War series began during the first Gulf conflict. With accounts of the savageries and results of war relayed frankly, the series casts an eye on the moments of anguish whose totality is war. Vertical LED signs programmed with the series made the stairs of the Kunsthalle Basel impassable (1992). The Nordhorn Black Garden (1994), an anti-memorial, has the text inscribed on five sandstone benches.

Lustmord (1993 – 1995)

At the invitation of the Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, Holzer created a series that was prompted by the war in Bosnia (where the rape of women was a war tool and strategy) but deals with sexual violence in its ubiquitous manifestations. Lustmord is written from the vantage points of the perpetrator, the victim and the observer of a violent sexual encounter or its aftermath. For Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, the texts were handwritten on the skin of women and a man and photographed in close-up. A folded white card was glued onto the cover of the magazine. Printed with ink partially made of blood donated by women from Germany and the former Yugoslavia, the cover card contained all three voices. The texts have been incorporated into electronic signs. They also have been engraved in silver bands that were then wrapped around human bones and methodically laid out on worn wooden tables.

Erlauf (1995)

Commissioned to make a peace monument in Erlauf, Austria, Holzer created a series that treated war and its implications. Brief fragments of thought that describe an action or observation, Erlauf treats war as an authorless compendium of fractured memories, events, disruptions and questions. The permanent installation in Erlauf, Austria, is comprised of a fixed searchlight that can be seen miles away submerged in a granite base. Surrounding the searchlight are white plantings and granite pavers inscribed with selections from Erlauf. Like all of Holzer's series Erlauf has been included in other media, including LED signs.

Arno (1996)

Begun as an account of losing someone to AIDS, Arno, more expansively, treats living with the death of one who was loved. A version of the text made its debut in a music video for Red, Hot and Dance, an AIDS fundraiser. The writing was completed, and made general, so as to treat anyone's loss after a great and terrible love. Arno was next presented to the public as a light projection on the Arno River in Florence, Italy, in 1996. This projection on the Arno was Holzer's first, and this medium has been crucial to Holzer's practice since.

Blue (1998)

More lyrical and obliquely narrated than Holzer's earlier works, Blue touches on the pervasive fallout of abuse and bad sex. The text examines how individual memory can be situated next to and within unnamed but global catastrophe. By addressing and eliding individual and mass trauma, this text indicates that no disaster is purely local but leaks into the world’s political and psychological groundwater.

OH (2001)

Written during Holzer's residency at the American Academy in Berlin, OH was first displayed in the installation Holzer created specifically for Mies van der Rohe's Neue Nationalgalerie. Thirteen LED signs designed for the ceiling of the museum emit light and texts that viewers crane their necks to scan, or drop to the floor and their backs to read. The text treats motherhood, violence, love, the past, the future, the dreadful and the tender.

Suggested Activities

In small groups walk around the whole exhibition and make a record of the types of Jenny Holzer artworks and the range of materials that they are made from. How do you think that the material the artwork is made from affects the emotional content of the work?

Jenny Holzer said that she wanted to deal with explicit subjects but did not want to make figurative paintings, so she chose to use words instead. Think about an issue you would like to communicate as an art work – what would be the best way for you to visualise it and why?

In a small group or pair, walk around the exhibition and collect key words that appear a lot in Jenny Holzer’s work. Use these key words to make up your own phrase or sentence.

Reflecting on Jenny Holzer’s Truisms think about your own position and place in society today – is there a Truism that is most meaningful to you? Can you make up your own?

Discussion Questions

Do you think that Jenny Holzer’s work is Feminist? Discuss reasons for your

How does art make you politically aware? Think of some

What emotions do the texts in Lustmord evoke in you?

How do Holzer’s Truisms work in promoting social change?

How does protest become art?

Do you consider what Holzer does as art?

Do you think it can still be considered Jenny Holzer’s artwork even if the text comes from a different author?

In what ways is public art similar to performance art?

Supplementary Research

‘Jenny Holzer (Contemporary Artists Series)’, 2001, Samuel Beckett, Elias Canetti & Jenny Holzer, Phaidon Press

‘Jenny Holzer’, 2009, Elizabeth A. T. Smith, Hatje Cantz Verlag Gmbh

‘Jenny Holzer: Endgame’, 2012, Dirk Skreber, Distanz Publishing Jenny Holzer website: www.jennyholzer.com

Jenny Holzer interview with Kiki Smith: https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/jenny-holzer/

‘Blasted Allegories: An Anthology of Writings by Contemporary Artists’, 1989, Brian Wallis, MIT Press Culture Show – Interview with Jenny Holzer

GLOSSARY

Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionism can be loosely described as a movement consisting of two groups: Colour Field painters who covered their canvases with swathes of rich colour and action painters who poured and spattered paint to create their artworks. This includes the work of Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and Jackson Pollock.

Conceptual Art

Conceptual art is a movement developed in the 1960s that was concerned with the idea or concept of the artwork more that the aesthetic appearance of it (what it looks like or how it is made).

Cubism

Invented by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in around 1907 / 8. Cubism was an attempt to record different views of subjects (often still life or figures) in one painting. The work has a fragmented, facet-like abstract appearance.

Dadaism

The European avant-garde developed this movement at the beginning of the twentieth century, especially in Zurich and Berlin. Dada artists wanted to create new forms of art, performance and poetry and made direct reference to the modern world, through newspaper, film and adverts from contemporary life.

Digital Art

Since the 1970s artists have often been working with computers and multi-media, this type of practice is often called new media art or digital art.

Feminist Movement

Since the 1960s the feminist art movement and feminist theory have developed to reflect women’s lives and experiences. Jenny Holzer’s work deals with a range of politics, drawing attention to positions of power in society; feminism is one way of addressing this.

Futurism

Established by a radical group of Italians in 1909, Futurism like other avant-garde movements, rejected the old, and wanted art to represent the modern world of industry and technology.

Installation

Art that is produced for a specific place for a specific period of time is often referred to as an installation. It may be an environment that you have to walk through, or behave in a certain way to access it, or it could be something that you have to look at from a certain position.

LED

LED stands for a light-emitting diode, commonly used in digital clocks and other small devices. LEDs allow for text, video display and advanced digital communications technology.

Minimalism

Minimalism emerged as a reaction to the gestural work of Abstract Expressionist painting. Instead of bold swathes of colour, Minimalism relied on an industrial and anonymous aesthetic, focusing on the materiality or structure of the work rather than any emotional content.

Patriarchal Order

The order of a social society, which is based on the male having control or primary power, for example a male politician, or father as the head of a family.

Postmodern

Postmodernist is a way of describing cultural movements and styles since the 1960s. It is often described as demonstrating a blurring of the boundaries between high and low culture. It does not recognise a single authority, style or method of working. In this case, like Jenny Holzer’s work, it erodes the distinction between art and everyday life.

Public Art

Any art that is exhibited in a public space, outside or in a publically accessible building is known as public art. It often reflects a community collaboration or commission and is usually site-specific. In this context the relationship between the artwork and the audience is just as important as its location.

Site-specific

An artwork produced for a specific location is referred to as site-specific. The site or location is part of the work’s meaning, therefore if it were removed from that location it may lose part of its meaning.

Suprematism

The Suprematist movement is the name given by the Russian artist Kazimir Malevich to the abstract art he developed from 1913 which included basic geometric forms, such as squares, lines and rectangles painted minimally often in monochrome.

Truism

A truism describes a statement of truth, something that cannot be contested, as it is an accepted fact.

Image credits: Jenny Holzer works © 1981 – 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Resources

1 / 10