Announcing Representation of the Estate of Carol Rama Alongside Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin

Carol Rama in her studio, 1997. Photo: Pino Dell’Aquila

Announcing Representation of the Estate of Carol Rama Alongside Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin

We are pleased to announce representation of the Estate of Carol Rama alongside Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin. Over more than seven decades, Carol Rama (b. 1918, Turin; d. 2015) developed a radical body of work that addressed connections between desire, sacrifice, eroticism and repression. By constructing a visual cosmos where transgression leads to liberation, Rama countered assumptions about gender, sexuality and representation, offering a retort to the societal conventions and the prevailing far-right political ideologies that defined the fascist-dominated Italy of her youth. She set neither boundaries nor hierarchies between painting, drawing, sculpture and printmaking, pulling all of these mediums into her image universe. ‘My self-assurance exists only across from a sheet of paper that needs to be filled in,’ Rama once declared. ‘Work is the only way to drive off my fears. My rebellion consists of painting.’

Today, Rama is considered one of the most original and individualistic artists to emerge from the 20th Century. Yet while she exhibited regularly in Italy, her work was largely absent from international contemporary discourse until the late 1990s when it finally attracted interest among a new generation of artists, curators and critics. Rama’s art has since galvanized ever-expanding attention and avid scholarship. She was awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 2003 and major solo exhibitions of her work have been presented at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1998); MACBA, Barcelona (2014); Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, Paris (2015); New Museum, New York City (2017); and Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt (2024), among others.

Carol Rama’s first solo exhibition with Hauser & Wirth will open in May 2026 in New York.

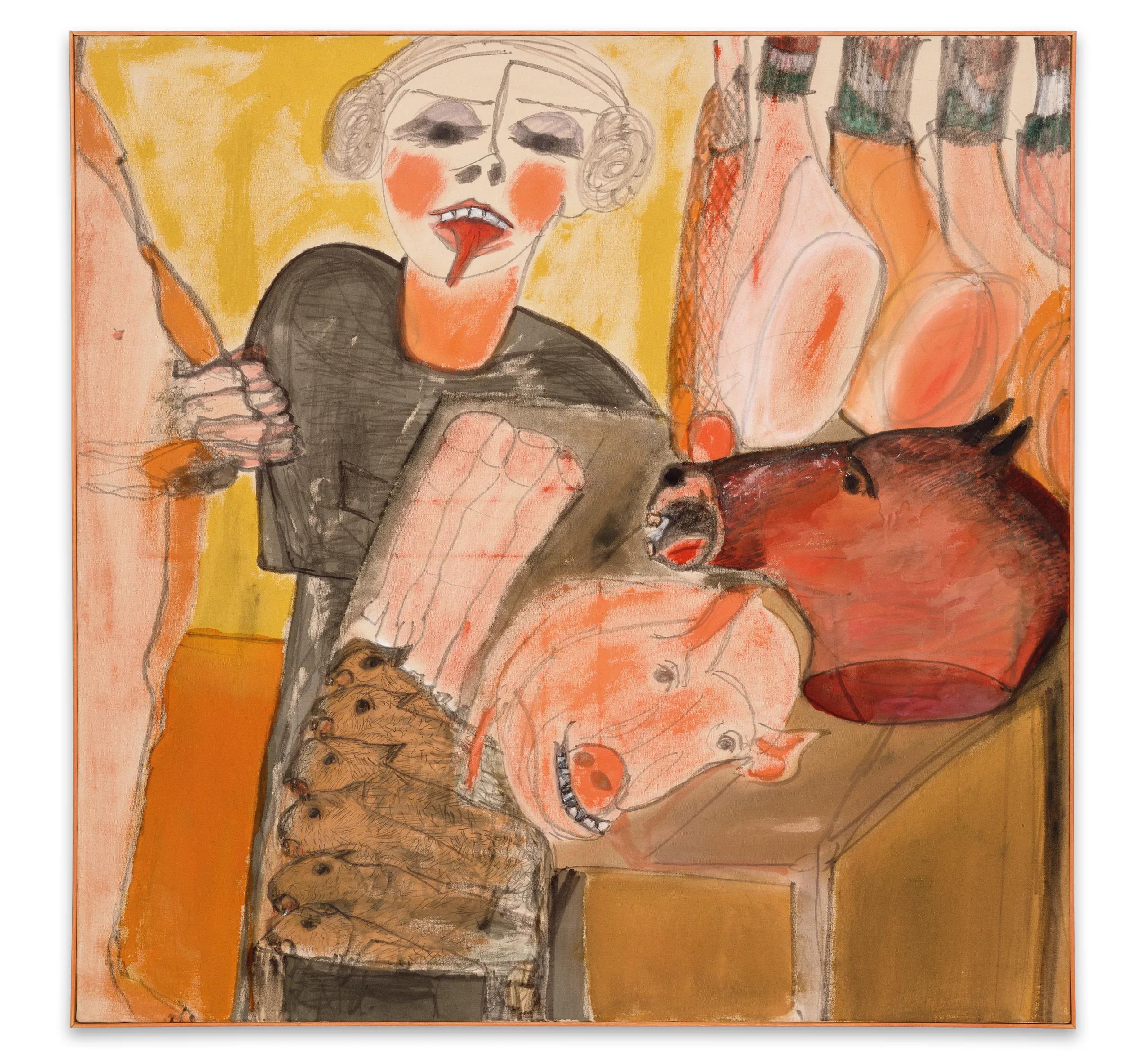

Carol Rama, La macelleria (The Butcher’s), 1980, Private Collection © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino. Photo: Pino Dell'Aquila

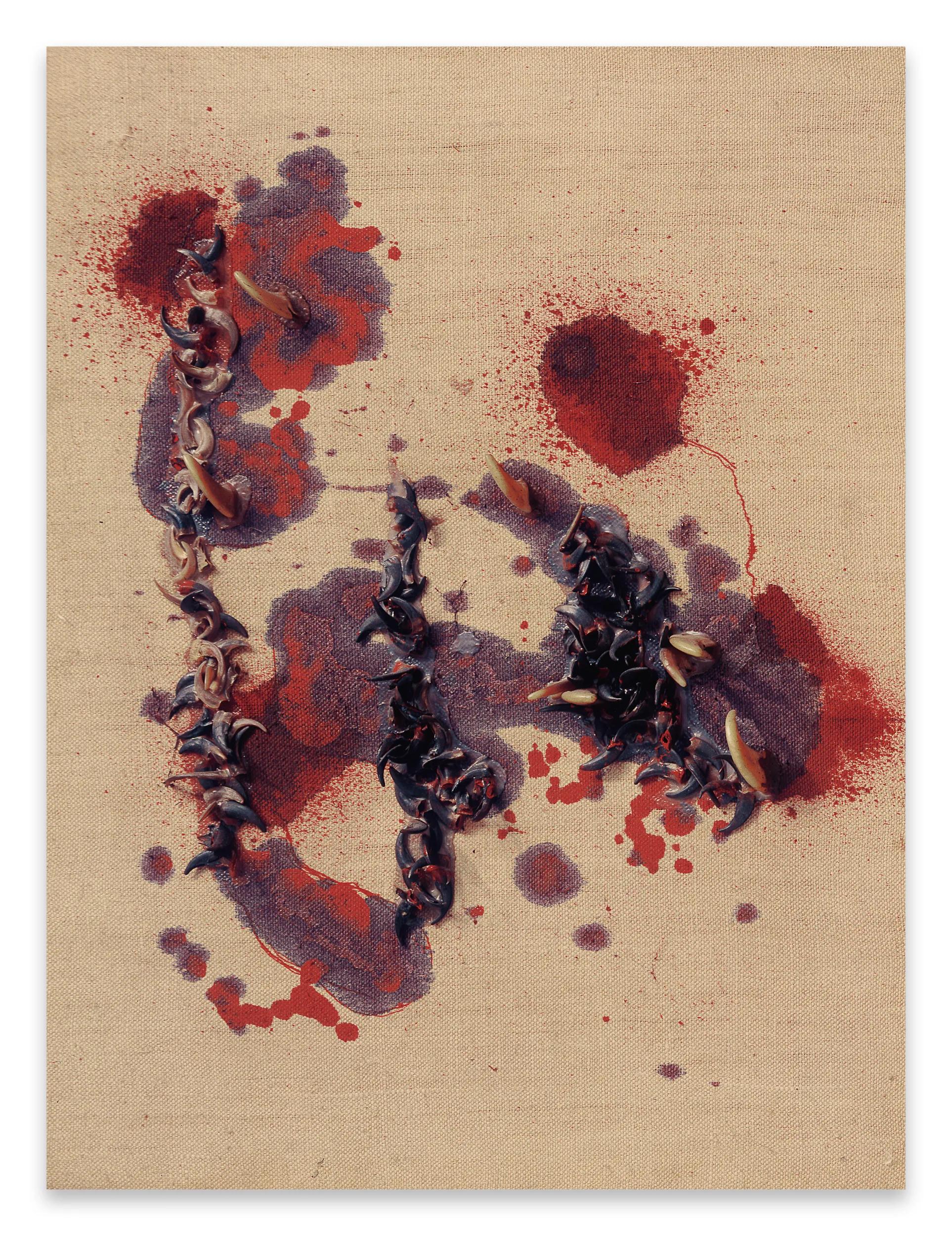

Carol Rama, La mucca pazza (The Mad Cow), 1998, Private Collection © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino. Photo: Pino Dell’Aquila

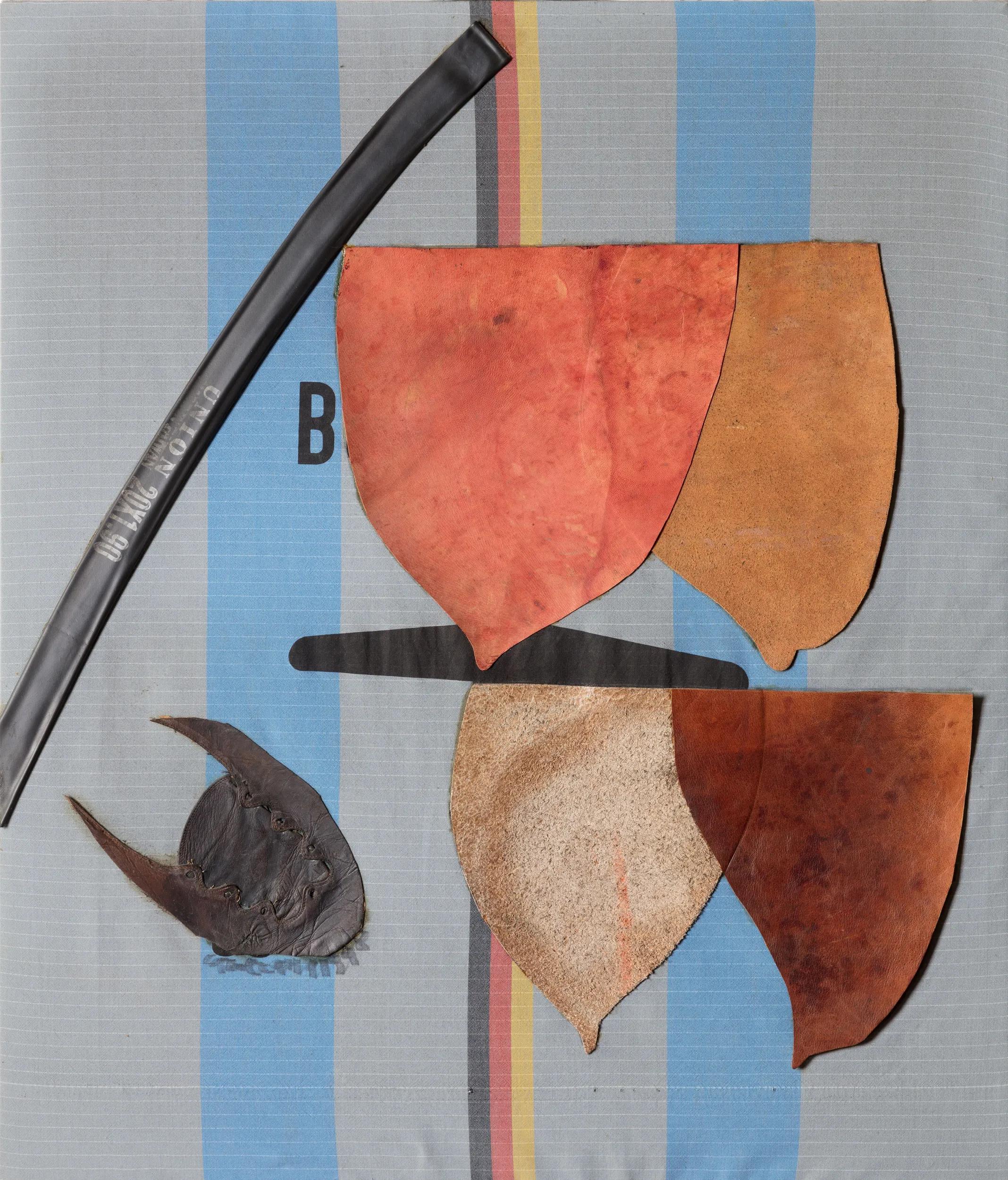

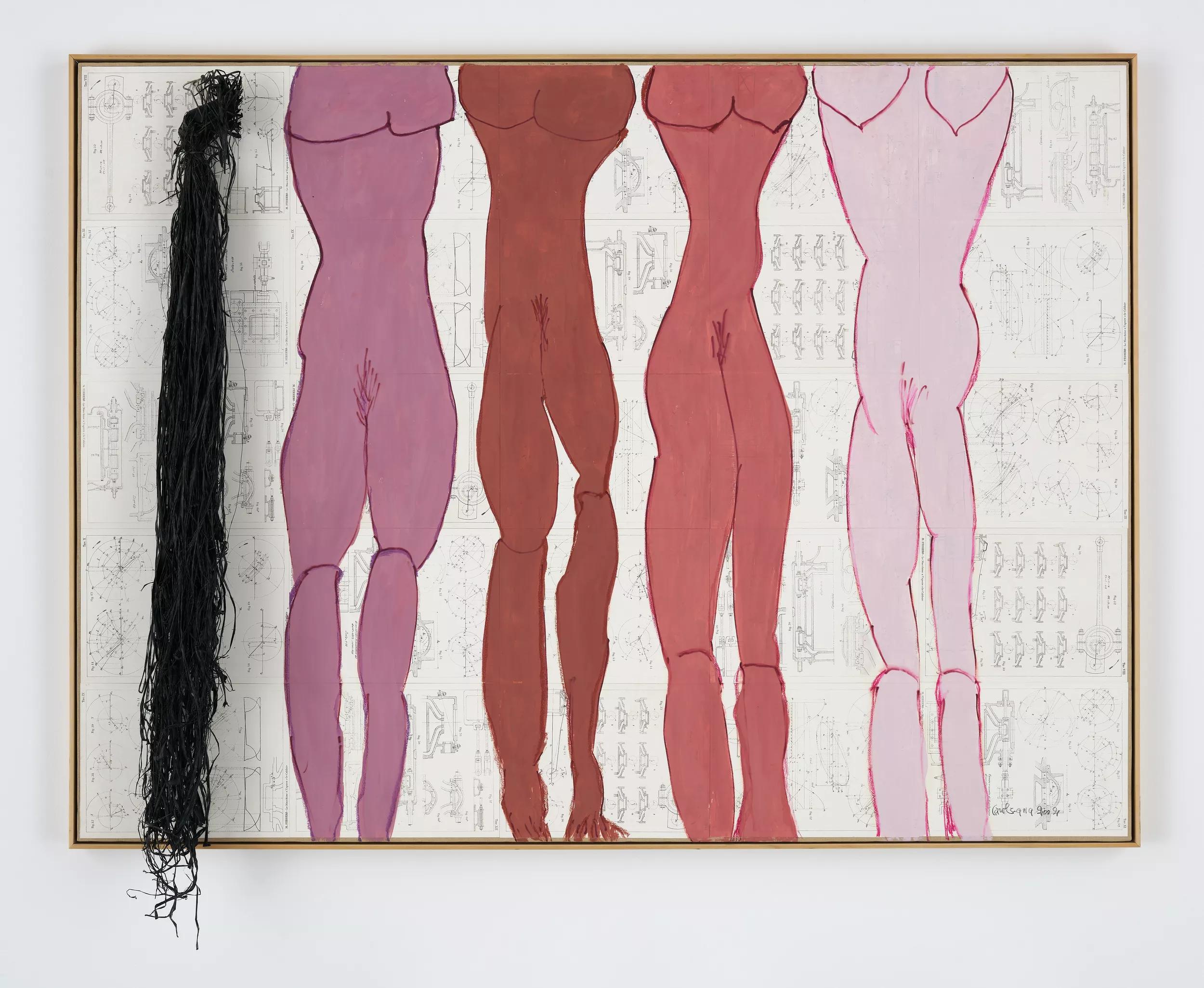

Carol Rama, Untitled, 1983, Private Collection © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino. Photo: Pino dell’Aquila

‘We are honored to welcome the Estate of Carol Rama to our gallery and collaborate closely with Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi to ensure that this extraordinary woman’s art is shared with new audiences around the world. Self-taught, fiercely independent and utterly untamed, Rama was a pioneer—she was unafraid to be as visceral and autobiographical as others were studied and protracted. Her legacy already is interwoven into the fabric of our gallery’s history through familial connection as we were first introduced to Carol’s art through my mother Ursula Hauser, a longtime champion. And we see such powerful connections between this artist’s concerns and those of other remarkable Hauser & Wirth artists, including Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Maria Lassnig and Lee Lozano who, like Carol, were underappreciated during their lifetimes and now are considered titans of art history. That so many of our younger gallery artists deeply admire Carol Rama is a sure signal that there will be very exciting dialogue and discovery ahead.’

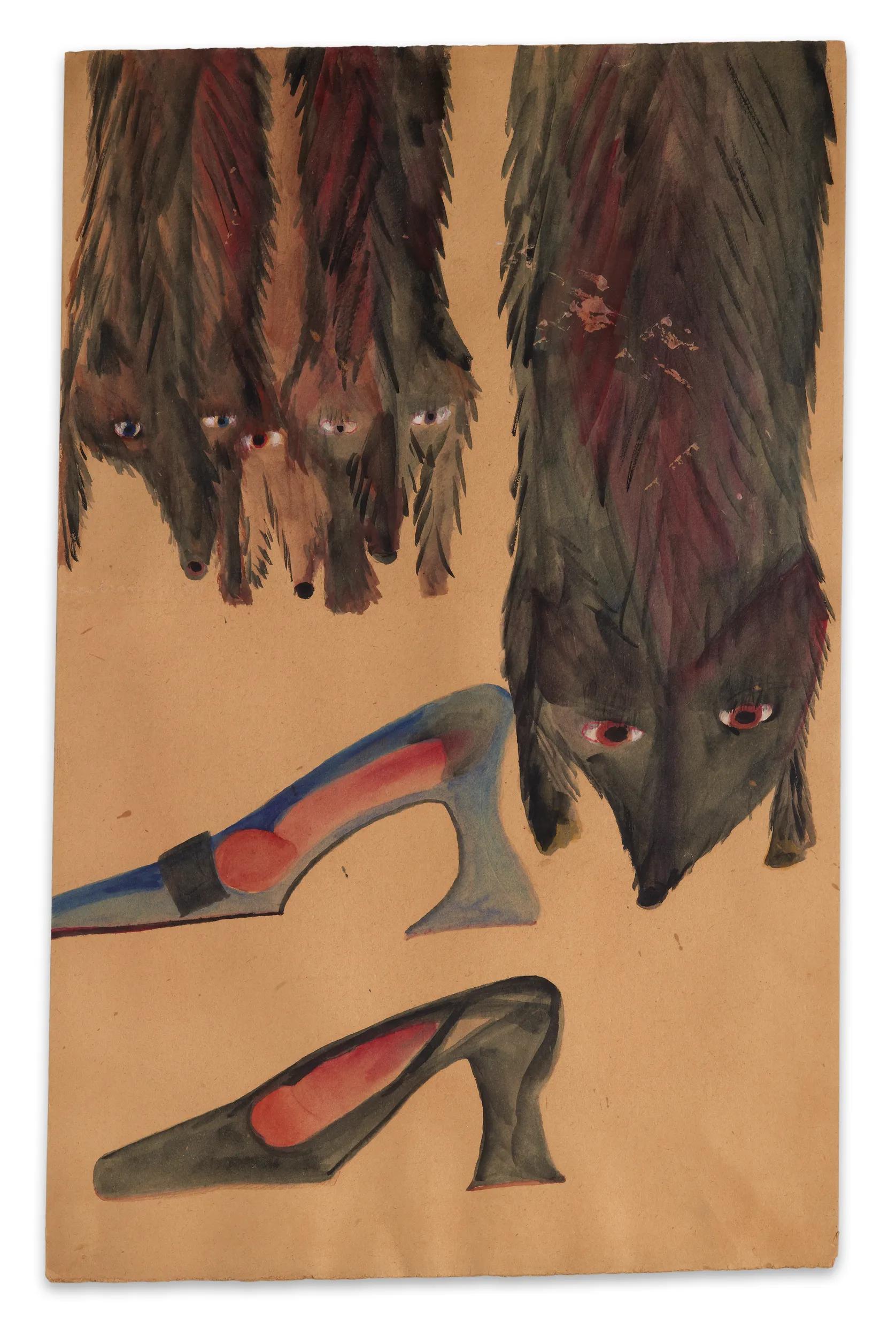

Carol Rama, Opera n. 11 (Work no. 11) (Renards), 1938, The Museum of Modern Art © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino. Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein

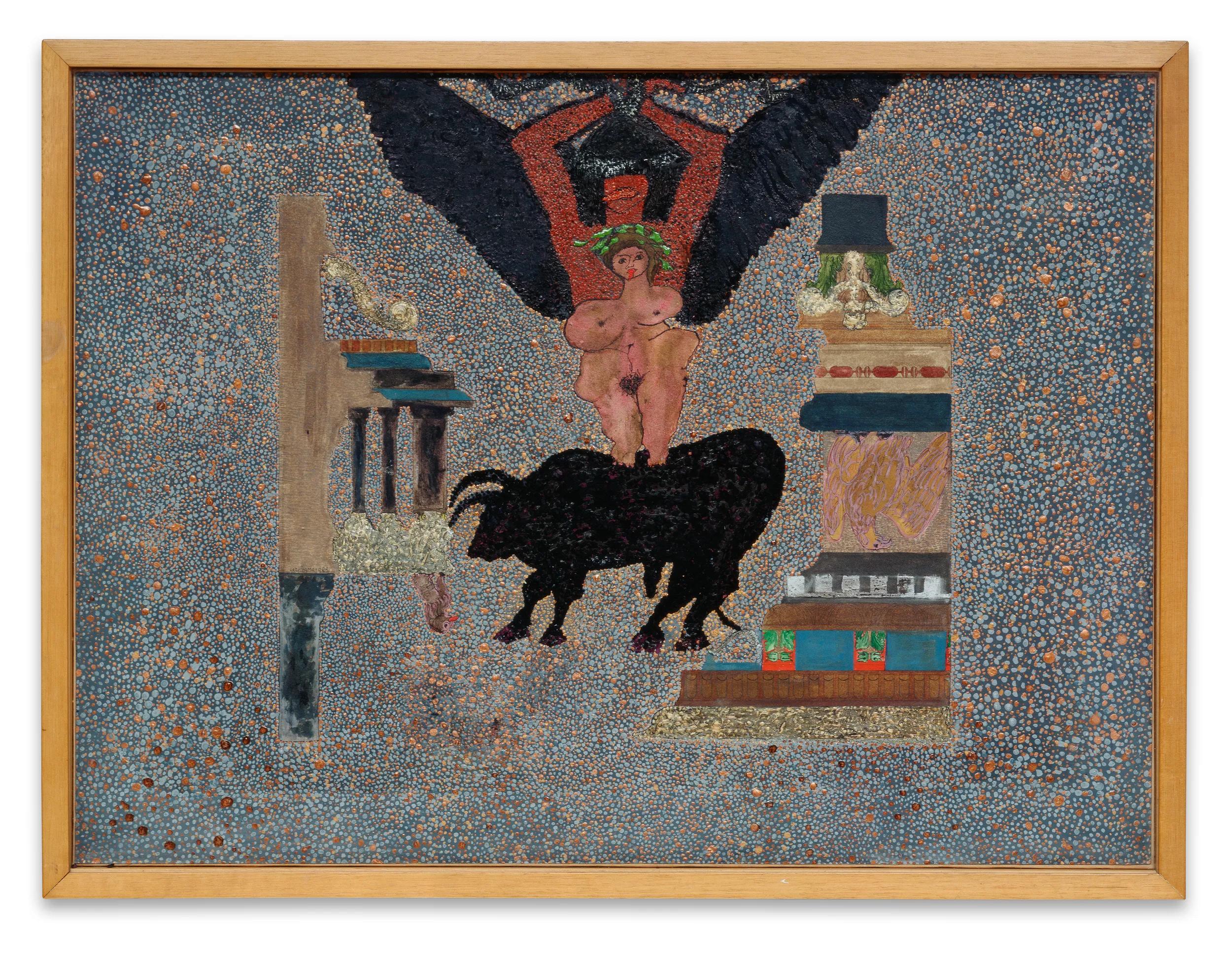

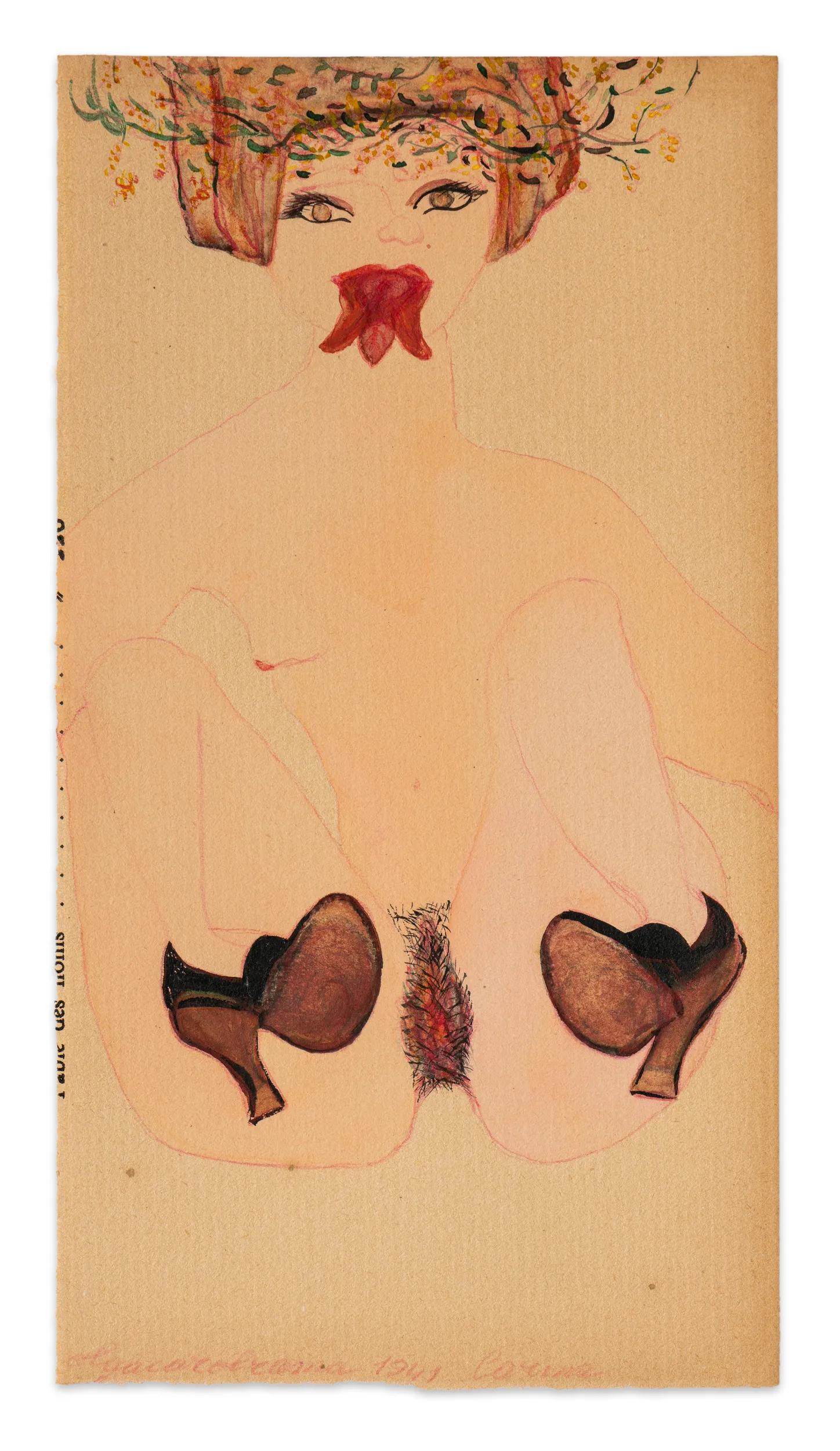

Carol Rama, Carina, 1941, Private Collection © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino. Photo: Pino Dell’Aquila

About the artist

Carol Rama was born in April 1918 in Turin, Italy, the youngest of three children, to parents Marta (née Pugliaro) and Amabile Rama, an automobile and bicycle entrepreneur. Initially prosperous, Amabile’s business is recalled in Rama’s art through references to factory life, its materials and components. From the late 1920s, an abrupt reversal of fortune and the subsequent demise of the family business led to Rama’s mother being admitted to a psychiatric hospital from December 1932 to April 1933, followed by Amabile’s death in 1942, likely by suicide. Rama’s observations during visits to her mother at the institution exerted a pivotal and liberating impact on the teenage artist, materializing through the psychosexual themes in her work. She later explained how these experiences replaced the formal training and classes she skipped at the art academy: ‘I felt comfortable in that surrounding. Because it’s there I began to have manners and upbringing without either cultural preparation or etiquette.’

The highly corporeal figurative watercolors that Rama created during the 1930s and 1940s, known as her ‘coarse drawings,’ formed the earliest chapter of her aesthetic emancipation. She conjured garlanded nudes whose limbless bodies, orifices, sharpened tongues and serpent phalluses are depicted within a world of restraints and orthopedic equipment, with such medical equipment frequently appearing as framing devices. The narratives of her Appassionata series and the squatting form of ‘Marta’ (1940) are as lascivious and defiant as they are grotesque and abject. These early works proved provocative enough to elicit censorship when, to Rama’s dismay, her 1945 debut exhibition at Opera pia Cucina Malati Poveri was shut down by police before it could open to the public due to the ‘obscenity’ of its contents.

Carol Rama, Untitled, 1966, Private Collection © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino. Photo: Gabriele Gaidano

Carol Rama, Untitled, 1963, Private Collection © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino. Photo: Tommaso Mattina

In the first of several significant aesthetic shifts during the course of her long career, Rama’s attention turned towards abstraction in the 1950s, with participation in Turin’s Concrete Art Movement and her pursuit of ‘a certain order’ and a self-imposed ‘limit to the excesses of freedom.’ As the decade progressed, Rama’s experimentation with new materials and intuitive ordering of fragmented forms were superseded by increasingly expressive painterly surfaces.

In the 1960s and 70s, Rama’s interest in found materials deepened. She developed an intellectual kinship with the Gruppo 63 poet Eduardo Sanguineti, one of the many writers, artists, architects and other members of the Italian avant-garde art milieu of which Rama was a part. Sanguineti applied the term ‘bricolage’ for works in which Rama forged an uncanny union between splattered paint resembling bodily secretions and artificial eyes, animal claws, teeth, electrical fuses and batteries. These elements are interspersed with obsessive notations and nonsensical equations in defiance of the rational and ordered systems of atomic warfare, which the artist viewed as ‘the ultimate lunacy.’

The early 1970s saw Rama’s visceral materiality combine with the autobiographical iconography of her father’s factory through collages and assemblages dangling with bicycle inner tubes like flaccid phalluses or intestines. Rama was drawn to this kind of found matter because, as she explained, ‘it gives you the idea it’s been used.’ Here, Rama’s work aligned with the spirit of the Arte Povera movement, although she was never a member of that group first identified by Germano Celant in 1969.

Carol Rama, Ostentazione (Ostentation), 2002 © Archivio Carol Rama, Torino. Ursula Hauser Collection, Switzerland. Photo: Jon Etter

The irrepressible figuration of Rama’s early watercolors finally gained international recognition in 1980 when curator Lea Vergine included them in her ambitious thematic exhibition ‘L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940’ (The Other Half of the Avant Garde 1910–1940), a survey that brought together works by over 100 women artists. Encouraged by the reception to her art in this show, Rama reprised the distinctive iconography she had developed in her youth, returning with renewed vigor to the body and her visual vocabulary of sharpened tongues, clusters of cocks and prosthetic limbs, rendering new mythical narratives featuring nude figures and animals. She layered such imagery over found technical drawings and architectural diagrams, which provided a structure to react to and push against.

This return to figuration and Rama’s lifelong embrace of the disordered mind as an expression of freedom collided in the final phase of her work, which lasted until her death in 2015 at the age of 97. Rama had become fascinated with the mad cow disease outbreak of the late 1990s and embraced it as the wellspring for a form of self-portraiture. She applied motifs of fractured body parts and udder-like fetish elements in leather to the surface of her work, declaring, ‘I believe there is no freedom without derangement. But then we are all pretty deranged.’

Selected prominent museum collections which have holdings of Rama’s work include The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago IL; Centre Pompidou, Paris, France; Collezione Intesa Sanpaolo, Milano, Italy; Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Bologna, Italy; GAM - Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin, Italy; MACBA, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; MAM, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, Paris, France; MART, Rovereto, Italy; MEF Museo Ettore Fico, Turin, Italy; MoMA, The Museum of Modern Art, New York NY; Museo del Novecento, Milan, Italy; Sammlung Goetz, Munich, Germany; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Tate, London, UK; and Uffizi, Florence, Italy.

Related News

1 / 5