Oudolf Field

Photo: Jason Ingram

Oudolf Field

What makes it doubly special is the conditions of its birth. If ever there were a difficult year to create a garden from nothing more than a bare field surrounded by hedges, it was 2014. Months of relentless rain in the wettest winter on record reduced the soil to a quagmire, followed by weeks of drought, just when the 26,000 plants grown at Orchard Dene nursery in Oxfordshire were getting established. But, despite all this – and thanks also to the glorious late summer and the hard work of Petherick, Urquhart & Hunt, the landscapers, as well as Mark Dumbleton, Durslade’s head gardener – the team has pulled off one of the most exciting new gardens in the country.

Piet, who hails from Holland, is one of the world’s most revered landscape designers and Iwan Wirth was already a fan of what is arguably his most famous work - the planting on the High Line in lower Manhattan (which passes by Hauser & Wirth’s new gallery on West 18th Street) - but it was another enclosed garden that brought the two together, when Piet designed the ‘hortus conclusus’ at the centre of Peter Zumthor’s 2011 pavilion for the Serpentine Gallery in Kensington Gardens, London. ‘One of the directors, Hans Ulrich Obrist, called Iwan and said, ‘I think you need someone for your garden: I have him’,’ says Piet.

As to what Iwan had in mind for the gallery landscaping, it couldn’t have been simpler: ‘The brief was absolute freedom, with no compromise,’ says Piet. ‘He wanted me to feel free in what I did; I think that is what he wants to do with his artists, too.’ That’s a brief most designers could live with, but what also appealed was that the garden would be included as an integral part of the larger vision of the building complex. ‘It would work by itself, but I think it gets more sense of place when it is set in a wider context. In the gallery, there is beauty everywhere; then you come into the garden, which is part of the whole idea of everything that happens there.’

Photo: Alex Delfanne

Within the interior cloister of the gallery, Piet created a scheme of vivid green Sesleria autumnalis and other grasses, dotted with dark perennials, such as Cimifuga brunette, Gilenia trifoliate and Astrantia ‘Venice’, keeping things low and simple, so they don’t detract from the sculptures that shares the space. But, once you get to the back of the gallery and stand in the modernist colonnade, looking towards the gentle upward slope, it is his own work that takes centre stage. Wide paths lead you past a pond area planted with the likes of Iris siberica ‘Perry’s Blue’, muscular Darmara peltata and the striking red Lobelia tupa, which is cleverly hidden from view until you are in the garden itself, then the scheme opens out into great drifts of purples, pinks, blues, rust and gold, as well as meadows of airy sporobolus grass, dotted with perennials.

At the corners of the garden is more robust planting of tall growers such as Molina ‘Transparent’, filipendula and cimifiguga. Seen as whole – which is what Piet intends – it looks like a giant artist’s palette. Even on a busy Sunday afternoon, when you are standing among the plants, looking back towards the gallery and Bruton’s iconic dovecote beyond, with the bees humming and butterflies fluttering around you, there is a real sense of calm, as if you have the garden all to yourself.

Photo: Jason Ingram

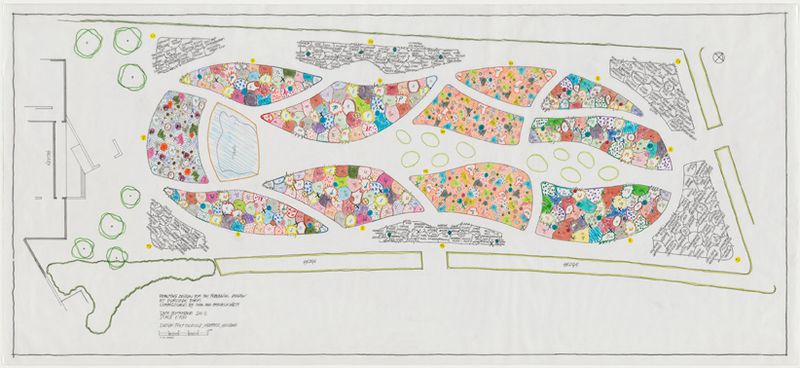

The garden has been the inspiration for a series of talks at the gallery on Art of the Garden, featuring many of the leading lights in garden design today. The first one, fittingly, was with Piet himself and his plan for Durslade were also shown as one of the gallery’s opening exhibitions. These hand-drawn patchworks of colour and shading look like pieces of artwork themselves: whereas some designers imagine a landscape as a piece of music, with allegros and adagios, and others draw it all out in graphic style on CAD, Piet sees the finished thing as a picture in his mind’s eye from the beginning. He then considers which plants will fulfil this vision and builds it up in sketches, layer by layer.

It helps that, with all his years as a plantsman and nursery owner, Piet has a deep knowledge of plants, their habits and how they will work with the others around them. ‘You know what plants will do over time, and what will flower when.’ He’s careful not to use varieties that will become too thuggish, or self-seed all over the place, spoiling the equilibrium of the picture. ‘The plants will grow, but you use varieties that will stay put, more or less. They will grow bigger but not take over.’ Once he’s worked out he wants a clump of Aster macryphyllus ‘Twilight’ here, a ribbon of Monarda bradburiana there, and he’s committed it all to paper, down to the exact number of plants for each spot, he sticks to his scheme. ‘I don’t fiddle, which is what a lot of people do.’

Photo: Jason Ingram

Piet’s gardens are most famous for their drifts and blocks of rich late-summer colour, and the strong forms of the stems and seedheads that provide a wintry canvas to look out on until they are cut back in February. But he hasn’t forgotten about the early part of the season at Durslade. Mark has been busy planting thousands of bulbs, such as Allium nigra, irises and little botanical tulips, which will emerge among the fresh green forms of the young plants waking up from their winter slumbers. ‘There will always be lots of energy there,’ says Piet.

Designing for a public space rather than a private garden brings its own considerations. ‘Sometimes you need bodyguards to protect the garden from the public,’ jokes Piet, who has had to change grass to gravel on some of the paths, such has been the numbers of visitors coming to the garden, especially after 6it was so highly praised by Monty Don on the BBC’s Gardeners’ World in September 2014. ‘They sneak through this, they step on that, they want to take a picture with one foot in the planting. You’ve got children running through, playing hide and seek: you have to keep all this in mind. If you garden like you do at home, it doesn’t work; your plants have to be stronger and bolder, and not too fine - so, if you lose one, you aren’t crying.’ So what is Piet’s own vision for the space? ‘That people will hang around; they won’t just want to come to the gallery, they also want to be in the garden.’ With Durslade firmly on the map of exciting gardens to visit, it would seem his wishes have come true.

Related News

1 / 5